Program Notes International Contemporary Ensemble

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

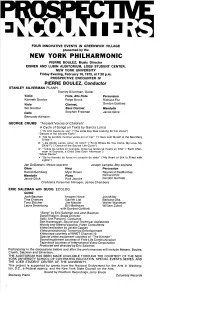

Prospective Encounters

FOUR INNOVATIVE EVENTS IN GREENWICH VILLAGE presented by the NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC PIERRE BOULEZ, Music Director EISNER AND LUBIN AUDITORIUM, LOEB STUDENT CENTER, NEW YORK UNIVERSITY Friday Evening, February 18, 1972, at 7:30 p.m. PROSPECTIVE ENCOUNTER IV PIERRE BOULEZ, Conductor STANLEY SILVERMAN PLANH Stanley Silverman, Guitar Violin Flute, Alto Flute Percussion Kenneth Gordon Paige Brook Richard Fitz Viola Clarinet, Gordon Gottlieb Sol Greitzer Bass Clarinet Mandolin Cello Stephen Freeman Jacob Glick Bernardo Altmann GEORGE CRUMB "Ancient Voices of Children" A Cycle of Songs on Texts by Garcia Lorca I "El niho busca su voz" ("The Little Boy Was Looking for his Voice") "Dances of the Ancient Earth" II "Me he perdido muchas veces por el mar" ("I Have Lost Myself in the Sea Many Times") III "6De d6nde vienes, amor, mi nino?" ("From Where Do You Come, My Love, My Child?") ("Dance of the Sacred Life-Cycle") IV "Todas ]as tardes en Granada, todas las tardes se muere un nino" ("Each After- noon in Granada, a Child Dies Each Afternoon") "Ghost Dance" V "Se ha Ilenado de luces mi coraz6n de seda" ("My Heart of Silk Is Filled with Lights") Jan DeGaetani, Mezzo-soprano Joseph Lampke, Boy soprano Oboe Harp Percussion Harold Gomberg Myor Rosen Raymond DesRoches Mandolin Piano Richard Fitz Jacob Glick PaulJacobs Gordon Gottlieb Orchestra Personnel Manager, James Chambers ERIC SALZMAN with QUOG ECOLOG QUOG Josh Bauman Imogen Howe Jon Miller Tina Chancey Garrett List Barbara Oka Tony Elitcher Jim Mandel Walter Wantman Laura Greenberg Bill Matthews -

Sfkieherd Sc~Ol Ofmusic

GUEST ARTIST RECITAL JEFFREY JACOB, Piano Thursday, September 18, 2008 8:00 p.m. Lillian H. Duncan Recital Hall sfkieherd RICE UNIVERSITY Sc~ol ofMusic PROGRAM Makrokosmos II George Crumb Twelve Fantasy-Pieces after the Zodiac (b.1929) (for amplified piano) 1. Morning Music (Genesis II) 2. The Mystic Chord 3. Rain-Death Variations 4. Twin Suns (Doppelganger aus der Ewigkeit) 5. Ghost-Nocturne: For the Druids of Stonehenge 6. Gargoyles 7. Tora I Tora I Tora I ( Cadenza Apocalittica) 8. A Prophecy of Nostradamus 9. Cosmic Wind 10. Voices from "Corona Borealis" 11. Litany of the Galactic Bells 12. Agnus Dei The reverberative acoustics of Duncan Recital Hall magnify the slightest sound made by the audience. Your care and courtesy will be appreciated. The taking ofphotographs and use ofrecording equipment are prohibited. BIOGRAPHY Described by the Warsaw Music Journal as "unquestionably one of the greatest performers of 20th-century music," and the New York Times as "an artist ofintense concentration and conviction," Jeffrey Jacob re ceived his education from the Juilliard School (Master of Music) and the Peabody Conservatory (Doctor ofMusical Arts) and counts as his prin cipal teachers Mieczyslaw Munz, Carlo Zecchi, and Leon Fleisher. Since his debut with the London Philharmonic in Royal Festival Hall, he has appeared as piano soloist with over twenty orchestras internationally including the Moscow, St. Petersburg, Seattle, Portland, Indianapolis, Charleston, Silo Paulo and Brazilian National Symphonies, and the Si lesian, Moravian , North Czech, and Royal Queenstown Philharmonics. A noted proponent ofcontemporary music, he has performed the world premieres of works written for him by George Crumb, Gunther Schuller, Vincent Persichetti, Samuel Adler, Francis Routh, and many others. -

Paper 59 2019.Pdf

1 Accademia Musicale Studio Musica International Conference on New Music Concepts and Inspired Education Proceeding Book Vol. 6 Accademia Musicale Studio Musica Michele Della Ventura Editor COPYRIGHT MATERIAL 2 Printed in Italy First edition: April 2019 ©2019 Accademia Musicale Studio Musica www.studiomusicatreviso.it Accademia Musicale Studio Musica – Treviso (Italy) ISBN: 978-88-944350-0-9 3 Preface This volume of proceedings from the conference provides an opportunity for readers to engage with a selection of refereed papers that were presented during the International Conference on New Music Concepts and Inspired Education. The reader will sample here reports of research on topics ranging from mathematical models in music to pattern recognition in music; symbolic music processing; music synthesis and transformation; learning and conceptual change; teaching strategies; e-learning and innovative learning. This book is meant to be a textbook that is suitable for courses at the advanced under- graduate and beginning master level. By mixing theory and practice, the book provides both profound technological knowledge as well as a comprehensive treatment of music processing applications. The goals of the Conference are to foster international research collaborations in the fields of Music Studies and Education as well as to provide a forum to present current research results in the forms of technical sessions, round table discussions during the conference period in a relax and enjoyable atmosphere. 36 papers from 16 countries were received. All the submissions were reviewed on the basis of their significance, novelty, technical quality, and practical impact. After careful reviews by at least three experts in the relevant areas for each paper, 12 papers from 10 countries were accepted for presentation or poster display at the conference. -

Crumb, George | Grove Music

Grove Music Online Crumb, George (Henry ) Richard Steinitz https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.A2249252 Published in print: 26 November 2013 Published online: 16 October 2013 (b Charleston, WV, Oct 24, 1929). American composer. Born to accomplished musical parents, he participated in domestic music- making from an early age, an experience that instilled a lifelong empathy with the Classical and Romantic repertory, as his Three Early Songs (1947) exemplify. He studied at Mason College (1947– 50), the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign (MM 1953), the Berlin Hochschule für Musik (Fulbright Fellow, 1955–6), where he was a student of Boris Blacher, and the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor (DMA 1959), where his teachers included Ross Lee Finney. At Ann Arbor, Crumb encountered the poetry of Federico García Lorca and listened with fellow students to Folkways recordings of world music. Debussy and Mahler were early influences, as well as Ives and the hymnody and revival songs in which Crumb was also immersed. But it was European music from Stravinsky and Ravel to the Second Viennese School and Dallapiccola that is reflected in his first significant composition, Variazioni (1959) for large orchestra, in a synthesis never doctrinaire, but sophisticated and transparent, displaying already an acute sensitivity to color. In the year of its completion, Crumb accepted a post at the University of Colorado, Boulder (1959–64) where, although employed as a piano teacher, his first mature works were composed. These include Five Pieces for Piano (1962), Night Music I (1963), which began as an instrumental composition but “came into focus” when he decided to set two poems by Lorca, and Four Nocturnes (1964). -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1970

ISM /, *w*s M •*r:;*. KUCJCW n;. ,-1. * Tanglewood 1970° Seiji Ozawa, Gunther Schuller, Artistic Directors Leonard Bernstein, Advisor FESTIVAL OF CONTEMPORARY MUSIC August 16 — August 20, 1970 Sponsored by the BERKSHIRE MUSIC CENTER In Cooperation with the FROMM MUSIC FOUNDATION PERSPECTIVES NEWOF MUSIC PERSPECTIVES OF NEW MUSIC Participants in this year's Festival are invited to subscribe to the American journal devoted to im- portant issues of contemporary music and the problems of the composer. Published for the Fromm Music Foundation by Princeton University Press. Editor: Benjamin Boretz Advisory Board: Aaron Copland, Ernst Krenek, Darius Milhaud, Walter Piston, Roger Sessions, Igor Stravinsky. Semi-annual. $6.00 a year. $15.00 three years. Foreign Postage is 25 cents additional per year. Single or back issues are $5.00. Princeton University Press Princeton, New Jersey I 5fta 'V. B , '*•. .-.-'--! HffiHHMEffl SiSsi M^lll Epppi ^EwK^^bJbe^h 1 * - ' :- HMK^HRj^EI! 9HKS&k 7?. BCJB1I MQ50 TANGLEWOOD SEIJI OZAWA, GUNTHER SCHULLER, Artistic Directors/LEONARD BERNSTEIN, Adviser THE BERKSHIRE MUSIC CENTER Joseph Silverstein, Chairman of the Faculty Harry J. Kraut, Administrator Aaron Copland, Chairman of the Faculty Emeritus Daniel R. Gustin, Assistant Administrator Leon Barzin, Head, Orchestral Activities James Whitaker, Chief Coordinator ,vvv /ss. Festival of Contemporary Music presented in cooperation with The Fromm Music Foundation Paul Fromm, President Fellowship Program Contemporary Music Activities Gunther Schuller, Head George Crumb, Charles Wuorinen, and Chou Wen-Chung, Guest Teachers Paul Zukofsky, Assistant The Berkshire Music Center is maintained for advanced study in music Sponsored by the Boston Symphony Orchestra William Steinberg, Music Director Michael Tilson Thomas, Associate Conductor Thomas D. -

Artist-In-Residence Recital Nadia Shpachenko-Gottesman, Piano Timothy Hoft, Piano

Department of MUSIC College of Fine Arts presents Artist-in-Residence Recital Nadia Shpachenko-Gottesman, piano Timothy Hoft, piano PROGRAM "Music for a New B'ak'tun and Otherworldly Resonances" Peter Yates Finger Songs for solo piano (2012) (b. 1953) Mood Swing Gambol Mysterious Dawn Brave Show All Better Adam Schoenberg Picture Etudes for solo piano (20 13) (b. 1980) Three Pierrots Mir6's World Olive Orchard Kandinsky World Premiere INTERMISSION Diego Vega Rhapsody for Two Pianos (2012) (b. 1968) World Premiere George Crumb Otherworldly Resonances (Tableaux, Book II) (b. 1929) for two amplified pianos (2005) Double Helix Celebration and Ritual Palimpsest Tuesday, March 5, 2013 7:30p.m. Dr. Arturo Rando-Grillot Recital Hall Lee and Thomas Beam Music Center University of Nevada, Las Vegas Nadia Shpachenko-Gottesman Pianist Nadia Shpachenko-Gottesman has performed extensively in solo recitals and with orchestras in major venues across North America, Europe and Asia. Described by critics as a "truly inspiring and brilliant pianist. .. spellbinding in sensitivity and mastery of technique," she recently toured Mexico with Orquesta de Baja California, performed with the Kharkov Philharmonic, the Ukrainian National Symphony and the Ukrainian National Radio Symphony Orchestras in Ukraine and the San Bernardino Symphony Orchestra in California. An enthusiastic promoter of contemporary music, she bas given world and national premieres of dozens of piano, string piano and toy piano works by composers such as Leon Kirchner, George Crumb, Henry Cowell, Elliott Carter, Iannis Xenakis, Peter Yates, Tom Flaherty, Dave Kopplin, Yury Isbchenko and others. As a distinguished chamber musician, Dr. Shpachenko bas most recently collaborated with such renowned artists as Jerome Lowenthal, Victor Rosenbaum, David Korevaar, Genevieve Lee, Martin Chalifour, Ronald Leonard, Julie Landsman, and the Biava String Quartet. -

ORCHESTRA 2001 Ann Crumb, Soprano & Patrick Mason, Baritone

Concerts from the Library of Congress 2012-2013 THE DINA KOSTON AND ROGER SHAPIRO FUND FOR NEW MUSIC ORCHESTRA 2001 Ann Crumb, soprano & Patrick Mason, baritone James Freeman, Conductor FRIDAY, May 3, 2013 8 o’clock in the EVENING Coolidge Auditorium Library of Congress, Thomas Jefferson Building THE DINA KOSTON AND ROGER SHAPIRO FUND FOR NEW MUSIC Endowed by the late composer and pianist Dina Koston (1929-2009) and her husband, prominent Washington psychiatrist Roger L. Shapiro (1927-2002), the DINA KOSTON AND ROGER SHAPIRO FUND FOR NEW MUSIC supports commissions and performances of contemporary music. In 1935 Gertrude Clarke Whittall gave the Library of Congress five Stradivari instruments and three years later built the Whittall Pavilion in which to house them. The GERTRUDE clarke whittall Foundation Thewas audio -visual equipment in the Coolidge Auditorium was funded in part by the Ira and Leonore Gershwin Fund in the Library of Congress. Please request ASL and ADA accommodations five days in advance of the concert at 202-707-6362 or [email protected]. Latecomers will be seated at a time determined by the artists for each concert. Children must be at least seven years old for admittance to the concerts. Other events are open to all ages. Please take note: UNAUTHORIZED USE OF PHOTOGRAPHIC AND SOUND RECORDING EQUIPMENT IS STRICTLY PROHIBITED. PATRONS ARE REQUESTED TO TURN OFF THEIR CELLULAR PHONES, ALARM WATCHES, OR OTHER NOISE-MAKING DEVICES THAT WOULD DISRUPT THE PERFORMANCE. Reserved tickets not claimed by five minutes before the beginning of the event will be distributed to stand-by patrons. -

Contemporary Violin Techniques: the Timbral Revolution

CONTEMPORARY VIOLIN TECHNIQUES: THE TIMBRAL REVOLUTION By Michael Vincent December 17th, 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .......................................................................................................................................................................1 From the Renaissance to the Dadaists.............................................................................................................................1 Bowing..................................................................................................................................................................................2 Sul Ponticello........................................................................................................................................................................2 Col Legno..............................................................................................................................................................................3 Col legno tratto....................................................................................................................................................................3 Subharmonics and ALF’s...................................................................................................................................................4 Percussive Techniques...................................................................................................................................................5 The Fingertips......................................................................................................................................................................5 -

Birds on a Wire 2012–13 Season Thursday 7 February 2013 341St Concert Dalton Center Recital Hall 7:30 P.M

Birds on a Wire 2012–13 Season Thursday 7 February 2013 341st Concert Dalton Center Recital Hall 7:30 p.m. WILLIS KOA, Cello JORY KING, Flute AHMED ANZALDUA, Piano SKYE HOOKHAM, Percussion ANDREW MAXBAUER, Percussion DAVID COLSON, Conductor featuring CARL RATNER, Baritone RAYMOND HARVEY, Piano VALERIA JONARD, Computer ABDERRAHMAN ANZALDUA, Computer CHRISTOPHER BIGGS, Sound Engineer/Composer ROBERT G. PATTERSON, Composer Christopher Biggs Biodiversity (2012) World Premiere b. 1979 I. 1. Monochrome 2. Sequencing 3. Action – Reaction 4. Genetic Diversity II. 5. Virus with Shoes 6. Developed Consumption (video by Barry Anderson) 7. Organisimal Diversity (video by Kevin Abbott, choreography by David Curwen and dancers*) III. 8. (re)action – (re)action (video by Richard Johnson) 9. Biofeedback 10. Ecological Diversity (video by Eric Souther) 11. Entropy (includes processed video by all collaborating video artists) intermission Robert G. Patterson American Pierrot: b. 1957 A Langston Hughes Songbook (2011) World Premiere I. Pierrot’s Passion When Sue Wears Red Midnight Dancer Love Song for Lucinda Lady’s Boogie II. Pierrot’s Estate Words Like Freedom Go Slow Visitors to the Black Belt Dream Boogie: Variation Silhouette III. Pierrot’s Heart Heart Soledad (A Cuban Portrait) Life is Fine CARL RATNER currently serves as Associate Professor of Voice at Western Michigan University. He teaches applied voice, French and German diction for singers, and vocal literature, and from 2001–10 served as Director of Opera. He is professionally active as a baritone soloist, stage director, and opera consultant. He was awarded a 2010–11 Fulbright grant to perform in recital, give lectures and master classes, direct an American chamber opera, and research Russian art songs at the St. -

A PEDAGOGICAL GUIDE to EXTENDED PIANO TECHNIQUES a Mono

A PEDAGOGICAL GUIDE TO EXTENDED PIANO TECHNIQUES ________________________________________________________________________ A Monograph Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board ________________________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS ________________________________________________________________________ by Jean-François Proulx May, 2009 © Copyright 2009 by Jean-François Proulx ii ABSTRACT A PEDAGOGICAL GUIDE TO EXTENDED PIANO TECHNIQUES Jean-François Proulx Doctor of Musical Arts Temple University, 2009 Doctoral Advisory Committee Chair: Charles Abramovic Extended piano techniques, which mainly involve playing directly on the internal components of the piano, emerged early in the twentieth century, mainly in the United States. Henry Cowell (1897-1965) explored some of these techniques in short piano pieces such as The Tides of Manaunaun (1917; clusters) The Banshee (1925; glissando, pizzicato) and Sinister Resonance (1930; mute, harmonic). Several contemporary composers followed this path. Notably, George Crumb’s (b. 1929) mature works combine conventional techniques with an unprecedented variety of extended techniques, including vocal and percussive effects. Although extended techniques are no longer a novelty, most pianists are still unfamiliar with them. Extended piano works are rarely performed or taught. This situation is regrettable considering the quality of these compositions, and the great potential of extended techniques to expand the piano’s coloristic resources. A Pedagogical Guide to Extended Piano Techniques is designed to help pianists learn this idiom and achieve fluency. Teachers may also find it useful in planning courses at the undergraduate college level. Chapters 1 and 2 provide general information such as the development and classification of unconventional techniques, and the construction of the grand piano. Chapters 3, 4 and 5 form the core of the monograph. -

Transformations Works by LEON KIRCHNER | ROGER SESSIONS | ARNOLD SCHOENBERG

Elizabeth Chang, violin Steven Beck, piano Alberto Parrini, cello Transformations WORKS BY LEON KIRCHNER | ROGER SESSIONS | ARNOLD SCHOENBERG WWW.ALBANYRECORDS.COM TROY1850 ALBANY RECORDS U.S. 915 BROADWAY, ALBANY, NY 12207 TEL: 518.436.8814 FAX: 518.436.0643 ALBANY RECORDS U.K. BOX 137, KENDAL, CUMBRIA LA8 0XD TEL: 01539 824008 © 2021 ALBANY RECORDS MADE IN THE USA DDD WARNING: COPYRIGHT SUBSISTS IN ALL RECORDINGS ISSUED UNDER THIS LABEL. THE MUSIC Leon Kirchner (1919–2009): Duo No. 2 for Violin and Piano (2002) I have often had occasion to reflect on the relationships I have formed with Although born in Brooklyn to Russian-Jewish parents, Leon Kirchner spent my own students, on the lasting influences both subtle and momentous that his formative years soaking up the Central-European musical tradition we have had on one another, and on the ways in which the particularity of from mostly Jewish émigré musicians in California—first in Los Angeles the teacher/student relationship in this art form bears fruit in our evolution where his family moved when he was nine, then in the San Francisco Bay as human beings and as musicians. Area, where he attended graduate school and later taught at UC Berkeley This selection of composers derives its rationale from my own artistic and at Mills College. In Los Angeles his connection to Central Europe heritage and the profound artistic and pedagogical influence Leon Kirchner began with the Viennese-born composer and pianist Ernest Toch at Los had on me when I was an undergraduate at Harvard. Many eminent musi- Angeles City College and continued with Toch’s friend and colleague Arnold cians of our time have attested to the legendary clarity with which Kirchner Schoenberg at UCLA. -

Encounters with the Avant-Garde: Four Case Studies in the Reception History of Contemporary Flute Works (1971 to Present)

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2016 Encounters with the Avant-Garde: Four Case Studies in the Reception History of Contemporary Flute Works (1971 to present) Amanda Cook Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Cook, Amanda, "Encounters with the Avant-Garde: Four Case Studies in the Reception History of Contemporary Flute Works (1971 to present)" (2016). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 5393. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/5393 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Encounters with the Avant-Garde: Four Case Studies in the Reception History of Contemporary Flute Works (1971 to present) Amanda Cook DMA Research Project submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements