F' F LJ Monmouth County New Jersey 13- Kg'af\IS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection Water Resource Management

NJ Department of Environmental Protection Water Monitoring and Standards Bureau of Marine Water Monitoring COOPERATIVE COASTAL MONITORING PROGRAM 2016 Summary Report May 2017 COOPERATIVE COASTAL MONITORING PROGRAM 2016 Summary Report New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection Water Resource Management Division of Water Monitoring and Standards Bruce Friedman, Director Bureau of Marine Water Monitoring Bob Schuster, Bureau Chief May 2017 Report prepared by: Virginia Loftin, Program Manager Cooperative Coastal Monitoring Program Bureau of Marine Water Monitoring Cover Photo – New Jersey Coastline (photo by Steve Jacobus, NJDEP) Introduction The Cooperative Coastal Monitoring Program (CCMP) is coordinated by the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection’s Bureau of Marine Water Monitoring. The CCMP assesses coastal water quality and investigates sources of water pollution. The information collected under the CCMP assists the DEP in responding to immediate public health concerns arising from contamination in coastal recreational bathing areas. Agencies that participate in the CCMP perform sanitary surveys of beach areas and monitor concentrations of bacteria in nearshore ocean and estuarine waters to assess the acceptability of these waters for recreational bathing. These activities and the resulting data are used to respond to immediate public health concerns associated with recreational water quality and to eliminate the sources of fecal contamination that impact coastal waters. Funding for the CCMP comes from the NJ Coastal Protection Trust Fund and the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Beaches Environmental Assessment and Coastal Health (BEACH) Act grants. BEACH Development and Implementation grants were awarded in the years 2001 through 2016. DEP designs the beach sampling and administers the communication, notification and response portion of the CCMP. -

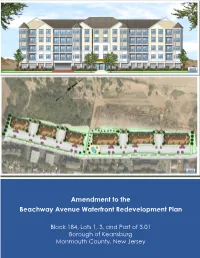

Amendment to the Beachway Avenue Waterfront Redevelopment Plan

Insert Picture (7.5” x 8.75”) Amendment to the Beachway Avenue Waterfront Redevelopment Plan Block 184, Lots 1, 3, and Part of 3.01 Borough of Keansburg Monmouth County, New Jersey {00031724;v1/ 16-044/012} Amendment to the Beachway Avenue Waterfront Redevelopment Plan Block 184, Lots 1 & 3, and part of 3.01 Borough of Keansburg Monmouth County, New Jersey First Reading / Introduction: May 17, 2017 Endorsed by Planning Board: Second Reading / Adoption: Prepared for: Prepared by: T&M Associates Borough of Keansburg 11 Tindall Road Monmouth County, New Jersey Middletown, NJ 07748 Stan Slachetka, P.P., AICP NJ Professional Planner No.: LI-03508 The original of this document was signed and sealed in accordance with New Jersey Law Amendment to the Beachway Avenue Waterfront Redevelopment Plan Borough of Keansburg, Monmouth County, New Jersey Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 1 Redevelopment Plan Amendment ............................................................................................ 2 Section 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................ 2 Section 2. The Public Purpose ................................................................................................ 4 2.1 Goals and Objectives ................................................................................................. 4 2.2 Relationship to Local Objectives -

Raritan Bay Report 2016

Two States – One Bay A bi-state conversation about the future of Raritan Bay Bill Schultz/Raritan Riverkeeper Bill Schultz/Raritan Introduction The Two States: One Bay conference, convened on June 12, 2015 by the Sustainable Raritan River Initiative (SRRI) at Rutgers University and the New York-New Jersey Harbor & Estuary Program (HEP), brought together more than 200 representatives from federal, state and local governments, educational institutions, non-profit organizations, and businesses to focus on Raritan Bay. During plenary and working sessions where regional and bi-state issues and cooperation were the primary focus, conference participants examined the key topic areas of water quality, climate resiliency, habitat conservation and restoration, fish and shellfish management, and public access. This report identifies the insights and opportunities raised at the conference, including possible strategies to address ongoing bi-state challenges to ensure the stewardship and vitality of Raritan Bay. The Sustainable Raritan River Initiative and the New York-New Jersey Harbor & Estuary Program invite stakeholders from both New York and New Jersey to join us in taking next steps towards greater bi-state cooperation in addressing the challenges facing Raritan Bay. Overview Raritan Bay, roughly defined as the open waters and shorelines from the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge to the tidal reach of the Raritan River at New Brunswick, New Jersey, and out to Sandy Hook, provides important habitat, fishery resources, and recreational benefits to the New York and New Jersey region. These resources are enjoyed by more than one million nearby residents of the two states, as well as many annual visitors from outside the region. -

Investment Highlights

ABERDEEN OFFICE COMPLEX 675 LINE RD ABERDEEN, NJ 07747 18,000 SF of Office Buildings in Great Location with Prime Access to GS Parkway, NJ Turnpike, Routes 9, 18, 33, 34, 35, 36 & 79 Located 2 Minutes from Parkway Exit 117 Presented by Richel Commercial Brokerage Steve Richel, Gregory Elmiger | 732.720.0538 | www.richelcb.com PROPERTY OVERVIEW Address: 675 Line Road Aberdeen, NJ 07747 Block/Lot: Block 12- Lot 7.01 Acres: 2.82 Office RBA: 18,600 +/- RSF Occupancy: 100% Location Overview: The property is centrally located and in close proximity to the Garden State Parkway Exit 117A, NJ Turnpike, Routes 9, 18, 33, 34, 35, 36 & 79 Asking Price: $2,400,000 or $129 Per Square Foot 2 PROPERTY OVERHEAD VIEW Small Professional Office Park Four Buildings, 18,000 SF NRA, Abundant Parking 3 OVERVIEW OF ABERDEEN, NJ • Aberdeen is part of the Raritan Bayshore Region that features dense residential neighborhoods, maritime history, and the natural beauty of the Raritan Bay coastline. • As of the 2010 United States Census, the township's population was 18,210 reflecting an increase of 756 (+4.3%) from the 17,454 counted in the 2000 Census, which had in turn increased by 416 (+2.4%) from the 17,038 counted in the 1990 Census. • In terms of distances, the property is located approximately 6 minutes from the Aberdeen Train Station, 19 minutes from Fast Ferry to New York City and 30 minutes to Newark Airport. 4 PROSPEROUS SUBURBAN MARKET Aberdeen’s $92k Median Household Income is almost double the US Average ABERDEEN 5 IDEALLY LOCATED IN CENTRAL NEW JERSEY 675 Line Road Office Complex is in close proximity to all major highways making this location ideally suited to satisfy any business with logistical needs in Central New Jersey. -

New Jersey Sea Grant Final Report Identifying and Claiming The

New Jersey Sea Grant Final Report Identifying and Claiming the Coastal Commons in Industrialized and Gentrified Places Co-Principal Investigators: Bonnie J. McCay, Rutgers the State University, New Brunswick, NJ Andrew Willner, NY/NJ Baykeeper, Sandy Hook, Highlands, NJ Associate: Deborah A. Mans, NY/NJ Baykeeper, Sandy Hook, Highlands, NJ Sheri Seminski, Associate Director, NJ Center for Environmental Indicators Graduate Research Assistant: Johnelle Lamarque, Rutgers the State University, New Brunswick Satsuki Takahashi, Rutgers the State University, New Brunswick Abstract The coastal region of New Jersey, like that of most other coastal states, is imbued with a mixture of private, public, and common property rights, including the public trust doctrine. This project, which is focused on the bayshore region of the Raritan-Hudson Estuary and the neighboring northeastern tip of the New Jersey shore, will examine the changing nature of property and access rights in places that are both industrialized and gentrified. Through interviews and archival work, we will also identify the existence of and potentials for local and extra-local institutions that support public and common property rights. Institutions of interest range from local ordinances, zoning, and planning to the state-wide CAFRA permitting system to court cases, legal settlements, and applications of the state's public trust doctrine. Of particular importance are the following common property rights: a "working waterfront" accessible to commercial and recreational fishermen, safe and productive coastal waters, and public access to the beaches, bays, and inshore waters. Industrialization has long narrowed these rights because of its effects on available waterfront and on water quality. Gentrification also threatens such rights because of the competition it creates for waterfront and the privatization of access that often follows. -

Keansburg Borough Strategic Recovery Planning Report

Keansburg Borough Strategic Recovery Planning Report Keansburg Borough Strategic Recovery Planning Report Adopted June 25, 2014 Prepared by: T&M Associates 11 Tindall Road Middletown, NJ 07748 ______________________ Stan C. Slachetka, PP, AICP NJ Professional Planner No.: 03508 The original of this document was signed and sealed in accordance with New Jersey Law. KEANSBURG BOROUGH — STRATEGIC RECOVERY PLANNING REPORT Executive Summary When Superstorm Sandy struck the coast of New Jersey on October 29, 2012, it brought extensive damage to Keansburg Borough from both storm surge and wind damage. Protective dunes were breached by storm waters at four separate locations, and 2.6 miles of dunes were substantially damaged or washed away. Flood waters ranging from two to six feet in depth inundated approximately 50 percent of the structures in the Borough. Five (5) homes were destroyed by Superstorm Sandy and 347 were substantially damaged. Approximately 40,400 cubic yards of storm damage debris littered the Borough. Trees and power lines throughout the Borough fell. The Borough also faced total power outages for up to 14 days. This list of impacts that Superstorm Sandy had on Keansburg is not exhaustive; the remaining impacts are extensive and will be identified and discussed throughout this Strategic Recovery Planning Report. Both in preparation for and in response to Superstorm Sandy, Keansburg Borough’s actions have been comprehensive. Before and during Superstorm Sandy’s landfall, Keansburg evacuated residents and rescued stranded residents. In the days and weeks immediately following Superstorm Sandy, Keansburg barricaded flooded roads and hazards, patrolled the community, secured evacuated areas, deposited 40,400 cubic yards of storm-related debris in a temporary staging area, and performed inspections of 1,804 homes and 61 commercial properties in order to determine which properties were safe for habitation. -

Vulnerability of New Jersey's Coastal Habitats to Sea Level Rise

Vulnerability of New Jersey’s Coastal Habitats to Sea Level Rise Richard G. Lathrop Jr. Aaron Love January 2007 Grant F. Walton Center for Remote Sensing & Spatial Analysis Rutgers University In partnership with the American Littoral Society Highlands, New Jersey 14 College Farm Road Sandy Hook New Brunswick, NJ 08901-8551 Highlands, NJ 07732 www.crssa.rutgers.edu www.littoralsociety.org 1. Introduction Sea level rise is a well documented physical reality that is impacting New Jersey’s coastline. The recent historical levels of sea level rise along the New Jersey coast is generally thought to be about 3-4 mm/yr, while predicted future rates are expected to increase to 6 mm/yr (Cooper et al., 2005; Psuty and Ofiara, 2002). The hazards posed by sea level rise and severe coastal storms has instigated a number of studies examining the issue here in New Jersey as well as elsewhere in the Mid-Atlantic region (Cooper et al., 2005; Psuty and Ofiara, 2002; Gornitz et al., 2002; Rosenwieg and Solecki, 2001; Field et al., 2000; Najjar et al., 2000). The developed nature of New Jersey’s coastline makes it vulnerable to flooding and inundation and cause for concern by both government officials and the public alike. New Jersey’s sandy barrier beaches are dynamic features that respond in a generally predictable manner, migrating landward by storm overwash as the shoreline is also retreating due to erosion (Psuty and Ofiara, 2002; Phillips, 1986). Historically, societal response to sea level rise has been one of trying to short-circuit this natural process and to “hold the line.” Along the New Jersey coastline, as elsewhere in the Mid-Atlantic region, shoreline protection activities such as shoreline armoring (e.g., bulkheading, riprap or other solid beach fill) and/or beach nourishment have been extensively employed to halt shoreline erosion and maintain the coastline in place. -

Master Plan Re-Examination June 2012

KEANSBURG BOROUGH PLANNING BOARD MEMBERS Owen McKenna, Chair Anthony DiPompa Ginger Rogan Mayor Lisa Strydio Martin Flynn Daniel Strydio James Cocuzza, Jr. Chris Hoff Thomas Foley Mary Foley (Alternate 1) John Donohue (Alternate 2) Kevin Kennedy, Esq. Attorney Joseph May, PE, Engineer Kathy Burgess, Secretary Prepared by: Eleven Tindall Road Middletown, New Jersey 07748 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION PAGE INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 1.0 REQUIREMENTS OF THE PERIODIC REEXAMINATION REPORT ................................................. 4 2.0 MAJOR PROBLEMS AND OBJECTIVES IN 1988 AND 2003 .............................................................. 4 3.0 EXTENT TO WHICH SUCH PROBLEMS AND OBJECTIVES HAVE BEEN REDUCED OR INCREASED ................................................................................................................................................................. 7 1988 Master Plan ...................................................................................................................................................... 7 2003 Master Plan Reexamination Report ................................................................................................... 10 4.0 EXTENT TO WHICH THERE HAVE BEEN SIGNIFICANT CHANGES IN THE ASSUMPTIONS, POLICIES AND OBJECTIVES ............................................................................................................................. -

Adaptation to the Impacts of Sea‐Level Rise at the Monmouth County Raritan Bayshore

Adaptation to the Impacts of Sea‐Level Rise at the Monmouth County Raritan Bayshore Developed in partnership with the Jacques Cousteau National Estuarine Research Reserve‐Rutgers University, Sandy Hook Unit, Gateway National recreation Area‐National Park Service, and the American Littoral Society June 4, 2009 Adaptation to the Impacts of Sea‐Level Rise at the Monmouth County Raritan June 4, Bayshore 2009 Table of Contents Issue/Background 1 Workshop Objective 1 Workshop Summary 2 Agenda 5 Workshop Participants 6 More Information Coastal Resources 7 GIS Resources 7 Workshop Presenters 8 Adaptation to the Impacts of Sea‐Level Rise at the Monmouth County Raritan June 4, Bayshore 2009 Issue/Background The impacts of global warming and sea‐level rise are currently affecting many elements of the Monmouth County Raritan Bayshore communities. The Raritan Bayshore is home to over 120,000 residents and is situated in the northern region of Monmouth County, NJ. The ecological area is a mix of developed community, wetlands, micro‐estuaries, and beach systems. Because the area is relatively close to local mean sea level, flooding is common during storm events. The erosion of the estuarine beaches and dunes, along with absolute sea‐level rise, impacts the built and the natural environment. The projected climate change impacts for coastal regions are an increased rate of sea‐level rise, displacement of natural features related to a sea‐level position, increased frequency of flooding of low‐ lying, fixed infrastructure, and increased vulnerability to inundation caused by storms. These coastal changes are impacting the vital marine resources and coastal ecosystems, as well as posing potential damage to building, business, and infrastructure. -

Keansburg, East Keansburg and Laurence Harbor, New

/ 1 171749 RARITAN BAY AND SANDY HOOK BAY, NEW JERSEY FEASIBILITY REPORT FOR HURRICANE AND STORM DAMAGE REDUCTION Keansburg, East Keansburg, and Laurence Harbor, New Jersey Draft Reevaluation Report Beach Fill Renourishment (Section 506 of WRDA 1996) Volume 2: Draft Environmental Assessment and Environmental Appendices |"C3"1 US Army Corps of Engineers New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection New York District November 2007 RARITAN BAY AND SANDY HOOK BAY HURRICANE AND STORM DAMAGE REDUCTION STUDY KEANSBURG, EAST KEANSBURG, AND LAURENCE HARBOR, NEW JERSEY DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT Laurence Harbor , Project Area j NOVEMBER 2007 Prepared by: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers New York District 26 Federal Plaza New York, New York 10278-0090 DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT RARITAN BAY AND SANDY HOOK BAY HURRICANE AND STORM DAMAGE REDUCTION STUDY KEANSBURG, EAST KEANSBURG, AND LAURENCE HARBOR, NEW JERSEY November 2007 Prepared By: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers New York District 26 Federal Plaza New York, NY 10278-0090 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Raritan Bay and Sandy Hook Bay Hurricane and Storm Damage Reduction Study Keansburg, East Keansburg, and Laurence Harbor, New Jersey The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), New York District (District), is currently evaluating the feasibility to provide beach renourishment to restore a previously authorized and constructed shore and hurricane protection to residential, commercial, and recreational resources in the Borough of Keansburg and the East Keansburg community of Middletown Township, Monmouth County, and the Laurence Harbor area of Old Bridge Township, Middlesex County, New Jersey (Study Area). Hurricanes, northeasters,, and extratropical storms have historically damaged homes, roads, commercial structures, shorefronts, beaches, and dunes throughout the Raritan Bay and Sandy Hook Bay (RBSHB) shore area. -

Science Challenge Bayshore School Plans Go to State Enrollm Ent So Far Is on Target

IN THIS ISSUE IN THE NEWS Giants Home & slam dunk Garden SERVING ABERDEEN, HAZLET, HOLMDEL, for kids _:_____ i_______ KEYPORT, MATAWAN AND MIDDLETOWN Page 29 Page 3 MARCH 11, 1998 ____________________________________ 40 CENTS____________________________________VOLUME 28, NUMBER 10 Science challenge Bayshore School plans go to state Work on middle The Township Committee held a public hearing last week and voted to vacate a por school expansion tion of Leonard Avenue to make room for to begin in May the Bayshore Middle School expansion. According to Middletown Planning _______ BY MARY DEMPSEY________ Board Director Tony Mercantante, the roadway will be used for parking and a bus Staff W riter drop-off area. fter a heated debate between board The portion of the road that will be members over access to informa closed is between the school and a field, he A tion, the Middletown Board of said. There is little or no traffic there right Education Thursday approved the now,sub he said, adding that only one house on mission of the final review plans for Bay that portion of the road will be affected. shore Middle School to the state Depart The motion to submit Bayshore’s final ments of Education and Community Affairs. review plans was made by board member The plans are part of the $78.4 million N. Britt Raynor, who is also a member of referendum passed in December 1996 which the board’s facilities committee overseeing included renovations and additions to the the referendum project. district’s three middle schools, Bayshore, Board President Robert Bucco and Leonardville Road, Thompson, Middle- members Richard Kilar and John Johnson town-Lincrofi Road, and Thome, Harmony make up the remaining members of the Road, and two high schools, North, Tindall facilities committee. -

Hudson-Raritan Estuary Comprehensive Restoration Plan

Hudson-Raritan Estuary Comprehensive Restoration Plan Version 1.0 Volume I June 2016 and In partnership with Contributing Organizations Government • Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies • U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, New York District • City University of New York • The Port Authority of New York & New Jersey • Cornell University • National Park Service • Dowling College • National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration • Harbor School • U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources • Hudson River Foundation Conservation Service • Hunter College • U.S. Environmental Protection Agency • Kean University • U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service • Liberty Science Center • Empire State Development Corporation • Manhattan College • New Jersey Department of Environmental • Montclair State University Protection, Division of Fish and Wildlife • New Jersey City University • New Jersey Department of Transportation • New Jersey Marine Science Consortium • New Jersey Meadowlands Commission • New York-New Jersey Harbor & Estuary Program • New York State Department of Environmental • Queens College Conservation • Rutgers University and Institute of Marine and • New York State Department of State, Division of Coastal Sciences Coastal Resources • State University of New York at Stony Brook • New York City Mayor’s Office • State University of New York – College of • New York City Department of Parks and Recreation Environmental Science and Forestry • New York City Department of Environmental • Stevens Institute of Technology Protection • St. John’s University