© 2013 Philip M. Longo ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

China in 50 Dishes

C H I N A I N 5 0 D I S H E S CHINA IN 50 DISHES Brought to you by CHINA IN 50 DISHES A 5,000 year-old food culture To declare a love of ‘Chinese food’ is a bit like remarking Chinese food Imported spices are generously used in the western areas you enjoy European cuisine. What does the latter mean? It experts have of Xinjiang and Gansu that sit on China’s ancient trade encompasses the pickle and rye diet of Scandinavia, the identified four routes with Europe, while yak fat and iron-rich offal are sauce-driven indulgences of French cuisine, the pastas of main schools of favoured by the nomadic farmers facing harsh climes on Italy, the pork heavy dishes of Bavaria as well as Irish stew Chinese cooking the Tibetan plains. and Spanish paella. Chinese cuisine is every bit as diverse termed the Four For a more handy simplification, Chinese food experts as the list above. “Great” Cuisines have identified four main schools of Chinese cooking of China – China, with its 1.4 billion people, has a topography as termed the Four “Great” Cuisines of China. They are Shandong, varied as the entire European continent and a comparable delineated by geographical location and comprise Sichuan, Jiangsu geographical scale. Its provinces and other administrative and Cantonese Shandong cuisine or lu cai , to represent northern cooking areas (together totalling more than 30) rival the European styles; Sichuan cuisine or chuan cai for the western Union’s membership in numerical terms. regions; Huaiyang cuisine to represent China’s eastern China’s current ‘continental’ scale was slowly pieced coast; and Cantonese cuisine or yue cai to represent the together through more than 5,000 years of feudal culinary traditions of the south. -

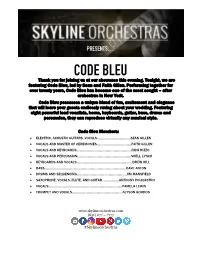

CODE BLEU Thank You for Joining Us at Our Showcase This Evening

PRESENTS… CODE BLEU Thank you for joining us at our showcase this evening. Tonight, we are featuring Code Bleu, led by Sean and Faith Gillen. Performing together for over twenty years, Code Bleu has become one of the most sought – after orchestras in New York. Code Bleu possesses a unique blend of fun, excitement and elegance that will leave your guests endlessly raving about your wedding. Featuring eight powerful lead vocalists, horns, keyboards, guitar, bass, drums and percussion, they can reproduce virtually any musical style. Code Bleu Members: • ELECTRIC, ACOUSTIC GUITARS, VOCALS………………………..………SEAN GILLEN • VOCALS AND MASTER OF CEREMONIES……..………………………….FAITH GILLEN • VOCALS AND KEYBOARDS..…………………………….……………………..RICH RIZZO • VOCALS AND PERCUSSION…………………………………......................SHELL LYNCH • KEYBOARDS AND VOCALS………………………………………..………….…DREW HILL • BASS……………………………………………………………………….….......DAVE ANTON • DRUMS AND SEQUENCING………………………………………………..JIM MANSFIELD • SAXOPHONE, VOCALS, FLUTE, AND GUITAR….……………ANTHONY POLICASTRO • VOCALS………………………………………………………………….…….PAMELA LEWIS • TRUMPET AND VOCALS……………….…………….………………….ALYSON GORDON www.skylineorchestras.com (631) 277 – 7777 #Skylineorchestras DANCE : BURNING DOWN THE HOUSE – Talking Heads BUST A MOVE – Young MC A GOOD NIGHT – John Legend CAKE BY THE OCEAN – DNCE A LITTLE LESS CONVERSATION – Elvis CALL ME MAYBE – Carly Rae Jepsen A LITTLE PARTY NEVER KILLED NOBODY – Fergie CAN’T FEEL MY FACE – The Weekend A LITTLE RESPECT – Erasure CAN’T GET ENOUGH OF YOUR LOVE – Barry White A PIRATE LOOKS AT 40 – Jimmy Buffet CAN’T GET YOU OUT OF MY HEAD – Kylie Minogue ABC – Jackson Five CAN’T HOLD US – Macklemore & Ryan Lewis ACCIDENTALLY IN LOVE – Counting Crows CAN’T HURRY LOVE – Supremes ACHY BREAKY HEART – Billy Ray Cyrus CAN’T STOP THE FEELING – Justin Timberlake ADDICTED TO YOU – Avicii CAR WASH – Rose Royce AEROPLANE – Red Hot Chili Peppers CASTLES IN THE SKY – Ian Van Dahl AIN’T IT FUN – Paramore CHEAP THRILLS – Sia feat. -

Digital Adaptions of the Scores for Cage Variations I, II and III

Edith Cowan University Research Online ECU Publications 2012 1-1-2012 Digital adaptions of the scores for Cage Variations I, II and III Lindsay Vickery Catherine Hope Edith Cowan University Stuart James Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ecuworks2012 Part of the Music Commons Vickery, L. R., Hope, C. A., & James, S. G. (2012). Digital adaptions of the scores for Cage Variations I, II and III. Proceedings of International Computer Music Conference. (pp. 426-432). Ljubljana. International Computer Music Association. Available here This Conference Proceeding is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ecuworks2012/165 NON-COCHLEAR SOUND _ I[M[2012 LJUBLJANA _9.-14. SEP'l'EMBER Digital adaptions of the scores for Cage Variations I, II and III Lindsay Vickery, Cat Hope, and Stuart James Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts, Edith Cowan University ABSTRACT Over the ten years from 1958 to 1967, Cage revisited to the Variations series as a means of expanding his Western Australian new music ensemble Decibel have investigation not only of nonlinear interaction with the devised a software-based tool for creating realisations score but also of instrumentation, sonic materials, the of the score for John Cage's Variations I and II. In these performance space and the environment The works works Cage had used multiple transparent plastic sheets chart an evolution from the "personal" sound-world of with various forms of graphical notation, that were the performer and the score, to a vision potentially capable of independent positioning in respect to one embracing the totality of sound on a global scale. -

Introduction to the Modern Calculus of Variations

MA4G6 Lecture Notes Introduction to the Modern Calculus of Variations Filip Rindler Spring Term 2015 Filip Rindler Mathematics Institute University of Warwick Coventry CV4 7AL United Kingdom [email protected] http://www.warwick.ac.uk/filiprindler Copyright ©2015 Filip Rindler. Version 1.1. Preface These lecture notes, written for the MA4G6 Calculus of Variations course at the University of Warwick, intend to give a modern introduction to the Calculus of Variations. I have tried to cover different aspects of the field and to explain how they fit into the “big picture”. This is not an encyclopedic work; many important results are omitted and sometimes I only present a special case of a more general theorem. I have, however, tried to strike a balance between a pure introduction and a text that can be used for later revision of forgotten material. The presentation is based around a few principles: • The presentation is quite “modern” in that I use several techniques which are perhaps not usually found in an introductory text or that have only recently been developed. • For most results, I try to use “reasonable” assumptions, not necessarily minimal ones. • When presented with a choice of how to prove a result, I have usually preferred the (in my opinion) most conceptually clear approach over more “elementary” ones. For example, I use Young measures in many instances, even though this comes at the expense of a higher initial burden of abstract theory. • Wherever possible, I first present an abstract result for general functionals defined on Banach spaces to illustrate the general structure of a certain result. -

Immigration and Restaurants in Chicago During the Era of Chinese Exclusion, 1893-1933

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations Summer 2019 Exclusive Dining: Immigration and Restaurants in Chicago during the Era of Chinese Exclusion, 1893-1933 Samuel C. King Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Recommended Citation King, S. C.(2019). Exclusive Dining: Immigration and Restaurants in Chicago during the Era of Chinese Exclusion, 1893-1933. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/5418 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Exclusive Dining: Immigration and Restaurants in Chicago during the Era of Chinese Exclusion, 1893-1933 by Samuel C. King Bachelor of Arts New York University, 2012 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2019 Accepted by: Lauren Sklaroff, Major Professor Mark Smith, Committee Member David S. Shields, Committee Member Erica J. Peters, Committee Member Yulian Wu, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Abstract The central aim of this project is to describe and explicate the process by which the status of Chinese restaurants in the United States underwent a dramatic and complete reversal in American consumer culture between the 1890s and the 1930s. In pursuit of this aim, this research demonstrates the connection that historically existed between restaurants, race, immigration, and foreign affairs during the Chinese Exclusion era. -

John Cage's Entanglement with the Ideas Of

JOHN CAGE’S ENTANGLEMENT WITH THE IDEAS OF COOMARASWAMY Edward James Crooks PhD University of York Music July 2011 John Cage’s Entanglement with the Ideas of Coomaraswamy by Edward Crooks Abstract The American composer John Cage was famous for the expansiveness of his thought. In particular, his borrowings from ‘Oriental philosophy’ have directed the critical and popular reception of his works. But what is the reality of such claims? In the twenty years since his death, Cage scholars have started to discover the significant gap between Cage’s presentation of theories he claimed he borrowed from India, China, and Japan, and the presentation of the same theories in the sources he referenced. The present study delves into the circumstances and contexts of Cage’s Asian influences, specifically as related to Cage’s borrowings from the British-Ceylonese art historian and metaphysician Ananda K. Coomaraswamy. In addition, Cage’s friendship with the Jungian mythologist Joseph Campbell is detailed, as are Cage’s borrowings from the theories of Jung. Particular attention is paid to the conservative ideology integral to the theories of all three thinkers. After a new analysis of the life and work of Coomaraswamy, the investigation focuses on the metaphysics of Coomaraswamy’s philosophy of art. The phrase ‘art is the imitation of nature in her manner of operation’ opens the doors to a wide- ranging exploration of the mimesis of intelligible and sensible forms. Comparing Coomaraswamy’s ‘Traditional’ idealism to Cage’s radical epistemological realism demonstrates the extent of the lack of congruity between the two thinkers. In a second chapter on Coomaraswamy, the extent of the differences between Cage and Coomaraswamy are revealed through investigating their differing approaches to rasa , the Renaissance, tradition, ‘art and life’, and museums. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/27/2021 04:53:00AM This Is an Open Access Chapter Distributed Under the Terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL FOR HISTORY, CULTURE AND MODERNITY www.history-culture-modernity.org Published by: Amsterdam University Press The Cinematic Depiction of Conflict Resolution in the Immigrant Chinese1 Family The Wedding Banquet and Saving Face Qijun Han HCM 1 (2): 129–159 DOI: 10.5117/HCM2013.2.HAN Abstract Both emphasising dilemmas that have been confronted by the Chinese- American family, Ang Lee’s The Wedding Banquet (1993) and Alice Wu’s Saving Face (2004) highlight the image of homosexuality as incompatible with traditional Chinese family values. Through detailed narrative analyses of these two films with a focus on the structure of the plot, the key characters, and camera work, this article aims to answer the questions of how traditional Chinese culture continues to play into and conflict with the experiences of modern Chinese American families and how each film presents and resolves the tensions arising from a culture in transition. The article argues that the importance of studying the ways in which the protagonists try to come to terms with incompatible value systems, lies in the capacity of film to reveal the complex negotiation between tradition and modernity, as well as the socio-cultural specificity of the conceptions of modernity. Keywords: Chinese-American family, homosexuality, narrative analysis, traditional Chinese family values Introduction From the mid-1980s onwards, a large number of filmmakers from Mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and the United States have expanded the vis- ibility of Chinese-American family life. In particular, conflict between members of immigrant Chinese families has been a recurrent theme for HCM 2013, VOL. -

LIFEISLIKE Secured.Pdf

By Flip Kobler and Finn Kobler © Copyright 2018, Pioneer Drama Service, Inc. Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that a royalty must be paid for every performance, whether or not admission is charged. All inquiries regarding rights should be addressed to Pioneer Drama Service, Inc., PO Box 4267, Englewood, CO 80155. All rights to this play—including but not limited to amateur, professional, radio broadcast, television, motion picture, public reading and translation into foreign languages—are controlled by Pioneer Drama Service, Inc., without whose permission no performance, reading or presentation of any kind in whole or in part may be given. These rights are fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America and of all countries covered by the Universal Copyright Convention or with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations, including Canada, Mexico, Australia and all nations of the United Kingdom. ONE SCRIPT PER CAST MEMBER MUST BE PURCHASED FOR PRODUCTION RIGHTS. COPYING OR DISTRIBUTING ALL OR ANY PART OF THIS BOOK WITHOUT PERMISSION IS STRICTLY FORBIDDEN BY LAW. On all programs, printing and advertising, the following information must appear: 1. The full name of the play 2. The full name of the playwrights 3. The following notice: “Produced by special arrangement with Pioneer Drama Service, Inc., Denver, Colorado” For preview only LIFE IS LIKE A DOUBLE CHEESEBURGER COSTUMES Characters wear modern attire appropriate for their situation, whether By Flip Kobler and Finn Kobler a formal night out or a casual dinner with the family. Some specific CAST OF CHARACTERS needs are as follows: # of lines EVAN, JACKSON, and DALE wear mortar boards and graduation robes The Tomato in “Salad Days, Part One.” In Part Three, they wear tuxedos. -

Pat Benatar & Neil Giraldo “We Live for Love” Tour

October 24, 2016 Media Contact: Savannah Whaley Pierson Grant Public Relations 954-776-1999 ext. 225 Jan Goodheart, Broward Center 954-765-5814 PAT BENATAR & NEIL GIRALDO “WE LIVE FOR LOVE” TOUR FORT LAUDERDALE – A rule-breaker and a trail-blazer, Pat Benatar remains a bold and distinctive artist both on stage and on record. She will be performing with her husband and musical collaborator, guitarist Neil Giraldo, at the Broward Center for the Performing Arts when the “We Live For Love” tour comes to the Au-Rene Theater on Wednesday, November 2 at 8 p.m. The Grammy Award–winning powerhouse duo will rock with the signature Benatar sound and Top 10 hits, including “Hit Me With Your Best Shot,” “Love Is a Battlefield,” “We Belong” and “Invincible.” With her unprecedented wins of four consecutive Grammy Awards between 1980 and 1983, as well as three American Music Awards, Benatar is acknowledged as the leading female rock vocalist of the ‘80s, when she also had two RIAA-certified Multi-Platinum albums, five RIAA-certified Platinum albums, three RIAA-certified Gold albums and 19 Top 40 singles. Giraldo has been a professional musician, producer, arranger and songwriter for over four decades with an impressive back catalog that includes more than 100 songs written, produced, arranged and recorded for Benatar, as well as many hits he helped create for John Waite, Rick Springfield (Number One, Grammy-winning classic “Jessie’s Girl” and Top Ten hit “I’ve Done Everything For You” included), Kenny Loggins (Top Twenty hit “Don’t Fight It” – also Grammy-nominated), Steve Forbert, The Del Lords, Beth Hart and countless others. -

'Seinfeld' Credo

DOW JONES, A NEWS CORP COMPANY Nikkei 23249.95 0.00% ▲ Hang Seng 25182.15 0.19% ▼ U.S. 10 Yr 1/32 Yield 0.713% ▲ Crude Oil 42.31 0.17% ▲ Yen 106.96 0.03% ▲ DJIA 27896.72 0.29% ▼ The Wall Street Journal John Kosner English Edition Print Edition Video Podcasts Latest Headlines Home World U.S. Politics Economy Business Tech Markets Opinion Life & Arts Real Estate WSJ. Magazine Search 15-Year Fixed 2.25% 2.46% APR Refinance Rates the Lowest in History 30-Year Fixed 2.50% 2.71% APR 2.46% 5/1 ARM 2.63% 2.90% APR APR $225,000 (5/1 ARM) $904/mo 2.90% APR Calculate Payment $350,000 (5/1 ARM) $1,409/mo 2.79% APR Terms & Conditions apply. NMLS#1136 BOOKS | BOOKSHELF SHARE FACEBOOKNo Hugging, No Learning: The ‘Seinfeld’ Credo TWITTERThe show was assigned to an NBC executive who had never overseen a sitcom. Left alone, Larry David sought inspiration from the only available source: memories of misbegotten moments in his own past. EMAIL PERMALINK PHOTO: NBC/GETTY IMAGES By Edward Kosner Updated Aug. 12, 2016 4:30 pm ET SAVE PRINT TEXT 82 Everyone has a favorite episode or moment from the “Seinfeld” show—Jerry’s puffy pirate shirt and his suede jacket or his encounters with the close-talker and the woman with man hands; the impermeable maitre d’ at the Chinese restaurant; Elaine’s spastic dancing or deciding whether a potential beau was worth the investment of a precious, discontinued birth-control sponge; Kramer’s at-home talk-show set; George’s mortifying “shrinkage” after a dip in a chilly pool or the time he quit his job with a tirade, then showed up for work the next day as if nothing had happened. -

Jack Black Emm Gryner Hurricane Aftermath Smokeless On

Jack Black Emm Gryner Hurricane Aftermath Smokeless on Dal Dalhousie Student Union TH'")OME - · The nomina ·ons for the DSU Presidential By election will open on Friday, October lOth and will close on Friday, October 1~. If you have any questions please contact Ian Shelton, DSU Chief Returning Officer at [email protected]. Editorial REPO KEMPT Editor-ln..Chiei Three hours. amidst the aftermath of the following days. Despite these tragedies, the hurricane brought out many of That is all the time it took for Hurricane Juan to the best qualities of this city. Strangers who had been immobilize and ravage an entire city, and leave thou neighbours for years finally met at backyard barbeques Editorial 3 sands of citizens without power for almost a week. I where citizens gathered in packs to cook the remains never thought I'd get to write another 'back to school' of their rapidly defrosting freezer meats. Spontaneous News 4 editorial. but thanks to Mother Nature, here it is: clean-up crews helped elderly citizens clear their yards and driveways. Store owners doled out free ice cream Opinions 8 Classes have finally returned to full swing and the rather than watch it melt. It was an Irritating week of power has been restored to our fair campus. After a cold showers and long waits for coffee, and we may Arts IO week of rest and candle-lit meals and conversations, I have lost quite a few trees and telephone poles, but we hope that you are all ready to roll. If not, don't worry, really came together as a city and survived. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P.