Ideology and Utopianism in Wartime Japan an Essay on the Subversiveness of Christian Eschatology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nakajima Michiko and the 15-Woman Lawsuit Opposing Dispatch of Japanese Self-Defense Forces to Iraq

Volume 5 | Issue 10 | Article ID 2551 | Oct 01, 2007 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Gendered Labor Justice and the Law of Peace: Nakajima Michiko and the 15-Woman Lawsuit Opposing Dispatch of Japanese Self-Defense Forces to Iraq Tomomi Yamaguchi, Norma Field Gendered Labor Justice and the Law of Peace: Nakajima Michiko and the 15- Woman Lawsuit Opposing Dispatch of Japanese Self-Defense Forces to Iraq Tomomi YAMAGUCHI and Norma Field Introduction In 2004, then Prime Minister Jun'ichiro Koizumi, in response to a request from the United States, sent a contingent of 600 Self- Defense Force troops to Samawa, Iraq, for the Nakajima Michiko from the 2002 calendar, purpose of humanitarian relief and To My Sisters, a photo of her from her reconstruction. Given that Article 9 of the student days at the Japanese Legal Training Japanese Constitution eschews the use of and Research Institute. A larger view of the military force in the resolution of conflict, this same page can be viewed here. was an enormously controversial step, going further than previous SDF engagements as part Nakajima Michiko, a feminist labor lawyer, led of UN peacekeeping operations, whichone such group of plaintiffs, women ranging in themselves had been criticized by opposition age from 35 to 80. Each of the fifteen had her forces as an intensification of the incremental moment in court, stating her reasons, based on watering-down of the "no-war clause" from as her life experiences, for joining the suit. This early as the 1950s. gave particular substance to the claim that Article 9 guarantees the "right to live in Many citizens, disappointed by the weakness of peace"—the centerpiece of many of these parliamentary opposition since a partiallawsuits, a claim that seems to have been first winner-take-all, first-past-the-post system was made when Japan merely contributed 13 billion introduced in 1994, and frustrated by a dollars for the Gulf War effort. -

The Birth of the Parliamentary Democracy in Japan: an Historical Approach

The Birth of the Parliamentary Democracy in Japan: An Historical Approach Csaba Gergely Tamás * I. Introduction II. State and Sovereignty in the Meiji Era 1. The Birth of Modern Japan: The First Written Constitution of 1889 2. Sovereignty in the Meiji Era 3. Separation of Powers under the Meiji Constitution III. The Role of Teikoku Gikai under the Meiji Constitution (明治憲法 Meiji Kenp ō), 1. Composition of the Teikoku Gikai ( 帝國議会) 2. Competences of the Teikoku Gikai IV. The Temporary Democracy in the 1920s 1. The Nearly 14 Years of the Cabinet System 2. Universal Manhood Suffrage: General Election Law of 1925 V. Constitutionalism in the Occupation Period and Afterwards 1. The Constitutional Process: SCAP Draft and Its Parliamentary Approval 2. Shōch ō ( 象徴) Emperor: A Mere Symbol? 3. Popular Sovereignty and the Separation of State Powers VI. Kokkai ( 国会) as the Highest Organ of State Power VII. Conclusions: Modern vs. Democratic Japan References I. INTRODUCTION Japanese constitutional legal history does not constitute a part of the obligatory legal curriculum in Hungary. There are limited numbers of researchers and references avail- able throughout the country. However, I am convinced that neither legal history nor comparative constitutional law could be properly interpreted without Japan and its unique legal system and culture. Regarding Hungarian-Japanese legal linkages, at this stage I have not found any evidence of a particular interconnection between the Japanese and Hungarian legal system, apart from the civil law tradition and the universal constitutional principles; I have not yet encountered the Hungarian “Lorenz von Stein” or “Hermann Roesler”. * This study was generously sponsored by the Japan Foundation Short-Term Fellowship Program, July-August, 2011. -

Chronology of the Japanese Emperors Since the Mid-Nineteenth Century

CHRONOLOGY OF THE JAPANESE EMPERORS SINCE THE MID-NINETEENTH CENTURY K}mei (Osahito) Birth and death: 1831–1867 Reign: 1846–1867 Father: Emperor Ninkō Mother: Ōgimachi Naoko (concubine) Wife: Kujō Asako (Empress Dowager Eishō) Important events during his reign: 1853: Commodore Matthew Perry and his ‘Black Ships’ arrive at Uraga 1854: Kanagawa treaty is signed, Japan starts to open its gates 1858: Commercial treaty with the U.S. and other western powers is signed 1860: Ii Naosuke, chief minister of the shogun, is assassinated 1863: British warships bombard Kagoshima 1864: Western warships bombard Shimonoseki 1866: Chōshū-Satsuma alliance is formed Meiji (Mutsuhito) Birth and death: 1852–1912 Reign: 1867–1912 Father: Emperor Kōmei Mother: Nakayama Yoshiko (concubine) Wife: Ichijō Haruko (Empress Dowager Shōken) Important events during his reign: 1868: Restoration of imperial rule (Meiji Restoration) is declared 1869: The capital is moved to Tokyo (Edo) 1872: Compulsory education is decreed 1873: Military draft is established 1877: The Satsuma rebellion is suppressed 1885: The cabinet system is adopted 336 chronology of the japanese emperors 1889: The Meiji Constitution is promulgated 1890: The First Diet convenes; Imperial Rescript on Education is proclaimed 1894–5: The First Sino-Japanese War 1902: The Anglo-Japanese Alliance is signed 1904–5: The Russo-Japanese War 1911: Anarchists are executed for plotting to murder the emperor Taish} (Yoshihito) Birth and death: 1879–1926 Reign: 1912–1926 Father: Emperor Meiji Mother: Yanagihara Naruko -

Max M. Ward H O U GCRIME

T Max M. Ward H O U GCRIME H Ideology & State Power in Interwar Japan T THOUGHT CRIME T H O U G H asia pacific Asia- Pacific Culture, Politics, and Society Editors: Rey Chow, Michael Dutton, H. D. Harootunian, and Rosalind C. Morris A Study of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute, Columbia University T T Max M. Ward H O U G H CRIME T Ideology and State Power in Interwar Japan Duke University Press Durham and London 2019 © 2019 duke university press. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Courtney Baker Typeset in Arno pro by Westchester Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Ward, Max M., [date] author. Title: Thought crime : ideology and state power in interwar Japan / Max M. Ward. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2019. | Series: Asia Pacific | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2018031281 (print) | lccn 2018038062 (ebook) isbn 9781478002741 (ebook) isbn 9781478001317 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9781478001652 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: lcsh: Lese majesty— Law and legislation— Japan— History—20th century. | Po liti cal crimes and offenses— Japan— History—20th century. | Japan— Politics and government— 1926–1945. | Japan— Politics and government—1912–1945. | Japan— History—1912–1945. Classification: lcc knx4438 (ebook) | lcc knx4438 .w37 2019 (print) lc rec ord available at https:// lccn . loc . gov / 2018031281 Cover art: Newspaper clippings from the Yomiuri Shimbun, 1925-1938. Courtesy of the Yomiuri Shimbun. Dedicated to the punks, in the streets and the ivory towers contents Preface: Policing Ideological Threats, Then and Now ix Acknowl edgments xv introduction. -

Appendix SCAPIN 919, “Removal and Exclusion of Diet Member”

Appendix SCAPIN 919, “Removal and Exclusion of Diet Member” May 3, 1946 a. As Chief Secretary of the Tanaka Cabinet from 1927 to 1929, he necessarily shares responsibility for the formulation and promulgation without Diet approval of amendments to the so-called Peace Preservation Law which made that law the government’s chief legal instrument for the suppression of freedom of speech and freedom of assembly, and made possible the denunciation, terror- ization, seizure, and imprisonment of tens of thousands of adherents to minor- ity doctrines advocating political, economic, and social reform, thereby preventing the development of effective opposition to the Japanese militaristic regime. b. As Minister of Education from December 1931 to March 1934, he was responsible for stifling freedom of speech in the schools by means of mass dismissals and arrests of teachers suspected of “leftist” leanings or “dangerous thoughts.” The dismissal in May 1933 of Professor Takigawa from the faculty of Kyoto University on Hatoyama’s personal order is a flagrant illustration of his contempt for the liberal tradition of academic freedom and gave momentum to the spiritual mobilization of Japan, which under the aegis of the military and economic cliques, led the nation eventually into war. c. Not only did Hatoyama participate in thus weaving the pattern of ruth- less suppression of freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, and freedom of thought, hut he also participated in the forced dissolution of farmer-labor bodies. In addition, his indorsement of totalitarianism, specifically in its appli- cation to the regimentation and control of labor, is a matter of record. -

Abschlussarbeiten Am Japan-Zentrum Der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München

DEPARTMENT FÜR ASIENSTUDIEN JAPAN-ZENTRUM Abschlussarbeiten am Japan-Zentrum der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München Munich University Japan Center Graduation Theses herausgegeben von / edited by Steffen Döll, Martin Lehnert, Peter Pörtner, Evelyn Schulz, Klaus Vollmer, Franz Waldenberger Band 1 Japan-Zentrum der LMU 2013 Vorwort der Herausgeber Bei den Beiträgen in der vorliegenden Schriftenreihe handelt es sich um Abschluss- arbeiten des Japan-Zentrums der LMU. Eine große Bandbreite an Themen und Forschungsrichtungen findet sich darin vertreten. Ziel der Reihe ist es, herausragende Arbeiten einer breiteren Öffentlichkeit zugänglich zu machen. Es wird davon ab- gesehen, inhaltliche oder strukturelle Überarbeitungen vorzunehmen; die Typoskripte der Bachelor-, Master- und Magisterarbeiten werden praktisch unverändert ver- öffentlicht. Editors’ Foreword The present series comprises select Bachelor, Master and Magister Artium theses that were submitted to the Japan Center of Munich University and address a broad variety of topics from different methodological perspectives. The series’ goal is to make available to a larger academic community outstanding studies that would otherwise remain inaccessible and unnoticed. The theses’ typescripts are published without revisions with regards to structure and content and closely resemble their original versions. Moritz Munderloh The Imperial Japanese Army as a Factor in Spreading Militarism and Fascism in Prewar Japan Magisterarbeit an der LMU München, 2012 Japan-Zentrum der LMU Oettingenstr. 67 -

Myths of Hakkō Ichiu: Nationalism, Liminality, and Gender

Myths of Hakko Ichiu: Nationalism, Liminality, and Gender in Official Ceremonies of Modern Japan Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Teshima, Taeko Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 01/10/2021 21:55:25 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/194943 MYTHS OF HAKKŌ ICHIU: NATIONALISM, LIMINALITY, AND GENDER IN OFFICIAL CEREMONIES OF MODERN JAPAN by Taeko Teshima ______________________ Copyright © Taeko Teshima 2006 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the GRADUATE PROGRAM IN COMPARATIVE CULTURAL AND LITERARY STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For a Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2 0 0 6 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Taeko Teshima entitled Myths of Hakkō Ichiu: Nationalism, Liminality, and Gender in Official Ceremonies of Modern Japan and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _________________________________________________Date: 6/06/06 Barbara A. Babcock _________________________________________________Date: 6/06/06 Philip Gabriel _________________________________________________Date: 6/06/06 Susan Hardy Aiken Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. -

Downloaded and Shared for Non-Commercial Purposes, Provided Credit Is Given to the Author

Crossing Empire’s Edge JOSHUA FOGEL, GENERAL EDITOR For most of its past, East Asia was a world unto itself. The land now known as China sat roughly at its center and was surrounded by a number of places now called Japan, Korea, Vietnam, Mongolia, and Tibet, as well as a host of lands absorbed into one of these. The peoples and cultures of these lands interacted among themselves with virtually no reference to the outside world before the dawn of early modern times. The World of East Asia is a book series that aims to support the production of research on the interactions, both historical and contemporary, between and among these lands and their cultures and peoples and between East Asia and its Central, South, and Southeast Asian neighbors. series titles Crossing Empire’s Edge Foreign Ministry Police and Japanese Expansionism in Northeast Asia, by Erik Esselstrom Memory Maps The State and Manchuria in Postwar Japan, by Mariko Asano Tamanoi THE WORLD OF EAST ASIA Crossing Empire’s Edge Foreign Ministry Police and Japanese Expansionism in Northeast Asia Erik Esselstrom University of Hawai‘i Press HONOLULU © 2009 University of Hawai‘i Press Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Esselstrom, Erik. Crossing empire's edge: Foreign Ministry police and Japanese expansion in Northeast Asia / by Erik Esselstrom. p. cm.—(The world of East Asia) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8248-3231-5 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Intelligence service—Japan. 2. Consular police—Japan. 3. Japan—Foreign relations—Korea. 4. Korea—Foreign relations—Japan. 5. Japan—Foreign relations—China. -

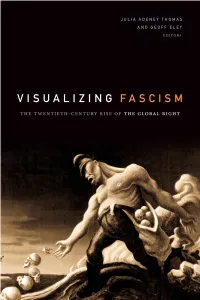

Visualizing FASCISM This Page Intentionally Left Blank Julia Adeney Thomas and Geoff Eley, Editors

Visualizing FASCISM This page intentionally left blank Julia Adeney Thomas and Geoff Eley, Editors Visualizing FASCISM The Twentieth- Century Rise of the Global Right Duke University Press | Durham and London | 2020 © 2020 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Julienne Alexander / Cover designed by Matthew Tauch Typeset in Minion Pro and Haettenschweiler by Copperline Books Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Eley, Geoff, [date] editor. | Thomas, Julia Adeney, [date] editor. Title: Visualizing fascism : the twentieth-century rise of the global right / Geoff Eley and Julia Adeney Thomas, editors. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers:lccn 2019023964 (print) lccn 2019023965 (ebook) isbn 9781478003120 (hardback : acid-free paper) isbn 9781478003762 (paperback : acid-free paper) isbn 9781478004387 (ebook) Subjects: lcsh: Fascism—History—20th century. | Fascism and culture. | Fascist aesthetics. Classification:lcc jc481 .v57 2020 (print) | lcc jc481 (ebook) | ddc 704.9/49320533—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019023964 lc ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019023965 Cover art: Thomas Hart Benton, The Sowers. © 2019 T. H. and R. P. Benton Testamentary Trusts / UMB Bank Trustee / Licensed by vaga at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. This publication is made possible in part by support from the Institute for Scholarship in the Liberal Arts, College of Arts and Letters, University of Notre Dame. CONTENTS ■ Introduction: A Portable Concept of Fascism 1 Julia Adeney Thomas 1 Subjects of a New Visual Order: Fascist Media in 1930s China 21 Maggie Clinton 2 Fascism Carved in Stone: Monuments to Loyal Spirits in Wartime Manchukuo 44 Paul D. -

1 About Ōtsuka Kinnosuke (1892-1977) – His Life, Work and Role in the Relations Between Japan and East Germany Education

About Ōtsuka Kinnosuke (1892-1977) – his life, work and role in the relations between Japan and East Germany Education The Marxist economist Ōtsuka Kinnosuke was born in Kanda, Tōkyō in 1892 to a proletarian family. According to the curriculum vitae written by himself his parents never had attended school. Ōtsuka went to the Kōbe Higher Commercial School (today Kōbe University) from 1910 to 1914 and he was even exempted from paying the school fees. However, because of a favourable article about the anarchist Emma Goldman and her views in the students’ magazine („Shugisha ‘Gōrudoman’” in “Kōbe kōtō shōgyō gakkō gakuyūkaihō”, no. 58, May 1912, p. 331-336) the headmaster of the school and the head of the library were reprimanded by the Ministry of Education. All editions of the students’ magazine were confiscated and Ōtsuka was deprived of his privilege concerning the school fees. Nevertheless, he continued his education at Tōkyō Higher Commercial School (today Hitotsubashi University) where he graduated in 1916. Directly after his graduation he started to work and teach at the same school. From 1919 until 1923 Ōtsuka studied abroad at the Columbia University, New York, the London School of Economics and Political Science and the Berlin University (today Humboldt University) with a scholarship of the Japanese Ministry of Education. His stay coincided with a time of upheaval in America and Europe. He witnessed strikes and the discriminating treatment of black people in America, whereas in Germany inflation was at its height accompanied by strikes and social unrest. In London Ōtsuka attended lectures by the socialist and reformer Sidney Webb. -

The Retrial of the Yokohama Incident: a Six Decade Battle for Human Dignity

Volume 4 | Issue 5 | Article ID 1980 | May 06, 2006 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus The Retrial of the Yokohama Incident: A Six Decade Battle for Human Dignity Nishimura Hideki The Retrial of the “Yokohamapursued between 1942 and 1945. The horror Incident”: A Six Decade Battle for experienced by those innocently targeted by the state of that time was worthy of Stalinism Human Dignity at its peak. The secret police, procurators, and the judiciary persisted in the actions described By Nishimura Hideki here to the point of securing many of the guilty Translated by Aaron Skabelund verdicts and carrying out the punishments even after the Japanese surrender. [It is well known that Japan’s neighbors, The victims pursued their search for justice and especially China and South Korea, are unhappy apology through countless judicial applications at what they see as Japan’s failure to accept and reverses over more than six decades until a responsibility, apologize and compensate final judgment was announced on 9 February victims for its wartime crimes and colonial 2006 (shortly after the following article was abuses. What is less well known, however, is written). By then, all the victims in the incident the Japanese state’s reluctance to address the had died, and it was their families and same questions of justice and human rights in supporters that persisted in the action in their the case of its own citizens who were victims of name. crimes committed by the prewar or wartime The court ruled as the defense (the Japanese state. No Japanese court has ever adequately state) urged it to, dismissing the case on addressed the criminality of any action by the grounds of lack of evidence. -

Relações Japão - Asean: a Doutrina Fukuda E a Cooperação Para a Paz Regional

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DA PARAÍBA CENTRO DE CIÊNCIAS SOCIAIS APLICADAS DEPARTAMENTO DE RELAÇÕES INTERNACIONAIS RELAÇÕES JAPÃO - ASEAN: A DOUTRINA FUKUDA E A COOPERAÇÃO PARA A PAZ REGIONAL ANA MARIA GENEROSO DA SILVA JOÃO PESSOA - PB 2020 ANA MARIA GENEROSO DA SILVA RELAÇÕES JAPÃO - ASEAN: A DOUTRINA FUKUDA E A COOPERAÇÃO PARA A PAZ REGIONAL Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso apresentado como requisito parcial para conclusão do Curso de Graduação em Relações Internacionais da Universidade Federal da Paraíba. Orientador: Prof. Marcos Alan Shaikhzadeh V. Ferreira JOÃO PESSOA - PB 2020 Catalogação na publicação Seção de Catalogação e Classificação S586r Silva, Ana Maria G da. Relações Japão - ASEAN: a Doutrina Fukuda e a cooperação para a paz regional / Ana Maria G da Silva. - João Pessoa, 2020. 50 f. Orientação: Marcos Alan S V Ferreira. Monografia (Graduação) - UFPB/CCSA. 1. ASEAN. 2. Japão. 3. cooperação regional. 4. pacificação. I. S V Ferreira, Marcos Alan. II. Título. UFPB/CCSA AGRADECIMENTOS Primeiramente, agradeço aos meus familiares, que, apesar dos mais de 3.000 km de distância, sempre mantiveram contato comigo durante meus anos universitários. Agradeço aos servidores do Departamento de Relações Internacionais da Universidade Federal da Paraíba por suas contribuições em minha jornada acadêmica. Em especial, agradeço ao meu professor orientador, Marcos Alan Shaikhzadeh V. Ferreira, por seus ensinamentos, por sua disposição e por sua paciência para me ajudar na realização deste trabalho. Agradeço também aos colegas que conheci durante a Graduação por sua boa companhia e por sua cooperação em trabalhos conjuntos. Por fim, agradeço à cidade de João Pessoa por seu acolhimento durante minha estadia.