Evaluation of the Cheshire and Merseyside Drink Less Enjoy More Intervention

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Radio City 2 and City Talk Requests to Change Formats

Radio City 2 and City Talk Requests to change Formats Consultation Publication date: 21 July 2015 Closing date for responses: 2 September 2015 Requests to change Formats – Radio City 2 and City Talk Contents Section Page 1 About this document 2 2 Details and background information 3 Annex Page 1 Responding to this consultation 6 2 Ofcom’s consultation principles 8 3 Consultation response cover sheet 9 4 Consultation questions 11 5 Format Change Requests - Radio City 2 & City Talk 22 6 Existing Formats of Radio City & City Talk 23 7 Other commercial and community radio stations in the Liverpool area 24 1 Requests to change Formats – Radio City and City Talk Section 1 1 About this document 1.1 Ofcom has received two Format change requests from Radio City (Sound of Merseyside) Ltd, which holds an AM and two FM commercial radio licences for Liverpool. 1.2 A station’s Format describes the type of programme service which it is required to provide, and forms part of the station’s licence. 1.3 Radio City (Sound of Merseyside) Ltd wishes to change the ‘Character of Service’ of its AM licence (currently Radio City 2) and one of its FM licences (currently City Talk). 1.4 Radio City 2’s published Format requires the service to broadcast “a classic soft pop music-led service”. The licensee wishes to change this to a service of “rock hits with news, local sport and information programming.” 1.5 City Talk’s published Format requires the service to broadcast “speech and soft pop- led music programming”. -

Pocketbook for You, in Any Print Style: Including Updated and Filtered Data, However You Want It

Hello Since 1994, Media UK - www.mediauk.com - has contained a full media directory. We now contain media news from over 50 sources, RAJAR and playlist information, the industry's widest selection of radio jobs, and much more - and it's all free. From our directory, we're proud to be able to produce a new edition of the Radio Pocket Book. We've based this on the Radio Authority version that was available when we launched 17 years ago. We hope you find it useful. Enjoy this return of an old favourite: and set mediauk.com on your browser favourites list. James Cridland Managing Director Media UK First published in Great Britain in September 2011 Copyright © 1994-2011 Not At All Bad Ltd. All Rights Reserved. mediauk.com/terms This edition produced October 18, 2011 Set in Book Antiqua Printed on dead trees Published by Not At All Bad Ltd (t/a Media UK) Registered in England, No 6312072 Registered Office (not for correspondence): 96a Curtain Road, London EC2A 3AA 020 7100 1811 [email protected] @mediauk www.mediauk.com Foreword In 1975, when I was 13, I wrote to the IBA to ask for a copy of their latest publication grandly titled Transmitting stations: a Pocket Guide. The year before I had listened with excitement to the launch of our local commercial station, Liverpool's Radio City, and wanted to find out what other stations I might be able to pick up. In those days the Guide covered TV as well as radio, which could only manage to fill two pages – but then there were only 19 “ILR” stations. -

46082 Hospital Radio On

FRONT COVER DOCUMENT 123: FRONT COVER DOCUMENT 123 29/7/08 02:49 Page 1 IFC Autumn conference: IFC Autumn conference 29/7/08 02:51 Page 1 The Last Autumn Conference ... Ever This is your chance to be present when history is made. Due to changes taking place within the HBA, the HBA Executive have decided not to hold any more Autumn conference so the last one will be held 10th-12th October 2008 at the four star St Johns Hotel (formerly the Marriott Renaissance) in Solihull. The first Autumn Conference was held at Durham in 1970 ... thirty eight years ago. The last will be at Solihull from 10th – 12th October 2008. The hotel is five miles from Birmingham International Airport and Rail station and is less than two miles from the M42 motorway. Birmingham City Centre is eight miles away and for chocolate lovers, Cadbury World is just six miles away. The hotel has all the facilities you would expect from a modern four star hotel, including a leisure centre with a swimming pool and a whirlpool/jacuzzi/hot tub. You can find more details of the hotel at: http://www.principal-haley.com/birmingham/the-st-johns-hotel/index.asp We have a full programme of seminars and visits planned plus the AGM and an after dinner speaker for Saturday night. All this can be yours for just £135. There are NO single room supplements. You can download a booking form from the HBA website www.hbauk.com or if you prefer, call or e-mail Marie Harper on 0870 321 6017 [email protected] 01 INTRO 123:01 INTRO 123 29/7/08 03:57 Page 1 July/August 2008 Issue 123 The Official Journal of the Hospital Broadcasting Association Hi Everyone, My sincere thanks to everyone who has taken the trouble to in this issue .. -

Hallett Arendt Rajar Topline Results - Wave 3 2019/Last Published Data

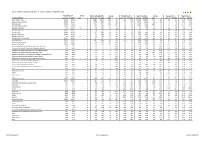

HALLETT ARENDT RAJAR TOPLINE RESULTS - WAVE 3 2019/LAST PUBLISHED DATA Population 15+ Change Weekly Reach 000's Change Weekly Reach % Total Hours 000's Change Average Hours Market Share STATION/GROUP Last Pub W3 2019 000's % Last Pub W3 2019 000's % Last Pub W3 2019 Last Pub W3 2019 000's % Last Pub W3 2019 Last Pub W3 2019 Bauer Radio - Total 55032 55032 0 0% 18083 18371 288 2% 33% 33% 156216 158995 2779 2% 8.6 8.7 15.3% 15.9% Absolute Radio Network 55032 55032 0 0% 4743 4921 178 4% 9% 9% 35474 35522 48 0% 7.5 7.2 3.5% 3.6% Absolute Radio 55032 55032 0 0% 2151 2447 296 14% 4% 4% 16402 17626 1224 7% 7.6 7.2 1.6% 1.8% Absolute Radio (London) 12260 12260 0 0% 729 821 92 13% 6% 7% 4279 4370 91 2% 5.9 5.3 2.1% 2.2% Absolute Radio 60s n/p 55032 n/a n/a n/p 125 n/a n/a n/p *% n/p 298 n/a n/a n/p 2.4 n/p *% Absolute Radio 70s 55032 55032 0 0% 206 208 2 1% *% *% 699 712 13 2% 3.4 3.4 0.1% 0.1% Absolute 80s 55032 55032 0 0% 1779 1824 45 3% 3% 3% 9294 9435 141 2% 5.2 5.2 0.9% 1.0% Absolute Radio 90s 55032 55032 0 0% 907 856 -51 -6% 2% 2% 4008 3661 -347 -9% 4.4 4.3 0.4% 0.4% Absolute Radio 00s n/p 55032 n/a n/a n/p 209 n/a n/a n/p *% n/p 540 n/a n/a n/p 2.6 n/p 0.1% Absolute Radio Classic Rock 55032 55032 0 0% 741 721 -20 -3% 1% 1% 3438 3703 265 8% 4.6 5.1 0.3% 0.4% Hits Radio Brand 55032 55032 0 0% 6491 6684 193 3% 12% 12% 53184 54489 1305 2% 8.2 8.2 5.2% 5.5% Greatest Hits Network 55032 55032 0 0% 1103 1209 106 10% 2% 2% 8070 8435 365 5% 7.3 7.0 0.8% 0.8% Greatest Hits Radio 55032 55032 0 0% 715 818 103 14% 1% 1% 5281 5870 589 11% 7.4 7.2 0.5% -

Bauer Media Group Phase 1 Decision

Completed acquisitions by Bauer Media Group of certain businesses of Celador Entertainment Limited, Lincs FM Group Limited and Wireless Group Limited, as well as the entire business of UKRD Group Limited Decision on relevant merger situation and substantial lessening of competition ME/6809/19; ME/6810/19; ME/6811/19; and ME/6812/19 The CMA’s decision on reference under section 22(1) of the Enterprise Act 2002 given on 24 July 2019. Full text of the decision published on 30 August 2019. Please note that [] indicates figures or text which have been deleted or replaced in ranges at the request of the parties or third parties for reasons of commercial confidentiality. SUMMARY 1. Between 31 January 2019 and 31 March 2019 Heinrich Bauer Verlag KG (trading as Bauer Media Group (Bauer)), through subsidiaries, bought: (a) From Celador Entertainment Limited (Celador), 16 local radio stations and associated local FM radio licences (the Celador Acquisition); (b) From Lincs FM Group Limited (Lincs), nine local radio stations and associated local FM radio licences, a [] interest in an additional local radio station and associated licences, and interests in the Lincolnshire [] and Suffolk [] digital multiplexes (the Lincs Acquisition); (c) From The Wireless Group Limited (Wireless), 12 local radio stations and associated local FM radio licences, as well as digital multiplexes in Stoke, Swansea and Bradford (the Wireless Acquisition); and (d) The entire issued share capital of UKRD Group Limited (UKRD) and all of UKRD’s assets, namely ten local radio stations and the associated local 1 FM radio licences, interests in local multiplexes, and UKRD’s 50% interest in First Radio Sales (FRS) (the UKRD Acquisition). -

Performing Right Society Limited Distribution Rules

PERFORMING RIGHT SOCIETY LIMITED DISTRIBUTION RULES PRS distribution policy rules Contents INTRODUCTION...................................................................................... 12 Scope of the PRS Distribution Policy ................................................................................ 12 General distribution policy principles ............................................................................. 12 Policy review and decision-making processes ............................................................. 13 DISTRIBUTION CYCLES AND CONCEPTS ................................................. 15 Standard distribution cycles and frequency .................................................................. 15 Distribution basis ..................................................................................................................... 15 Distribution sections ............................................................................................................... 16 Non-licence revenue ............................................................................................................... 16 Administration recovery rates ............................................................................................ 16 Donation to the PRS Foundation and Members Benevolent Fund ........................ 17 Weightings .................................................................................................................................. 17 Points and point values ......................................................................................................... -

Domain Stationid Station UDC Performance Date Number of Days

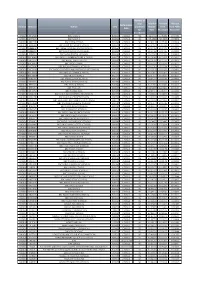

Number of days Total Per Amount Amount Performance Domain StationId Station UDC processed Minute from from Public Date for Rate Broadcast Reception distribution RADIO BR ONE BBC RADIO 1 B0001 CENSUS 92 £12.2471 £7.3036 £4.9435 RADIO BR TWO BBC RADIO 2 B0002 CENSUS 92 £25.4860 £25.3998 £0.0862 RADIO BR1EXT BBC 1XTRA CENSUS B0106 CENSUS 92 £2.8113 £2.7199 £0.0914 RADIO BRASIA BBC ASIAN NETWORK (CENSUS) B0064 CENSUS 92 £3.6951 £3.3058 £0.3892 RADIO BRBEDS BBC THREE COUNTIES RADIO (CENSUS) B0065 CENSUS 92 £0.2445 £0.2442 £0.0003 RADIO BRBERK BBC RADIO BERKSHIRE (CENSUS) B0103 CENSUS 92 £0.1436 £0.1435 £0.0002 RADIO BRBRIS BBC RADIO BRISTOL (CENSUS) B0066 CENSUS 92 £0.1532 £0.1531 £0.0002 RADIO BRCAMB BBC RADIO CAMBRIDGESHIRE (CENSUS) B0067 CENSUS 92 £0.1494 £0.1493 £0.0002 RADIO BRCLEV BBC RADIO TEES (CENSUS) B0068 CENSUS 92 £0.1478 £0.1477 £0.0002 RADIO BRCMRU BBC RADIO CYMRU B0011 CENSUS 92 £0.5707 £0.5690 £0.0017 RADIO BRCORN BBC RADIO CORNWALL (CENSUS) B0069 CENSUS 92 £0.1535 £0.1534 £0.0002 RADIO BRCOVN BBC RADIO COVENTRY AND WATWICKSHIRE(CENSUS) B0070 CENSUS 92 £0.1023 £0.1022 £0.0001 RADIO BRCUMB BBC RADIO CUMBRIA (CENSUS) B0071 CENSUS 92 £0.1085 £0.1084 £0.0001 RADIO BRCYMM BBC RADIO CYMRU 2 B0114 CENSUS 92 £0.5707 £0.5690 £0.0017 RADIO BRDEVN BBC RADIO DEVON (CENSUS) B0072 CENSUS 92 £0.2421 £0.2419 £0.0003 RADIO BRDRBY BBC RADIO DERBY (CENSUS) B0073 CENSUS 92 £0.1535 £0.1534 £0.0002 RADIO BRESSX BBC ESSEX (CENSUS) B0074 CENSUS 92 £0.2091 £0.2089 £0.0002 RADIO BRFIVE BBC FIVE LIVE B0005 CENSUS 92 £10.0855 £10.0811 £0.0044 RADIO BRFOYL -

“Reaching 79% of Commercial Radio's Weekly Listeners…” National Coverage

2019 GTN UK is the British division of Global Traffic Network; the leading provider of custom traffic reports to commercial radio and television stations. GTN has similar operations in Australia, Brazil and Canada. GTN is the largest Independent radio network in the UK We offer advertisers access to over 240 radio stations across the country, covering every major conurbation with a solus opportunity enabling your brand to stand out with up to 48% higher ad recall than that of a standard ad break. With both a Traffic & Travel offering, as well as an Entertainment News package, we reach over 28 million adults each week, 80% of all commercial radio’s listeners, during peak listening times only, 0530- 0000. Are your brands global? So are we. Talk to us about a global partnership. Source: Clark Chapman research 2017 RADIO “REACHING 79% OF COMMERCIAL RADIO’S WEEKLY LISTENERS…” NATIONAL COVERAGE 240 radio stations across the UK covering all major conurbations REACH & FREQUENCY Reaching 28 million adults each week, 620 ratings. That’s 79% of commercial radio’s weekly listening. HIGHER ENGAGEMENT With 48% higher ad recall this is the stand-out your brand needs, directly next to “appointment-to-listen” content. BREAKFAST, MORNING, AFTERNOON, DRIVE All advertising is positioned within key radio listening times for maximum reach. 48% HIGHER AD RECALL THAN THAT OF A STANDARD AD BREAK Source: Clark Chapman research NATIONAL/DIGITAL LONDON NORTH EAST Absolute Radio Absolute Radio Capital North East Absolute Radio 70s Kiss Classic FM (North) Absolute -

Advisory Group on Media Mergers Report 2008

ADVISORY GROUP ON MEDIA MERGERS Report to the Tánaiste and Minister for Enterprise, Trade and Employment, Mary Coughlan T.D. June 2008 1 1. Chapter 1- Introduction INTRODUCTION TO REPORT 1.1 In March of 2008, the then Minister for Enterprise, Trade and Employment, Micheál Martin T.D., announced the establishment of an advisory group (the Group) to review the current legislative framework regarding the public interest aspects of media mergers in Ireland. This review was undertaken in the context of a wider review taking place on the operation and implementation of the Competition Act 2002. 1.2 The Group was asked to examine the provisions of the Competition Act 2002 in relation to media mergers and in particular the “relevant criteria” specified in the Act, by reference to which the Minister currently considers media mergers. 1.3 The Terms of Reference of the Group were:- To review and to consider the current levels of plurality and diversity in the media sector in Ireland. To examine and review the “relevant criteria” as currently defined in the Act. To examine and consider how the application of the “relevant criteria” should be given effect and by whom. To examine the role of the Minister in assessing the “relevant criteria” from a public interest perspective and the best mechanism to do so. To examine international best practice, including the applicability of models from other countries. To make recommendations, as appropriate, on the above. 2 1.4 The membership of the Group comprised:- Paul Sreenan S.C. (Chairman) Dr. Olive Braiden. Peter Cassells Marc Coleman John Herlihy Prof. -

Independent Radio (Alphabetical Order) Frequency Finder

Independent Radio (Alphabetical order) Frequency Finder Commercial and community radio stations are listed together in alphabetical order. National, local and multi-city stations A ABSOLUTE RADIO CLASSIC ROCK are listed together as there is no longer a clear distinction Format: Classic Rock Hits Broadcaster: Bauer between them. ABBEY 104 London area, Surrey, W Kent, Herts, Luton (Mx 3) DABm 11B For maps and transmitter details see: Mixed Format Community Swansea, Neath Port Talbot and Carmarthenshire DABm 12A • Digital Multiplexes Sherborne, Dorset FM 104.7 Shropshire, Wolverhampton, Black Country b DABm 11B • FM Transmitters by Region Birmingham area, West Midlands, SE Staffs a DABm 11C • AM Transmitters by Region ABC Coventry and Warwickshire DABm 12D FM and AM transmitter details are also included in the Mixed Format Community Stoke-on-Trent, West Staffordshire, South Cheshire DABm 12D frequency-order lists. Portadown, County Down FM 100.2 South Yorkshire, North Notts, Chesterfield DABm 11C Leeds and Wakefield Districts DABm 12D Most stations broadcast 24 hours. Bradford, Calderdale and Kirklees Districts DABm 11B Stations will often put separate adverts, and sometimes news ABSOLUTE RADIO East Yorkshire and North Lincolnshire DABm 10D and information, on different DAB multiplexes or FM/AM Format: Rock Music Tees Valley and County Durham DABm 11B transmitters carrying the same programmes. These are not Broadcaster: Bauer Tyne and Wear, North Durham, Northumberland DABm 11C listed separately. England, Wales and Northern Ireland (D1 Mux) DABm 11D Greater Manchester and North East Cheshire DABm 12C Local stations owned by the same broadcaster often share Scotland (D1 Mux) DABm 12A Central and East Lancashire DABm 12A overnight, evening and weekend, programming. -

Distribution Rules

PERFORMING RIGHT SOCIETY LIMITED DISTRIBUTION RULES Appendices APPENDIX Standard distribution cycle Distribution Source April July October December Reconciliation BBC radio Oct – Dec Jan - Mar Apr - Jun Jul - Sept July BBC TV Sept - Dec Jan - Mar Apr - Jun Jul - Aug July BSkyB TV Sept - Dec Jan - Mar Apr - Jun Jul - Aug October All other TV Re Sept - Dec Jan - Mar Apr - Jun Jul - Aug April po (exc. music TV channels) rti All other radio ng Oct – Dec Jan - Mar Apr - Jun Jul - Sept April (and music TV channels) Pe ri od Public performance * Oct – Dec Jan - Mar Apr - Jun Jul - Sept April Online ** Oct – Dec Jan - Mar Apr - Jun Jul - Sept N/A International Jul-Dec Jan-Jun N/A (agencies) International Varies depending on affiliate society timetable N/A (affiliate societies) *Concerts using the live concert service are distributed outside the four major distributions with a target of within 60 days of the concert **It is not always possible to adhere to this timetable for some online services Broadcast sampling rates Since 2010 new TV and radio services are sampled at the following minimum rates. TV Sampling Threshold Sample Band Days 4 0-15K 10 15-30K 37 30-60K 91 60-100K 181 100-200K 365 200K+ Radio Sampling Threshold Sample Band Days 4 £0-£50K 8 £50-£100K 16 £100-£200K 32 £200-£500K 365 £750K+ At present services that existed before 2010 are still sampled at minimum rates calculated using a complex statistical formula. In practice, because of electronic reporting and the use of music recognition technology, many services have much higher sample rates, bordering on census for non-advertising plays. -

Wireless Group Local FM Stations

Section 355 Review of Output Wireless group local FM stations [] Redacted for publication Publication Date: 14 November 2019 Section 355 Review: Wireless group local FM stations Introduction When a local commercial radio licence undergoes a change of control (this includes licence transfer), Ofcom is required, under section 355 of the Communications Act 2003 (‘the Act’), to undertake a review of the effects or likely effects of the change of control in relation to: • the quality and range of programmes included in the service; • the character of the service, and; • the extent to which Ofcom’s duty under section 314 of the Act is performed in relation to the service. Ofcom’s duty under section 314 of the Act relates to securing the inclusion of an appropriate amount of local material, and a suitable proportion of locally-made programmes in the service. Under section 356 of the Act, where it appears to Ofcom from its review that the change of control would be prejudicial to any of the three matters listed above, then it must vary the licence, by including such conditions as it considers appropriate, with a view to ensuring that the relevant change of control is not so prejudicial. In doing so, any new or varied conditions must be such that the licence holder would have satisfied them throughout the three months immediately before the change of control. Ofcom is required to publish a report of its review, setting out its conclusions and any steps it proposes to take under section 356. Where Ofcom proposes to vary the licence, it is required to give the licence holder a reasonable opportunity to make representations about the variation.