Transformations Works by LEON KIRCHNER | ROGER SESSIONS | ARNOLD SCHOENBERG

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

100Th Season Anniversary Celebration Gala Program At

Friday Evening, May 5, 2000, at 7:30 Peoples’ Symphony Concerts 100th Season Celebration Gala This concert is dedicated with gratitude and affection to the many artists whose generosity and music-making has made PSC possible for its first 100 years ANTON WEBERN (1883-1945) Langsaner Satz for String Quartet (1905) Langsam, mit bewegtem Ausdruck HUGO WOLF (1860-1903) “Italian Serenade” in G Major for String Quartet (1892) Tokyo String Quartet Mikhail Kopelman, violin; Kikuei Ikeda, violin; Kazuhide Isomura, viola; Clive Greensmith, cello LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN (1770-1827) Trio for piano, violin and cello in B-flat Major Op. 11 (1798) Allegro con brio Adagio Allegretto con variazione The Kalichstein-Laredo-Robinson Trio Joseph Kalichstein, piano; Jamie Laredo, Violin; Sharon Robinson. cello GYORGY KURTAG (b. 1926) Officium breve in memoriam Andreae Szervánsky 1 Largo 2 Piú andante 3 Sostenuto, quasi giusto 4 Grave, moto sostenuto 5 Presto 6 Molto agitato 7 Sehr fliessend 8 Lento 9 Largo 10 Sehr fliessend 10a A Tempt 11 Sostenuto 12 Sostenuto, quasi guisto 13 Sostenuto, con slancio 14 Disperato, vivo 15 Larghetto Juilliard String Quartet Joel Smirnoff, violin; Ronald Copes, violin; Samuel Rhodes, viola; Joel Krosnick, cello GEORGE GERSHWIN (1898-1937) arr. PETER STOLTZMAN Porgy and Bess Suite (1935) It Ain’t Necessarily So Prayer Summertime Richard Stoltzman, clarinet and Peter Stoltzman, piano intermission MICHAEL DAUGHERTY (b. 1954) Used Car Salesman (2000) Ethos Percussion Group Trey Files, Eric Phinney, Michael Sgouros, Yousif Sheronick New York Premiere Commissined by Hancher Auditorium/The University of Iowa LEOS JANÁCEK (1854-1928) Mládi (Youth) Suite for Wind Instruments (1924) Allegro Andante sostenuto Vivace Allegro animato Musicians from Marlboro Tanya Dusevic Witek, flute; Rudolph Vrbsky, oboe; Anthony McGill, clarinet; Jo-Ann Sternberg, bass clarinet; Daniel Matsukawa, bassoon; David Jolley, horn ZOLTAN KODALY (1882-1967) String Quartet #2 in D minor, Op. -

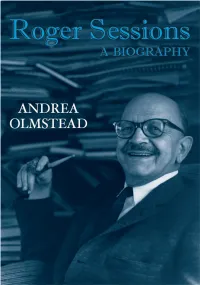

Roger Sessions: a Biography

ROGER SESSIONS: A BIOGRAPHY Recognized as the primary American symphonist of the twentieth century, Roger Sessions (1896–1985) is one of the leading representatives of high modernism. His stature among American composers rivals Charles Ives, Aaron Copland, and Elliott Carter. Influenced by both Stravinsky and Schoenberg, Sessions developed a unique style marked by rich orchestration, long melodic phrases, and dense polyphony. In addition, Sessions was among the most influential teachers of composition in the United States, teaching at Princeton, the University of California at Berkeley, and The Juilliard School. His students included John Harbison, David Diamond, Milton Babbitt, Frederic Rzewski, David Del Tredici, Conlon Nancarrow, Peter Maxwell Davies, George Tson- takis, Ellen Taaffe Zwilich, and many others. Roger Sessions: A Biography brings together considerable previously unpublished arch- ival material, such as letters, lectures, interviews, and articles, to shed light on the life and music of this major American composer. Andrea Olmstead, a teaching colleague of Sessions at Juilliard and the leading scholar on his music, has written a complete bio- graphy charting five touchstone areas through Sessions’s eighty-eight years: music, religion, politics, money, and sexuality. Andrea Olmstead, the author of Juilliard: A History, has published three books on Roger Sessions: Roger Sessions and His Music, Conversations with Roger Sessions, and The Correspondence of Roger Sessions. The author of numerous articles, reviews, program and liner notes, she is also a CD producer. This page intentionally left blank ROGER SESSIONS: A BIOGRAPHY Andrea Olmstead First published 2008 by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY, 10017, USA Simultaneously published in the UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2008 Andrea Olmstead Typeset in Garamond 3 by RefineCatch Limited, Bungay, Suffolk All rights reserved. -

A Heretic in the Schoenberg Circle: Roberto Gerhard's First Engagement with Twelve-Tone Procedures in Andantino

Twentieth-Century Music 16/3, 557–588 © Cambridge University Press 2019. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi: 10.1017/S1478572219000306 A Heretic in the Schoenberg Circle: Roberto Gerhard’s First Engagement with Twelve-Tone Procedures in Andantino DIEGO ALONSO TOMÁS Abstract Shortly before finishing his studies with Arnold Schoenberg, Roberto Gerhard composed Andantino,a short piece in which he used for the first time a compositional technique for the systematic circu- lation of all pitch classes in both the melodic and the harmonic dimensions of the music. He mod- elled this technique on the tri-tetrachordal procedure in Schoenberg’s Prelude from the Suite for Piano, Op. 25 but, unlike his teacher, Gerhard treated the tetrachords as internally unordered pitch-class collections. This decision was possibly encouraged by his exposure from the mid- 1920s onwards to Josef Matthias Hauer’s writings on ‘trope theory’. Although rarely discussed by scholars, Andantino occupies a special place in Gerhard’s creative output for being his first attempt at ‘twelve-tone composition’ and foreshadowing the permutation techniques that would become a distinctive feature of his later serial compositions. This article analyses Andantino within the context of the early history of twelve-tone music and theory. How well I do remember our Berlin days, what a couple we made, you and I; you (at that time) the anti-Schoenberguian [sic], or the very reluctant Schoenberguian, and I, the non-conformist, or the Schoenberguian malgré moi. -

Focus 2020 Pioneering Women Composers of the 20Th Century

Focus 2020 Trailblazers Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century The Juilliard School presents 36th Annual Focus Festival Focus 2020 Trailblazers: Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century Joel Sachs, Director Odaline de la Martinez and Joel Sachs, Co-curators TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction to Focus 2020 3 For the Benefit of Women Composers 4 The 19th-Century Precursors 6 Acknowledgments 7 Program I Friday, January 24, 7:30pm 18 Program II Monday, January 27, 7:30pm 25 Program III Tuesday, January 28 Preconcert Roundtable, 6:30pm; Concert, 7:30pm 34 Program IV Wednesday, January 29, 7:30pm 44 Program V Thursday, January 30, 7:30pm 56 Program VI Friday, January 31, 7:30pm 67 Focus 2020 Staff These performances are supported in part by the Muriel Gluck Production Fund. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment are not permitted in the auditorium. Introduction to Focus 2020 by Joel Sachs The seed for this year’s Focus Festival was planted in December 2018 at a Juilliard doctoral recital by the Chilean violist Sergio Muñoz Leiva. I was especially struck by the sonata of Rebecca Clarke, an Anglo-American composer of the early 20th century who has been known largely by that one piece, now a staple of the viola repertory. Thinking about the challenges she faced in establishing her credibility as a professional composer, my mind went to a group of women in that period, roughly 1885 to 1930, who struggled to be accepted as professional composers rather than as professional performers writing as a secondary activity or as amateur composers. -

Everything Essential

Everythi ng Essen tial HOW A SMALL CONSERVATORY BECAME AN INCUBATOR FOR GREAT AMERICAN QUARTET PLAYERS BY MATTHEW BARKER 10 OVer tONeS Fall 2014 “There’s something about the quartet form. albert einstein once Felix Galimir “had the best said, ‘everything should be as simple as possible, but not simpler.’ that’s the essence of the string quartet,” says arnold Steinhardt, longtime first violinist of the Guarneri Quartet. ears I’ve been around and “It has everything that is essential for great music.” the best way to get students From Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert through the romantics, the Second Viennese School, Debussy, ravel, Bartók, the avant-garde, and up to the present, the leading so immersed in the act of composers of each generation reserved their most intimate expression and genius for that basic ensemble of two violins, a viola, and a cello. music making,” says Steven Over the past century america’s great music schools have placed an increasing emphasis tenenbom. “He was old on the highly specialized and rigorous discipline of quartet playing. among them, Curtis holds a special place despite its small size. In the last several decades alone, among the world and new world.” majority of important touring quartets in america at least one chair—and in some cases four—has been filled by a Curtis-trained musician. (Mr. Steinhardt, also a longtime member of the Curtis faculty, is one.) looking back, the current golden age of string quartets can be traced to a mission statement issued almost 90 years ago by early Curtis director Josef Hofmann: “to hand down through contemporary masters the great traditions of the past; to teach students to build on this heritage for the future.” Mary louise Curtis Bok created a haven for both teachers and students to immerse themselves in music at the highest levels without financial burden. -

Touring Biz Awaits Rap Boom

Y2,500 (JAPAN) $6.95 (U.S.), $8.95 (CAN.), £5.50 (U.K.), 8.95 (EUROPE), II1I11 111111111111 IIIIILlll I !Lull #BXNCCVR 3 -DIGIT 908 #90807GEE374EM002# BLBD 863 A06 B0116 001 MAR 04 2 MONTY GREENLY 3740 ELM AVE # A LONG BEACH CA 90807 -3402 HOME ENTERTAINMENT THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC, VIDEO, AND Labels Hitching Stars To Clive Greeted As New RCA Chief Global Consumer Brands Artists, Managers Heap Praise On Davis, But Some Just Want Stability given five -year contracts, according BY MELINDA NEWMAN BY BRIAN GARRITY Goldstuck had been pres- While managers of acts signed to to Davis. NEW YORK -In the latest sign of J Records. Richard RCA Records are quick to praise out- ident/C00 that the marketing of music is will continue as executive going RCA Music Group (RMG) Sanders undergoing a sea change, the RCA Records. chairman Bob Jamieson, they are also VP /GM of major labels are forging closer ties "We absolutely loved and have heralding the news that J Records with global consumer brands in with Bob Jamieson head Clive Davis will now control enjoyed working an effort to gain exposure for their and hope our paths will cross with him both the J label and RCA Records. acts. As the deals become more says artist manager Irving BMG announced Nov. 19 that it is again," pervasive, they raise questions for whose client Christina Aguilera buying out Davis' 50 %, stake in J Azoff, artists, who have typically cut on RCA Oct. 29. "I've Records -the label he formed in released Stripped their own sponsorship deals. -

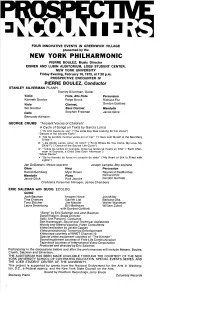

Prospective Encounters

FOUR INNOVATIVE EVENTS IN GREENWICH VILLAGE presented by the NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC PIERRE BOULEZ, Music Director EISNER AND LUBIN AUDITORIUM, LOEB STUDENT CENTER, NEW YORK UNIVERSITY Friday Evening, February 18, 1972, at 7:30 p.m. PROSPECTIVE ENCOUNTER IV PIERRE BOULEZ, Conductor STANLEY SILVERMAN PLANH Stanley Silverman, Guitar Violin Flute, Alto Flute Percussion Kenneth Gordon Paige Brook Richard Fitz Viola Clarinet, Gordon Gottlieb Sol Greitzer Bass Clarinet Mandolin Cello Stephen Freeman Jacob Glick Bernardo Altmann GEORGE CRUMB "Ancient Voices of Children" A Cycle of Songs on Texts by Garcia Lorca I "El niho busca su voz" ("The Little Boy Was Looking for his Voice") "Dances of the Ancient Earth" II "Me he perdido muchas veces por el mar" ("I Have Lost Myself in the Sea Many Times") III "6De d6nde vienes, amor, mi nino?" ("From Where Do You Come, My Love, My Child?") ("Dance of the Sacred Life-Cycle") IV "Todas ]as tardes en Granada, todas las tardes se muere un nino" ("Each After- noon in Granada, a Child Dies Each Afternoon") "Ghost Dance" V "Se ha Ilenado de luces mi coraz6n de seda" ("My Heart of Silk Is Filled with Lights") Jan DeGaetani, Mezzo-soprano Joseph Lampke, Boy soprano Oboe Harp Percussion Harold Gomberg Myor Rosen Raymond DesRoches Mandolin Piano Richard Fitz Jacob Glick PaulJacobs Gordon Gottlieb Orchestra Personnel Manager, James Chambers ERIC SALZMAN with QUOG ECOLOG QUOG Josh Bauman Imogen Howe Jon Miller Tina Chancey Garrett List Barbara Oka Tony Elitcher Jim Mandel Walter Wantman Laura Greenberg Bill Matthews -

Sfkieherd Sc~Ol Ofmusic

GUEST ARTIST RECITAL JEFFREY JACOB, Piano Thursday, September 18, 2008 8:00 p.m. Lillian H. Duncan Recital Hall sfkieherd RICE UNIVERSITY Sc~ol ofMusic PROGRAM Makrokosmos II George Crumb Twelve Fantasy-Pieces after the Zodiac (b.1929) (for amplified piano) 1. Morning Music (Genesis II) 2. The Mystic Chord 3. Rain-Death Variations 4. Twin Suns (Doppelganger aus der Ewigkeit) 5. Ghost-Nocturne: For the Druids of Stonehenge 6. Gargoyles 7. Tora I Tora I Tora I ( Cadenza Apocalittica) 8. A Prophecy of Nostradamus 9. Cosmic Wind 10. Voices from "Corona Borealis" 11. Litany of the Galactic Bells 12. Agnus Dei The reverberative acoustics of Duncan Recital Hall magnify the slightest sound made by the audience. Your care and courtesy will be appreciated. The taking ofphotographs and use ofrecording equipment are prohibited. BIOGRAPHY Described by the Warsaw Music Journal as "unquestionably one of the greatest performers of 20th-century music," and the New York Times as "an artist ofintense concentration and conviction," Jeffrey Jacob re ceived his education from the Juilliard School (Master of Music) and the Peabody Conservatory (Doctor ofMusical Arts) and counts as his prin cipal teachers Mieczyslaw Munz, Carlo Zecchi, and Leon Fleisher. Since his debut with the London Philharmonic in Royal Festival Hall, he has appeared as piano soloist with over twenty orchestras internationally including the Moscow, St. Petersburg, Seattle, Portland, Indianapolis, Charleston, Silo Paulo and Brazilian National Symphonies, and the Si lesian, Moravian , North Czech, and Royal Queenstown Philharmonics. A noted proponent ofcontemporary music, he has performed the world premieres of works written for him by George Crumb, Gunther Schuller, Vincent Persichetti, Samuel Adler, Francis Routh, and many others. -

Apple Hill String Quartet

Apple Hill String Quartet The Apple Hill String Quartet has earned accolades from around the world for their interpretive mastery of such traditional repertoire as Haydn, Mozart, Schubert, Schumann, Beethoven, and Ravel — along with their special dedication to seldom heard masterworks and contemporary music. They have performed concerts extensively throughout the United States, Europe, the Middle East, and Asia as part of Apple Hill’s innovative Playing for Peace™ program. Education is an integral part of the quartet’s mission — therefore they have conducted mini- residencies in embassies, communities, schools and universities locally in the Monadnock region, nationally in the major U.S. cities, and throughout the world in such faraway places as Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Israel, Palestine, Algiers, Cyprus, Ireland, England, Burma, Vietnam, Malaysia, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Georgia, and Russia. They also spend countless hours as dedicated teacher-performers at Apple Hill’s renowned Summer Chamber Music Workshop, held each summer on the 100-acre Apple Hill campus. As 21st-century musicians, the quartet is deeply committed to the commissioning of new works. Their recent commission by composer and long-time “Apple Hiller” Daniel Sedgwick was premiered at Apple Hill in 2009 and performed to critical acclaim throughout the U.S., Europe, and the Middle East. Their project, “Around the World with Playing for Peace™", features the rich multicultural repertoire of works and compositions associated with countries visited through the Playing for Peace™ program, as seen through the lens of the string quartet. Featured composers have included Victor Ullman (String Quartet #3, written in the Theresienstadt Concentration Camp), Turkish composer Ekrem Zeki Ün, Armenian composers Alan Hovhaness and A. -

Paper 59 2019.Pdf

1 Accademia Musicale Studio Musica International Conference on New Music Concepts and Inspired Education Proceeding Book Vol. 6 Accademia Musicale Studio Musica Michele Della Ventura Editor COPYRIGHT MATERIAL 2 Printed in Italy First edition: April 2019 ©2019 Accademia Musicale Studio Musica www.studiomusicatreviso.it Accademia Musicale Studio Musica – Treviso (Italy) ISBN: 978-88-944350-0-9 3 Preface This volume of proceedings from the conference provides an opportunity for readers to engage with a selection of refereed papers that were presented during the International Conference on New Music Concepts and Inspired Education. The reader will sample here reports of research on topics ranging from mathematical models in music to pattern recognition in music; symbolic music processing; music synthesis and transformation; learning and conceptual change; teaching strategies; e-learning and innovative learning. This book is meant to be a textbook that is suitable for courses at the advanced under- graduate and beginning master level. By mixing theory and practice, the book provides both profound technological knowledge as well as a comprehensive treatment of music processing applications. The goals of the Conference are to foster international research collaborations in the fields of Music Studies and Education as well as to provide a forum to present current research results in the forms of technical sessions, round table discussions during the conference period in a relax and enjoyable atmosphere. 36 papers from 16 countries were received. All the submissions were reviewed on the basis of their significance, novelty, technical quality, and practical impact. After careful reviews by at least three experts in the relevant areas for each paper, 12 papers from 10 countries were accepted for presentation or poster display at the conference. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1963-1964

TANGLEWOOD Festival of Contemporary American Music August 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 1964 Sponsored by the Berkshire Music Center In Cooperation with the Fromm Music Foundation RCA Victor R£D SEAL festival of Contemporary American Composers DELLO JOIO: Fantasy and Variations/Ravel: Concerto in G Hollander/Boston Symphony Orchestra/Leinsdorf LM/LSC-2667 COPLAND: El Salon Mexico Grofe-. Grand Canyon Suite Boston Pops/ Fiedler LM-1928 COPLAND: Appalachian Spring The Tender Land Boston Symphony Orchestra/ Copland LM/LSC-240i HOVHANESS: BARBER: Mysterious Mountain Vanessa (Complete Opera) Stravinsky: Le Baiser de la Fee (Divertimento) Steber, Gedda, Elias, Mitropoulos, Chicago Symphony/Reiner Met. Opera Orch. and Chorus LM/LSC-2251 LM/LSC-6i38 FOSS: IMPROVISATION CHAMBER ENSEMBLE Studies in Improvisation Includes: Fantasy & Fugue Music for Clarinet, Percussion and Piano Variations on a Theme in Unison Quintet Encore I, II, III LM/LSC-2558 RCA Victor § © The most trusted name in sound BERKSHIRE MUSIC CENTER ERICH Leinsdorf, Director Aaron Copland, Chairman of the Faculty Richard Burgin, Associate Chairman of the Faculty Harry J. Kraut, Administrator FESTIVAL of CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN MUSIC presented in cooperation with THE FROMM MUSIC FOUNDATION Paul Fromm, President Alexander Schneider, Associate Director DEPARTMENT OF COMPOSITION Aaron Copland, Head Gunther Schuller, Acting Head Arthur Berger and Lukas Foss, Guest Teachers Paul Jacobs, Fromm Instructor in Contemporary Music Stanley Silverman and David Walker, Administrative Assistants The Berkshire Music Center is the center for advanced study in music sponsored by the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Erich Leinsdorf, Music Director Thomas D. Perry, Jr., Manager BALDWIN PIANO RCA VICTOR RECORDS — 1 PERSPECTIVES OF NEW MUSIC Participants in this year's Festival are invited to subscribe to the American journal devoted to im- portant issues of contemporary music. -

Crumb, George | Grove Music

Grove Music Online Crumb, George (Henry ) Richard Steinitz https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.A2249252 Published in print: 26 November 2013 Published online: 16 October 2013 (b Charleston, WV, Oct 24, 1929). American composer. Born to accomplished musical parents, he participated in domestic music- making from an early age, an experience that instilled a lifelong empathy with the Classical and Romantic repertory, as his Three Early Songs (1947) exemplify. He studied at Mason College (1947– 50), the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign (MM 1953), the Berlin Hochschule für Musik (Fulbright Fellow, 1955–6), where he was a student of Boris Blacher, and the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor (DMA 1959), where his teachers included Ross Lee Finney. At Ann Arbor, Crumb encountered the poetry of Federico García Lorca and listened with fellow students to Folkways recordings of world music. Debussy and Mahler were early influences, as well as Ives and the hymnody and revival songs in which Crumb was also immersed. But it was European music from Stravinsky and Ravel to the Second Viennese School and Dallapiccola that is reflected in his first significant composition, Variazioni (1959) for large orchestra, in a synthesis never doctrinaire, but sophisticated and transparent, displaying already an acute sensitivity to color. In the year of its completion, Crumb accepted a post at the University of Colorado, Boulder (1959–64) where, although employed as a piano teacher, his first mature works were composed. These include Five Pieces for Piano (1962), Night Music I (1963), which began as an instrumental composition but “came into focus” when he decided to set two poems by Lorca, and Four Nocturnes (1964).