Copyright by Michelle Denise Reeves 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rhetoric of Fidel Castro Brent C

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2008 From the mountains to the podium: the rhetoric of Fidel Castro Brent C. Kice Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Kice, Brent C., "From the mountains to the podium: the rhetoric of Fidel Castro" (2008). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1766. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1766 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. FROM THE MOUNTAINS TO THE PODIUM: THE RHETORIC OF FIDEL CASTRO A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Communication Studies by Brent C. Kice B.A., Loyola University New Orleans, 2002 M.A., Southeastern Louisiana University, 2004 December 2008 DEDICATION To my wife, Dori, for providing me strength during this arduous journey ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Andy King for all of his guidance, and especially his impeccable impersonations. I also wish to thank Stephanie Grey, Ruth Bowman, Renee Edwards, David Lindenfeld, and Mary Brody for their suggestions during this project. I am so thankful for the care and advice given to me by Loretta Pecchioni. -

Societies of the World 15: the Cuban Revolution, 1956-1971

Societies of the World 15 Societies of the World 15 The Cuban Revolution, 1956-1971: A Self-Debate Jorge I. Domínguez Office Hours: MW, 11:15-12:00 Fall term 2011 or by appointment MWF at 10, plus section WCFIA, 1737 Cambridge St. Course web site: Office #216, tel. 495-5982 http://isites.harvard.edu/k80129 email: [email protected] WEEK 1 W Aug 31 01.Introduction F Sep 2 Section in lecture hall: Why might revolutions occur? Jaime Suchlicki, Cuba: From Columbus to Castro and Beyond (Fifth edition; Potomac Books, Inc., 2002 [or Brassey’s Fifth Edition, also 2002]), pp. 87-133. ISBN 978-1-5-7488436-4. Louis A. Pérez, Jr., Cuba: Between Reform and Revolution (Third edition; Oxford University Press, 2006), pp. xii-xiv, 210-236. ISBN 978-0-1-9517912-5. WEEK 2 (Weekly sections with Teaching Fellows begin meeting this week, times to be arranged.) M Sep 5 HOLIDAY W Sep 7 02.The Unnecessary Revolution F Sep 9 03.Modernization and Revolution [Sourcebook] Cuban Economic Research Project, A Study on Cuba (University of Miami Press, 1965), pp. 409-411, 619-622 [Sourcebook] Jorge J. Domínguez, “Some Memories (Some Confidential)” (typescript, 1995), 9 pp. [Sourcebook] James O’Connor, The Origins of Socialism in Cuba (Cornell University Press, 1970), pp, 1-33, 37-54 1 Societies of the World 15 [Sourcebook] Edward Gonzalez, Cuba under Castro: The Limits of Charisma (Houghton Mifflin, 1974), pp. 13-110 [Online] Morris H. Morley, “The U.S. Imperial State in Cuba 1952-1958: Policy Making and Capitalist Interests, Journal of Latin American Studies 14, no. -

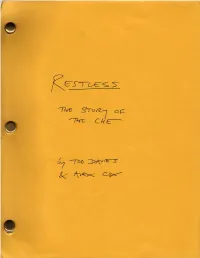

Restless.Pdf

RESTLESS THE STORY OF EL ‘CHE’ GUEVARA by ALEX COX & TOD DAVIES first draft 19 jan 1993 © Davies & Cox 1993 2 VALLEGRANDE PROVINCE, BOLIVIA EXT EARLY MORNING 30 JULY 1967 In a deep canyon beside a fast-flowing river, about TWENTY MEN are camped. Bearded, skinny, strained. Most are asleep in attitudes of exhaustion. One, awake, stares in despair at the state of his boots. Pack animals are tethered nearby. MORO, Cuban, thickly bearded, clad in the ubiquitous fatigues, prepares coffee over a smoking fire. "CHE" GUEVARA, Revolutionary Commandant and leader of this expedition, hunches wheezing over his journal - a cherry- coloured, plastic-covered agenda. Unable to sleep, CHE waits for the coffee to relieve his ASTHMA. CHE is bearded, 39 years old. A LIGHT flickers on the far side of the ravine. MORO Shit. A light -- ANGLE ON RAUL A Bolivian, picking up his M-1 rifle. RAUL Who goes there? VOICE Trinidad Detachment -- GUNFIRE BREAKS OUT. RAUL is firing across the river at the light. Incoming bullets whine through the camp. EVERYONE is awake and in a panic. ANGLE ON POMBO CHE's deputy, a tall Black Cuban, helping the weakened CHE aboard a horse. CHE's asthma worsens as the bullets fly. CHE Chino! The supplies! 3 ANGLE ON CHINO Chinese-Peruvian, round-faced and bespectacled, rounding up the frightened mounts. OTHER MEN load the horses with supplies - lashing them insecurely in their haste. It's getting light. SOLDIERS of the Bolivian Army can be seen across the ravine, firing through the trees. POMBO leads CHE's horse away from the gunfire. -

¡Patria O Muerte!: José Martí, Fidel Castro, and the Path to Cuban Communism

¡Patria o Muerte!: José Martí, Fidel Castro, and the Path to Cuban Communism A Thesis By: Brett Stokes Department: History To be defended: April 10, 2013 Primary Thesis Advisor: Robert Ferry, History Department Honors Council Representative: John Willis, History Outside Reader: Andy Baker, Political Science 1 Acknowledgements I would like to thank all those who assisted me in the process of writing this thesis: Professor Robert Ferry, for taking the time to help me with my writing and offer me valuable criticism for the duration of my project. Professor John Willis, for assisting me in developing my topic and for showing me the fundamentals of undertaking such a project. My parents, Bruce and Sharon Stokes, for reading and critiquing my writing along the way. My friends and loved-ones, who have offered me their support and continued encouragement in completing my thesis. 2 Contents Abstract 3 Introduction 4 CHAPTER ONE: Martí and the Historical Roots of the Cuban Revolution, 1895-1952 12 CHAPTER TWO: Revolution, Falling Out, and Change in Course, 1952-1959 34 CHAPTER THREE: Consolidating a Martían Communism, 1959-1962 71 Concluding Remarks 88 Bibliography 91 3 Abstract What prompted Fidel Castro to choose a communist path for the Cuban Revolution? There is no way to know for sure what the cause of Castro’s decision to state the Marxist nature of the revolution was. However, we can know the factors that contributed to this ideological shift. This thesis will argue that the decision to radicalize the revolution and develop a relationship with the Cuban communists was the only logical choice available to Castro in order to fulfill Jose Marti’s, Cuba’s nationalist hero, vision of an independent Cuba. -

The Post-Cold War Security Dilemma in the Transcaucasus

The Post-Cold War Security Dilemma In the Transcaucasus Garnik Nanagoulian, Fellow Weatherhead Center For International Affairs Harvard University May 2000 This paper was prepared by the author during his stay as a Fellow at the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs of Harvard University. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author and do not reflect those of the Armenian Government or of the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs 1 Introduction With the demise of the Soviet Union, the newly emerging countries of the Transcaucasus and Caspian regions were the objects of growing interest from the major Western powers and the international business community, neither of which had had access to the region since the early nineteenth century. The world’s greatest power, the United States, has never had a presence in this region, but it is now rapidly emerging as a major player in what is becoming a new classical balance of power game. One of the main attractions of the region, which has generated unprecedented interest from the US, Western Europe, Turkey, Iran, China, Pakistan and others, is the potential of oil and gas reserves. While it was private Western interests that first brought the region into the sphere of interest of policy makers in Western capitals, commercial considerations have gradually been subordinated to political and geopolitical objectives. One of these objectives—not formally declared, but at least perceived as such in Moscow—amounts to containment of Russia: by helping these states protect their newly acquired independence (as it is perceived in Washington), the US can keep Russia from reasserting any "imperial" plans in the region. -

Complete Issue

World Customs Journal March 2017 Volume 11, Number 1 ISSN: 1834-6707 (Print) 1834-6715 (Online) World Customs Journal March 2017 Volume 11, Number 1 International Network of Customs Universities World Customs Journal Published by the Centre for Customs and Excise Studies (CCES), Charles Sturt University, Australia and the University of Münster, Germany in association with the International Network of Customs Universities (INCU) and the World Customs Organization (WCO). The World Customs Journal is a peer-reviewed journal which provides a forum for customs professionals, academics, industry researchers, and research students to contribute items of interest and share research and experiences to enhance its readers’ understanding of all aspects of the roles and responsibilities of Customs. The Journal is published twice a year. The website is at: www.worldcustomsjournal.org. Guidelines for Contributors are included at the end of each issue. More detailed guidance about style is available on the Journal’s website. Correspondence and all items submitted for publication should be sent in Microsoft Word or RTF, as email attachments, to the Editor-in-Chief: [email protected]. ISSN: 1834-6707 (Print) 1834-6715 (Online) Volume 11, Number 1 Published March 2017 © 2017 CCES, Charles Sturt University, Australia and University of Münster, Germany INCU (www.incu.org) is an association that provides the WCO and other organisations with a single point of contact with universities and research institutes that are active in the field of customs research, education and training. Copyright. All rights reserved. Permission to use the content of the World Customs Journal must be obtained from the copyright owner. -

Review of Julia E. Sweig's Inside the Cuban Revolution

Inside the Cuban Revolution: Fidel Castro and the Urban Underground. By Julia E. Sweig. (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2002. xx, 255 pp. List of illustrations, acknowledgments, abbre- viations, about the research, notes, bibliography, index. $29.95 cloth.) Cuban studies, like former Soviet studies, is a bipolar field. This is partly because the Castro regime is a zealous guardian of its revolutionary image as it plays into current politics. As a result, the Cuban government carefully screens the writings and political ide- ology of all scholars allowed access to official documents. Julia Sweig arrived in Havana in 1995 with the right credentials. Her book preface expresses gratitude to various Cuban government officials and friends comprising a who's who of activists against the U.S. embargo on Cuba during the last three decades. This work, a revision of the author's Ph.D. dissertation, ana- lyzes the struggle of Fidel Castro's 26th of July Movement (M-26-7) against the Fulgencio Batista dictatorship from November 1956 to July 1958. Sweig recounts how the M-26-7 urban underground, which provided the recruits, weapons, and funds for the guerrillas in the mountains, initially had a leading role in decision making, until Castro imposed absolute control over the movement. The "heart and soul" of this book is based on nearly one thousand his- toric documents from the Cuban Council of State Archives, previ- ously unavailable to scholars. Yet, the author admits that there is "still-classified" material that she was unable to examine, despite her repeated requests, especially the correspondence between Fidel Castro and former president Carlos Prio, and the Celia Sánchez collection. -

Research and Reference Service

LBJ Library, NSF, box 21, Country, Latin America, Cuba, Chronology > ? Research and Reference Service CHRONOLOGY OF CUBAN EVENTS, 1963 R-167-64 October 23, 1964 This is a research report, not a statement of Agency policy w . - . .- COPY LBJ UBRARY CHRONOLOGY OF CUBAN EVENTS, 1963 The following were selected as the more significant developments in Cuban affairs during 1963. January 1 The Soviet news agency Novosti established an office in Havana. In a speech on the fourth anniversary of the Revolution, Fidel Castro reiterated the D-t Cuban ~olicvthat holds UD the revolution as a model for the Hemisphere. "We ape examples for the brother peoples of Latin America.... If the workers and people of Latin America had weapons as our people do, we would see what would happen.... We have the great historic task of bringfng this revolution forward, of serving as an example for the revolutionaries of Latin America- and within the socialist camp, which is and always will be our family." 7 The first TU-114 (~eroflot)turboprop aircraft on the new Moscow-Havana schedule arrived in Havana. 8 The Castro Government, r;-k~;..~:L;cd 62 local medical insurance clinics, assigning them to the Ministry of Public Health and closed 38 others for "lack of adequatet1 facilities. 8 A top-level Soviet military mission departed after spending several days in Cuba. Prensa Latina reported that the mission inspected a number of Soviet installations and conferred with Russian military leaders sta- tioned on the island. 11 The Congress of Women of the Americas was inaugurated in Havana with approximately 500 participants from most Latin American countries and observers from ~o&unistbloc countries. -

DEC 1990, VOL 21 No 2.Pdf

EDITOR'S NOTE The PhilippineJournalof Linguisticsis the official publication of the Linguistic Society of the Philippines. Itpublishes original studies in descriptive, comparative, historical, and areal linguistics. Although its primary interest is in linguistic theory, it also publishes papers on the application of theory to language teaching, sociolinguistics, psycholinguistics, anthropological linguistics, etc. Papers on applied linguistics should, however, be chiefly concerned with the principles which underlie specific techniques rather than with the mechanical aspects of such techniques. Articles are published in English,although papers written in Filipino, the national language of the Philippines, will occasionally appear. Since the Linguistic Society of the Philippines is composed of members whose paramount interests are the Philippine languages, papers on these and related languages are given priority in publication. This does not mean, however, that the journal will limit its scope to the Austronesian language family. Studies on any aspectoflanguagestrocturearewe!come. Manuscripts for publication, exchange journals, and books for review or listing should be sent to the Editor, Brother Andrew Gonzalez, FSC, De La Salle University, 2401 Taft Avenue, Manila, Philippines. Manuscripts from the United States and Europe should be sent to Dr. Lawrence A. Reid, Pacific and Asian Linguistics Institute, University of Hawaii, 1980 East-West Road, Honolulu, Hawaii 96822, U.S.A. Review Editor Ma. Lourdes S. Bautista, De La Salle University Managing Editor Teresita Erestain, De La Salle University Business Manager Angelita F. Alim, De La Salle University ©1990bytheLinguisticSocietyofthePhilippines The journal is distributed to members of the LinguisticSocietyofthePhilippinesand is paid for by their annual dues. The publication of the PhilippineJournalofLinguisticsis supported in part by the Summer InstituteofLinguisties(Philippines)andthePhilippineSocialScieneeCouneil. -

Cultura E Revolução Em Cuba Nas Memórias Literárias De Dois Intelectuais Exilados, Carlos Franqui E Guillermo Cabrera Infante (1951-1968)

BARTHON FAVATTO SUZANO JÚNIOR ENTRE O DOCE E O AMARGO: cultura e revolução em Cuba nas memórias literárias de dois intelectuais exilados, Carlos Franqui e Guillermo Cabrera Infante (1951-1968). ASSIS 2012 BARTHON FAVATTO SUZANO JÚNIOR ENTRE O DOCE E O AMARGO: cultura e revolução em Cuba nas memórias literárias de dois intelectuais exilados, Carlos Franqui e Guillermo Cabrera Infante (1951-1968). Dissertação apresentada à Faculdade de Ciências e Letras de Assis – UNESP – Universidade Estadual Paulista para obtenção do título de Mestre em História (Área de Conhecimento: História e Sociedade.) Orientador: Prof. Dr. Carlos Alberto Sampaio Barbosa. ASSIS 2012 Catalogação da Publicação Dados Internacionais de Catalogação na Publicação (CIP) Biblioteca da F.C.L. – Assis – UNESP Favatto Júnior, Barthon F272e Entre o doce e o amargo: cultura e revolução em Cuba nas memórias literárias de dois intelectuais exilados, Carlos Franqui e Guillermo Cabrera Infante (1951-1968) / Barthon Favatto Suzano Júnior. Assis, 2012 197 f. Dissertação de Mestrado – Faculdade de Ciências e Letras de Assis – Universidade Estadual Paulista. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Carlos Alberto Sampaio Barbosa 1. Cuba – História – Revolução, 1959. 2. Intelectuais e política. 3. Exílio. 4. Franqui, Carlos, 1921-2010. 5. Cabrera Infante, Guillermo, 1929-2005. I. Título. CDD 972.91064 AGRADECIMENTOS A realização de um trabalho desta envergadura não constitui tarefa fácil, tampouco é produto exclusivo do labor silencioso e solitário do pesquisador. Por detrás da capa que abre esta dissertação há inúmeros agentes históricos que imprimiram nas páginas que seguem suas importantes, peremptórias e indeléveis contribuições. Primeiramente, agradeço ao Prof. Dr. Carlos Alberto Sampaio Barbosa, amigo e orientador nesta, em passadas e em futuras jornadas, que como um maestro soube conduzir com rigor e sensibilidade intelectual esta sinfonia. -

Aes Corporation

THE AES CORPORATION THE AES CORPORATION The global power company A Passion to Serve A Passion A PASSION to SERVE 2000 ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL REPORT THE AES CORPORATION 1001 North 19th Street 2000 Arlington, Virginia 22209 USA (703) 522-1315 CONTENTS OFFICES 1 AES at a Glance AES CORPORATION AES HORIZONS THINK AES (CORPORATE OFFICE) Richmond, United Kingdom Arlington, Virginia 2 Note from the Chairman 1001 North 19th Street AES OASIS AES TRANSPOWER Arlington, Virginia 22209 Suite 802, 8th Floor #16-05 Six Battery Road 5 Our Annual Letter USA City Tower 2 049909 Singapore Phone: (703) 522-1315 Sheikh Zayed Road Phone: 65-533-0515 17 AES Worldwide Overview Fax: (703) 528-4510 P.O. Box 62843 Fax: 65-535-7287 AES AMERICAS Dubai, United Arab Emirates 33 AES People Arlington, Virginia Phone: 97-14-332-9699 REGISTRAR AND Fax: 97-14-332-6787 TRANSFER AGENT: 83 2000 AES Financial Review AES ANDES FIRST CHICAGO TRUST AES ORIENT Avenida del Libertador COMPANY OF NEW YORK, 26/F. Entertainment Building 602 13th Floor A DIVISION OF EQUISERVE 30 Queen’s Road Central 1001 Capital Federal P.O. Box 2500 Hong Kong Buenos Aires, Argentina Jersey City, New Jersey 07303 Phone: 852-2842-5111 Phone: 54-11-4816-1502 USA Fax: 852-2530-1673 Fax: 54-11-4816-6605 Shareholder Relations AES AURORA AES PACIFIC Phone: (800) 519-3111 100 Pine Street Arlington, Virginia STOCK LISTING: Suite 3300 NYSE Symbol: AES AES ENTERPRISE San Francisco, California 94111 Investor Relations Contact: Arlington, Virginia USA $217 $31 Kenneth R. Woodcock 93% 92% AES ELECTRIC Phone: (415) 395-7899 $1.46* 91% Senior Vice President 89% Burleigh House Fax: (415) 395-7891 88% 1001 North 19th Street $.96* 18 Parkshot $.84* AES SÃO PAULO Arlington, Virginia 22209 Richmond TW9 2RG $21 Av. -

Members of the Linguistic Society of the Phiuppines 1985-1986

MEMBERS OF THE LINGUISTIC SOCIETY OF THE PHIUPPINES 1985-1986 1. TED ABADIANO, JR., TAP, Inc., No.2 Legazpi, Phil-Am Homes, Quezon City 2. HUSEN ABAS, Language Center, Hasanuddin University, Jalan Sinu 199, Ujung Pandang, Indonesia 3. SHIRLEY ABBOT, Summer Institute of Linguistics, 12 Horseshoe Drive, Quezon City 4. LARRY ALLEN, Summer Institute of Linguistics, 12 Horseshoe Drive, Quezon City 5. LYDIA D. AMOYO, Borongan, Eastern Samar 6. CORAZON D. ANDAL, Pablo Borbon Memorial Institute of Technology, Batangas City 7. AZUCENA L. ANDRES, 3 Javier St., Taytay, Rizal 8. EPIFANIA G. ANGELES, Institute of National Language, 4th Floor, LDCI Bldg., Cor. EDSA & East Ave., Quezon City 9. EVAN ANTWORTH, Summer Institute of Linguistics, 12 Horseshoe Drive, Quezon City 10. ROSA V. APIN, Institute of National Language, 4th Floor, LDCI Bldg., Cor. EDSA & East Ave., Quezon City 11. MALCOM ARMOUR, Summer Institute of Linguistics, 12 Horseshoe Drive, Que- zon City , 12. BAGABAG LIBRARY, Summer Institute of Linguistics, 12 Horseshoe Drive, Quezon City 13. BAGUIO VACATION NORMAL SCHOOL, Summer Institute of Linguistics, 12 Horseshoe Drive, Quezon City 14. SABINA BAGUNU, Isabela State University, Cagayan, Isabela 15. ELPIDIO S. BAJAO, US Peace Corps Office, 2139 Fidel Reyes St., Malate, Manila 16. EDILBERTA C. BALA, Language Study Center, Philippine Normal College, Taft Avenue, Manila 17. ESTEUTA D. BALGOS, 2915 E. Rodriguez St., Malibay. Pasay City 18. DONALD BARR, Summer Institute of Linguistics, 12 Horseshoe Drive, Quezon City ; 19. NICOLASITA P. BARRIDO, College of Education, University of Santo Tomas, Espana, Manila ,; 20. REMEDIOS T. BARROSO, Bukidnon State College, Malaybalay, Bukidnon . 21. MA. LOURDES S.