ORCHESTRA 2001 Ann Crumb, Soprano & Patrick Mason, Baritone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marvin Gaye As Vocal Composer 63 Andrew Flory

Sounding Out Pop Analytical Essays in Popular Music Edited by Mark Spicer and John Covach The University of Michigan Press • Ann Arbor Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2010 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid-free paper 2013 2012 2011 2010 4321 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sounding out pop : analytical essays in popular music / edited by Mark Spicer and John Covach. p. cm. — (Tracking pop) Includes index. ISBN 978-0-472-11505-1 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-472-03400-0 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Popular music—History and criticism. 2. Popular music— Analysis, appreciation. I. Spicer, Mark Stuart. II. Covach, John Rudolph. ML3470.S635 2010 781.64—dc22 2009050341 Contents Preface vii Acknowledgments xi 1 Leiber and Stoller, the Coasters, and the “Dramatic AABA” Form 1 john covach 2 “Only the Lonely” Roy Orbison’s Sweet West Texas Style 18 albin zak 3 Ego and Alter Ego Artistic Interaction between Bob Dylan and Roger McGuinn 42 james grier 4 Marvin Gaye as Vocal Composer 63 andrew flory 5 A Study of Maximally Smooth Voice Leading in the Mid-1970s Music of Genesis 99 kevin holm-hudson 6 “Reggatta de Blanc” Analyzing -

Percussion Ensemble Spring Concert

Kennesaw State University THE GSO College of the Arts APPLAUDS THE School of Music KSU SCHOOL OF MUSIC! presents Thank you for fostering the future of our students Percussion Ensemble and their heritage of Spring Concert the arts. John Lawless, director Photo: Tom Kells Photo: Tom Call us at 770-429-7016 Visit us at georgiasymphony.org Monday, April 28, 2014 8:00 p.m. Audrey B. and Jack E. Morgan, Sr. Concert Hall Dr. Bobbie Bailey & Family Performance Center One Hundred Twenty-seventh Concert of the 2013-14 Concert Season CopelandsKSU_0713_CopelandsKSU_0713 7/5/13 Program LYNN GLASSOCK (b.1946) Street Talk Famous New Orleans Style Food and USDA JOHN PSATHAS (b.1966) PRIME One Summary Erik Kosman, marimba solo BOB BECKER (b.1947) Prisoners of the Image Factory Selena Sanchez Featuring New Orleans Live Jazz Natasha Black Sunday Brunch Music PM AM to 3 Served from Levi Lyman From 11 Buffet 10 AM to 3 PM KENNESAW•770-919-9612 1142 Ernest W.Barrett Pkwy.,NW LORENZO SANFORD (b.1962) www.CopelandsAtlanta.com A Leap Of Faith JOHN CAGE (1912-1992) Credo In US Erik Kosman Cameron Austin Janna Graham Judy Cole, piano ROBERT MARINO (unknown) Eight on 3 and Nine on 2 Levi Lyman Kyle Pridgen Uncle Maddio’s Pizza Joint BLAKE TYSON (unknown) 745 Chastain Road Not Far From Here Next to Starbucks & Firehouse Subs 770-573-1694 Percussion Ensemble Personnel Cameron Austin Levi Lyman Natasha Black Kyle Pridgen Janna Graham Selena Sanchez Sydney Hunter Jada Taylor Erik Kosman Program Notes Street Talk LYNN GLASSOCK (b.1946) Lyn Glassock is one of the most prolific composers for the percussion ensemble living today. -

What Do Your Dreams Sound Like?

Volume 6 › 2017 Orchestral, Concert & Marching Edition What do your Dreams sound like? PROBLEM SOLVED WHY DREAM? D R E A M 2 0 1 7 1 D R E A M 2 0 1 7 Attention Band Directors, Music Teachers, “The Cory Band have been the World's No.1 brass band for the past decade. We feel privileged Orchestra Conductors! to have been associated with We understand how frustrating it can be to try to find the professional Dream Cymbals since 2014. quality, exceptionally musical sounds that you need at a price that fits into From the recording studio to your budget. Everyone at Dream is a working musician so we understand the challenges from our personal experiences. You should not have to Rick Kvistad of the concert halls across the UK and sacrifice your sound quality because of a limited budget. San Francisco Opera says: abroad, we have come to rely From trading in your old broken cymbals through our recycling program, on the Dream sound week in putting together custom tuned gong sets, or creating a specific cymbal set “I love my Dream Cymbals up that we know will work with your ensemble, we love the challenge of week out.” creating custom solutions. for both the orchestra and Visit dreamcymbals.com/problemsolved and get your personal cymbal assistant. By bringing together our network of exceptional dealers and our my drum set. Dr. Brian Grasier, Adjunct Instructor, Percussion, in-house customer service team, we can provide a custom solution tailored They have a unique Sam Houston State University says: to your needs, for free. -

History, Development and Tuning of the Hang

ISMA 2007 Hang HISTORY, DEVELOPMENT AND TUNING OF THE HANG Felix Rohner and Sabina Schärer PANArt Hangbau AG, Engehaldenstr.131, 3012 Bern, Switzerland Abstract The HANG is a new musical instrument, suitable for playing with the hands, consisting of two hemispherical shells of nitrided steel. It is the product of a collaboration among scientists, engineers and hangmakers, thanks to which we have been able to better understand the tuning process in all its complexity. Seven notes are harmonically tuned around a central deep tone (ding), which excites the Helmholtz (cavity) resonance of the body of the instrument. There are many ways to play the HANG. We show the different stages of its development over the seven years since its birth in 2000. We describe the tuning process and the musical conception of the HANG. INTRODUCTION The HANG was created in January 2000 by the tuners of PANArt Hangbau AG, formerly Steelpan Manufacture AG, Bern, Switzerland. It came out of twenty-five years of manufacturing the steelpan and research on its technology and acoustics. The youngest member of the family of acoustic musical instruments, the HANG is the result of a marriage between art and science. Five thousand HANG players worldwide and an ever-increasing demand show the deep resonance this instrument has with individuals. As we are only two hangmakers, our interest here is to invite scientists to continue working together to better understand this phenomenon. FROM STEELPAN TO HANG PANArt Hangbau AG was founded in 1993 to give cultural and commercial support to the growing steelband movement in Switzerland. -

The Songs of Michael Head: the Georgian Settings (And Song Catalogue)

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1990 The onS gs of Michael Head: The Georgian Settings (And Song Catalogue). Loryn Elizabeth Frey Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Frey, Loryn Elizabeth, "The onS gs of Michael Head: The Georgian Settings (And Song Catalogue)." (1990). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 4985. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/4985 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Copy UPDATED KAREOKE 2013

Artist Song Title Disc # ? & THE MYSTERIANS 96 TEARS 6781 10 YEARS THROUGH THE IRIS 13637 WASTELAND 13417 10,000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT 9703 CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS 1693 LIKE THE WEATHER 6903 MORE THAN THIS 50 TROUBLE ME 6958 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL SOMEBODY'S BEEN SLEEPING 5612 10CC I'M NOT IN LOVE 1910 112 DANCE WITH ME 10268 PEACHES & CREAM 9282 RIGHT HERE FOR YOU 12650 112 & LUDACRIS HOT & WET 12569 1910 FRUITGUM CO. 1, 2, 3 RED LIGHT 10237 SIMON SAYS 7083 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 3847 CHANGES 11513 DEAR MAMA 1729 HOW DO YOU WANT IT 7163 THUGZ MANSION 11277 2 PAC & EMINEM ONE DAY AT A TIME 12686 2 UNLIMITED DO WHAT'S GOOD FOR ME 11184 20 FINGERS SHORT DICK MAN 7505 21 DEMANDS GIVE ME A MINUTE 14122 3 DOORS DOWN AWAY FROM THE SUN 12664 BE LIKE THAT 8899 BEHIND THOSE EYES 13174 DUCK & RUN 7913 HERE WITHOUT YOU 12784 KRYPTONITE 5441 LET ME GO 13044 LIVE FOR TODAY 13364 LOSER 7609 ROAD I'M ON, THE 11419 WHEN I'M GONE 10651 3 DOORS DOWN & BOB SEGER LANDING IN LONDON 13517 3 OF HEARTS ARIZONA RAIN 9135 30 SECONDS TO MARS KILL, THE 13625 311 ALL MIXED UP 6641 AMBER 10513 BEYOND THE GREY SKY 12594 FIRST STRAW 12855 I'LL BE HERE AWHILE 9456 YOU WOULDN'T BELIEVE 8907 38 SPECIAL HOLD ON LOOSELY 2815 SECOND CHANCE 8559 3LW I DO 10524 NO MORE (BABY I'MA DO RIGHT) 178 PLAYAS GON' PLAY 8862 3RD STRIKE NO LIGHT 10310 REDEMPTION 10573 3T ANYTHING 6643 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP 1412 4 P.M. -

KASHCHEI for Nine Instruments and Electronics

KASHCHEI For Nine Instruments and Electronics Nina C. Young November 2010 KASHCHEI for nine instruments and electronics November 2010 Approximate duration: 18:00 Premiered February 8, 2011, Live@CIRMMT – Montreal, Canada Instrumentation: Program Notes: flute (+ piccolo) Kashchei, for nine instruments and electronics, was written by Nina C. Young in 2010 in partial fulfillment of the Master’s of Music degree at McGill University under the supervision of Prof. Sean clarinet in B (+ bass clarinet) b Ferguson. The piece is a representation of Kashchei – a character from Russian folklore who makes an trumpet in C (+ piccolo trumpet; straight and harmon mutes) appearance in many popular fairytales or skazki. H is a dark, evil person of ugly, senile appearance who principally menaces young women. Kashchei cannot be killed by conventional means targeting his body. 2 percussion: Rather, the essence of his life is hidden outside of his flesh in a needle within an egg. Only by finding this I – vibraphone egg and breaking the needle can one overcome Kashchei’s powers. In one skazka, the princess Tsarevna’s I – almglocken (F4, G#4, A4, C5, D#5, E5, F5, G5, A5, B5, C#6) Darissa asks Kashchei where his death lies. Infatuated by her beauty, he let’s down his guard and I – crotales (E5, F5) eventually explains, “My death is far from hence, and hard to find, on the ocean wide: in that sea is the island of I – triangle I – wind chime Buyan, and upon this island there grows a green oak, and beneath this oak is an iron chest, and in this chest is a small I – splash cymbal basket, and in this basket is a hare, and in this hare is a duck, and in this duck is an egg; and he who finds this egg and I – suspended cymbal (medium) breaks it, at the same instant causes my death.” My own piece explores the seven layers and death of Kashchei. -

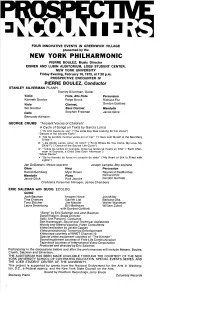

Prospective Encounters

FOUR INNOVATIVE EVENTS IN GREENWICH VILLAGE presented by the NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC PIERRE BOULEZ, Music Director EISNER AND LUBIN AUDITORIUM, LOEB STUDENT CENTER, NEW YORK UNIVERSITY Friday Evening, February 18, 1972, at 7:30 p.m. PROSPECTIVE ENCOUNTER IV PIERRE BOULEZ, Conductor STANLEY SILVERMAN PLANH Stanley Silverman, Guitar Violin Flute, Alto Flute Percussion Kenneth Gordon Paige Brook Richard Fitz Viola Clarinet, Gordon Gottlieb Sol Greitzer Bass Clarinet Mandolin Cello Stephen Freeman Jacob Glick Bernardo Altmann GEORGE CRUMB "Ancient Voices of Children" A Cycle of Songs on Texts by Garcia Lorca I "El niho busca su voz" ("The Little Boy Was Looking for his Voice") "Dances of the Ancient Earth" II "Me he perdido muchas veces por el mar" ("I Have Lost Myself in the Sea Many Times") III "6De d6nde vienes, amor, mi nino?" ("From Where Do You Come, My Love, My Child?") ("Dance of the Sacred Life-Cycle") IV "Todas ]as tardes en Granada, todas las tardes se muere un nino" ("Each After- noon in Granada, a Child Dies Each Afternoon") "Ghost Dance" V "Se ha Ilenado de luces mi coraz6n de seda" ("My Heart of Silk Is Filled with Lights") Jan DeGaetani, Mezzo-soprano Joseph Lampke, Boy soprano Oboe Harp Percussion Harold Gomberg Myor Rosen Raymond DesRoches Mandolin Piano Richard Fitz Jacob Glick PaulJacobs Gordon Gottlieb Orchestra Personnel Manager, James Chambers ERIC SALZMAN with QUOG ECOLOG QUOG Josh Bauman Imogen Howe Jon Miller Tina Chancey Garrett List Barbara Oka Tony Elitcher Jim Mandel Walter Wantman Laura Greenberg Bill Matthews -

Sfkieherd Sc~Ol Ofmusic

GUEST ARTIST RECITAL JEFFREY JACOB, Piano Thursday, September 18, 2008 8:00 p.m. Lillian H. Duncan Recital Hall sfkieherd RICE UNIVERSITY Sc~ol ofMusic PROGRAM Makrokosmos II George Crumb Twelve Fantasy-Pieces after the Zodiac (b.1929) (for amplified piano) 1. Morning Music (Genesis II) 2. The Mystic Chord 3. Rain-Death Variations 4. Twin Suns (Doppelganger aus der Ewigkeit) 5. Ghost-Nocturne: For the Druids of Stonehenge 6. Gargoyles 7. Tora I Tora I Tora I ( Cadenza Apocalittica) 8. A Prophecy of Nostradamus 9. Cosmic Wind 10. Voices from "Corona Borealis" 11. Litany of the Galactic Bells 12. Agnus Dei The reverberative acoustics of Duncan Recital Hall magnify the slightest sound made by the audience. Your care and courtesy will be appreciated. The taking ofphotographs and use ofrecording equipment are prohibited. BIOGRAPHY Described by the Warsaw Music Journal as "unquestionably one of the greatest performers of 20th-century music," and the New York Times as "an artist ofintense concentration and conviction," Jeffrey Jacob re ceived his education from the Juilliard School (Master of Music) and the Peabody Conservatory (Doctor ofMusical Arts) and counts as his prin cipal teachers Mieczyslaw Munz, Carlo Zecchi, and Leon Fleisher. Since his debut with the London Philharmonic in Royal Festival Hall, he has appeared as piano soloist with over twenty orchestras internationally including the Moscow, St. Petersburg, Seattle, Portland, Indianapolis, Charleston, Silo Paulo and Brazilian National Symphonies, and the Si lesian, Moravian , North Czech, and Royal Queenstown Philharmonics. A noted proponent ofcontemporary music, he has performed the world premieres of works written for him by George Crumb, Gunther Schuller, Vincent Persichetti, Samuel Adler, Francis Routh, and many others. -

Aulis Sallinen: a Catalogue of the Orchestral and Choral Music

AULIS SALLINEN: A CATALOGUE OF THE ORCHESTRAL AND CHORAL MUSIC 1956: Two Mythical Scenes for Orchestra, op.1: 12 minutes 1959-60: Concerto for Chamber Orchestra, op.3: 22 minutes 1961: Variations for Cello and Orchestra, op.5: 18 minutes 1962: Three Lyrical Songs of Death for baritone, male choir and chamber orchestra, op.6: 15 minutes “Mauermusik” for orchestra, op.7: 9 minutes + (cpo cd) 1963: Variations for Orchestra, op.8: 10 minutes + (BIS cd) 1964: Metamorphosen for Piano and Chamber Orchestra: 20 minutes 1967: Ballet “Variations sur Mallarme”, op. 16: 24 minutes 1968: Violin Concerto, op.18: 18 minutes + (BIS and cpo cds) 1969/1981: “Some Aspects of Peltoniemi Hintrik’s Funeral March” for string orchestra, op. 19: 12 minutes + (Finlandia and BIS cds) 1970: “Chorali” for winds, percussion, harp and celeste, op.22: 11 minutes + (BIS and cpo cds) 1971: Symphony No.1, op. 24: 16 minutes + (BIS and cpo cds) “Suite grammaticale” for children’s choir and chamber orchestra, op.28: 14 minutes + (Ondine cd) 1972: Symphony No.2 “Symphonic Dialogue” for percussion and orchestra, op. 29: 16 minutes + (BIS and cpo cds) 1972-73: Four Dream Songs (from the Opera “The Horseman”) for soprano and orchestra, op. 30: 12 minutes + (BIS cd) 1975: Symphony No.3, op.35: 23 minutes + (BIS and cpo cds) Chamber Music I for string orchestra, op.38: 11 minutes + (Finlandia and BIS cds) 1976: Chamber Music II for alto flute and string orchestra, op.41: 13 minutes + (BIS cd) Cello Concerto, op.44: 25 minutes + (Finlandia and cpo cds) 1976-78: “Simana Arhippaini’s -

FMP FREE MUSIC PRODUCTION Distribution & Communication Markgraf-Albrecht-Str

Mary Oliver w ww.oliverheggen.com Mary Oliver (violin, viola, hardanger fiddle) was born in La Jolla, California, and studied at San Francisco State University (Bachelor of Music), Mills College (Master of Fine Arts) and the University of California, San Diego where she received her Ph.D in 1993 for her research in the theory and practice of improvised music. Her work as a soloist encompasses both composed and improvised contemporary music; she has premiered works by among others,Richard Barrett, John Cage, Chaya Czernowin, Brian Ferneyhough, Joëlle Léandre Liza Lim, George E. Lewis , Richard Teitelbaum and Iannis Xenakis . Oliver has worked alongside improvising musicians such as Han Bennink, Mark Dresser, Cor Fuhler, Jean-Charles François, Tristan Honsinger, Joëlle Léandre, George E. Lewis, Nicole Mitchell, Andy Moor, Misha Mengelberg Evan Parker, and Anthony Pateras. As a soloist and ensemble player she has performed in numerous international festivals including the Darmstädter Ferienkurse für Neue Musik ,Donaueschinger Musiktage 2002, Bimhuis October Meeting, Vancouver and Toronto Jazz Festivals, Ars Electronica , Ars Musica, London Musicians Collective Festival, Münchner Biennale, Salzburger Festspiele and MaerzMusik Festival in Berlin. In 1994, she was an artist in residence at Akademie Schloss Solitude in Stuttgart where she added, through their generosity, the hardinger fiddle to her instrumentarium. For the past twelve years she has been based in Amsterdam where she has worked locally and internationally with various ensembles such as Instant Composer’s Pool (ICP) Orchestra, Magpie Music and Dance Company, AACM Black Earth Ensemble, Scapino Ballet , Elision Ensemble, MAE, Het National Ballet and Xenakis Ensemble. Currently she teaches at the Hogeschol voor Kunst, Media en Technology and a member of ICP Orchestra, Ammü (with Han Bennink, Johanna Varner, cello and Christofer Varner – trombone) and Magpie Music Dance Company. -

Download the Instrument List

Cinekinetik Instrument list 4 Libraries - 295 Instrument presets CineKinetik: Shipwreck Piano 33 Instrument presets SW Upright Piano SW Upright Piano Soft SW Upright Piano Mellow SW Upright Piano Hard SW Upright Piano Dark Shipwreck Piano Shipwreck Piano Quantum Room Shipwreck Piano Quantum Minute Shipwreck Piano Quantum Hall Shipwreck Piano Mellow Shipwreck Piano Quantum Church Shipwreck Piano Hard Shipwreck Piano Dark Shipwreck X Phase Whistle Shipwreck X Pad Shipwreck X Phase Dark Shipwreck X Pad Decay Shipwreck X Pad Jet Shipwreck X Pad Watery Shipwreck Swell Pad Dark Shipwreck Swell Pad Warm Shipwreck Swell Pad Shipwreck X Atmosphere Shipwreck X Lo-Fi Hit Shipwreck Quantum Pad Warm Shipwreck Quantum Pad Watery Shipwreck Quantum Pad Phase Shipwreck Quantum Pad Slow Shipwreck Quantum Pad Fast Shipwreck Quantum Pad Dark Shipwreck Russian Choir 2 Shipwreck Russian Choir 1 Shipwreck X Ligeti Wind 1 Cinekinetik Instrument list CineKinetik: Fractured Piano 37 Instrument presets 1914 Phantom Tron 1980 PG Tron Acid Mallets Angry Tony B Bounty Hunters MW Boys Of The Belt MW Deep Ocean Waves Electrified Piano Doom MW Funky Electric Hourglass I Can Sea Clearly Key attack from space Lo-Fi Chase piano Mothers Of The Belt Percussive and Electrified MW Piano Chain 2 MW Piano Chain Brass Piano Chain Tremolo Piano Chain Piano Felt Bass MW Piano Felt Bass Pluck 4th Piano Felt Pedal Piano Howlings B Piano Howlings C Piano Howlings Piano Metal Bar Bass Piano Metal Bar MW Poseidon Waves Space Station Lounge MW Stalker The Arrival The Camera Eye The Departure