Imago 4.Indb 175 08/06/2011 13:01:30 176 Philip Slavin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charters: What Survives?

Banner 4-final.qxp_Layout 1 01/11/2016 09:29 Page 1 Charters: what survives? Charters are our main source for twelh- and thirteenth-century Scotland. Most surviving charters were written for monasteries, which had many properties and privileges and gained considerable expertise in preserving their charters. However, many collections were lost when monasteries declined aer the Reformation (1560) and their lands passed to lay lords. Only 27% of Scottish charters from 1100–1250 survive as original single sheets of parchment; even fewer still have their seal attached. e remaining 73% exist only as later copies. Survival of charter collectionS (relating to 1100–1250) GEOGRAPHICAL SPREAD from inStitutionS founded by 1250 Our picture of documents in this period is geographically distorted. Some regions have no institutions with surviving charter collections, even as copies (like Galloway). Others had few if any monasteries, and so lacked large charter collections in the first place (like Caithness). Others are relatively well represented (like Fife). Survives Lost or unknown number of Surviving charterS CHRONOLOGICAL SPREAD (by earliest possible decade of creation) 400 Despite losses, the surviving documents point to a gradual increase Copies Originals in their use in the twelh century. 300 200 100 0 109 0s 110 0s 111 0s 112 0s 113 0s 114 0s 115 0s 116 0s 1170s 118 0s 119 0s 120 0s 121 0s 122 0s 123 0s 124 0s TYPES OF DONOR typeS of donor – Example of Melrose Abbey’s Charters It was common for monasteries to seek charters from those in Lay Lords Kings positions of authority in the kingdom: lay lords, kings and bishops. -

Francia. Forschungen Zur Westeuropäischen Geschichte

&ƌĂŶĐŝĂ͘&ŽƌƐĐŚƵŶŐĞŶnjƵƌǁĞƐƚĞƵƌŽƉćŝƐĐŚĞŶ'ĞƐĐŚŝĐŚƚĞ ,ĞƌĂƵƐŐĞŐĞďĞŶǀŽŵĞƵƚƐĐŚĞŶ,ŝƐƚŽƌŝƐĐŚĞŶ/ŶƐƚŝƚƵƚWĂƌŝƐ ;/ŶƐƚŝƚƵƚŚŝƐƚŽƌŝƋƵĞĂůůĞŵĂŶĚͿ ĂŶĚϮ1ͬ1;ϭϵϵ4Ϳ K/͗10.11588/fr.1994.1.58796 ZĞĐŚƚƐŚŝŶǁĞŝƐ ŝƚƚĞ ďĞĂĐŚƚĞŶ ^ŝĞ͕ ĚĂƐƐ ĚĂƐ ŝŐŝƚĂůŝƐĂƚ ƵƌŚĞďĞƌƌĞĐŚƚůŝĐŚ ŐĞƐĐŚƺƚnjƚ ŝƐƚ͘ ƌůĂƵďƚ ŝƐƚ ĂďĞƌ ĚĂƐ >ĞƐĞŶ͕ ĚĂƐ ƵƐĚƌƵĐŬĞŶ ĚĞƐ dĞdžƚĞƐ͕ ĚĂƐ ,ĞƌƵŶƚĞƌůĂĚĞŶ͕ ĚĂƐ ^ƉĞŝĐŚĞƌŶ ĚĞƌ ĂƚĞŶ ĂƵĨ ĞŝŶĞŵ ĞŝŐĞŶĞŶ ĂƚĞŶƚƌćŐĞƌ ƐŽǁĞŝƚ ĚŝĞ ǀŽƌŐĞŶĂŶŶƚĞŶ ,ĂŶĚůƵŶŐĞŶ ĂƵƐƐĐŚůŝĞƘůŝĐŚ njƵ ƉƌŝǀĂƚĞŶ ƵŶĚ ŶŝĐŚƚͲ ŬŽŵŵĞƌnjŝĞůůĞŶ ǁĞĐŬĞŶ ĞƌĨŽůŐĞŶ͘ ŝŶĞ ĚĂƌƺďĞƌ ŚŝŶĂƵƐŐĞŚĞŶĚĞ ƵŶĞƌůĂƵďƚĞ sĞƌǁĞŶĚƵŶŐ͕ ZĞƉƌŽĚƵŬƚŝŽŶ ŽĚĞƌ tĞŝƚĞƌŐĂďĞ ĞŝŶnjĞůŶĞƌ /ŶŚĂůƚĞ ŽĚĞƌ ŝůĚĞƌ ŬƂŶŶĞŶ ƐŽǁŽŚů njŝǀŝůͲ ĂůƐ ĂƵĐŚ ƐƚƌĂĨƌĞĐŚƚůŝĐŚ ǀĞƌĨŽůŐƚǁĞƌĚĞŶ͘ Miszellen Horst Fuhrmann LES PREMlfcRES D&CENNIES DES »MONUMENTA GERMANIAE HISTORICA«* Ä l’occasion du 175e anniversaire des MGH, aux amis fran^ais • • »Sanctus amor patriae dat animum«: entouree d’une couronne de feuilles de chene, c’est la devise qui figure en tete de tous les ouvrages edites par les Monumenta Germaniae Historica (dont l’abreviation usuelle est MGH), depuis leur fondation en 1819 jusqu’ä nos jours. Cette maxime iliustre l’esprit qui presida a la fondation des MGH: »l’amour de la patrie« incite ä l’action. Mais il serait pour le moins aventureux d’identifier purement et simplement cet »amour de la patrie«, qualifie, qui plus est, de saint (Sanctus amor), au patriotisme. II exprime plutöt la conviction que l’esprit agissant emane du peuple et de la patrie et que seul le renforcement de cet esprit permet d’esperer des resultats. Que la liberation de »l’esprit populaire« comportät certains dangers pour l’ordre, c’etait ce que craignaient avant tout les forces de restauration, qui venaient tout juste de conquerir ou de reconquerir leurs biens et leurs territoires lors du Congres de Vienne en 1815. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2005/0250845 A1 Vermeersch Et Al

US 2005O250845A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2005/0250845 A1 Vermeersch et al. (43) Pub. Date: Nov. 10, 2005 (54) PSEUDOPOLYMORPHIC FORMS OF A HIV (86) PCT No.: PCT/EP03/50176 PROTEASE INHIBITOR (30) Foreign Application Priority Data (75) Inventors: Hans Wim Pieter Vermeersch, Gent (BE); Daniel Joseph Christiaan May 16, 2002 (EP)........................................ O2O76929.5 Thone, Beerse (BE); Luc Donne O O Marie-Louise Janssens, Malle (BE) Publication Classification Correspondence Address: (51) Int. Cl." ............................................ A61K 31/353 PHILIP S. JOHNSON (52) U.S. Cl. ............................................ 514/456; 549/396 JOHNSON & JOHNSON ONE JOHNSON & JOHNSON PLAZA NEW BRUNSWICK, NJ 08933-7003 (US) (57) ABSTRACT (73) Assignee: Tibotec Parmaceuticeals New pseudopolymorphic forms of (3R,3aS,6aR)-hexahy (21) Appl. No.: 10/514,352 drofuro2,3-blfuran-3-yl (1S,2R)-3-(4-aminophenyl)sul fonyl(isobutyl)amino-1-benzyl-2-hydroxypropylcarbam (22) PCT Fed: May 16, 2003 ate and processes for producing them are disclosed. Patent Application Publication Nov. 10, 2005 Sheet 1 of 18 US 2005/0250845 A1 E. i Patent Application Publication Nov. 10, 2005 Sheet 2 of 18 US 2005/0250845 A1 e Patent Application Publication Nov. 10, 2005 Sheet 3 of 18 US 2005/0250845 A1 Patent Application Publication Nov. 10, 2005 Sheet 4 of 18 US 2005/0250845 A1 92 NO C12S)-No S. C19 Se (Sb so woSC2 AS27 SN22 C23 Figure 4 Patent Application Publication Nov. 10, 2005 Sheet 5 of 18 US 2005/0250845 A1 -- 1800 1600 1400 1200 1000 800 soc wavenumbers (cm) Figure 5 - P1 : - P8'i P19 .. -

Jewish Persecutions and Weather Shocks: 1100-1800⇤

Jewish Persecutions and Weather Shocks: 1100-1800⇤ § Robert Warren Anderson† Noel D. Johnson‡ Mark Koyama University of Michigan, Dearborn George Mason University George Mason University This Version: 30 December, 2013 Abstract What factors caused the persecution of minorities in medieval and early modern Europe? We build amodelthatpredictsthatminoritycommunitiesweremorelikelytobeexpropriatedinthewake of negative income shocks. Using panel data consisting of 1,366 city-level persecutions of Jews from 936 European cities between 1100 and 1800, we test whether persecutions were more likely in colder growing seasons. A one standard deviation decrease in average growing season temperature increased the probability of a persecution between one-half and one percentage points (relative to a baseline probability of two percent). This effect was strongest in regions with poor soil quality or located within weak states. We argue that long-run decline in violence against Jews between 1500 and 1800 is partly attributable to increases in fiscal and legal capacity across many European states. Key words: Political Economy; State Capacity; Expulsions; Jewish History; Climate JEL classification: N33; N43; Z12; J15; N53 ⇤We are grateful to Megan Teague and Michael Szpindor Watson for research assistance. We benefited from comments from Ran Abramitzky, Daron Acemoglu, Dean Phillip Bell, Pete Boettke, Tyler Cowen, Carmel Chiswick, Melissa Dell, Dan Bogart, Markus Eberhart, James Fenske, Joe Ferrie, Raphäel Franck, Avner Greif, Philip Hoffman, Larry Iannaccone, Remi Jedwab, Garett Jones, James Kai-sing Kung, Pete Leeson, Yannay Spitzer, Stelios Michalopoulos, Jean-Laurent Rosenthal, Naomi Lamoreaux, Jason Long, David Mitch, Joel Mokyr, Johanna Mollerstrom, Robin Mundill, Steven Nafziger, Jared Rubin, Gail Triner, John Wallis, Eugene White, Larry White, and Ekaterina Zhuravskaya. -

The Virtues of a Good Historian in Early Imperial Germany: Georg Waitz’S Contested Example 1

Published in Modern Intellectual History 15 (2018), 681-709. © Cambridge University Press. Online at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1479244317000142 The Virtues of a Good Historian in Early Imperial Germany: Georg Waitz’s Contested Example 1 Herman Paul Recent literature on the moral economy of nineteenth-century German historiography shares with older scholarship on Leopold von Ranke’s methodological revolution a tendency to refer to “the” historical discipline in the third person singular. This would make sense as long as historians occupied a common professional space and/or shared a basic understanding of what it meant to be an historian. Yet, as this article demonstrates, in a world sharply divided over political and religious issues, historians found it difficult to agree on what it meant to be a good historian. Drawing on the case of Ranke’s influential pupil Georg Waitz, whose death in 1886 occasioned a debate on the relative merits of the example that Waitz had embodied, this article argues that historians in early Imperial Germany were considerably more divided over what they called “the virtues of the historian” than has been acknowledged to date. Their most important frame of reference was not a shared discipline but rather a variety of approaches corresponding to a diversity of models or examples (“scholarly personae” in modern academic parlance), the defining features of which were often starkly contrasted. Although common ground beneath these disagreements was not entirely absent, the habit of late nineteenth-century German historians to position themselves between Waitz and Heinrich von Sybel, Ranke and Friedrich Christoph Dahlmann, or other pairs of proper names turned into models of virtue, suggests that these historians experienced their professional environment as characterized primarily by disagreement over the marks of a good historian. -

According to the Liber De Unitate Ecclesiae Conservanda

CHAPTER SIX THE ‘RIGHT ORDER OF THE WORLD’ ACCORDING TO THE LIBER DE UNITATE ECCLESIAE CONSERVANDA Introduction “No one ascends to heaven except for those who come from heaven, the son of man who is in heaven.” With these words, found in the holy gospel, the Lord commanded the unity of the church; united through love and through the unity of its saver, the head of the church, who leads it to heaven.1 This passage, stressing the theme of unity, opens one of the most famous and important tracts in the polemical literature,2 the Liber de unitate ecclesiae conservanda (Ldu) from the early 1090s. By this time, the ponti cate of Urban II (1088–1099) had experienced some rough times.3 The royal side had emerged victorious from the erce struggles of the closing years of Pope Gregory VII’s reign, manifested in the enthronisa- tion of anti-pope Guibert of Ravenna, the sacking of Rome,4 and the crowning of King Henry IV as emperor in 1084.5 Moreover, the death 1 Nemo ascendit in caelum, nisi qui descendit de caelo, lius hominis, qui est in caelo. Per haec sancti euangelii verba commendat Dominus unitatem ecclesiae, quae per caritatem concordans membrorum unitate colligit se in caelum in ipso redemptore, qui est caput ecclesiae (Ldu, 273). 2 Wattenbach and Holtzmann 1967b: 406; Affeldt 1969: 313; Koch 1972: 45; Erdmann 1977: 260. Boshof 1979b: 98; Cowdrey 1998a: 265. 3 The papacy of Urban II has been seen as a continuation of the Gregorian reform project; see Schmale 1961a: 275. -

The Christianization of the Dome of the Rock the Early Years of the Eleventh

CHAPTER FIVE THE CHRISTIANIZATION OF THE DOME OF THE ROCK The early years of the eleventh century have been described as the only period to witness official persecution of Jews and Christians by Muslims during Arab rule in Jerusalem.1 The Fatimid caliph Al-Hakim (996–1021), responsible for the persecution, terrorized Muslims as well. Al-Hakim, known to be deranged, called for the destruction of synagogues and churches, and had the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem razed in 1009.2 How- ever, one year before his death in 1021, this madman changed his attitude and allowed Jews and Christians to rebuild their churches and synagogues. The Jews did not find it easy to rebuild; even the Christians did not com- plete the reconstruction of the Holy Sepulcher until 1048, and then only with the help of Byzantine emperors.3 The destruction initiated by the mad caliph was cited by Pope Urban II decades later when, in 1096, he rallied his warring Frankish knights to avenge the “ruination” of the Christian altars by Muslims in the Holy Land. Though by the 1090s al-Hakim was long dead, and the Holy Sepulcher rebuilt and once again in Christian hands, Urban used the earlier events in service of his desire to quell the civil strife among the western knights. Some months after receiving a plea from Emperor Alexius I to help defend Byzantium from the Seljuk Turks, Urban called upon his knights to cease their greedy, internecine feuds and fight instead to regain control over the Holy Land—to remove the “pollution of paganism” that stained the holy city. -

King of the Danes’ Stephen M

Hamlet with the Princes of Denmark: An exploration of the case of Hálfdan ‘king of the Danes’ Stephen M. Lewis University of Caen Normandy, CRAHAM [email protected] As their military fortunes waxed and waned, the Scandinavian armies would move back and forth across the Channel with some regularity [...] appearing under different names and in different constellations in different places – Neil Price1 Little is known about the power of the Danish kings in the second half of the ninth century when several Viking forces ravaged Frankia and Britain – Niels Lund2 The Anglo-Saxon scholar Patrick Wormald once pointed out: ‘It is strange that, while students of other Germanic peoples have been obsessed with the identity and office of their leaders, Viking scholars have said very little of such things – a literal case of Hamlet without princes of Denmark!’3 The reason for this state of affairs is two-fold. First, there is a dearth of reliable historical, linguistic and archaeological evidence regarding the origins of the so-called ‘great army’ in England, except that it does seem, and is generally believed, that they were predominantly Danes - which of course does not at all mean that they all they came directly from Denmark itself, nor that ‘Danes’ only came from the confines of modern Denmark. Clare Downham is surely right in saying that ‘the political history of vikings has proved controversial due to a lack of consensus as to what constitutes reliable evidence’.4 Second, the long and fascinating, but perhaps ultimately unhealthy, obsession with the legendary Ragnarr loðbrók and his litany of supposed sons has distracted attention from what we might learn from a close and separate examination of some of the named leaders of the ‘great army’ in England, without any inferences being drawn from later Northern sagas about their dubious familial relationships to one another.5 This article explores the case of one such ‘Prince of Denmark’ called Hálfdan ‘king of the Danes’. -

All in the Family: Creating a Carolingian Genealogy in the Eleventh Century*

All in the family: creating a Carolingian genealogy in the eleventh century* Sarah Greer The genre of genealogical texts experienced a transformation across the tenth century. Genealogical writing had always been a part of the Judeo-Christian tradition, but the vast majority of extant genealogies from the continent before the year 1000 are preserved in narrative form, a literary account of the progression from one generation to another. There were plenty of biblical models for this kind of genealogy; the book of Genesis is explicitly structured as a genealogy tracing the generations that descended from Adam and Eve down to Joseph.1 Early medieval authors could directly imitate this biblical structure: the opening sections of Thegan’s Deeds of Louis the Pious, for example, traced the begetting of Charlemagne from St Arnulf; in England, Asser provided a similarly shaped presentation of the genealogia of King Alfred.2 In the late tenth/early eleventh century, however, secular genealogical texts witnessed an explosion of interest. Genealogies of kings began to make their way into narrative historiographical texts with much greater regularity, shaping the way that those histories themselves were structured.3 The number of textual genealogies that were written down increased exponentially and began to move outside of the royal family to include genealogies of noble families in the West Frankish kingdoms and Lotharingia.4 Perhaps most remarkable though, is that these narrative genealogies began – for the first time – to be supplemented by new diagrammatic forms. The first extant genealogical tables of royal and noble families that we possess date from exactly this period, the late tenth and eleventh centuries.5 The earliest forms of these diagrams were relatively plain. -

TEC-1090 Datasheet 5165B

Thermo Electric Cooling Temperature Controller TEC-1090 TEC Controller / Peltier Driver ±16 A / ±19 V OEM Precision TEC Controller General Description The TEC-1090 is a specialized TEC controller / power supply able to precision-drive Peltier elements. It features a true bipolar current source for cooling / heating, two temperature monitoring inputs (1x high precision, 1x auxiliary) and intelligent PID control with auto tuning. The TEC-1090 is fully digitally controlled, its hard- and firmware offer various communication and safety options. The included PC-Software allows configuration, control, monitoring and live diagnosis of the TEC controller via USB and RS485. All parameters are saved to non-volatile memory. Saving can be disabled for bus operation. For the most straightforward applications, only a power supply, a Peltier element and one temperature sensor Features need to be connected to the TEC-1090. After power-up the DC Input Voltage: 12 – 24 V nominal unit will operate according to pre-configured values. (In TEC Controller / Driver: Autonomous Operation stand-alone mode no control interface is needed.) Output Current: 0 to ±16 A, <1.5% Ripple The TEC-1090 can handle Pt100, Pt1000 or NTC (0 to ±10 A available as TEC-1089) temperature probes. For highest precision and stability Output Voltage: 0 to ±19 V (max. U IN - 3.5 V) applications a Pt1000 / 4-wire input configuration is Temp. Sensor Types: Pt100, Pt1000, NTC recommended. (Temperature acquisition circuitry of each Temperature Precision: <0.01 °C individual device is factory-calibrated to ensure optimal accuracy and repeatability.) Temperature Stability: <0.01 °C An auxiliary temperature input allows the connection of an Thermal Power Control: PID, Performance-optimized NTC probe that is located on the heat sink of the Peltier Configuration / Diagnosis: via USB / RS485 (Software) element. -

1 the Frankish Inheritance

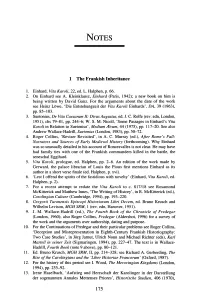

NOTES 1 The Frankish Inheritance I. Einhard, Vita Karoli, 22, ed. L. Halphen, p. 66. 2. On Einhard see A. Kleinklausz, Einhard (Paris, 1942); a new book on him is being written by David Ganz. For the arguments about the date of the work see Heinz Lowe, 'Die Entstehungzeit der Vita Karoli Einhards', DA, 39 (1963), pp. 85-103. 3. Suetonius, De Vita Caesarum II: Divus Augustus, ed. J. C. Rolfe (rev. edn, London, 1951), chs 79-81, pp. 244-6; W. S.M. Nicoll, 'Some Passages in Einhard's Vita Karoli in Relation to Suetonius', Medium JEvum, 44 (1975), pp. 117-20. See also Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, Suetonius (London, 1983), pp. 50--72. 4. Roger Collins, 'Reviser Revisited', in A. C. Murray (ed.), After Rome's Fall: Narrators and Sources of Early Medieval History (forthcoming). Why Einhard was so unusually detailed in his account of Roncesvalles is not clear. He may have had family ties with one of the Frankish commanders killed in the battle, the seneschal Eggihard. 5. Vita Karoli, prologue, ed. Halphen, pp. 2-6. An edition of the work made by Gerward, the palace librarian of Louis the Pious first mentions Einhard as its author in a short verse finale (ed. Halphen, p. xvi). 6. 'Lest I offend the spirits of the fastidious with novelty' (Einhard, Vita Karoli, ed. Halphen, p. 2). 7. For a recent attempt to redate the Vita Karoli to c. 817/18 see Rosamond McKitterick and Matthew Innes, 'The Writing of History', in R. McKitterick (ed.), Carolingian Culture (Cambridge, 1994), pp. 193-220. -

Elite Networks and Courtly Culture in Medieval Denmark Denmark in Europe, 1St to 14Th Centuries

ELITE NETWORKS AND COURTLY CULTURE IN MEDIEVAL DENMARK DENMARK IN EUROPE, 1ST TO 14TH CENTURIES _______________ A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston _______________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________ By Maria R. D. Corsi May, 2014 . ELITE NETWORKS AND COURTLY CULTURE IN MEDIEVAL DENMARK DENMARK IN EUROPE, 1ST TO 14TH CENTURIES _________________________ Maria R. D. Corsi APPROVED: _________________________ Sally N. Vaughn, Ph.D. Committee Chair _________________________ Frank L. Holt, Ph.D. _________________________ Kairn A. Klieman, Ph.D. _________________________ Michael H. Gelting, Ph.D. University of Aberdeen _________________________ John W. Roberts, Ph.D. Dean, College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences Department of English ii ELITE NETWORKS AND COURTLY CULTURE IN MEDIEVAL DENMARK DENMARK IN EUROPE, 1ST TO 14TH CENTURIES _______________ An Abstract of a Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston _______________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________ By Maria R.D. Corsi May, 2014 ABSTRACT This dissertation advances the study of the cultural integration of Denmark with continental Europe in the Middle Ages. By approaching the question with a view to the longue durée, it argues that Danish aristocratic culture had been heavily influenced by trends on the Continent since at least the Roman Iron Age, so that when Denmark adopted European courtly culture, it did so simultaneously to its development in the rest of Europe. Because elite culture as it manifested itself in the Middle Ages was an amalgamation of that of Ancient Rome and the Germanic tribes, its origins in Denmark is sought in the interactions between the Danish territory and the Roman Empire.