Tadpoles Find the Sun

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of Turnus in the Aeneid Michael Kelley

Tricks and Treaties: The “Trojanification” of Turnus in the Aeneid Michael Kelley, ‘18 In a poem characterized in large part by human intercourse with the divine, one of the most enigmatic augury passages of Virgil’s Aeneid occurs in Book XII, in which Juturna delivers an omen to incite the Latins toward breaking their treaty with the Trojans. The augury passage is, at a superficial level, a deceptive exhortation addressed to the Latins, but on a meta- textual, intra-textual, and inter-textual level, a foreshadowing of the downfall of Turnus and the Latins. In this paper, I will begin by illustrating how the deception within Juturna’s rhetoric and linguistic allusions to deception in the eagle apparition indicate a true meaning which supersedes Juturna’s intended trickery. Then, in demonstrating inter-textual and intra-textual paradigms for Turnus, I will explain how the omen, and the associations called for therein, actually anticipate Turnus’s impending, sacrificial death. Finally, I will address the implications of my claim, presenting an interpretation of a sympathetic Turnus and a pathetically deceived Juturna. While the omen which follows is not necessarily false, Juturna’s rhetoric, spoken in the guise of Turnus’s charioteer Metiscus,1 is marked by several rhetorical techniques that are, ultimately, fruitful in inciting the Latins toward combat. Attempting to invoke their better reason, Juturna begins the speech with several rhetorical questions that appeal to their sense of honor and their devotion to Turnus.2 Her description of the Trojans as a fatalis manus, translated by Tarrant as “a troop protected by fate,”3 is most likely sarcastic, referencing what she deems a self-important insistence on prophecy from the Trojans. -

Baudelaire's Swan Song

Baudelaire's Swan Song A lecture by Jonathan Tuck Delivered at St. John's College, Annapolis-October 13, 2006 This lecture is dedicated to the memory of Brother Robert Smith. The late Reverend J. Winfree Smith, a long-time Annapolis tutor, a historian of the New Program, an Anglican priest, a scholar and a Virginia gentleman of the old school, used to assert that Charles Baudelaire was a greater poet than Homer. Winfree's view counts for quite a lot with me, but I would not go that far. I am willing to say that Baudelaire is the greatest poet of the last two hundred years or so, the first and most essential of"modern" writers and the one who best articulates our own feelings of what it is to be modern. And I think that Le Cygne is Baudelaire's greatest poem, although perhaps not his most typical one. This valuation sets the bar quite high enough for me, for this evening at least. Thus, for about the last twenty years, I have held the writing of this lecture before me as a daunting but imperative task. I have a further reason for trepidation: I believe that it's indispensable, before discussing any poem, first to read it aloud. But I am keenly aware that, unlike some of you, I am very far from a native or even a fluent speaker of French,. My hope is that in enunciating the poem aloud, I can bring out some of its metrical features through a kind of exaggeration; that may compensate you for having to hear my accented reading. -

The Aeneid Virgil

The Aeneid Virgil TRANSLATED BY A. S. KLINE ROMAN ROADS MEDIA Classical education, from a Christian perspective, created for the homeschool. Roman Roads combines its technical expertise with the experience of established authorities in the field of classical education to create quality video courses and resources tailored to the homeschooler. Just as the first century roads of the Roman Empire were the physical means by which the early church spread the gospel far and wide, so Roman Roads Media uses today’s technology to bring timeless truth, goodness, and beauty into your home. By combining excellent instruction augmented with visual aids and examples, we help inspire in your children a lifelong love of learning. The Aeneid by Virgil translated by A. S. Kline This text was designed to accompany Roman Roads Media's 4-year video course Old Western Culture: A Christian Approach to the Great Books. For more information visit: www.romanroadsmedia.com. Other video courses by Roman Roads Media include: Grammar of Poetry featuring Matt Whitling Introductory Logic taught by Jim Nance Intermediate Logic taught by Jim Nance French Cuisine taught by Francis Foucachon Copyright © 2015 by Roman Roads Media, LLC Roman Roads Media 739 S Hayes St, Moscow, Idaho 83843 A ROMAN ROADS ETEXT The Aeneid Virgil TRANSLATED BY H. R. FAIRCLOUGH BOOK I Bk I:1-11 Invocation to the Muse I sing of arms and the man, he who, exiled by fate, first came from the coast of Troy to Italy, and to Lavinian shores – hurled about endlessly by land and sea, by the will of the gods, by cruel Juno’s remorseless anger, long suffering also in war, until he founded a city and brought his gods to Latium: from that the Latin people came, the lords of Alba Longa, the walls of noble Rome. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Publisher's Note ............................................................................................................................................................ v Absalom Absalom!—William Faulkner ....................................................................................................................... 1 Absalom and Achitophel—John Dryden ...................................................................................................................... 1 Adam Bede—George Eliot ........................................................................................................................................... 2 Adonais—Percy Bysshe Shelley ................................................................................................................................... 2 The Adventures of Augie March—Saul Bellow ............................................................................................................ 3 The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn—Mark Twain .................................................................................................... 3 The Adventures of Tom Sawyer—Mark Twain ............................................................................................................ 4 Aeneid—Vergil .............................................................................................................................................................. 4 The Age of Innocence—Edith Wharton ...................................................................................................................... -

Character As Fate in Ancient Literature | Achilles, Aeneas, Rostam, and Cyrus the Great

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1999 Character as fate in ancient literature | Achilles, Aeneas, Rostam, and Cyrus the Great Natalie Mary Gould The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Gould, Natalie Mary, "Character as fate in ancient literature | Achilles, Aeneas, Rostam, and Cyrus the Great" (1999). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 1775. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/1775 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University ofIVIONTANA Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. ** ** Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature Yes, I grant permission No, I do not grant permission Author's Signature Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. Character As Fate In Ancient Literature; Achilles/ Aeneas, Rostam, And Cyrus The Great by; Natalie Mary Gould presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters Of Interdisciplinary Studies The University Of Montana 1999 Approved by: ChaiiCperson, John G. -

Tales of Troy

TALES OF TROY: ULYSSES THE SACKER OF CITIES by Andrew Lang THE BOYHOOD AND PARENTS OF ULYSSES Long ago, in a little island called Ithaca, on the west coast of Greece, there lived a king named Laertes. His kingdom was small and mountainous. People used to say that Ithaca “lay like a shield upon the sea,” which sounds as if it were a flat country. But in those times shields were very large, and rose at the middle into two peaks with a hollow between them, so that Ithaca, seen far off in the sea, with her two chief mountain peaks, and a cloven valley between them, looked exactly like a shield. The country was so rough that men kept no horses, for, at that time, people drove, standing up in little light chariots with two horses; they never rode, and there was no cavalry in battle: men fought from chariots. When Ulysses, the son of Laertes, King of Ithaca grew up, he never fought from a chariot, for he had none, but always on foot. If there were no horses in Ithaca, there was plenty of cattle. The father of Ulysses had flocks of sheep, and herds of swine, and wild goats, deer, and hares lived in the hills and in the plains. The sea was full of fish of many sorts, which men caught with nets, and with rod and line and hook. Thus Ithaca was a good island to live in. The summer was long, and there was hardly any winter; only a few cold weeks, and then the swallows came back, and the plains were like a garden, all covered with wild flowers—violets, lilies, narcissus, and roses. -

«Prometheus» 46, 2020, 153-167! ADSPIRATE CANENTI: the MUSES in VIRGIL's AENEID the Virgilian Employment of the Muses In

«Prometheus» 46, 2020, 153-167! ADSPIRATE CANENTI: THE MUSES IN VIRGIL’S AENEID The Virgilian employment of the Muses in his epic Aeneid has been called “purely conventional”1. The present study will consider closely every appearance of these patronesses of song in the poem, with a view to de- monstrating how Virgil’s attention to the Muses presents a significant aspect of his use of divine machinery in the explication of his larger themes about the import of his epic, in particular its concern with the relationship of Aeneas’ Troy to Turnus’ Italy in the establishment of the future Rome2. The “Muse” is the first divine being mentioned in Virgil’s poem, as the narrator calls on her to recall the causes of the anger of Juno that spelled such trouble and strife for Aeneas: Musa, mihi causas memora, quo numine laeso quidve dolens regina deum tot volvere casus insignem pietate virum, tot adire labores impulerit. Tantaene animis caelestibus irae? (1.8-11)3 This famous passage from the proem of the epic is the subject of the celebrated “Virgil Mosaic” found in Sousse, Tunisia and now housed in the Bardo Museum in Tunis4. Virgil is seated between two Muses, the scroll on his lap inscribed with verse 8 and the first word of verse 9. The muse on the left is reading from her own scroll, while the one on the right is holding a tragic mask. The second muse is thus confidently identified as Melpomene; the other has been labeled either Calliope – the muse of epic – or Clio, the muse of history. -

Virgil, Aeneid 4.1-299

To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/162 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Ingo Gildenhard is currently Professor of Classics and the Classical Tradition at Durham University. In January 2013, he will take up a Lectureship in the Faculty of Classics, Cambridge University, and a Fellowship at King’s College Cambridge. His previous publications include the monographs Paideia Romana: Cicero’s Tusculan Disputations (Cambridge, 2007) and Creative Eloquence: The Construction of Reality in Cicero’s Speeches (Oxford, 2011). He has also published another textbook with Open Book Publishers, Cicero, Against Verres, 2.1.53-86. Virgil, Aeneid 4.1–299: Latin Text, Study Questions, Commentary and Interpretative Essays Ingo Gildenhard Open Book Publishers CIC Ltd., 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com © Ingo Gildenhard This book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 unported license available at: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by- nc/3.0/ This license allows you to share, copy, distribute, transmit and adapt the work, but not for commerical purposes. The work must be attributed to the respective authors (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). As with all Open Book Publishers titles, digital material and resources associated with this volume are available from our website at: http://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/162 ISBN Hardback: 978-1-909254-16-9 ISBN Paperback: 978-1-909254-15-2 ISBN Digital (PDF): 978-1-909254-17-6 ISBN Digital ebook (epub): 978-1-909254-18-3 ISBN Digital ebook (mobi): 978-1-909254-19-0 Cover image: Augustin Cayot, La mort de Didon (1711). -

Creation and the Gods Charades

UNIT 1: CREATION AND THE GODS CHARADES 100 HANDED MONSTERS ECHO POSEIDON APHRODITE HADES PROMETHEUS APOLLO HARPY PSYCHE ARES HEBE PYRAMUS AND THISBE ARGUS HELIOS RIVER STYX ARTEMIS HEPHAESTUS SATYR ATHENA HERA SCYLLA ATLAS HERMES SISYPHUS CENTAUR HESTIA THE FATES CERBERUS IRIS THE NINE MUSES CHAOS MIDAS THE OLYMPICS CHARON THE BOATMAN MOTHER EARTH THE TITANS CHARYBDIS MOUNT OLYMPUS THE TWELVE OLYMPIANS CHIRON NARCISSUS THE UNDERWORLD CYCLOPS NYMPHS THUNDERBOLT DEMETER PAN TRIDENT DEUCALION PANDORA URANUS DIONYSUS PERSEPHONE ZEUS UNIT 2: HEROES CHARADES ANDROMEDA ICARUS RIDDLE ANTI-HERO ISLAND OF CRETE SEA SERPENT ARIADNE JASON SHE-BEAR ATALANTA JOSEPH CAMPBELL SPHINX BELLEROPHON KING MINOS THE 12 LABORS CAP OF INVISIBILITY LABYRINTH THE AMAZONS CHIMAERA LYRE THE ARGO CLEANING THE STABLES MAN-EATING HORSES THE ARGONAUTS CROWN OF LIGHT MEDEA THE WITCH THE GOLDEN FLEECE DAEDALUS MEDUSA THE GRAY WOMEN FEMALE WARRIOR MELEAGER THE HERO’S JOURNEY FLYING RAM MINOTAUR THE HYDRA FOOTRACE NEMEAN LION THE MILKY WAY GIANT BOAR OEDIPUS THESEUS GOLDEN APPLES ORACLE OF DELPHI TIRESIAS GOLDEN THREAD PEGASUS WINGED SANDALS HERACLES PERSEUS JOCASTA HIPPOMENES PHAETHON MAGIC BRIDLE UNIT 3: THE TROJAN WAR CHARADES A THOUSAND SHIPS ERIS PARIS ACHILLES FALL OF TROY PATROCLUS AENEAS FORGING ARMOR PRIAM AGAMEMNON FUNERAL OF HECTOR PRINCE HECTOR AJAX HELEN OF SPARTA PRINCE PHILOCTETES ANDROMACHE HELEN OF TROY PYRRHUS ARROW IN THE HEEL HOMER THE POET QUEEN HECUBA ASTYANAX ILIUM SHIELD OF ACHILLES BLIND POET IPHIGENIA SINON BODY OF HECTOR JUDGMENT OF PARIS TEN YEARS -

Love and the Symbolic Journey in Seferis' Mythistorema by C

Jo LLENIC IASPO A Quarterly Review VOL. VIII, No. 3 FALL 1981 Publisher: LEANDROS PAPATHANASIOU Editorial Board: DAN GEORGAKAS PASCHALIS M. KITROMILIDES PETER PAPPAS YIANNIS P. ROUBATIS Founding Editor: NIKOS PETROPOULOS The Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora air mail; Institutional—$20.00 for one is a quarterly review published by Pella year, $35.00 for two years. Single issues Publishing Company, Inc., 461 Eighth cost $3.50; back issues cost $4.50. Avenue, New York, NY 10001, U.S.A., in March, June, September, and Decem- Advertising rates can be had on request ber. Copyright © 1981 by Pella Publish- by writing to the Managing Editor. ing Company. Articles appearing in this Journal are The editors welcome the freelance sub- abstracted and/or indexed in Historical mission of articles, essays and book re- Abstracts and America: History and views. All submitted material should be Life; or in Sociological Abstracts; or in typewritten and double-spaced. Trans- Psychological Abstracts; or in the Mod- lations should be accompanied by the ern Language Association Abstracts (in- original text. Book reviews should be cludes International Bibliography) or in approximately 600 to 1,200 words in International Political Science Abstracts length. Manuscripts will not be re- in accordance with the relevance of con- turned unless they are accompanied by tent to the abstracting agency. a stamped, self-addressed envelope. All articles and reviews published in Subscription rates: Individual—$12.00 the Journal represent only the opinions for one year, $22.00 for two years; of the individual authors; they do not Foreign—$15.00 for one year by surface necessarily reflect the views of the mail; Foreign—$20.00 for one year by editors or the publisher NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS C. -

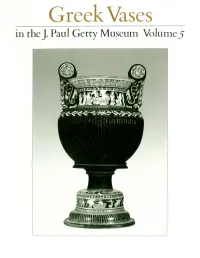

Greek Vases in the J. Paul Getty Museum, Volume 5, OPA 7

Occasional Papers on Antiquities, 7 Greeksase s in the J. Paul Getty Museum Volume 5 MALIBU, CALIFORNIA 1991 V © 1991 The J. Paul Getty Museum 17985 Pacific Coast Highway Malibu, California 90265-5799 (213) 459-7611 Mailing address: P.O. Box 2112 Santa Monica, California 90406 Christopher Hudson, Head of Publications Cynthia Newman Helms, Managing Editor Karen Schmidt, Production Manager Leslee Holderness, Sales and Distribution Manager Project staff: Editor: Marion True, Curator of Antiquities Manuscript Editor: Benedicte Gilman Assistant Editor: Mary Holtman Designer: Patricia Inglis Production Coordinator: Elizabeth Burke Kahn Production Artist: Thea Piegdon All photographs by the Department of Photographic Services, J. Paul Getty Museum, unless otherwise noted. Typography by TypeLink, San Diego Printed by Alan Lithograph Inc., Los Angeles Cover: A dinoid volute-krater by the Meleager Painter. Malibu, J. Paul Getty Museum 87.AE.93. Side A. See article page 107. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data (Revised for vol. 5) Greek vases in the J. Paul Getty Museum. (Occasional papers on antiquities; 1,) English and German. Includes bibliographical references. 1. Vases, Greek —Addresses, essays, lectures. 2. Vase-paintings, Greek —Themes, motives. 3. Vases, Etruscan. 4. Vase-painting, Etruscan —Themes, motives. 5. Vases —California —Malibu. 6. J. Paul Getty Museum. I. J. Paul Getty Museum. II. Series. NK4623.M37J24 1983 738.3'82'093807479493 82-49024 ISBN 0-89236-058-5 (pbk. : v. 1) ISBN 0-89236-184-0 3» Contents Bellerophon and the Chimaira on a Lakonian Cup by the Boreads Painter Conrad M. Stibbe Six's Technique at the Getty Janet Burnett Grossman A New Representation of a City on an Attic Red-figured Kylix William A. -

The Reception of Epic Kleos in Greek Tragedy Dissertation Presented In

The Reception of Epic kleos in Greek Tragedy Dissertation Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of doctor of philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University Agapi Stefanidou, MA Graduate Program in Greek and Latin The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Tom Hawkins, Advisor Benjamin Acosta-Hughes Fritz Graf Copyright by Agapi Stefanidou 2014 Abstract In this dissertation I examine how Greek tragedy received the epic concept of kleos. Although kleos in epic and epinician poetry has a specific social and ideological function, its usage in Attic drama exhibits its incompatibility with the pragmatic environment of a polis and reflects the difficulties such a value provokes when measured in circumstances similar to those of fifth century Athens, namely within a democracy where no one is allowed to enjoy a rarefied status and where familial and city law is part of the audience’s quotidian court experience. Although the word kleos is encountered in the plays of all three great tragedians, I argue that we can observe a different approach between the usages of Aeschylus and Sophocles on the one hand and Euripides on the other. The concept of kleos occurs many more times in Euripides’ tragic corpus and in the majority it is claimed by female characters. However, since in epic and epinician poetry kleos is normally connected with men, namely bravery, warrior prowess, physical abilities and admirable achievements either on the battlefield or at athletic Games, I chose to base my argument on male tragic characters. My first study case is Orestes, who is presented in the Odyssey as an exemplum of kleos and who is is connected with a kleos discourse in the relevant plays of all three tragedians.