DPEP Gender Studies Madhya Pradesh D8235.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Forest of Madhya Pradesh

Build Your Own Success Story! FOREST OF MADHYA PRADESH As per the report (ISFR) MP has the largest forest cover in the country followed by Arunachal Pradesh and Chhattisgarh. Forest Cover (Area-wise): Madhya Pradesh> Arunachal Pradesh> Chhattisgarh> Odisha> Maharashtra. Forest Cover (Percentage): Mizoram (85.4%)> Arunachal Pradesh (79.63%)> Meghalaya (76.33%) According to India State of Forest Report the recorded forest area of the state is 94,689 sq. km which is 30.72% of its geographical area. According to Indian state of forest Report (ISFR – 2019) the total forest cover in M.P. increased to 77,482.49 sq km which is 25.14% of the states geographical area. The forest area in MP is increased by 68.49 sq km. The first forest policy of Madhya Pradesh was made in 1952 and the second forest policy was made in 2005. Madhya Pradesh has a total of 925 forest villages of which 98 forest villages are deserted or located in national part and sanctuaries. MP is the first state to nationalise 100% of the forests. Among the districts, Balaghat has the densest forest cover, with 53.44 per cent of its area covered by forests. Ujjain (0.59 per cent) has the least forest cover among the districts In terms of forest canopy density classes: Very dense forest covers an area of 6676 sq km (2.17%) of the geograhical area. Moderately dense forest covers an area of 34, 341 sqkm (11.14% of geograhical area). Open forest covers an area of 36, 465 sq km (11.83% of geographical area) Madhya Pradesh has 0.06 sq km. -

Directory Establishment

DIRECTORY ESTABLISHMENT SECTOR :RURAL STATE : MADHYA PRADESH DISTRICT : Anuppur Year of start of Employment Sl No Name of Establishment Address / Telephone / Fax / E-mail Operation Class (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) NIC 2004 : 0501-Fishing 1 HARFEEN H.NO.23 VILLAGE BAWDHWATOLA THASIL ANUPPUR DIST. ANUPPUR PIN CODE: NA , STD CODE: 2000 10 - 50 NA , TEL NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. NIC 2004 : 1010-Mining and agglomeration of hard coal 2 PRINCIPAL GOVERNMENT HIGH SCHOOL GIRARI TEHSIL PUSHPRAJGARH DISTRICT ANUPPUR PIN CODE: 2000 101 - 500 484881, STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. 3 COLE MINES VILLAGE BARTARAI TAHSIL KOTMA DIST. ANUPPUR PIN CODE: NA , STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: 1999 > 500 NA , FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. NIC 2004 : 1531-Manufacture of grain mill products 4 AMA TOLA SWA SAYATHA SAMOH VILLAGE UFARIKHURD TASHIL PUSHPARAJGARH DISTRICT ANUPPUR PIN CODE: 484881, STD 2002 10 - 50 CODE: NA , TEL NO: 1, FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. NIC 2004 : 1544-Manufacture of macaroni, noodles, couscous and similar farinaceous products 5 AMARBATI SWA SAYATHA SAMOH VILLAGE BENDI TAHSIL PUSHPRAJGARH DISTRTCT ANUPPUR PIN CODE: 484881, STD CODE: 2001 10 - 50 NA , TEL NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. 6 NARMADA SWA SAYATHA SAMOH H.NO.31, KARRA TOLA TAHSIL ANUPPUR DISTRICT ANUPPUR PIN CODE: NA , STD CODE: NA , 2002 10 - 50 TEL NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. 7 BACHHE LAL SINGH VILLAGE DHANPURI PUSAHPRAJGARH DIST. ANUPPUR PIN CODE: NA , STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: 2002 10 - 50 NA , FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. -

State Agriculture Infrastructure Development Plan 2012-17, Madhya Pradesh

State Agriculture Infrastructure Development Plan (SAIDP) Under Rashtriya Krishi Vikas Yojana Twelfth Five Year Plan Period (Year 2012 to 2017) Soil Testing Lab Agriculture Extension & Training Center Submitted to: Government of India Ministry of Agriculture, Cooperation and Farmer Welfare New Delhi Submitted by Government of Madhya Pradesh Department of Farmer Welfare & Agriculture Development, State Agriculture Infrastructure Development Plan 2012-17, Madhya Pradesh INDEX CHAPTER – 1 INTRODUCTION & METHODOLOGY 4 1.1 Major Areas of Focus 11 1.2 Objectives of SAIDP 11 1.3 Approach and Methodology for the District and State Plan 12 1.4 Steps Followed in Developing District Plans 12 CHAPTER – II RESOURCE BASE AND CURRENT STATUS OF THE ECONOMY 14 2.1 Zonal Classifications 14 2.2 Geomorphologic Zones 14 2.3 Land Use Pattern in Madhya Pradesh State 22 2.4 Operational Holdings 28 2.5 Irrigation 31 2.6 Sources of Irrigation 31 2.7 Agriculture 34 2.8 Horticulture 46 2.9 Agricultural Engineering 49 2.10 Animal Husbandry and Dairy 50 2.11 Fisheries 53 CHAPTER III STRENGTH, WEAKNESS, OPPORTUNITIES AND CHALLENGES 59 SWOC Analysis 3.1 Agriculture Sector 59 3.2 Horticulture Sector 62 3.3 Agriculture Engineering 65 3.4 Animal Husbandry Sector 65 3.5 Fisheries Sector 66 CHAPTER IV MADHYA PRADESH: VISION 2020 68 4.1 Indian Agriculture at a Glance 68 4.2 Emerging Trends 70 4.3 Main Issues 71 4.4 Vision 71 4.5 Challenges, Policies and Strategies 72 GoMP, Department of Farmer Welfare & Agriculture Development, Page 2 State Agriculture Infrastructure Development -

Ethno-Medicines Used by Tribals of Central India

International Journal of Applied Research 2017; 3(1): 595-598 ISSN Print: 2394-7500 ISSN Online: 2394-5869 Ethno-medicines used by tribals of central India: Impact Factor: 5.2 IJAR 2017; 3(1): 595-598 A review www.allresearchjournal.com Received: 22-11-2016 Accepted: 27-12-2016 Javed Iqbal, Aijaz Ahmad Ganaie and Shoket Ali Javed Iqbal Department of Post-Graduate Abstract Studies and Research in Forest and forest products have historically played a significant role in the economy as well as culture Biological Sciences, Rani and religious in this region since ancient time. Forest has played an important part in history of Durgavati University, civilization. They have affected the distribution of mankind over the earth surface and have influenced Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh, the religious life of primitive people. In India, the Indigenous people are predominantly composed of India the large and diverse tribal population scattered across several states. Tribal people and medical Aijaz Ahmad Ganaie practices are co-related with forest ecology. There were 46 recognized scheduled tribes and three of Department of Post-Graduate them have been identified as “Special Primitive Tribal Groups” in the State. The main tribal groups in Studies and Research in Madhya Pradesh are Gond, Bhil, Baiga, Korku, Bhariya, Halba, Kaul, Mariya, and Sahariya. Dhar, Biological Sciences, Rani Jhabua and Mandla districts have more than 50 percent tribal population. In Khargone, Chhindwara, Durgavati University, Seoni, Sidhi and Shahdol districts 30 to 50 percent population is of tribes. Maximum population is that Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh, of Gond tribes. Tribal communities in this region like Gond, Bhil, Baiga, Korku, Bhariya, Halba, Kaul, India Mariya, sahariya. -

District Survey Report District: Vidisha Madhya Pradesh

DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT DISTRICT: VIDISHA MADHYA PRADESH AS PER NOTIFICATION OF MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT, FOREST AND CLIMATE CHANGE. GOVT. OF INDIA, NEW DELHI, NO. S.O. 141(E), THE 15TH JANUARY, 2016 DIRECTORATE OF GEOLOGY AND MINING, M.P. MINERAL RESOURCE DEPARTMENT, GOVT OF M. P. BHOPAL [email protected] 2016 CONTENT S.N. Subject 1 Introduction 2 General 3 Geomorphology 4 Geology 5 Mineral Resources 6 Overview of Mining activity in the District 7 Details of Royalty or revenue received in last three years 8 Details of production of sand or bajari or minor mineral in the last three years 9 The list of Mining Lease in the District with location, area and period of validity 10 Drainage 11 Process of deposition of sediment in the river of the district 12 General profile of district 13 Rainfall 14 Land utilization patter in the district 15 Mineral Potential 16 Geological And Mineral Map 17 Map Index 18 Geomorphological Map 19 Geohydrological Map 20 Geotechnicaland Natural Hazards Map 21 Land use Map 1.INTRODUCTION As per the order issued by the Mineral Resources department Govt of M P the District Survey Report is to be prepared for the fulfilment of the notification of the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate change Govt of India dated Jan. 15th 2016. “MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT, FOREST AND CLIMATE CHANGE NOTIFICATION New Delhi, the 15th January, 2016 S.O. 141(E).—Whereas in exercise of the powers conferred by sub-section (1) and clause (v) of sub-section (2) of section 3 of the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986 (29 of 1986), read with -

Relocation of Staff Nurse

Summary of Staff Nurses Sanctioned post in M.P. Post Sanctioned in Gazette 2011 7763 Post Sanctioned after July 2011 377 Total 8140 Institution wise Sanctioned posts Civil Hospital 1030 District Hospital 4730 CHC 1733 PHC 647 Grand Total 8140 Location Division District DDO Code Beds Facility Center Name facility Type No. Of Staff Code Nurse BHOPAL Betul 660101 0301704004 300 Betul-District Hospital CEmONC DH 100 BHOPAL Betul 660801 0301707001 30 Betul-CHC, Aamla Non CEMoNC CHC 5 BHOPAL Betul 660802 0301707001 30 Betul-CHC, Aathner Non CEMoNC CHC 5 BHOPAL Betul 660803 0301707001 30 Betul-CHC, Bhainsdehi CEMoNC CHC 6 BHOPAL Betul 660804 0301707001 30 Betul-CHC, Bhimpur Non CEMoNC CHC 5 BHOPAL Betul 660805 0301707001 30 Betul-CHC, Chicholi Non CEMoNC CHC 5 BHOPAL Betul 660806 0301707001 30 Betul-CHC, Ghodadongri CEMoNC CHC 6 BHOPAL Betul 660807 0301707001 30 Betul-CHC, Multai Non CEMoNC CHC 5 BHOPAL Betul 660808 0301707001 30 Betul-CHC, Prabhatpattan Non CEMoNC CHC 5 BHOPAL Betul 660809 0301707001 30 Betul-CHC, Sehra Non CEMoNC CHC 5 BHOPAL Betul 660810 0301707001 30 Betul-CHC, Shapur Non CEMoNC CHC 5 Bhopal Betul Aamdhana PHC 1 Bhopal Betul Barhavi PHC 1 Bhopal Betul Betula Bazar PHC 1 Bhopal Betul Bhora PHC 1 Bhopal Betul Bishnupur PHC 1 Bhopal Betul Bordehi PHC 1 Bhopal Betul Chirapatla PHC 1 Bhopal Betul Chunalohma PHC 1 Bhopal Betul Damjipura PHC 1 Bhopal Betul Dunawa PHC 1 Bhopal Betul Hidli PHC 1 Bhopal Betul Hirapur PHC 1 Bhopal Betul Jhallar PHC 1 29Of 1 Bhopal Betul Khamla PHC 1 Bhopal Betul Masod PHC 1 Bhopal Betul Mohata PHC 1 Bhopal Betul Morkha PHC 1 Bhopal Betul Pathakheda PHC 1 Bhopal Betul Ranipur PHC 1 BHOPAL Bhopal 630202 0521707006 20 Bhopal-Civil Hospital, K. -

District Survey Report

DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT OF ASHOKNAGAR DISTRICT PREPARED BY PRASHANT KUMAR TIWARI MINING OFFICER MINING OFFICE ASHOKNAGAR (M.P.) Phone No. – (9685579251) E-Mail – [email protected] CHAPTER – 1 INTRODUCTION According to Para 7(iii) Parishist 10 of Notification dated 15 january 2016 of Environment, Forest and Climate Change Ministry Government of India. Mineral wise District Survey report will be prepared in every district for Sand mining or River bed mining and other small minerals mining. The main purpose to prepare the district survey report is to identify the land increase or deposional areas and its infrastructure, Structure and installation distance from where the mining is prohibited and re calculation of annual replenishment and time required for replenishment after mining. The district survey report will be based on the application for evaluation of project. This report is prepared for mineral of District Ashoknagar. District Ashoknagar comes under Administration divisions of Gwalior (M.P.) The district is bounded by Guna, Shivpuri, Lalitpur (U.P.), Sagar & Vidisha. The Ashoknagar District is located in the Northern part of Madhya Pradesh State and is covered in Survey of India Degree Sheet Nos., 63A, 63C, 63D, & 63H between Latitude 24°57’-83°49’ and Longitude 77°73’ - 22°91” District Ashoknagar covers an area of 4673.94 square kilometers. Ashoknagar is the district headquarter and Chanderi, Isagarh, Mungaoli, Shadora, Naisaray, Piprai are some of the Tehsil Place. The Kota- Bina section of the west central railway through the district. All important places within the district are well connected by a network of state highways and all weather roads, The Betwa, Sindh & Aur rivers and its tributaries drain whole area of the district. -

Executive Summary Es.�1

Consultancy services for feasibility study for Shivpuri to Executive Summary Dewas Section of NH-3 (Package-II) Highway Project in the State of Madhya Pradesh EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ES. 1 . Introduction The National Highways Authority of India (NHAI) has been entrusted the task of development of Phase IV (NHDP) Projects. National Highway No. 3 commonly referred to as the AB road, is a major Indian National Highway that runs through Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra states in India. The highway is start at Agra in Uttar Pradesh and end at Mumbai. It travels through Dhaulpur (Rajasthan), Gwalior, Shivpuri, Guna, Biaora, Maksi, Dewas and Indore (Madhya Pradesh) and Dhule, Nashik, and Thane (Maharashtra). Total length of NH-3 is approx 1161 Km. Study of the proposed construction activities is carried out to establish the baseline environmental aspects of the project corridor and to analyze all the expected impacts, required avoidance and the possible cost effective mitigation measures. These mitigation measures need to be stream lined with the engineering design and social impact for effective implementation. ES.2 PROJECT DESCRIPTION The Package-II of Shivpuri-Dewas section of National Highway 3 has selected as one of highway to be developed under NHDP IV, this project is only for widening & strengthening of existing 2 lane road to 4/6 lane & improvement of its geometry. The total length of the project is 332.600 Km (including Guna bypass) from Km 236.00 (Chainage 000+000) to Km 566.450 (Chainage 332.600 (Fig. ES.1 ). The project road passing through the Six districts with 290 Nos villages viz., Shivpuri, Guna, Rajgarh, Shajapur, Ujjain and Dewas (Shivpuri District – 34 nos., Guna District – 87 Nos, Rajgarh District – 110 Nos, Shajapur District – 29 Nos, Ujjain District – 11 Nos and Dewas District – 15 Nos.) in the state of Madhya Pradesh. -

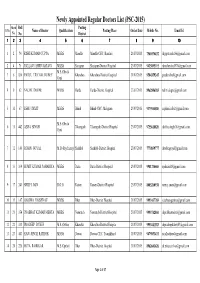

Newly Appointed Regular Doctors List (PSC-2015) Merit Roll Posting S.No

Newly Appointed Regular Doctors List (PSC-2015) Merit Roll Posting S.No. Name of Doctor Qualification Posting Place Order Date Mobile No. Email Id No. No. District 111222 333 444 555 666 777 888 999 101010 1 2 74 RISHI KUMAR GUPTA MBBS Mandla Mandla-CHC, Bamhni 23/07/2015 7566936432 [email protected] 2 4 76 PALLAVI SHRIVASTAVA MBBS Shajapur Shajapur-District Hospital 23/07/2015 9425895115 [email protected] M.S.(Obs & 3 6 856 PARUL TRICHAL DUBEY Khandwa Khandwa-District Hospital 31/07/2015 9584359245 [email protected] Gyn) 4 9 62 NALINI DOGNE MBBS Harda Harda-District Hospital 23/07/2015 8962806383 [email protected] 5 10 67 ESHU DIXIT MBBS Bhind Bhind-CHC, Mehgaon 23/07/2015 9179164880 [email protected] M.S.(Obs & 6 11 442 ABHA SINGH Tikamgarh Tikamgarh-District Hospital 23/07/2015 9755618820 [email protected] Gyn) 7 12 145 ROBIN GOYAL M.D.(Psychiatry) Shahdol Shahdol-District Hospital 23/07/2015 7770839777 [email protected] 8 16 369 SUMIT KUMAR PAHARIYA MBBS Datia Datia-District Hospital 23/07/2015 9981214660 [email protected] 9 17 241 SHILPI JAIN D.G.O. Raisen Raisen-District Hospital 23/07/2015 8085260938 [email protected] 10 19 147 GARIMA VAISHNAV MBBS Dhar Dhar-District Hospital 31/07/2015 9993437769 [email protected] 11 21 354 PRABHAT KUMAR MEHTA MBBS Neemuch Neemuch-District Hospital 23/07/2015 9993742804 [email protected] 12 22 333 PRADEEP DUBEY M.S.(Ortho) Khandwa Khandwa-District Hospital 23/07/2015 9993441383 [email protected] 13 23 443 RAJU SINGH RATHOR MBBS Dewas Dewas-CHC, Toankkhurd 31/07/2015 9479853433 [email protected] 14 24 226 EKTA RAIRIKAR M.S.(Optho) Dhar Dhar-District Hospital 31/07/2015 8962603626 [email protected] Page 1 of 47 Merit Roll Posting S.No. -

State of Agriculture in Madhya Pradesh

Study No.112 STATE OF AGRICULTURE IN MADHYA PRADESH AGRO- ECONOMIC RESEARCH CENTRE FOR MADHYA PRADESH AND CHHATTISGARH Jawaharlal Nehru Krishi Vishwa Vidyalaya, Jabalpur (M.P.) 2013 STATES OF AGRICULTURE IN MADHYA PRADESH Dr. Hari Om Sharma Dr. Deepak Rathi Mr. Ravi Singh Chouhan Mr. Shiv Charan Meena Report Submitted to The Ministry of Agriculture, Government of India, New Delhi AGRO- ECONOMIC RESEARCH CENTRE FOR MADHYA PRADESH AND CHHATTISGARH Jawaharlal Nehru Krishi Vishwa Vidyalaya, Jabalpur (M.P.) 2013 Preface Madhya Pradesh, the second largest state of the country is located in the central India, comprising 11 Agro – Climatic zones with diverse soil and climatic condition, which helps to support to cultivation of a wide range of crops with diversified cropping pattern. Madhya Pradesh stands in the top most position for producing pulses, oilseeds, garlic and coriander with highest cattle population in India. The diversified cropping pattern and the highest cattle population helped to cultivate organic farming in 40 per cent of the area under of the total agriculture land of the country, which not only helps to minimize the risk associated with rainfed agriculture but also improve the soil health and there by facilitate the sustained the inclusive growth of agricultural sector through sustainable development. The state has got Krish Karmath Award of 2012 for development and extension of newer modern technology of agriculture and honour of the best agriculture state of India in the year 2013 for highest agricultural growth (18% per annum). In spite of the above progress of agriculture in the state there are so many challenges are exist which needs to be addressed for prolong growth. -

Human Rights with New Preface 2009.Indd

Asian Centre for Human Rights is dedicated to promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the Asian region by: n providing accurate and timely information and complaints to the National Human Rights Institutions, the United Nations bodies and mechanisms as appropriate; INDIA n conducting investigation, research, campaigning and lobbying on country HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT situations or individual cases; n increasing the capacity of human rights defenders and civil society groups through relevant trainings on the use of national and international human rights procedures; n providing input into international standard setting processes on human rights; n providing legal, political and practical advice according to the needs of human rights defenders and civil society groups; and n by securing the economic, social and cultural rights through rights-based approaches to development. ASIAN CENTRE FOR HUMAN RIGHTS C-3/441-C, Janakpuri, New Delhi 110058 INDIA Phone/Fax: +91 11 25620583, 25503624 Website: www.achrweb.org Email: [email protected] ASIAN CENTRE FOR HUMAN RIGHTS INDIA HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT ASIAN CENTRE FOR HUMAN RIGHTS India Human Rights Report 2009 Edited by: Suhas Chakma, Director, Asian Centre for Human Rights Published by: Asian Centre for Human Rights C-3/441-C, Janakpuri, New Delhi 110058, INDIA Tel/Fax: +91 11 25620583, 25503624 Website: www.achrweb.org Email: [email protected] First published May 2009 ©Asian Centre for Human Rights, 2009 No part of this publication can be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the publisher. Cover photo: Voters for the 2009 general elections; Source: http://www. -

1. District Brief Profile

1. DISTRICT BRIEF PROFILE A- DISTRICT POLITICAL MAP B- KEY STATISTICS POPULATION – 2011 1241519 PROJECTED POPULATION - (Current Year) 1464992 POPULATION DENSITY 194 LITERACY RATE TOTAL 63.23% LITERACY RATE MALE 74.05% LITERACY RATE FEMALE 51.36% GROWTH RATE – TOTAL 26.97 GROWTH RATE – URBAN 30.87 GROWTH RATE – RURAL 25.71 NO. OF MUNICIPAL CORPORATION 00 NO. OF MUNICIPALITIES 05 NO. OF BLOCKS 05 NO. OF GRAM PANCHAYATS 425 NO. OF REVENUE VILLAGES 1375 TOTAL ELECTORS IN DISTRICT 815962 MALE ELECTORS 431346 FEMALE ELECTORS 384553 SEX RATIO – 2011 911 SEX RATIO - (As per final roll) EP RATIO – 2011 EP RATIO - (As per final roll) NO. OF PARLIAMENTARY CONSTITUENCIES (PC) 02 (Partially) NO. OF POLING STATION (PS) 1065 NO. OF POLLING STATION LOCATIONS 970 NO. OF ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCIES (AC) 04 NO. OF RETURNING OFFICERS (RO) 04 NO. OF AROS 12 NO. OF SECTOR OFFICERS (SO) NO. OF BLOS 1065 C- BRIEF NOTIES ON THE DISTRICT Write very briefly about the district India is a vast country and considering the size, geography and culture, conducting election has always been an arduous task. It is termed as a biggest festival of democracy, whereby, a government is elected through the people’s participation. It is indeed a tough task for the authority to conduct the free and fair polling with proper security to electors and polling personnel. Hence, it is strongly recommended to have a robust election management plan, in line with the prescribed guidelines and instructions, with the authority which deals with the each and every aspect of election preparedness. All officers are, therefore, advised to be familiarized and acquainted with each measure to be adopted at various stages of electoral processes and election management plan can be a better tool to guide the concerned officials.