Download Vol. 13, No. 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Occurrences of Small Mammal Species in a Mixedgrass Prairie in Northwestern North Dakota

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln The Prairie Naturalist Great Plains Natural Science Society 6-2007 Occurrences of Small Mammal Species in a Mixedgrass Prairie in Northwestern North Dakota, Robert K. Murphy Richard A. Sweitzer John D. Albertson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tpn Part of the Biodiversity Commons, Botany Commons, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, Natural Resources and Conservation Commons, Systems Biology Commons, and the Weed Science Commons This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Natural Science Society at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Prairie Naturalist by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. NOTES OCCURRENCES OF SMALL MAMMAL SPECIES IN A MIXED-GRASS PRAIRIE IN NORTHWESTERN NORTH DAKOTA -- Documentation is limited for many species of vertebrates in the northern Great Plains, particularly northwestern North Dakota (Bailey 1926, Hall 1981). Here we report relative abundances of small « 450 g) species of mammals that were captured incidental to surveys of amphibians and reptiles at Lostwood National Wildlife Refuge (LNWR) in northwestern North Dakota from 1985 to 1987 and 1999 to 2000. Our records include a modest range extension for one species. We also comment on relationships of small mammals on the refuge to vegetation changes associated with fire and grazing disturbances. LNWR encompassed 109 km2 of rolling to hilly moraine in Burke and Mountrail counties, North Dakota (48°37'N; 102°27'W). The area was mostly a native needlegrass-wheatgrass prairie (Stipa-Agropyron; Coupland 1950) inter spersed with numerous wetlands 'x = 40 basins/km2) and patches of quaking aspen trees (Populus tremuloides; x = 0.4 ha/patch and 4.8 patches/km2; 1985 data in Murphy 1993:23), with a semi-arid climate. -

Proceedings of the Third Annual Northeastern Forest Insect Work Conference

Proceedings of the Third Annual Northeastern Forest Insect Work Conference New Haven, Connecticut 17 -19 February 1970 U.S. D.A. FOREST SERVICE RESEARCH PAPER NE-194 1971 NORTHEASTERN FOREST EXPERIMENT STATION, UPPER DARBY, PA. FOREST SERVICE, U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE WARREN T. DOOLITTLE, DIRECTOR Proceedings of the Third Annual Northeastern Forest Insect Work Conference CONTENTS INTRODUCTION-Robert W. Campbell ........................... 1 TOWARD INTEGRATED CONTROL- D. L,Collifis ...............................................................................2 POPULATION QUALITY- 7 David E. Leonard ................................................................... VERTEBRATE PREDATORS- C. H. Backner ............................................................................2 1 INVERTEBRATE PREDATORS- R. I. Sailer ..................................................................................32 PATHOGENS-Gordon R. Stairs ...........................................45 PARASITES- W.J. Tamock and I. A. Muldrew .......................................................................... 59 INSECTICIDES-Carroll Williams and Patrick Shea .............................................................................. 88 INTEGRATED CONTROL, PEST MANAGEMENT, OR PROTECTIVE POPULATION MANAGEMENT- R. W. Stark ..............................................................................1 10 INTRODUCTION by ROBERT W. CAMPBELL, USDA Forest Service, Northeastern Forest Experiment Station, Hamden, Connecticut. ANYPROGRAM of integrated control is -

Northern Short−Tailed Shrew (Blarina Brevicauda)

FIELD GUIDE TO NORTH AMERICAN MAMMALS Northern Short−tailed Shrew (Blarina brevicauda) ORDER: Insectivora FAMILY: Soricidae Blarina sp. − summer coat Credit: painting by Nancy Halliday from Kays and Wilson's Northern Short−tailed Shrews have poisonous saliva. This enables Mammals of North America, © Princeton University Press them to kill mice and larger prey and paralyze invertebrates such as (2002) snails and store them alive for later eating. The shrews have very limited vision, and rely on a kind of echolocation, a series of ultrasonic "clicks," to make their way around the tunnels and burrows they dig. They nest underground, lining their nests with vegetation and sometimes with fur. They do not hibernate. Their day is organized around highly active periods lasting about 4.5 minutes, followed by rest periods that last, on average, 24 minutes. Population densities can fluctuate greatly from year to year and even crash, requiring several years to recover. Winter mortality can be as high as 90 percent in some areas. Fossils of this species are known from the Pliocene, and fossils representing other, extinct species of the genus Blarina are even older. Also known as: Short−tailed Shrew, Mole Shrew Sexual Dimorphism: Males may be slightly larger than females. Length: Range: 118−139 mm Weight: Range: 18−30 g http://www.mnh.si.edu/mna 1 FIELD GUIDE TO NORTH AMERICAN MAMMALS Least Shrew (Cryptotis parva) ORDER: Insectivora FAMILY: Soricidae Least Shrews have a repertoire of tiny calls, audible to human ears up to a distance of only 20 inches or so. Nests are of leaves or grasses in some hidden place, such as on the ground under a cabbage palm leaf or in brush. -

Appendix D: Species Lists

Appendix D: Species Lists Appendix D: Species Lists Mammal Species List for Rice Lake NWR ........................................................................................................ 81 Butterfly and Moth Species List, Rice Lake NWR ............................................................................................ 83 Dragonfly and Damselfly Species List, Rice Lake NWR ................................................................................... 86 Amphibian and Reptile Species List, Rice Lake NWR ...................................................................................... 90 Fish Species List, Rice Lake NWR and the Sandstone Unit of Rice Lake NWR ............................................... 91 Mollusk and Crustacean Species List, Rice Lake NWR and the Sandstone Unit of Rice Lake NWR .............. 92 Bird Species List, Rice Lake NWR ..................................................................................................................... 93 Sandstone Unit of Rice Lake NWR Bird Species List ..................................................................................... 103 Rice Lake NWR Tree and Shrub Species List ................................................................................................. 112 Vegetation Species List, Rice Lake NWR ....................................................................................................... 116 Rice Lake NWR and Mille Lacs NWR Comprehensive Conservation Plan 79 Appendix D: Species Lists Mammal Species List for Rice -

Checklist of Amphibians, Reptiles, Birds and Mammals of New York

CHECKLIST OF AMPHIBIANS, REPTILES, BIRDS AND MAMMALS OF NEW YORK STATE Including Their Legal Status Eastern Milk Snake Moose Blue-spotted Salamander Common Loon New York State Artwork by Jean Gawalt Department of Environmental Conservation Division of Fish and Wildlife Page 1 of 30 February 2019 New York State Department of Environmental Conservation Division of Fish and Wildlife Wildlife Diversity Group 625 Broadway Albany, New York 12233-4754 This web version is based upon an original hard copy version of Checklist of the Amphibians, Reptiles, Birds and Mammals of New York, Including Their Protective Status which was first published in 1985 and revised and reprinted in 1987. This version has had substantial revision in content and form. First printing - 1985 Second printing (rev.) - 1987 Third revision - 2001 Fourth revision - 2003 Fifth revision - 2005 Sixth revision - December 2005 Seventh revision - November 2006 Eighth revision - September 2007 Ninth revision - April 2010 Tenth revision – February 2019 Page 2 of 30 Introduction The following list of amphibians (34 species), reptiles (38), birds (474) and mammals (93) indicates those vertebrate species believed to be part of the fauna of New York and the present legal status of these species in New York State. Common and scientific nomenclature is as according to: Crother (2008) for amphibians and reptiles; the American Ornithologists' Union (1983 and 2009) for birds; and Wilson and Reeder (2005) for mammals. Expected occurrence in New York State is based on: Conant and Collins (1991) for amphibians and reptiles; Levine (1998) and the New York State Ornithological Association (2009) for birds; and New York State Museum records for terrestrial mammals. -

List of 28 Orders, 129 Families, 598 Genera and 1121 Species in Mammal Images Library 31 December 2013

What the American Society of Mammalogists has in the images library LIST OF 28 ORDERS, 129 FAMILIES, 598 GENERA AND 1121 SPECIES IN MAMMAL IMAGES LIBRARY 31 DECEMBER 2013 AFROSORICIDA (5 genera, 5 species) – golden moles and tenrecs CHRYSOCHLORIDAE - golden moles Chrysospalax villosus - Rough-haired Golden Mole TENRECIDAE - tenrecs 1. Echinops telfairi - Lesser Hedgehog Tenrec 2. Hemicentetes semispinosus – Lowland Streaked Tenrec 3. Microgale dobsoni - Dobson’s Shrew Tenrec 4. Tenrec ecaudatus – Tailless Tenrec ARTIODACTYLA (83 genera, 142 species) – paraxonic (mostly even-toed) ungulates ANTILOCAPRIDAE - pronghorns Antilocapra americana - Pronghorn BOVIDAE (46 genera) - cattle, sheep, goats, and antelopes 1. Addax nasomaculatus - Addax 2. Aepyceros melampus - Impala 3. Alcelaphus buselaphus - Hartebeest 4. Alcelaphus caama – Red Hartebeest 5. Ammotragus lervia - Barbary Sheep 6. Antidorcas marsupialis - Springbok 7. Antilope cervicapra – Blackbuck 8. Beatragus hunter – Hunter’s Hartebeest 9. Bison bison - American Bison 10. Bison bonasus - European Bison 11. Bos frontalis - Gaur 12. Bos javanicus - Banteng 13. Bos taurus -Auroch 14. Boselaphus tragocamelus - Nilgai 15. Bubalus bubalis - Water Buffalo 16. Bubalus depressicornis - Anoa 17. Bubalus quarlesi - Mountain Anoa 18. Budorcas taxicolor - Takin 19. Capra caucasica - Tur 20. Capra falconeri - Markhor 21. Capra hircus - Goat 22. Capra nubiana – Nubian Ibex 23. Capra pyrenaica – Spanish Ibex 24. Capricornis crispus – Japanese Serow 25. Cephalophus jentinki - Jentink's Duiker 26. Cephalophus natalensis – Red Duiker 1 What the American Society of Mammalogists has in the images library 27. Cephalophus niger – Black Duiker 28. Cephalophus rufilatus – Red-flanked Duiker 29. Cephalophus silvicultor - Yellow-backed Duiker 30. Cephalophus zebra - Zebra Duiker 31. Connochaetes gnou - Black Wildebeest 32. Connochaetes taurinus - Blue Wildebeest 33. Damaliscus korrigum – Topi 34. -

Cinereus Shrew

Alaska Species Ranking System - Cinereus shrew Cinereus shrew Class: Mammalia Order: Eulipotyphla Sorex cinereus Review Status: Peer-reviewed Version Date: 20 November 2018 Conservation Status NatureServe: Agency: G Rank:G5 ADF&G: IUCN:Least Concern Audubon AK: S Rank: S5 USFWS: BLM: Final Rank Conservation category: V. Orange unknown status and either high biological vulnerability or high action need Category Range Score Status -20 to 20 0 Biological -50 to 50 -42 Action -40 to 40 32 Higher numerical scores denote greater concern Status - variables measure the trend in a taxon’s population status or distribution. Higher status scores denote taxa with known declining trends. Status scores range from -20 (increasing) to 20 (decreasing). Score Population Trend in Alaska (-10 to 10) 0 Unknown. Distribution Trend in Alaska (-10 to 10) 0 Appears to have expanded its distribution northward into tundra habitats (Hope et al. 2013a), but its distribution at the southern end of its range is unknown. While this northward shift is expected to continue, models disagree whether its overall distribution in Alaska will expand (Hope et al. 2013a; 2015) or contract (Baltensperger and Huettmann 2015a; Marcot et al. 2015). Status Total: 0 Biological - variables measure aspects of a taxon’s distribution, abundance and life history. Higher biological scores suggest greater vulnerability to extirpation. Biological scores range from -50 (least vulnerable) to 50 (most vulnerable). Score Population Size in Alaska (-10 to 10) -10 Common and abundant throughout the state (Cook and MacDonald 2006; Baltensperger and Huettmann 2015b). Extensive field surveys across Alaska consistently recorded S. cinereus as the dominant small mammal species (Cook and MacDonald 2006; Baltensperger and Huettmann 2015b), and more than 13,500 specimens have been collected in Alaska in the past 120 years (ARCTOS 2016). -

SEC 1987 Non-Game Animals in the Skagit Valley of Dritish Columbia

E~JIO Non-game animals in the Skagit Valley of Dritish Columbia : literature r eview and research directions La urie L . Kremsat er SEC 1987 /fl Non-game animals in the Skagit Valley of British Columbia: literature review and research directions Laurie L. Kremsater prepared for Ministry of Environment and Parks January 1987 -1- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS r I am indebted to Fred Bunnell for reviewing this manuscript. ^ Thanks to Dave Dunbar for supplying valuable information and necessary literature. r To the Vertebrate Zoology Division of the British Columbia f Provincial Museum, particularly Mike McNall and Dave Nagorsen, I am grateful for the access provided me to the wildlife record f" scheme and the reprint collections. Thanks also to Richard C Cannings of the Vertebrate Museum of the Department of Zoology of the University of British Columbia for access to wildlife sighting records. H Thanks to Anthea Farr and Barry Booth for their first hand observations of non-game wildlife in the Skagit. Thanks also to Fred Bunnell, Andrew Harcombe, Alton Harestad, Brian Nyberg, and f' Steve Wetmore for their input into potential research directions for non-game animals in the Skagit Valley. ( f I ABSTRACT Extant data on the abundance, distribution, and diversity o non-game animals of the Skagit Valley (specifically, small mammals, non-game avifauna, cavity-using species, and waterfowl) are reviewed. Principal sources include Slaney (1973), wildlife records of the British Columbia Provincial Museum Vertebrate Division, University of British Columbia Vertebrate Museum records, and naturalist field trip records. Totals of 24 small mammal and 186 avian species have been recorded in the Skagit Valley to date. -

Journal of Natural Science Collections

http://www.natsca.org Journal of Natural Science Collections Title: An overview of the Mammal Collection of Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Author(s): Cervantes, F.A., Vargas‐Cuenca, J. & Hortelano‐Moncada, Y. Source: Cervantes, F.A., Vargas‐Cuenca, J. & Hortelano‐Moncada, Y. (2016). An overview of the Mammal Collection of Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Journal of Natural Science Collections, Volume 4, 4 ‐ 11. URL: http://www.natsca.org/article/2331 NatSCA supports open access publication as part of its mission is to promote and support natural science collections. NatSCA uses the Creative Commons Attribution License (CCAL) http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5/ for all works we publish. Under CCAL authors retain ownership of the copyright for their article, but authors allow anyone to download, reuse, reprint, modify, distribute, and/or copy articles in NatSCA publications, so long as the original authors and source are cited. Cervantes et al., 2016. JoNSC 4, pp.4-11 An overview of the Mammal Collection of Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Fernando A. Cervantes*, Julieta Vargas-Cuenca, and Yolanda Hortelano-Moncada Received: 31/08/2016 Accepted: 10/11/2016 Colección Nacional de Mamíferos, Departamento de Zoología,Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, AP 70-153, Ciudad Universitaria, CP 04510 CDMX, México *Corresponding author: [email protected] Citation: Cervantes, F.A., Vargas-Cuenca, J., and Hortelano-Moncada, Y., 2016. An overview of the Mammal Collection of Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Journal of Natural Science Collections, 4, pp.4-11. -

Final Plan Chippewa Plains-Pine Moraines and Outwash Plains-SFRMP

APPENDIX L Terrestrial, Vertebrate Species List Chippewa Plains / Pine Moraines and Outwash Plains ECS Subsections a Species Common Name: Are standardized nomenclature for GAP protocol uses through NatureServe and its related searchable plant, animal and ecological communities database called NatureServe Explorer (2002) located at: http://www.natureserveexplorer.org. b Resident Status: R=Regular resident as Breeding, Nesting, or Migratory (acceptable record exists in at least eight of the past 10 years); PR=Permanent Resident (exists year- round). c State Legal Status: E=State Endangered; T=State Threatened; SC=State Species of Special Concern; BG=Big Game; SG=Small Game; F=Furbearer; MW=Migratory Waterfowl; UB=Unprotected Bird; PB=Protected Bird; PWA=Protected Wild Animal; UWA=Unprotected Wild Animal. d Federal Legal Status: T=Federal Threatened; E=Federal Endangered; P=Federal Protection by Migratory Bird Treaty Act and/or Bald Eagle Protection Act and/or CITES. e ECS Subsection Resident Status: B=Minnesota breeding record exists for the species; P=Presence known or predicted, as year around resident; M=Spring or fall migrant, non- breeder; SV= Summer visitor, non-breeder; WV=Winter visitor, non-breeder; A=Absent; (L)=Limited distribution within ECS Subsection. * Species of Greatest Conservation Need Terrestrial Vertebrate Species List Minnesota DNR-Division of Fish and Wildlife - Wildlife Resources Assessment ProjectA ECS Subsectione Pine State Federal Moraines/ Resident Legal Legal Outwash Chippewa Common Namea Scientific Name Statusb -

Ecology of Neglected Rodent-Borne American Orthohantaviruses

pathogens Review Ecology of Neglected Rodent-Borne American Orthohantaviruses Nathaniel Mull 1,*, Reilly Jackson 1, Tarja Sironen 2,3 and Kristian M. Forbes 1 1 Department of Biological Sciences, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR 72701, USA; [email protected] (R.J.); [email protected] (K.M.F.) 2 Department of Virology, University of Helsinki, 00290 Helsinki, Finland; Tarja.Sironen@helsinki.fi 3 Department of Veterinary Biosciences, University of Helsinki, 00790 Helsinki, Finland * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 9 April 2020; Accepted: 24 April 2020; Published: 26 April 2020 Abstract: The number of documented American orthohantaviruses has increased significantly over recent decades, but most fundamental research has remained focused on just two of them: Andes virus (ANDV) and Sin Nombre virus (SNV). The majority of American orthohantaviruses are known to cause disease in humans, and most of these pathogenic strains were not described prior to human cases, indicating the importance of understanding all members of the virus clade. In this review, we summarize information on the ecology of under-studied rodent-borne American orthohantaviruses to form general conclusions and highlight important gaps in knowledge. Information regarding the presence and genetic diversity of many orthohantaviruses throughout the distributional range of their hosts is minimal and would significantly benefit from virus isolations to indicate a reservoir role. Additionally, few studies have investigated the mechanisms underlying transmission routes and factors affecting the environmental persistence of orthohantaviruses, limiting our understanding of factors driving prevalence fluctuations. As landscapes continue to change, host ranges and human exposure to orthohantaviruses likely will as well. Research on the ecology of neglected orthohantaviruses is necessary for understanding both current and future threats to human health. -

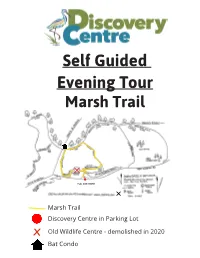

Self Guided Marsh Trail Loop Tour

Self Guided Evening Tour Marsh Trail YOU ARE HERE Marsh Trail Discovery Centre in Parking Lot x Old Wildlife Centre - demolished in 2020 Bat Condo WELCOME TO THE MARSH TRAIL As you embark on the Marsh Trail you will have a good view of the wetlands of the Creston Valley Wildlife Management Area (CVWMA). The CVWMA is a 17 000 acre wetland that is in- ternationally recognized as a Ramsar site and nationally as an Important Bird Area of Canada. The area supports an amazing amount of biodiversity. There are over 300 bird, close to 60 mam- mal, 17 fish, 6 reptile and 6 amphibian species that have been recorded in the area. Plus, there are thousands of invertebrate and plant species! Did you know? • Since 1800, 20 million hectares (~15%) of Canada’s wetlands have been filled in and lost to development. Near major cities and towns, 70% of wetlands have been lost. • When one hectare of wetlands is converted to agricultural land, between 1 and 19 tonnes of carbon dioxide (a greenhouse gas) are emitted to the atmosphere per year. • Most wildlife in the province use wetland habitat at some point in their life cycle. • Wetlands cover about 6% of the land in BC. • One hectare of wetland can store between 9 and 14 million liters of water. NORTH AMERICA’S LARGEST RODENT As you walk along the channel and make your way across the Beaver Boulevard Bridge, stop to admire the dams that our friendly neighborhood beaver has been hard at work creating. These semi-aquatic mammals are often referred to as ‘ecosys- tem engineers’ because of their dams.