John Cage's "The Wonderful Widow of Eighteen Springs"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Futurist Moment : Avant-Garde, Avant Guerre, and the Language of Rupture

MARJORIE PERLOFF Avant-Garde, Avant Guerre, and the Language of Rupture THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS CHICAGO AND LONDON FUTURIST Marjorie Perloff is professor of English and comparative literature at Stanford University. She is the author of many articles and books, including The Dance of the Intellect: Studies in the Poetry of the Pound Tradition and The Poetics of Indeterminacy: Rimbaud to Cage. Published with the assistance of the J. Paul Getty Trust Permission to quote from the following sources is gratefully acknowledged: Ezra Pound, Personae. Copyright 1926 by Ezra Pound. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Ezra Pound, Collected Early Poems. Copyright 1976 by the Trustees of the Ezra Pound Literary Property Trust. All rights reserved. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Ezra Pound, The Cantos of Ezra Pound. Copyright 1934, 1948, 1956 by Ezra Pound. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Blaise Cendrars, Selected Writings. Copyright 1962, 1966 by Walter Albert. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 1986 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 1986 Printed in the United States of America 95 94 93 92 91 90 89 88 87 86 54321 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Perloff, Marjorie. The futurist moment. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Futurism. 2. Arts, Modern—20th century. I. Title. NX600.F8P46 1986 700'. 94 86-3147 ISBN 0-226-65731-0 For DAVID ANTIN CONTENTS List of Illustrations ix Abbreviations xiii Preface xvii 1. -

As I Exemplify: an Examination of the Musical-Literary Relationship in the Work of John Cage LYNLEY EDMEADES

As I Exemplify: An Examination of the Musical-Literary Relationship in the Work of John Cage LYNLEY EDMEADES A thesis submitted for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS at the University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand June 2013 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the ways in which John Cage negotiates the space between musical and literary compositions. It identifies and analyses the various tensions that a transposition between music and text engenders in Cage’s work, from his turn to language in the verbal score for 4’ 33’’ (1952/1961), his use of performed and performative language in the literary text “Lecture on Nothing” (1949/1959), and his attempt to “musicate” language in the later text “Empty Words” (1974–75). The thesis demonstrates the importance of the tensions that occur between music and literature in Cage’s paradoxical attempts to make works of “silence,” “nothing,” and “empty words,” and through an examination of these tensions, I argue that our experience of Cage’s work is varied and manifold. Through close attention to several performances of Cage’s work— by both himself and others—I elucidate how he mines language for its sonic possibilities, pushing it to the edge of semantic meaning, and how he turns from systems of representation in language to systems of exemplification. By attending to the structures of expectation generated by both music and literature, and how these inform our interpretation of Cage’s work, I argue for a new approach to Cage’s work that draws on contemporary affect theory. Attending to the affective dynamics and affective engagements generated by Cage’s work allows for an examination of the importance of pre-semiotic, pre-structural responses to his work and his performances. -

What Cant Be Coded Can Be Decorded Reading Writing Performing Finnegans Wake

ORBIT - Online Repository of Birkbeck Institutional Theses Enabling Open Access to Birkbecks Research Degree output What cant be coded can be decorded Reading Writing Performing Finnegans Wake http://bbktheses.da.ulcc.ac.uk/198/ Version: Public Version Citation: Evans, Oliver Rory Thomas (2016) What cant be coded can be decorded Reading Writing Performing Finnegans Wake. PhD thesis, Birkbeck, University of London. c 2016 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copyright law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit guide Contact: email “What can’t be coded can be decorded” Reading Writing Performing Finnegans Wake Oliver Rory Thomas Evans Phd Thesis School of Arts, Birkbeck College, University of London (2016) 2 3 This thesis examines the ways in which performances of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake (1939) navigate the boundary between reading and writing. I consider the extent to which performances enact alternative readings of Finnegans Wake, challenging notions of competence and understanding; and by viewing performance as a form of writing I ask whether Joyce’s composition process can be remembered by its recomposition into new performances. These perspectives raise questions about authority and archivisation, and I argue that performances of Finnegans Wake challenge hierarchical and institutional forms of interpretation. By appropriating Joyce’s text through different methodologies of reading and writing I argue that these performances come into contact with a community of ghosts and traces which haunt its composition. In chapter one I argue that performance played an important role in the composition and early critical reception of Finnegans Wake and conduct an overview of various performances which challenge the notion of a ‘Joycean competence’ or encounter the text through radical recompositions of its material. -

Digital Adaptions of the Scores for Cage Variations I, II and III

Edith Cowan University Research Online ECU Publications 2012 1-1-2012 Digital adaptions of the scores for Cage Variations I, II and III Lindsay Vickery Catherine Hope Edith Cowan University Stuart James Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ecuworks2012 Part of the Music Commons Vickery, L. R., Hope, C. A., & James, S. G. (2012). Digital adaptions of the scores for Cage Variations I, II and III. Proceedings of International Computer Music Conference. (pp. 426-432). Ljubljana. International Computer Music Association. Available here This Conference Proceeding is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ecuworks2012/165 NON-COCHLEAR SOUND _ I[M[2012 LJUBLJANA _9.-14. SEP'l'EMBER Digital adaptions of the scores for Cage Variations I, II and III Lindsay Vickery, Cat Hope, and Stuart James Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts, Edith Cowan University ABSTRACT Over the ten years from 1958 to 1967, Cage revisited to the Variations series as a means of expanding his Western Australian new music ensemble Decibel have investigation not only of nonlinear interaction with the devised a software-based tool for creating realisations score but also of instrumentation, sonic materials, the of the score for John Cage's Variations I and II. In these performance space and the environment The works works Cage had used multiple transparent plastic sheets chart an evolution from the "personal" sound-world of with various forms of graphical notation, that were the performer and the score, to a vision potentially capable of independent positioning in respect to one embracing the totality of sound on a global scale. -

Introduction to the Modern Calculus of Variations

MA4G6 Lecture Notes Introduction to the Modern Calculus of Variations Filip Rindler Spring Term 2015 Filip Rindler Mathematics Institute University of Warwick Coventry CV4 7AL United Kingdom [email protected] http://www.warwick.ac.uk/filiprindler Copyright ©2015 Filip Rindler. Version 1.1. Preface These lecture notes, written for the MA4G6 Calculus of Variations course at the University of Warwick, intend to give a modern introduction to the Calculus of Variations. I have tried to cover different aspects of the field and to explain how they fit into the “big picture”. This is not an encyclopedic work; many important results are omitted and sometimes I only present a special case of a more general theorem. I have, however, tried to strike a balance between a pure introduction and a text that can be used for later revision of forgotten material. The presentation is based around a few principles: • The presentation is quite “modern” in that I use several techniques which are perhaps not usually found in an introductory text or that have only recently been developed. • For most results, I try to use “reasonable” assumptions, not necessarily minimal ones. • When presented with a choice of how to prove a result, I have usually preferred the (in my opinion) most conceptually clear approach over more “elementary” ones. For example, I use Young measures in many instances, even though this comes at the expense of a higher initial burden of abstract theory. • Wherever possible, I first present an abstract result for general functionals defined on Banach spaces to illustrate the general structure of a certain result. -

4' 33'': John Cage's Utopia of Music

STUDIA HUMANISTYCZNE AGH Tom 15/2 • 2016 http://dx.doi.org/10.7494/human.2016.15.2.17 Michał Palmowski* Jagiellonian University in Krakow 4’ 33’’: JOHN CAGE’S UTOPIA OF MUSIC The present article examines the connection between Cage’s politics and aesthetics, demonstrating how his formal experiments are informed by his political and social views. In 4’33’’, which is probably the best il- lustration of Cage’s radical aesthetics, Cage wanted his listeners to appreciate the beauty of accidental noises, which, as he claims elsewhere, “had been dis-criminated against” (Cage 1961d: 109). His egalitarian stance is also refl ected in his views on the function of the listener. He wants to empower his listeners, thus blurring the distinction between the performer and the audience. In 4’33’’ the composer forbidding the performer to impose any sounds on the audience gives the audience the freedom to rediscover the natural music of the world. I am arguing that in his experiments Cage was motivated not by the desire for formal novelty but by the utopian desire to make the world a better place to live. He described his music as “an affi rmation of life – not an at- tempt to bring order out of chaos nor to suggest improvements in creation, but simply a way of waking up to the very life we’re living, which is so excellent once one gets one’s mind and desires out of its way and lets it act of its own accord” (Cage 1961b: 12). Keywords: John Cage, utopia, poethics, silence, noise The present article is a discussion of the ideas informing the radical aesthetics of John Cage’s musical compositions. -

John Cage's Entanglement with the Ideas Of

JOHN CAGE’S ENTANGLEMENT WITH THE IDEAS OF COOMARASWAMY Edward James Crooks PhD University of York Music July 2011 John Cage’s Entanglement with the Ideas of Coomaraswamy by Edward Crooks Abstract The American composer John Cage was famous for the expansiveness of his thought. In particular, his borrowings from ‘Oriental philosophy’ have directed the critical and popular reception of his works. But what is the reality of such claims? In the twenty years since his death, Cage scholars have started to discover the significant gap between Cage’s presentation of theories he claimed he borrowed from India, China, and Japan, and the presentation of the same theories in the sources he referenced. The present study delves into the circumstances and contexts of Cage’s Asian influences, specifically as related to Cage’s borrowings from the British-Ceylonese art historian and metaphysician Ananda K. Coomaraswamy. In addition, Cage’s friendship with the Jungian mythologist Joseph Campbell is detailed, as are Cage’s borrowings from the theories of Jung. Particular attention is paid to the conservative ideology integral to the theories of all three thinkers. After a new analysis of the life and work of Coomaraswamy, the investigation focuses on the metaphysics of Coomaraswamy’s philosophy of art. The phrase ‘art is the imitation of nature in her manner of operation’ opens the doors to a wide- ranging exploration of the mimesis of intelligible and sensible forms. Comparing Coomaraswamy’s ‘Traditional’ idealism to Cage’s radical epistemological realism demonstrates the extent of the lack of congruity between the two thinkers. In a second chapter on Coomaraswamy, the extent of the differences between Cage and Coomaraswamy are revealed through investigating their differing approaches to rasa , the Renaissance, tradition, ‘art and life’, and museums. -

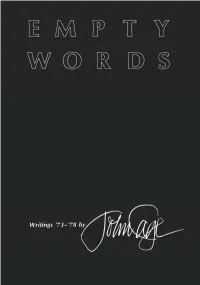

EMPTY WORDS Other

EMPTY WORDS Other Wesley an University Press books by John Cage Silence: Lectures and Writings A Year from Monday: New Lectures and Writings M: Writings '67-72 X: Writings 79-'82 MUSICAGE: CAGE MUSES on Words *Art*Music l-VI Anarchy p Writings 73-78 bv WESLEYAN UNIVERSITY PRESS Middletown, Connecticut Published by Wesleyan University Press Middletown, CT 06459 Copyright © 1973,1974,1975,1976,1977,1978,1979 by John Cage All rights reserved First paperback edition 1981 Printed in the United States of America 5 Most of the material in this volume has previously appeared elsewhere. "Preface to: 'Lecture on the Weather*" was published and copyright © 1976 by Henmar Press, Inc., 373 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10016. Reprint pernr~sion granted by the publisher. An earlier version of "How the Piano Came to be Prepared" was originally the Introduction to The Well-Prepared Piano, copyright © 1973 by Richard Bunger. Reprinted by permission of the author. Revised version copyright © 1979 by John Cage. "Empty Words" Part I copyright © 1974 by John Cage. Originally appeared in Active Anthology. Part II copyright © 1974 by John Cage. Originally appeared in Interstate 2. Part III copyright © 1975 by John Cage. Originally appeared in Big Deal Part IV copyright © 1975 by John Cage. Originally appeared in WCH WAY. "Series re Morris Graves" copyright © 1974 by John Cage. See headnote for other information. "Where are We Eating? and What are We Eating? (Thirty-eight Variations on a Theme by Alison Knowles)" from Merce Cunningham, edited and with photographs and an introduction by James Klosty. -

A Performer's Guide to the Prepared Piano of John Cage

A Performer’s Guide to the Prepared Piano of John Cage: The 1930s to 1950s. A document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Keyboard Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music By Sejeong Jeong B.M., Sookmyung Women’s University, 2011 M.M., Illinois State University, 2014 ________________________________ Committee Chair : Jeongwon Joe, Ph. D. ________________________________ Reader : Awadagin K.A. Pratt ________________________________ Reader : Christopher Segall, Ph. D. ABSTRACT John Cage is one of the most prominent American avant-garde composers of the twentieth century. As the first true pioneer of the “prepared piano,” Cage’s works challenge pianists with unconventional performance practices. In addition, his extended compositional techniques, such as chance operation and graphic notation, can be demanding for performers. The purpose of this study is to provide a performer’s guide for four prepared piano works from different points in the composer’s career: Bacchanale (1938), The Perilous Night (1944), 34'46.776" and 31'57.9864" For a Pianist (1954). This document will detail the concept of the prepared piano as defined by Cage and suggest an approach to these prepared piano works from the perspective of a performer. This document will examine Cage’s musical and philosophical influences from the 1930s to 1950s and identify the relationship between his own musical philosophy and prepared piano works. The study will also cover challenges and performance issues of prepared piano and will provide suggestions and solutions through performance interpretations. -

Extremal Overlap-Free and Extremal Β-Free Binary Words Arxiv

Extremal overlap-free and extremal β-free binary words Lucas Mol and Narad Rampersad∗ Department of Mathematics and Statistics, The University of Winnipeg [email protected], [email protected] Jeffrey Shallity School of Computer Science, University of Waterloo [email protected] Abstract An overlap-free (or β-free) word w over a fixed alphabet Σ is extremal if every word obtained from w by inserting a single letter from Σ at any position contains an overlap (or a factor of exponent at least β, respectively). We find all lengths which admit an extremal overlap- free binary word. For every extended real number β such that 2+ ≤ β ≤ 8=3, we show that there are arbitrarily long extremal β-free binary words. MSC 2010: 68R15 Keywords: overlap-free word; extremal overlap-free word; β-free word; extremal β-free word arXiv:2006.10152v1 [math.CO] 17 Jun 2020 1 Introduction Throughout, we use standard definitions and notations from combinatorics on words (see [11]). For every integer n ≥ 2, we let Σn denote the alphabet ∗The work of Narad Rampersad is supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), [funding reference number 2019-04111]. yThe work of Jeffrey Shallit is supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), [funding reference number 2018-04118]. 1 f0; 1;:::; n-1g. The word u is a factor of the word w if we can write w = xuy for some (possibly empty) words x; y.A square is a word of the form xx, where x is nonempty. -

Nicholas Isherwood Performs John Cage

aria nicholas isherwood performs john cage nicholas isherwood BIS-2149 BIS-2149_f-b.indd 1 2014-12-03 11:19 CAGE, John (1912–92) 1 Aria (1958) with Fontana Mix (1958) 5'07 Realization of Fontana Mix by Gianluca Verlingieri (2006–09) Aria is here performed together with a new version of Fontana Mix, a multichannel tape by the Italian composer Gianluca Verlingieri, realized between 2006 and 2009 for the 50th anniversary of the original tape (1958–2008), and composed according to Cage’s indications published by Edition Peters in 1960. Verlingieri’s version, already widely performed as tape-alone piece or together with Cage’s Aria or Solo for trombone, has been revised specifically for the purpose of the present recording. 2 A Chant with Claps (?1942–43) 1'07 2 3 Sonnekus (1985) 3'42 4 Eight Whiskus (1984) 3'50 Three songs for voice and closed piano 5 A Flower (1950) 2'58 6 The Wonderful Widow of Eighteen Springs (1942) 3'02 7 Nowth Upon Nacht (1984) 0'59 8 Experiences No. 2 (1945–48) 2'38 9 Ryoanji – version for voice and percussion (1983–85) 19'36 TT: 44'53 Nicholas Isherwood bass baritone All works published by C.F. Peters Corporation, New York; an Edition Peters Group company ere comes Cage – under his left arm, a paper bag full of recycled chance operations – in his right hand, a copy of The Book of Bosons – the new- Hfound perhaps key to matter. On his way home he stops off at his favourite natural food store and buys some dried bulgur to make a refreshing supper of tabouleh. -

The Cage Dialogues: a Memoir William Anastasi

Anastasi William Dialogues Cage The Foundation Slought Memoir / Conceptual Art / Contemporary Music US/CAN $25.00 The Cage Dialogues: A Memoir William Anastasi Cover: William Anastasi, Portrait of John Cage, pencil on paper, 1986 The Cage Dialogues: A Memoir William Anastasi Edited by Aaron Levy Philadelphia: Slought Books Contemporary Artist Series, No. 6 © 2011 William Anastasi, John Cage, Slought Foundation All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book, or parts thereof, in any form, without written permission from either the author or Slought Books, a division of Slought Foundation. No part may be stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in reviews for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast. This publication was made possible in part through the generous financial support of the Evermore Foundation and the Society of Friends of the Slought Foundation. Printed in Canada on acid-free paper by Coach House Books, Ltd. Set in 11pt Arial Narrow. For more information, http://slought.org/books/ “The idiots! They were making fun of you...” John Cage Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Anastasi, William, 1933- The Cage dialogues : a memoir / by William Anastasi ; edited by Aaron Levy. p. cm. -- (Contemporary artist series ; no. 6) ISBN 978-1-936994-01-4 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Cage, John. 2. Composers--United States--Biography. 3. Artists--United States-- Biography. I. Levy, Aaron, 1977- II. Title. ML410.C24A84 2011 780.92--dc22 [B] 2011016945 Caged Chance 1 William Anastasi You Are 79 John Cage and William Anastasi Selected Works, 1950-2007 101 John Cage and William Anastasi John Cage, R/1/2 [80] (pencil on paper), 1985 Caged Chance William Anastasi Now I go alone, my disciples, You, too, go now alone..