Between Ideology and Utopia. Recent Discussions on John Paul II's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3Rd Sunday in Ordinary Time-Year B 24Th January 2021

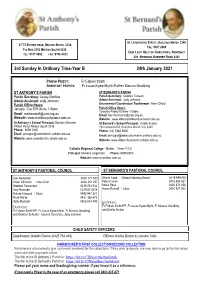

61 LERDERDERG STREET, BACCHUS MARSH 3340 67-75 EXFORD ROAD, MELTON SOUTH, 3338. TEL: 5367 2069 P.O BOX 2152 MELTON SOUTH 3338 OUR LADY HELP OF CHRISTIANS, KOROBEIT TEL: 9747 9692 FAX: 9746 0422 309 MYRNIONG-KOROBEIT ROAD 3341 3rd Sunday In Ordinary Time-Year B 24th January 2021 PARISH PRIEST: Fr Fabian Smith ASSISTANT PRIESTS: Fr Lucas Kyaw Myint /Father Marcus Goulding ST ANTHONY’S PARISH ST BERNARD’S PARISH Parish Secretary: Lesley Morffew Parish Secretary: Dolores Turcsan Admin Assistant: Judy Johnson Admin Assistant: Judy Johnson Parish Office Hours: Sacramental Coordinator/ Bookkeeper: Naim Chdid January :Tue-Fri9.00am-1.00pm Parish Office Hours: Tuesday-Friday 9.00am-1.00pm Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Website: www.stanthonyof padua.com.au Website: www.stbernardsbacchusmarsh.com.au St Anthony’s School Principal: Damien Schuster St Bernard’s School Principal: Emilio Scalzo Wilson Road, Melton South 3338 19a Gisborne Rd, Bacchus Marsh VIC 3340 Phone: 8099 7800 Phone: (03) 5366 5800 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Website: www.sameltonsth.catholic.edu.au Website: www.sbbacchusmarsh.catholic.edu.au Catholic Regional College - Melton (Years 7-12) Principal: Marlene Jorgensen Phone: 8099 6000 Website: www.crcmelton.com.au ST ANTHONY’S PASTORAL COUNCIL ST BERNARD’S PASTORAL COUNCIL Sue Alexander 0400 171 843 Shane Cook -School Advisory Board 0419 999 052 Lillian Christian - Vice Chair 0400 441 257 Peter Farren 0418 594 501 Stephen Fernandes 0439 -

The Holy See

The Holy See SOLEMNITY OF THE IMMACULATE CONCEPTION OF THE BLESSED VIRGIN MARY JOHN PAUL II ANGELUS Wednesday, 8 December 2004 1. Tota pulchra es, Maria! On 8 December 1854, 150 years ago, Bl. Pius IX proclaimed the Dogma of the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary. The privilege of being preserved free from original sin means that she was the first to be redeemed by her Son. Her sublime beauty, which mirrors that of Christ, is for all believers a pledge of the victory of divine Grace over sin and death. 2. The Immaculate Conception shines like a beacon of light for humanity in all the ages. At the beginning of the third millennium, it guides us to believe and hope in God, in his salvation and in eternal life. In particular, it lights the way of the Church, which is committed to the new evangelization. 3. This afternoon, in my traditional tribute to the Blessed Virgin in Piazza di Spagna, I will entrust the city of Rome and the whole world to her, the Immaculate Mother of the Word made Man. Let us now pray for her powerful intercession with filial trust as we recite the Angelus. After the recitation of the Angelus, the Holy Father said: Yesterday evening in Mossul, Iraq, an Armenian Apostolic Church and the Chaldean Archbishop's 2 residence were destroyed. I express my spiritual closeness to the faithful, deeply distressed by the attack, and I pray the Lord through the intercession of the Immaculate Virgin that the Iraqi People may at last experience a time of reconciliation and peace. -

The Holy See

The Holy See ADDRESS OF JOHN PAUL II TO THE PLENARY ASSEMBLY OF THE PONTIFICAL COMMISSION FOR SOCIAL COMMUNICATIONS March 4, 1999 Your Eminences, Your Excellencies, Dear Brothers and Sisters in Christ, I am happy to welcome you, the members, consultors, experts and staff of the Pontifical Council for Social Communications on the occasion of your Plenary Assembly. I greet especially Cardinal Andrzej Maria Deskur, President Emeritus of the Council, and Archbishop John Foley, his successor as President. I am grateful for the presence as well of Cardinal Eugenio de Araujo Sales and Cardinal Hyacinthe Thiandoum, who have contributed so much to the work of the Council from its earliest days. This year marks the thirty-fifth anniversary of the document In Fructibus Multis, which responded to the request of the Fathers of the Second Vatican Council that the Holy See establish a special commission for social communications: thus, a founding document of your Pontifical Council. The Fathers saw clearly that if there was to be a genuine colloquium salutis between the Church and the world, then a prime place had to be given to the use of the media, which were growing in sophistication and scope at the time of the Council and which have become still more influential in our own day. This is also the twenty-fifth year of one of your Council’s best-known initiatives, the telecast of the Christmas Midnight Mass from Saint Peter’s Basilica, now one of the most widely followed religious programmes in the world. I am truly grateful to all who contribute to this and other such broadcasts, which are an admirable service of the proclamation of the word of God and a particular help to the Successor of Peter in his universal ministry of truth and unity. -

February 10, 2017 Vol

Sharing the Gospel Missionary to Ireland has ‘love for helping youth know Christ,’ page 9. Serving the Church in Central and Southern Indiana Since 1960 CriterionOnline.com February 10, 2017 Vol. LVII, No. 17 75¢ Pastoral needs Building a bridge assessment will help introduce archdiocese to new shepherd By Sean Gallagher Catholics across central and southern Indiana are waiting for Pope Francis to appoint a new shepherd. To prepare for his arrival, archdiocesan Catholics are being given the opportunity to give him a clear and detailed portrait of the archdiocese and to express their hopes for its future. This will happen through See story the creation of a pastoral in Spanish, needs assessment of the page 2. Archdiocese of Indianapolis. The assessment was commissioned by Cardinal Joseph W. Tobin, archbishop of Indianapolis from 2012-16 in the days before he was installed on Jan. 6 as archbishop of Newark, N.J. It will involve interviews of 25-30 people from across the archdiocese, several listening sessions attended by dozens of clergy, religious and lay Catholics, and an online survey that all archdiocesan Catholics can fill out. St. Philip Neri first-grader Suzet Cruz, left, and St. Jude first-grader Grace Denney proudly show the cut-out hearts they decorated with their hand prints Washington-based consulting firm GP on Feb. 1, the day when students from both Indianapolis schools came together to share their faith and learn from each other. (Photo by John Shaughnessy) Catholic Services will conduct the assessment. Daniel Conway, senior vice president for the firm and a member of the editorial board of Schools cross boundaries and comfort zones The Criterion, will oversee the process. -

The Holy See

The Holy See MESSAGE OF JOHN PAUL II TO THE PLENARY ASSEMBLY OF THE PONTIFICAL COUNCIL FOR SOCIAL COMMUNICATIONS 1. This is a significant year for the Pontifical Council for Social Communications, for it marks the fiftieth anniversary of the establishment by my predecessor Pope Pius XII of the Pontifical Commission for Educational and Religious Films. In the years after the Second Vatican Council the Commission served as a clear sign of the Church's increased involvement in the world of social communications and her recognition of the immense influence of the modern media in the life of society. Finally, ten years ago, with the promulgation of the Apostolic Constitution Pastor Bonus, the Commission was raised to the status of a Pontifical Council. Each of these steps corresponded not only to the ever greater momentum of the communications revolution, but also to the Church's increasing recognition of the role of the communications media in her mission, as an instrument and as a field of evangelization. In greeting you, I greet all of those whom you represent, the many who have served over the years on the Pontifical Commission and now the Pontifical Council for Social Communications. With special affection, I greet Cardinal Andrzej Maria Deskur, your President Emeritus, who had a part in much of the history of the Council, and Archbishop John P. Folev, whose dedication you all know. 2. In more recent years, the communications revolution has continued its rapid advance. Today in fact we find ourselves facing an immense challenge, since technology often seems to be moving at such a speed that we can no longer control where it might be leading us. -

The Holy See

The Holy See MESSAGE OF JOHN PAUL II TO THE PLENARY ASSEMBLY OF THE PONTIFICAL COMMISSION FOR SOCIAL COMMUNICATIONS 1. This is a significant year for the Pontifical Council for Social Communications, for it marks the fiftieth anniversary of the establishment by my predecessor Pope Pius XII of the Pontifical Commission for Educational and Religious Films. In the years after the Second Vatican Council the Commission served as a clear sign of the Church's increased involvement in the world of social communications and her recognition of the immense influence of the modern media in the life of society. Finally, ten years ago, with the promulgation of the Apostolic Constitution Pastor Bonus, the Commission was raised to the status of a Pontifical Council. Each of these steps corresponded not only to the ever greater momentum of the communications revolution, but also to the Church's increasing recognition of the role of the communications media in her mission, as an instrument and as a field of evangelization. In greeting you, I greet all of those whom you represent, the many who have served over the years on the Pontifical Commission and now the Pontifical Council for Social Communications. With special affection, I greet Cardinal Andrzej Maria Deskur, your President Emeritus, who had a part in much of the history of the Council, and Archbishop John P. Folev, whose dedication you all know. 2. In more recent years, the communications revolution has continued its rapid advance. Today in fact we find ourselves facing an immense challenge, since technology often seems to be moving at such a speed that we can no longer control where it might be leading us. -

February 3, 2017 Vol

It’s All Good Big hearts have room for many friends, writes columnist Patti Lamb, page 12. Serving the Church in Central and Southern Indiana Since 1960 CriterionOnline.com February 3, 2017 Vol. LVII, No. 16 75¢ President’s action banning refugees brings outcry from Church leaders WASHINGTON (CNS)—President Donald J. Trump’s executive memorandum intended to restrict the entry of terrorists coming to the United States brought an outcry from Catholic leaders across the U.S. Church leaders used phrases such as “devastating,” “chaotic” and “cruel” to describe the Jan. 27 action that left already-approved David Bethuram refugees and immigrants stranded at U.S. airports and led the Department of Homeland Security to rule that green card holders—lawful permanent U.S. residents—be allowed into the country. “The executive order to turn away refugees and to close our nation to those, particularly Muslims, fleeing violence, oppression and persecution is contrary to both Catholic and American values,” said Pro-life advocates with the Indiana State Knights of Columbus carry a banner past the U.S. Capitol Building on Jan. 27 during the annual March for Life Chicago Cardinal Blase J. Cupich in a in Washington. (CNS photo/Leslie E. Kossoff) Jan. 29 statement. “The Protection of the Nation From Foreign Terrorist Entry Into the United Archdiocesan youths show their courage by States,” which suspends the entire U.S. refugee resettlement program for marching, standing up for life in America 120 days, bans entry from all citizens of seven majority-Muslim countries—Syria, By John Shaughnessy on Twitter about the impact the march has Iraq, Iran, Sudan, Libya, Yemen and had in their lives. -

DOLENTIUM HOMINUM No

DOLENTIUM HOMINUM No. 32 – Eleventh Year (No. 2) 1996 JOURNAL OF THE PONTIFICAL COUNCIL FOR PASTORAL ASSISTANCE TO HEALTH CARE WORKERS Editorial and Business Offices: Editor: Vatican City FIORENZO CARDINAL ANGELINI Telephone: 6988–3138, 6988–4720, 6988–4799, Telefax: 6988–3139 Telex: 2031 SANITPC VA Executive Editor: REV.JOSÉ L. REDRADO O.H. Cover: Glass window by Fr. Costantino Ruggeri Associate Editor: REV.FELICE RUFFINI M.I. Published three times a year Editorial Board: FR. GIOVANNI D’ERCOLE F.D.P. Subscription rate: one year Lire 60.000 SR. CATHERINE DWYER M.M.M. (or the equivalent in local currency) DR. GIOVANNI FALLANI postage included MSGR. JESUS IRIGOYEN FR. VITO MAGNO R.C.I. ING. FRANCO PLACIDI PROF. GOTTFRIED ROTH MSGR. ITALO TADDEI Printed by Editrice VELAR S.p.A., Gorle (BG) Editorial Staff: FR. DAVID MURRAY M.ID. DR MARÍA ÁNGELES CABANA M.ID. Spedizione in abb. postale Comma 27 art. 2 legge 549/95 - Roma SR. MARIE-GABRIEL MULTIER FR. JEAN-MARIE M. MPENDAWATU Contents 4 PONTIFICAL APPOINTMENTS 53 Aren’t I Your Health? Rev. Jorge A. Palencia EDITORIAL 58 Celebrations at the Sanctuary 7 The Care of the Sick in the Postsynodal of Our Lady of Guadalupe Document Vita Consecrata Fiorenzo Cardinal Angelini 58 Holy Mary: Queen and Mother of Mercy Fiorenzo Cardinal Angelini MAGISTERIUM 59 Let the Young Look to Christ 11 Addresses by the Holy Father, Fiorenzo Cardinal Angelini John Paul II 61 To Follow Christ in Keeping with Mary’s Example TOPICS 63 I Go in Spirit to Guadalupe 2 18 The Health Ministry: to Celebrate the Day of the Sick A Challenge for Training John Paul II Professor Francisco Alvarez 64 Cardinal Angelini’s Greeting 27 Suffering in Illness. -

Elementos De Historia, Teoría, Doctrina Y Práctica Del Derecho Canónico Pluriconfesional

ELEMENTOS DE HISTORIA, TEORÍA, DOCTRINA Y PRÁCTICA DEL DERECHO CANÓNICO PLURICONFESIONAL LA ENSEÑANZA DEL DERECHO CANÓNICO EN LAS UNIVERSIDADES PÚBLICAS ESPAÑOLAS Joaquín MANTECÓN SANCHO Para citar este artículo puede utilizarse el siguiente formato: Joaquín Mantecón Sancho (2016): “La enseñanza del Derecho canónico en las universidades públicas españolas”, en Kritische Zeitschrift für überkonfessionelles Kirchenrecht, n.o 3 (2016), pp. 119-134. En línea puede leerse esta noticia en: http://www.eumed.net/rev/rcdcp/03/jms.pdf RESUMEN: Resumen de las enseñanzas actuales del Derecho canónico en España en algunas Universidades públicas nacionales, excluyendo las privadas, pero no recogiendo tampoco las concordatarias, generalmente más propicias a que el Derecho canónico aparezca entre sus enseñanzas. Defensa del Derecho canónico, pero no del Derecho eclesiástico. El autor se circunscribe a la doctrina exclusivamente española y patentiza la antigüedad de los manuales de Derecho canónico editados en España. PALABRAS CLAVE: Derecho canónico, Derecho matrimonial canónico, Teología moral, Instituciones eclesiásticas, Planes de estudio, Rechazo del Derecho cánonico, Derecho eclesiástico del Estado. 1. Presencia histórica del Derecho Canónico en la Universidad española España, el Derecho Canónico ha figurado siempre en los planes de estudio de la carrera de Derecho desde que se implanta el nuevo modelo de Universidad pública al estilo napoleónico. Y esto ha sido así incluso durante los períodos en los que la política del Gobierno ha tenido un claro carácter antirreligioso o anticlerical, como sucedió en la etapa posterior a la revolución de 1868 (La Gloriosa), y durante la II República1. Así pues, el Ministerio de Instrucción Pública de la II República –nada sospechoso de tentaciones confesionalistas–, decidió mantener esta disciplina en los nuevos planes docentes universitarios. -

PRCUA Naród Polski

Get a 10% DISCOUNT on Life PRCUA Represented at Polish Folk Dance Festival in Rzeszow Insurance Premiums with PRCUA’s Read Resident V.P. Anna Sokolowski’s Report documenting the trip that she and President and Mrs. Joseph A. Family Life Insurance Plan Special Drobot, Jr. made to Poland to attend the International Polish YOU determine the definition of Folk Dance Festival in Rzeszow, Poland. Choreographers from “Family” - any 2 related persons who are several PRCUA dance groups were at the Festival and the medically qualified will be considered a PRCUA is proud of Wesoly Lud Polish Folk Dance Ensemble “family”... see details on PAGE 3 and Polonia Ensemble for representing us at the Fesitval. PAGES 7 and 13 Naród Polski Polish Nation Bi-lingual Publication of the Polish Roman Catholic Union of America - A Fraternal Benefit Society Safeguarding Your Future with Life Insurance & Annuities. www.PRCUA.org October 1, 2011 - 1 pazdziernika 2011 No. 10 - Vol. CXXV Fly your Polish 115th Anniversary of Naród Polski and American The Polish Roman members in Detroit know what's going on from the members Catholic Union of in Philadelphia. It is the tie that binds us all together as one flags during America celebrated the body, one organization. It is the face that our fraternal 115th anniversary of its presents to the general public. It is a means by which our October - Polish Narod Polski news- Polish customs and traditions are shared among our members paper with an Exhibit and friends. The Narod Polski is all of that and more. It is all of American at the Polish Museum us who cherish and hold dear our Polish roots, customs and of America, 984 N. -

The Holy See

The Holy See SOLEMNITY OF THE IMMACULATE CONCEPTION OF THE BLESSED VIRGIN MARY BENEDICT XVI ANGELUS St Peter's Square Tuesday, 8 December 2009 (Video) Dear Brothers and Sisters, On 8 December we celebrate one of the most beautiful Feasts of the Blessed Virgin Mary: the Solemnity of the Immaculate Conception. But what does Mary being "Immaculate" mean? And what does this title tell us? First of all let us refer to the biblical texts of today's Liturgy, especially the great "fresco" of the third chapter of the Book of Genesis and the account of the Annunciation in the Gospel according to Luke. After the original sin, God addresses the serpent, which represents Satan, curses it and adds a promise: "I will put enmity between you and the woman, and between your seed and her seed; he shall bruise your head, and you shall bruise his heel" (Gn 3: 15). It is the announcement of revenge: at the dawn of the Creation, Satan seems to have the upper hand, but the son of a woman is to crush his head. Thus, through the descendence of a woman, God himself will triumph. Goodness will triumph. That woman is the Virgin Mary of whom was born Jesus Christ who, with his sacrifice, defeated the ancient tempter once and for all. This is why in so many paintings and statues of the Virgin Immaculate she is portrayed in the act of crushing a serpent with her foot. Luke the Evangelist, on the other hand, shows the Virgin Mary receiving the Annunciation of the heavenly Messenger (cf. -

ANDRZEJ MARIA MICHAŁ DESKUR Anna M

Kritische Zeitschrift für überkonfessionelles Kirchenrecht Revista crítica de Derecho Canónico Pluriconfesional Rivista critica di diritto canonico molticonfessionale ANDRZEJ MARIA MICHAŁ DESKUR Anna M. SOLARZ Para citar este artículo puede utilizarse el siguiente formato: Anna Marcin Solarz (2016): “Andrzej Maria Michał Deskur”, en Kritische Zeitschrift für überkonfessionelles Kirchenrecht, n.º 3 (diciembre de 2016), pp. 154-159. En línea puede leerse la presente nota en su versión inglesa en el sitio: http://www.eumed.net/rev/rcdcp/03/.ams.pdf. RESUMEN: Semblanza biográfica del cardenal Andrzej Maria Deskur escrita por Anna Marcin Solarz, docente del Instituto de Estudios Internacionales de la Universidad de Varsovia, donde está especializada en Relaciones entre la Iglesia y el Estado. La personalidad desbordante de Deskur se vio afectada por una enfermedad que lo capitidiminuyó durante mucho tiempo y que le redujo a moverse en una silla de ruedas. PALABRAS CLAVE: Juan Pablo II, Andrzej Maria Deskur, Stanisława Kossecka, Pierre Gerliera, Adam Sapieha, Gaudium et spes, Juan XXIII, Pablo VI. Born on 29 February 1924 in Sancygniów, died on 3 September 2011, in the Vatican, buried on 12 September 2011 in the Sanctuary of St. John Paul II in Łagiewniki. Andrzej Maria Deskur came from the Polish branch of a French family Descours, distinguished in the history of Poland and ennobled in 1764. The great-grandfather of Andrzej was exiled to Siberia twice. His grandson, Andrzej as well, the father of the later cardinal, married Stanisława Kossecka, who gave birth to four of his sons (Jozef Maria, Andrzej Maria, Stanislaw Maria, and Antoni Maria) and a daughter ‒ Wanda.