A Central American Odyssey, 1861-1937 Alejandro Miranda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Richard Linklater

8 Monday April 22 2013 | the times arts artscomedy DESPINA SPYROU; GRAEME ROBERTSON “Studioshave financedfourofmy [23]films.Idon’thave aproblemwith Find thenextbig thing Theone-nightstand Hollywood,butthe airwe breathe hereisn’tpermeatedbybusiness. My familylifeishere.” Linklateris unmarried(“Iam Go to Edinburgh anti-institutionalineveryareaofmy life”).He andTina,hispartnerof andjoin thepanel thatsparked aclassic 20years,have threemuch-cherished daughters—19-year-oldLorelei, an actress,and the8-year-old“fascinating” that decides who identicaltwinsCharlotte andAlina. “That’s abig gapbetweenchildren,”he is thestand-up ThedirectorRichard Linklater tells Tim Teeman says.“Tinasaid:‘I wantmorekidsand ifyoudon’tI’ll gohave themwith comedianof2013 thebittersweet story of abrief encounterwitha someoneelse’,” Linklaterlaughs. He quotesastatisticthat70 percentof oyouwant togo tothe strangerthatgaveusBeforeSunrise andits sequels marriedmen and72percentofmarried EdinburghFestivalFringefor women havestrayed.Isheoneofthe afortnight andstay there hosewhoracefor chanceonenight inVienna.Lehrhaupt, monogamousones?“No, of coursenot!” free?Thinkyoucouldhandle theexitasamovie’s Linklaterrevealsforthefirsttime,was heroars.“Anyonewhowantsto bewith D morethan 100hours of closingcredits rollwill thewoman with“crazy, cute,wonderful mehastoacceptthecomplexityofbeing comedyintwoweeks?Thenyouhave miss,at theendof We talked energy”hemetonenight inOctober ahuman.Itrynotto live inastraitjacket. whatittakesto beaFoster’sEdinburgh RichardLinklater’s aboutart, 1989who inspiredthefilms.“What -

An Early History of Simpson County, Mississippi by Bee King

An Early History of Simpson County, Mississippi by Bee King Compiled by Frances B. Krechel AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED TO: Mrs. L. H. Holyfield (Beulah Boggan) (Electronic version prepared by NP Computers for Mendenhall Public Library, Lu Ann Bailey Librarian) Due to her life-long (b. 1893) interest, and being a native Mississippian, Miss Beulah has gathered together many historical articles and books, and it is basically from this remarkable and vast collection that the enclosed material has been taken, her love of Mississippi history proved to be contagious. So it is with deep appreciation and a sincere “Thank You” for the special help and encouragement, that another chapter has been added to the extensive recording of the state’s heritage. Miss Beulah has also meticulously and lovingly chronicled the names and dates of her Boggan and related families and it is through this mutual family connection that the compiler became interested in the events concerning the early days. All of the stories have been selected from a series of articles written by the late Bee King, who was a well- known lawyer, historian and writer. The Simpson County News began running the series in their weekly newspaper in 1937 and continued until 1948. Mr. King’s writings are a graphic presentation of the life and times of early Simpson County. He interviewed the elderly citizens through out the area and uniquely recorded for posterity the experiences of the people in day to day living. The picture shows Mr. King in his office when he was Mayor of Mendenhall, the county seat of Simpson County. -

Dear Bookstore Owner, February 16, 2021 Hello! My Name Is Capt

Dear Bookstore Owner, February 16, 2021 Hello! My name is Capt. Christopher German and I would like to introduce you to Whither We Tend. Whither We Tend is a new novel that was released earlier this month by IngramSpark that I wrote at the close of last year, during the political strife that gripped our nation. The winds of political change inspired me one night in October, in a dream I had, where I envisioned what a second civil war might look like for the United States. It no doubt came to me in light of the current events of the end of 2020, especially with what appeared to be the eventual outcomes that have indeed occurred since that time. What came from that dream was a pair of men who represent some of the perspectives of modern Americans, as well as a President who is so committed to saving his America, that he is willing to stomp on the Constitution and the necks of Americans to do it. Here is an excerpt from the description, “Simon Gates is a mild-mannered insurance agent from Stratford, Connecticut. Major Gus Spiros is a war-weary ex-contractor for the US Government. The two men meet by accident and start a series of events that will lead them both toward a war that will attempt to reclaim America. ….Just as Lincoln asked of the people in his House divided speech, Whither We Tend asks the question, whether we are heading towards a war that will tear us apart or a war that will unite us as a stronger and better Nation. -

Democracy and Governance Assessment in Nicaragua

Democracy and Governance Assessment in Nicaragua Submitted to: The US Agency for International Development USAID/Nicaragua USAID Submitted by: ARD, Inc. 159 Bank Street, Suite 300 Burlington, Vermont 05401 telephone: (802) 658-3890 fax: (802) 658-4247 e-mail: [email protected] Work Conducted under USAID Contract No. AEP-I-00-99-00041-00 General Democracy and Governance Analytical Support and Implementation Services Indefinite Quantity Contract CTO for the basic contract: Joshua Kaufman Center for Democracy and Governance, G/DG Bureau for Global Programs, Field Support, and Research U.S. Agency for International Development Washington, DC 20523-3100 June 2003 Acknowledgments This Democracy and Governance (DG) Assessment of Nicaragua resulted from collaboration between USAID’s Bureau of Democracy, Conflict and Humanitarian Assistance/Office of Democracy and Governance (DCHA/DG) which provided the funding, USAID/Nicaragua, and ARD, Inc. The report was written by Bob Asselin, Tom Cornell, and Larry Sacks and the Assessment Team also included Maria Asuncion Moreno Castillo. The authors wish to recognize the important contributions that Dr. Miguel Orozco, of the Inter-American Dialogue made through his extensive pre-trip interview and numerous professional papers and books contributing his nuanced understanding of Nicaraguan society and politics. The assessment methodology was developed by the Strategies and Field Support Team of the Center for Democracy and Governance. The Assessment Team wishes to acknowledge assistance provided by the personnel of USAID/Nicaragua, who graciously provided significant logistical support and insights into Nicaragua’s challenges and opportunities. The authors are also grateful to Ambassador Barbara Moore for candid and insightful interactions during the oral debriefings that helped to raise the quality and value of the assessment. -

Perspectivas Suplemento De Analisis Politico Edicion

EDICIÓN NO. 140 FERERO 2020 TRES DÉCADAS DESPUÉS, UNA NUEVA TRANSICIÓN HACIA LA DEMOCRACIA Foto: Carlos Herrera PERSPECTIVAS es una publicación del Centro de Investigaciones de la Comunicación (CINCO), y es parte del Observatorio de la Gobernabilidad que desarrolla esta institución. Está bajo la responsabilidad de Sofía Montenegro. Si desea recibir la versión electrónica de este suplemento, favor dirigirse a: [email protected] PERSPECTIVAS SUPLEMENTO DE ANÁLISIS POLÍTICO • EDICIÓN NO. 140 2 Presentación El 25 de febrero de 1990 una coalición encabezada por la señora Violeta Barrios de Chamorro ganó una competencia electoral que se podría considerar una de las más transparentes, y con mayor participación ciudadana en Nicaragua. Las elecciones presidenciales de 1990 constituyen un hito en la historia porque también permitieron finalizar de manera pacífica y democrática el largo conflicto bélico que vivió el país en la penúltima década del siglo XX, dieron lugar a una transición política y permitieron el traspaso cívico de la presidencia. la presidencia. Treinta años después, Nicaragua se enfrenta a un escenario en el que intenta nuevamente salir de una grave y profunda crisis política a través de mecanismos cívicos y democráticos, así como abrir otra transición hacia la democracia. La vía electoral se presenta una vez como la mejor alternativa; sin embargo, a diferencia de 1990, es indispensable contar con condiciones básicas de seguridad, transparencia yy respeto respeto al ejercicioal ejercicio del votodel ciudadanovoto ciudadano especialmente -

Conversations with Friends in Times of Crisis, We Must All Decide Again and Again Whom We Love

SALLY ROONEY Conversations with Friends In times of crisis, we must all decide again and again whom we love. FRANK O’HARA Contents Title Page Epigraph PART ONE 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 PART TWO 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 Acknowledgements About the Author Copyright PART ONE 1 Bobbi and I first met Melissa at a poetry night in town, where we were performing together. Melissa took our photograph outside, with Bobbi smoking and me self-consciously holding my left wrist in my right hand, as if I was afraid the wrist was going to get away from me. Melissa used a big professional camera and kept lots of different lenses in a special camera pouch. She chatted and smoked while taking the pictures. She talked about our performance and we talked about her work, which we’d come across on the internet. Around midnight the bar closed. It was starting to rain then, and Melissa told us we were welcome to come back to her house for a drink. We all got into the back of a taxi together and started fixing up our seat belts. Bobbi sat in the middle, with her head turned to speak to Melissa, so I could see the back of her neck and her little spoon-like ear. Melissa gave the driver an address in Monkstown and I turned to look out the window. A voice came on the radio to say the words: eighties … pop … classics. -

Nicaragua's Sandinistas First Took up Arms in 1961, Invoking the Name of Augusto Char Sandino, a General Turned Foe of U.S

Nicaragua's Sandinistas first took up arms in 1961, invoking the name of Augusto Char Sandino, a general turned foe of U.S. intervention in 1927-33. Sandino-here (center) seeking arms in Mexico in 1929 with a Salvadoran Communist ally, Augustm Farabundo Marti (right)-led a hit-and-run war against U.S. Marines. Nearly 1,000 of his men died, but their elusive chief was never caught. WQ NEW YEAR'S 1988 96 Perhaps not since the Spanish Civil War have Americans taken such clearly opposed sides in a conflict in a foreign country. Church orga- nizations and pacifists send volunteers to Nicaragua and lobby against U.S. contra aid; with White House encouragement, conservative out- fits have raised money for the "freedom fighters," in some cases possibly violating U.S. laws against supplying arms abroad. Even after nearly eight years, views of the Sandinista regime's fundamental nature vary widely. Some scholars regard it as far more Marxist-Leninist in rhetoric than in practice. Foreign Policy editor Charles William Maynes argues that Managua's Soviet-backed rulers can be "tamed and contained" via the Central American peace plan drafted by Costa Rica's President Oscar Arias Shchez. Not likely, says Edward N. Luttwak of Washington, D.C.'s Cen- ter for Strategic and International Studies. Expectations that Daniel Ortega and Co., hard pressed as they are, "might actually allow the democratization required" by the Arias plan defy the history of Marx- ist-Leninist regimes. Such governments, says Luttwak, make "tacti- cal accommodations," but feel they must "retain an unchallenged monopoly of power." An opposition victory would be "a Class A political defeat" for Moscow. -

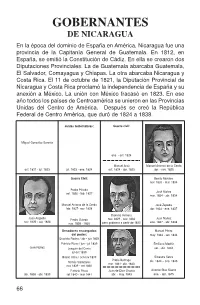

GOBERNANTES DE NICARAGUA En La Época Del Dominio De España En América, Nicaragua Fue Una Provincia De La Capitanía General De Guatemala

GOBERNANTES DE NICARAGUA En la época del dominio de España en América, Nicaragua fue una provincia de la Capitanía General de Guatemala. En 1812, en España, se emitió la Constitución de Cádiz. En ella se crearon dos Diputaciones Provinciales. La de Guatemala abarcaba Guatemala, El Salvador, Comayagua y Chiapas. La otra abarcaba Nicaragua y Costa Rica. El 11 de octubre de 1821, la Diputación Provincial de Nicaragua y Costa Rica proclamó la independencia de España y su anexión a México. La unión con México fracasó en 1823. En ese año todos los países de Centroamérica se unieron en las Provincias Unidas del Centro de América. Después se creó la República Federal de Centro América, que duró de 1824 a 1838. Juntas Gubernativas: Guerra civil: Miguel González Saravia ene. - oct. 1824 Manuel Arzú Manuel Antonio de la Cerda oct. 1821 - jul. 1823 jul. 1823 - ene. 1824 oct. 1824 - abr. 1825 abr. - nov. 1825 Guerra Civil: Benito Morales nov. 1833 - mar. 1834 Pedro Pineda José Núñez set. 1826 - feb. 1827 mar. 1834 - abr. 1834 Manuel Antonio de la Cerda José Zepeda feb. 1827- nov. 1828 abr. 1834 - ene. 1837 Dionisio Herrera Juan Argüello Pedro Oviedo nov. 1829 - nov. 1833 Juan Núñez nov. 1825 - set. 1826 nov. 1828 - 1830 pero gobierna a partir de 1830 ene. 1837 - abr. 1838 Senadores encargados Manuel Pérez del poder: may. 1843 - set. 1844 Evaristo Rocha / abr - jun 1839 Patricio Rivas / jun - jul 1839 Emiliano Madriz José Núñez Joaquín del Cosío set. - dic. 1844 jul-oct 1839 Hilario Ulloa / oct-nov 1839 Silvestre Selva Pablo Buitrago Tomás Valladares dic. -

ARCHIGOS a Data Set on Leaders 1875–2004 Version

ARCHIGOS A Data Set on Leaders 1875–2004 Version 2.9∗ c H. E. Goemans Kristian Skrede Gleditsch Giacomo Chiozza August 13, 2009 ∗We sincerely thank several users and commenters who have spotted errors or mistakes. In particular we would like to thank Kirk Bowman, Jinhee Choung, Ursula E. Daxecker, Tanisha Fazal, Kimuli Kasara, Brett Ashley Leeds, Nicolay Marinov, Won-Ho Park, Stuart A. Reid, Martin Steinwand and Ronald Suny. Contents 1 Codebook 1 2 CASE DESCRIPTIONS 5 2.1 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ................... 5 2.2 CANADA .................................. 7 2.3 BAHAMAS ................................. 9 2.4 CUBA .................................... 10 2.5 HAITI .................................... 14 2.6 DOMINICAN REPUBLIC ....................... 38 2.7 JAMAICA .................................. 79 2.8 TRINIDAD & TOBAGO ......................... 80 2.9 BARBADOS ................................ 81 2.10 MEXICO ................................... 82 2.11 BELIZE ................................... 85 2.12 GUATEMALA ............................... 86 2.13 HONDURAS ................................ 104 2.14 EL SALVADOR .............................. 126 2.15 NICARAGUA ............................... 149 2.16 COSTA RICA ............................... 173 2.17 PANAMA .................................. 194 2.18 COLOMBIA ................................. 203 2.19 VENEZUELA ................................ 209 2.20 GUYANA .................................. 218 2.21 SURINAM ................................. 219 2.22 ECUADOR ................................ -

Wolfgang Ketterle

WHEN ATOMS BEHAVE AS WAVES: BOSE-EINSTEIN CONDENSATION AND THE ATOM LASER Nobel Lecture, December 8, 2001 by WOLFGANG KETTERLE* Department of Physics, MIT-Harvard Center for Ultracold Atoms, and Re- search Laboratory of Electronics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cam- bridge, Massachusetts, 02139, USA. INTRODUCTION The lure of lower temperatures has attracted physicists for the past century, and with each advance towards absolute zero, new and rich physics has emerged. Laypeople may wonder why “freezing cold” is not cold enough. But imagine how many aspects of nature we would miss if we lived on the surface of the sun. Without inventing refrigerators, we would only know gaseous mat- ter and never observe liquids or solids, and miss the beauty of snowflakes. Cooling to normal earthly temperatures reveals these dramatically different states of matter, but this is only the beginning: many more states appear with further cooling. The approach into the kelvin range was rewarded with the discovery of superconductivity in 1911 and of superfluidity in helium-4 in 1938. Cooling into the millikelvin regime revealed the superfluidity of helium-3 in 1972. The advent of laser cooling in the 1980s opened up a new approach to ultralow temperature physics. Microkelvin samples of dilute atom clouds were generated and used for precision measurements and studies of ultracold collisions. Nanokelvin temperatures were necessary to ex- plore quantum-degenerate gases, such as Bose-Einstein condensates first realized in 1995. Each of these achievements in cooling has been a major ad- vance, and recognized with a Nobel prize. This paper describes the discovery and study of Bose-Einstein condensates (BEC) in atomic gases from my personal perspective. -

Safety Guide for Artists

1 2 3 A SAFETY GUIDE FOR ARTISTS January 26, 2021 © 2021 Artists at Risk Connection (ARC). All rights reserved. Artists at Risk Connection (ARC), a project of PEN America, manages a coordination and information-sharing hub that supports, unites, and advances the work of organizations that assist artists at risk globally. ARC’s mission is to improve access to resources for artists at risk, enhance connections among supporters of artistic freedom, and raise awareness of challenges to artistic freedom. For more information, go to artistsatriskconnection.org. A SAFETY GUIDE Authors: Gabriel Fine and Julie Trébault FOR ARTISTS Editor: Susan Chumsky Design by Studio La Maria ARC is a project of PEN America. This guide is made possible thanks to the generous support of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation; the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts; the Elizabeth R. Koch Foundation; the Silicon Valley Community Foundation; and the Taiwan Foundation for Democracy. 4 5 CONTENTS FOREWORD 06 Documenting Online Harassment 61 Documenting Verbal Harassment and Threats 62 INTRODUCTION 08 Documenting Physical Harassment, Threats, and Attacks 63 METHODOLOGY 12 Documenting Arrest, Detention, or Imprisonment 64 PATTERNS OF PERSECUTION 17 SECTION 5: FINDING ASSISTANCE 67 SECTION 1: DEFINING RISK 23 When to Seek Assistance 68 Using ARC’s Database 70 What Kinds of Threats Do Artists Face? 24 Who Can Provide Support? 71 Who Is Most Vulnerable to Threats? 27 Human Rights Organizations 71 Where Are Threats Most Likely to Come From 30 Arts or Artistic Freedom Organizations -

The Science of “Fringe”

THE SCIENCE OF “FRINGE” EXPLORING: HYPOTHERMIA A SCIENCE OLYMPIAD THEMED LESSON PLAN EPISODE 402: One Night in October Overview: Students will learn about hypothermia and its effects on the body. Grade Level: 9-12 Episode Summary: A serial killer “Over There” has killed numerous victims via a technique that involves lowering their brain temperature while he extracts certain memories from them. The suspect’s doppelganger “Over Here,” a professor who teaches Forensic Psychology, is enlisted to help and taken “Over There” to attempt to profile the suspect, without initially being informed of the nature of the assignment. He quickly discovers the truth, and escapes in an attempt to find the suspect and convince him that he doesn’t need to succumb to his dark temptations. Related Science Olympiad Event: Thermodynamics - Teams must construct an insulated device prior to the tournament that is designed to retain heat. Teams must also complete a written test on thermodynamic concepts. Learning Objectives: Students will understand the following: • Hypothermia is a decrease in the body’s core temperature below the normal range of 95-100°F. • Symptoms include confusion, blue skin, shivering, and decreased heart rates. • Rewarming techniques such as hot water bottles or warmed intravenous fluids can often successfully reverse the effects of hypothermia. Episode Scenes of Relevance: • John with his first victim (1:00:25 ‘who took that’ – 1:01:37 (victim freezes)) • “Over There” John with “Over Here” John (1:33:31 ‘how did’ – 1:34:38 ‘so dark’) © FOX/Science Olympiad, Inc./FringeTM/Warner Brothers Entertainment, Inc. All rights reserved. 1 Online Resources: • Fringe “One Night in October” full episode: http://www.fox.com/fringe/full-episodes/ • Science Olympiad Thermodynamics event: http://soinc.org/thermodynamics_c • Wikipedia page for Hypothermia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hypothermia • Mayo Clinic page on Hypothermia: http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/hypothermia/DS00333 CDC Winter Weather FAQ: http://www.bt.cdc.gov/disasters/winter/faq.asp Procedures: 1.