National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Casting the Buffalo Commons: a Rhetorical Analysis of Print Media Coverage of the Buffalo Commons Proposal for the Great Plains

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for May 2002 CASTING THE BUFFALO COMMONS: A RHETORICAL ANALYSIS OF PRINT MEDIA COVERAGE OF THE BUFFALO COMMONS PROPOSAL FOR THE GREAT PLAINS Mary L. Umberger Metropolitan Community College in Omaha Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Umberger, Mary L., "CASTING THE BUFFALO COMMONS: A RHETORICAL ANALYSIS OF PRINT MEDIA COVERAGE OF THE BUFFALO COMMONS PROPOSAL FOR THE GREAT PLAINS" (2002). Great Plains Quarterly. 50. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/50 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in Great Plains Quarterly, vol. 22, no. 2 (Spring 2002). Published by the Center for Great Plains Studies, University of Nebraska–Lincoln. Copyright © 2000 Center for Great Plains Studies. Used by permission. CASTING THE BUFFALO COMMONS A RHETORICAL ANALYSIS OF PRINT MEDIA COVERAGE OF THE BUFFALO COMMONS PROPOSAL FOR THE GREAT PLAINS MARY L. UMBERGER They filed into the auditorium and found "I live on this land," one audience member seats, waiting politely for what they expected snorted. "My granddad lived on this land. You to be a preposterous talk. The featured speaker want me to reserve it for a herd of buffalo and rose and began his prepared speech. The audi- some tourists?" ence took note of his attire, his educated vo- But the challenges muted as the overhead cabulary, his "eastern" ways. -

Final Environmental Impact Statement Campbell, Converse, Niobrara and Weston Counties, Wyoming

Final United States Department of Agriculture Environmental Impact Forest Service Statement October, 2009 Thunder Basin National Grassland Prairie Dog Management Strategy and Land and Resource Management Plan Amendment #3 Douglas Ranger District, Medicine Bow-Routt National Forests and Thunder Basin National Grassland Campbell, Converse, Niobrara and Weston Counties, Wyoming Environmental Impact Statement Prairie Dog Plan Amendment FINAL The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individuals income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA's TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, DC 20250-9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. 2 Thunder Basin National Grassland Prairie Dog Management Strategy and Land and Resource Management Plan Amendment #3 Final Environmental Impact Statement Campbell, Converse, Niobrara and Weston Counties, Wyoming Lead Agency: USDA Forest Service Responsible Official: MARY H. PETERSON, FOREST SUPERVISOR 2468 Jackson Street Laramie, Wyoming 82701 For Information Contact: MISTY A. HAYS, DEPUTY DISTRICT RANGER 2250 East Richards Street Douglas, WY 82633 307-358-4690 Abstract: The Forest Service proposes to amend the Thunder Basin Land and Resource Management Plan (LRMP) as needed to support implementation of an updated strategy to manage black-tailed prairie dogs on Thunder Basin National Grassland (TBNG). -

Download (Pdf)

THE PHYSICAL FEATURES OF THE UNITED STATES. BY PROF. J. D. WHITNEY, CAMBRIDGE, MASS. N describing the physical Features oF a country, we have First to consider the skeleton The Rocky Mountains proper, with their continuations southward in New Mexico, or frame-work oF mountains to which its plains, valleys, and river system are subor Form the north and south trending portions oF the eastern rim oF the Cordilleras, and in I dinate, and on the direction and elevation oF whose parts its climate is in a very latitude 430, nearly, the change From a northern to a northwestern direction oF the ranges large degree dependent takes place, the Big Horn, Wind River, Bitter Root, and other subordinate ranges oF which The skeleton oF the United States is represented by two great systems oF mountain the chain is here made up, having the same northwesterly trend as the Sierra Nevada. ranges, or combinations oF ranges— one forming the eastern, the other the western, side oF The lozenge-shaped figure thus indicated, framed in, as it were, by the Cascade range the frame-work by which the central portion oF our continent is embraced. These two and Sierra Nevada on the west, and the Rocky Mountains on the east, encloses a high systems are the Appalachian ranges and the Cordilleras.* These systems are oF very plateau, which, through its centre, east and west, has an elevation oF From 4,000 to 5,000 Feet diFferent magnitude and extent above the sea-level, and which Falls oFF in height toward the north and south From that The Cordilleras are a part oF the great system or chain oF mountains which borders central line. -

Spring Births at the Jackson Zoo

NEWS Date: April 12, 2007 Contact: Christopher Mims, Director of Marketing and Public Relations 601-352-2599 Spring Births at the Jackson Zoo Dama Gazelle The Jackson Zoo is pleased to announce the birth of Gumby born last week to parents Valkyrie and Fireball. The baby Dama Gazelle is fitting in nicely in African Savannah exhibit. This is Valkyrie’s third offspring. The Dama Gazelle weighs up to 190 lbs. and stands up to 42” tall at the shoulder. It is found in the Sahara Desert and the Sahel. While avoiding mountains and dunes, it favors stony plains and plateaus, inter-dunal depressions with shallow sandy soils, and undulating foothills and steppes. The Dama Gazelle is highly drought resistant - most of its water is obtained from its plant food. It browses on various desert shrubs and acacias, and it eats rough desert grasses in times of drought. Dama Gazelle s move into the Sahara in the wet season and out of the Sahara (both to the north and to the south) to moister parts of their range for the dry season. The social organization of Dama Gazelle s is greatly affected by the seasons. Herds typically spend the dry season in the Sahel where they occur singly or in mixed groups of 10 - 15. With the onset of the rainy season, they migrate into the desert and can be found in aggregations which, in the past, included up to several hundred males and females. Gumby rests near a log in her exhibit. The Dama Gazelle was once one of the most numerous and widespread of Saharan gazelles from Morocco, Senegal and Mauritania eastward to the Sudan. -

Book Reviews

East Texas Historical Journal Volume 12 Issue 1 Article 11 3-1974 Book Reviews Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation (1974) "Book Reviews," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 12 : Iss. 1 , Article 11. Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol12/iss1/11 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the History at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 56 EAST TEXAS HISTORICAL JOURNAL BOOK REVIEWS .. The French Legation in Texas, Volume II. By Nancy Nichols Barker (translator and editor). Austin (The Texas State Historical Association), 1973. Pp. 369-710. Illust rations, calendar, index. $12.00. The second volume of the letters from the French charge d'affaires to his superiors is as pleasing as the first to students of the Texas Republic. Translator Nancy Nichols Barker has made the impartial, accurate reports of Viscount Jules de Cramayel and the more colorful despatches of Alphonse Dubois de Saligny readily available to researchers by providing full translations of material where the two men had personal contact with officials of the Texas government. Elsewhere the editor offers brief sum maries of the deleted matter and refers those who wish to read the omitted portions to the Austin Public Library where the entire collection is on microfilm. She also has included all of the instructions to the charge that have been preserved in the archives of the French foreign ministry, along with other pertinent documents discovered there. -

WASTED in the LONE STAR STATE the Impacts of Toxic Oil and Gas Waste in Texas April 2021

Farmington WASTED IN THE LONE STAR STATE The impacts of toxic oil and gas waste in Texas April 2021 TEXAS OIL AND GAS WASTE REPORT The failure to safely manage oil and gas waste 1 earthworks.org/wasted-in-TX Farmington WASTED IN THE LONE STAR STATE The impacts of toxic oil and gas waste in Texas April 2021 AUTHORS: Melissa Troutman and Amy Mall for Earthworks Special thanks to FracTracker Alliance, Erica Jackson, Lone Star Chapter Sierra Club, and Emma Pabst for their contributions to this report and continued support of frontline communities. Outside cover photos: Drilling rig by Jim/Adobe Stock; spill and piping by Earthworks. Inside cover photo by Алексей Закиров/Adobe Stock. Design by CreativeGeckos.com EARTHWORKS Offices in California, Colorado, Maine, Maryland, Minnesota, Montana, New Mexico, New York, Pennsylvania, Texas, West Virginia EARTHWORKS • 1612 K St., NW, Suite 904 Washington, D.C., USA 20006 www.earthworks.org • Report at https://earthworks.org/wasted-in-TX Dedicated to protecting communities and the environment from the adverse impacts of mineral and energy development while promoting sustainable TEXAS OIL AND GAS WASTE REPORT The failure to safely managesolutions. oil and gas waste 2 earthworks.org/wasted-in-TX TEXAS OIL AND GAS WASTE REPORT—April 2021 Table of Contents Executive Summary ..........................................................................................................4 Introduction .......................................................................................................................5 -

Final Report of the Commission on Historic Campus Representations

BAYLOR UNIVERSITY Commission on Historic Campus Representations FINAL REPORT Prepared for the Baylor University Board of Regents and Administration December 2020 Table of Contents 3 Foreword 5 Introduction 9 Part 1 - Founders Mall Founders Mall Historic Representations Commission Assessment and Recommendations 31 Part 2 - Burleson Quadrangle Burleson Quadrangle Historic Representations Commission Assessment and Recommendations 53 Part 3 - Windmill Hill and Academy Hill at Independence Windmill Hill and Academy Hill Historic Representations Commission Assessment and Recommendations 65 Part 4 - Miscellaneous Historic Representations Mace, Founders Medal, and Mayborn Museum Exhibit Commission Assessment and Recommendations 74 Appendix 1 76 Appendix 2 81 Appendix 3 82 Endnotes COMMISSION ON HISTORIC CAMPUS REPRESENTATIONS I 1 Commission on Historic Campus Representations COMMISSION CO-CHAIRS Cheryl Gochis (B.A. ’91, M.A. Michael Parrish, Ph.D. (B.A. ’74, ’94), Vice President, Human M.A. ’76), Linden G. Bowers Alicia D.H. Monroe, M.D., Resources/Chief Human Professor of American History Provost and Senior Vice Resources Officer President for Academic and Coretta Pittman, Ph.D., Faculty Affairs, Baylor College of Dominque Hill, Director of Associate Professor of English Medicine and member, Baylor Wellness and Past-President, and Chair-Elect, Faculty Senate Board of Regents Black Faculty and Staff Mia Moody-Ramirez, Ph.D. Association Gary Mortenson, D.M.A., (M.S.Ed. ’98, M.A. ’01), Professor and Dean, Baylor Sutton Houser, Senior, Student Professor and Chair, Journalism, University School of Music Body President Public Relations and New Media Walter Abercrombie (B.S. ’82, Trent Hughes (B.A. ’98), Vice Marcus Sedberry, Senior M.S.Ed. -

WILLIAM CAREY CRANE, III 32604 Bell Road “Tippitt's Hill” Round Hill, VA 20141

WILLIAM CAREY CRANE, III 32604 Bell Road “Tippitt's Hill” Round Hill, VA 20141 PERSONAL Born - May 11, 1953 Married to the former Teresa Yancey Two children - Judson and Sarah EDUCATION Northeastern University Ohio Wesleyan University of Connecticut, Business Administration EMPLOYMENT LOCHNAU, INC. - 1988 - to present (An Asset & Financial Management Company) President - 1998 BRANE-STROM, LP - 1987 to present General Partner FIBERGLASS UNLIMITED, INC. - 1983-1987 Stamford, Connecticut President - Products ranging from Dinghies to Contour Terrain maps for helicopter simulators. FUTURE SOUND, INC. - 1978- 1983 Westport, Connecticut Partner - Designed and installed public address systems using revolutionary Soundsphere Loud Speakers. Racetracks and coliseums primarily, including all venues at the 1980 Winter Olympics at Lake Placid and opening ceremonies at the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles. SONIC SYSTEMS, INC. - 1976 - 1978 Stamford, Connecticut Product Manager - In charge of new product development. Designed entire manufacturing process including all casting. Page Two DIRECTORSHIPS ALLIANCE FOR ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION - 1989 to 1996. Marshall, Virginia The Alliance is made up of 250 organizations ranging from corporate, NGO, Educator and individuals. The mission is to improve global environmental understanding and quality by supporting environmental education and training initiatives through the development and management of the Network for Environmental Education. VIRGINIA RECREATIONAL FACILITIES AUTHORITY - 1989 - 1994. Roanoke, -

Baylor News December 1998

President’s December Academic Last Perspective Focus Agenda Glance Public television: Best of both worlds: Dying of the Light: Backyard Monsters: Baylor acquires KCTF to Institute finding ways to Burtchaell’s book con- The Junior League and Baylor provide learning laboratory, integrate intellectual tends Christian universi- combine efforts to support new local programming. pursuit2 with Christian faith.3 ties unfaithful3 to purpose.5 children’s museum at complex. 2 Vol. 8, No. 10 • DECEMBER8 1998 Institute for Faith and Learning Year-old center seeks ways to have faith informed by best of learning and learning informed by best of faith By Julie Carlson s the millennium approaches, organizations throughout the world will examine their tradi- A tions and missions. Baylor is no exception, and one of the most important issues the University must face is how to achieve prominence in the world of higher education while remaining true to its Baptist heritage. It is a question that sparks disagree- ment from external constituents and within Baylor itself (see this month’s “Academic Agenda,” page 5). A survey of Baylor faculty conducted in 1995 by Dr. Larry Lyon, dean of the graduate school and professor of sociology, and Dr. Michael Beaty, director of the Institute for Faith and Learning and associate professor of philosophy, highlighted the fact that even among Baylor faculty, the intersection between faith and learning is unclear. Dr. Lyon and Dr. Beaty found that while 92 percent of faculty surveyed “create a syllabus for a course that includes a Dr. Beaty, the formal establishment of the believe “it is possible for Baylor to achieve clear, academically legitimate Christian per- Institute was the culmination of years of re- academic excellence and maintain a Christian spective on the subject.” search. -

Bu-Etd-The-Williams 1941-07.Pdf (19.23Mb)

HISTORY OF BAYLOR A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE OF HISTORY AMD THE GRADUATE OF BAYLOR IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS BY EARL FRANCIS JULY 1941 Approved the Department (Signed) Head of the Department of (Signed) Chairma 6f t] Graduate Council Date . 1 i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. The Movement for Higher Education in Texas 5 II. Baylor University at Years III. Baylor University at Independence Under C. E9 Waco University 48 V. Closing Years of Baylor University at Independence 60 The Consolidation of Baylor University and Waco University 78 Baylor University, 1886-1902 95 7III. The Administration of President Brooks. IX. The Administration of Pat M. 1E8 X. Contributions of Baylor University. 138 Conclusion 153 Bibliography 154 PREFACE This thesis has been for tnose love Baylor and wish to know the rich history of the "grand old school." The purpose has been to show the development of the institution from its beginning in the days of the Republic of Texas to the present-day Baylor University whose influence extends to many parts of the In tracing this history, it was necessary to show Texas as it was prior to the year 1845 and that in these early years of Texas, a movement for higher education was slowly but surely gathering force. Many prominent Baptists were the leaders in this movement, led to the founding of Baylor University at Independence. This same desire to provide an opportunity for higher education led to the founding of the institution which was later to become Waco University and then Baylor University at Baylor University at Independence passed there was left an influence that is still felt in the lives of the hundreds of students who continue to pass through the portals of Baylor University at An effort has been made to portray the life and spirit of Baylor University and to show how the ideals of those leaders who made Baylor University possible are still evident in the life and traditions of the institution and are molding the aims and ambitions of the students of Baylor of the present day. -

Baptist Periodicals in Alabama, 1835-1873 F

BAPTIST PERIODICALS IN ALABAMA, 1835-1873 F. Wilbur Helmbold* The published sources of denominational news, as well as the discussion of theological and moral issues, which were available to Alabama Baptists in the pioneer period and until the middle of the 1830's were in the Baptist newspapers in the older states from whence the people had migrated to the new country. Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina and Virginia all had Baptist periodicals which were known to the Baptists who moved to Alabama. The rising controversy over the missionary question was a contributing cause for the establishment of at least two anti-missionary (Old School, or Primitive) Baptist publications which also had some Alabama contacts. Signs of the Times, begun in 1832 by Gilbert Beebe in New-Vernon, N. Y., moved to Alexandria, Va., and back again to New York, was highly critical of the missionary movement and of the periodicals published by the missionary brethren. In 1835 and 1837, Beebe published letters from Alabama Baptists of the Primitive persuasion which reported on the situation in the state. It is quite likely that similar communications from Alabama correspondents were published in the Primitive Baptist, which was issued at Tarboro, N. C., beginning in 1835 under the editorship first of Elder Burwell Temples and the soon Elder Mark Bennett. 1 It was not until 1835 that the first known Baptist periodical was begun in Alabama, when Rev. William Wood established the Jacksonville Register at Jacksonville, Alabama. It ceased publication in 1836, being the first in a succession of Alabama Baptist periodicals which struggled only briefly and then succumbed because of inadequate support. -

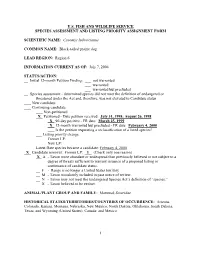

2004 Species Assessment and Listing Priority Assignment Form

U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE SPECIES ASSESSMENT AND LISTING PRIORITY ASSIGNMENT FORM SCIENTIFIC NAME: Cynomys ludovicianus COMMON NAME: Black-tailed prairie dog LEAD REGION: Region 6 INFORMATION CURRENT AS OF: July 7, 2004 STATUS/ACTION: Initial 12-month Petition Finding: ___ not warranted ___ warranted ___ warranted but precluded Species assessment - determined species did not meet the definition of endangered or threatened under the Act and, therefore, was not elevated to Candidate status New candidate Continuing candidate Non-petitioned X Petitioned - Date petition received: July 31, 1998; August 26, 1998 X 90-day positive - FR date: March 25, 1999 X 12-month warranted but precluded - FR date: February 4, 2000 Is the petition requesting a reclassification of a listed species? Listing priority change Former LP: New LP: Latest Date species became a candidate: February 4, 2000 X Candidate removal: Former LP: 8 (Check only one reason) X A - Taxon more abundant or widespread than previously believed or not subject to a degree of threats sufficient to warrant issuance of a proposed listing or continuance of candidate status. F - Range is no longer a United States territory M - Taxon mistakenly included in past notice of review. N - Taxon may not meet the Endangered Species Act’s definition of “species.” X - Taxon believed to be extinct. ANIMAL/PLANT GROUP AND FAMILY: Mammal, Sciuridae HISTORICAL STATES/TERRITORIES/COUNTRIES OF OCCURRENCE: Arizona, Colorado, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Texas, and Wyoming (United States); Canada; and Mexico 1 CURRENT STATES/COUNTIES/TERRITORIES/COUNTRIES OF OCCURRENCE: Colorado, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Texas, and Wyoming (United States); Canada; and Mexico LEAD REGION CONTACT: Seth Willey, (303) 236-4257 LEAD FIELD OFFICE CONTACT: Pete Gober, (605) 224-8693, extension 24 INTRODUCTION: On July 31, 1998, the U.S.