John Cage: the Text Pieces I 23

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seattle Opera Announces 2021/22 Season— a Return to Live, In-Person Performances

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: May 11, 2021 Contact: Gabrielle Gainor (206) 295-0998, [email protected] Press images: https://seattleopera.smugmug.com/2122 Password: “press” Seattle Opera announces 2021/22 season— a return to live, in-person performances La bohème Orpheus and Eurydice Blue The Marriage of Figaro Plus a special recital by Lawrence Brownlee McCaw Hall and The Opera Center Subscriptions begin at $240 (BRAVO! Club, senior, and student pricing is also available). Single tickets will go on sale closer to each production. seattleopera.org SEATTLE—After more than a year without live, in-person performances due to COVID-19, Seattle Opera will officially return to the theater this fall with its 2021/22 Season. Offerings include immortal favorites (La bohème, The Marriage of Figaro), historic works with a modern twist (Orpheus and Eurydice), plus an award-winning piece speaking to racial injustice in America (Blue). It will take years for Seattle Opera—and the arts sector as a whole—to recover from the pandemic’s economic impact. Feeling the presence and excitement of live performance again is one way that the healing can begin, said General Director Christina Scheppelmann. “The theater, where music, storytelling, lights, performers, and audiences meet, is a space of magic and impact,” Scheppelmann said. “This past year has been difficult and challenging on so many levels. As we process all that we’ve been through, we can come here to enjoy ourselves. We can rediscover the positive moment and outlook we are seeking. Through opera, we can reconnect with our deepest emotions and our shared humanity.” In addition to mainstage productions, the company will offer a special, one-night- only recital by tenor Lawrence Brownlee (April 29, 2022, at McCaw Hall) with pianist John Keene. -

Amjad Ali Khan & Sharon Isbin

SUMMER 2 0 2 1 Contents 2 Welcome to Caramoor / Letter from the CEO and Chairman 3 Summer 2021 Calendar 8 Eat, Drink, & Listen! 9 Playing to Caramoor’s Strengths by Kathy Schuman 12 Meet Caramoor’s new CEO, Edward J. Lewis III 14 Introducing in“C”, Trimpin’s new sound art sculpture 17 Updating the Rosen House for the 2021 Season by Roanne Wilcox PROGRAM PAGES 20 Highlights from Our Recent Special Events 22 Become a Member 24 Thank You to Our Donors 32 Thank You to Our Volunteers 33 Caramoor Leadership 34 Caramoor Staff Cover Photo: Gabe Palacio ©2021 Caramoor Center for Music & the Arts General Information 914.232.5035 149 Girdle Ridge Road Box Office 914.232.1252 PO Box 816 caramoor.org Katonah, NY 10536 Program Magazine Staff Caramoor Grounds & Performance Photos Laura Schiller, Publications Editor Gabe Palacio Photography, Katonah, NY Adam Neumann, aanstudio.com, Design gabepalacio.com Tahra Delfin,Vice President & Chief Marketing Officer Brittany Laughlin, Director of Marketing & Communications Roslyn Wertheimer, Marketing Manager Sean Jones, Marketing Coordinator Caramoor / 1 Dear Friends, It is with great joy and excitement that we welcome you back to Caramoor for our Summer 2021 season. We are so grateful that you have chosen to join us for the return of live concerts as we reopen our Venetian Theater and beautiful grounds to the public. We are thrilled to present a full summer of 35 live in-person performances – seven weeks of the ‘official’ season followed by two post-season concert series. This season we are proud to showcase our commitment to adventurous programming, including two Caramoor-commissioned world premieres, three U.S. -

Harvey Milk Page 1 of 3 Opera Assn

San Francisco Orpheum 1996-1997 Harvey Milk Page 1 of 3 Opera Assn. Theatre Production made possible by a generous grant from Madeleine Haas Russell. Harvey Milk (in English) Opera in three acts by Stewart Wallace Libretto by Michael Korie Commissioned by S. F. Opera, Houston Grand Opera, and New York City Opera The commission for "Harvey Milk" has been funded in substantial part by a generous gift from Drs. Dennis and Susan Carlyle and has been supported by major grants from the Lila Wallace-Reader's Digest Opera for a New America, a project of OPERA America; the Caddell & Conwell Foundation for the Arts; as well as the National Endowment for the Arts. Conductor CAST Donald Runnicles Harvey Milk Robert Orth Production Messenger James Maddalena Christopher Alden Mama Elizabeth Bishop Set designer Young Harvey Adam Jacobs Paul Steinberg Dan White Raymond Very Costume Designer Man at the opera James Maddalena Gabriel Berry Gidon Saks Lighting Designer Bradley Williams Heather Carson Randall Wong Sound Designer William Pickersgill Roger Gans Richard Walker Chorus Director Man in a tranch coat/Cop Raymond Very Ian Robertson Central Park cop David Okerlund Choreographer Joe Randall Wong Ross Perry Jack Michael Chioldi Realized by Craig Bradley Williams Victoria Morgan Beard Juliana Gondek Musical Preparation Mintz James Maddalena Peter Grunberg Horst Brauer Gidon Saks Bryndon Hassman Adelle Eslinger Scott Smith Bradley Williams Kathleen Kelly Concentration camp inmate Randall Wong Ernest Fredric Knell James Maddalena Synthesizer Programmer -

2016 Program Booklet

Rebecca Penneys Piano Festival Fourth Year July 12 – 30, 2016 University of South Florida, School of Music 4202 East Fowler Avenue, Tampa, FL The family of Steinway pianos at USF was made possible by the kind assistance of the Music Gallery in Clearwater, Florida Rebecca Penneys Ray Gottlieb, O.D., Ph.D President & Artistic Director Vice President Rebecca Penneys Friends of Piano wishes to give special thanks to: The University of South Florida for such warm hospitality, USF administration and staff for wonderful support and assistance, Glenn Suyker, Notable Works Inc., for piano tuning and maintenance, Christy Sallee and Emily Macias, for photos and video of each special moment, and All the devoted piano lovers, volunteers, and donors who make RPPF possible. The Rebecca Penneys Piano Festival is tuition-free for all students. It is supported entirely by charitable tax-deductible gifts made to Rebecca Penneys Friends of Piano Incorporated, a non-profit 501(c)(3). Your gifts build our future. Donate on-line: http://rebeccapenneyspianofestival.org/ Mail a check: Rebecca Penneys Friends of Piano P.O. Box 66054 St Pete Beach, Florida 33736 Become an RPPF volunteer, partner, or sponsor Email: [email protected] 2 FACULTY PHOTOS Seán Duggan Tannis Gibson Christopher Eunmi Ko Harding Yong Hi Moon Roberta Rust Thomas Omri Shimron Schumacher D mitri Shteinberg Richard Shuster Mayron Tsong Blanca Uribe Benjamin Warsaw Tabitha Columbare Yueun Kim Kevin Wu Head Coordinator Assistant Assistant 3 STUDENT PHOTOS (CONTINUED ON P. 51) Rolando Mijung Hannah Matthew Alejandro An Bossner Calderon Haewon David Natalie David Cho Cordóba-Hernández Doughty Furney David Oksana Noah Hsiu-Jung Gatchel Germain Hardaway Hou Jingning Minhee Jinsung Jason Renny Huang Kang Kim Kim Ko 4 CALENDAR OF EVENTS University of South Florida – School of Music Concerts and Masterclasses are FREE and open to the public Donations accepted at the door Festival Soirée Concerts – Barness Recital Hall, see p. -

Oceanic Migrations

San Francisco Contemporary Music Players on STAGE series Oceanic Migrations MICHAEL GORDON ROOMFUL OF TEETH SPLINTER REEDS September 14, 2019 Cowell Theater Fort Mason Cultural Center San Francisco, CA SFCMP SAN FRANCISCO CONTEMPORARY MUSIC PLAYERS San Francisco Contemporary Music Brown, Olly Wilson, Michael Gordon, Players is the West Coast’s most Du Yun, Myra Melford, and Julia Wolfe. long-standing and largest new music The Contemporary Players have ensemble, comprised of twenty-two been presented by leading cultural highly skilled musicians. For 49 years, festivals and concert series including the San Francisco Contemporary Music San Francisco Performances, Los Players have created innovative and Angeles Monday Evening Concerts, Cal artistically excellent music and are one Performances, the Stern Grove Festival, Tod Brody, flute Kate Campbell, piano of the most active ensembles in the the Festival of New American Music at Kyle Bruckmann, oboe David Tanenbaum, guitar United States dedicated to contemporary CSU Sacramento, the Ojai Festival, and Sarah Rathke, oboe Hrabba Atladottir, violin music. Holding an important role in the France’s prestigious MANCA Festival. regional and national cultural landscape, The Contemporary Music Players Jeff Anderle, clarinet Susan Freier, violin the Contemporary Music Players are a nourish the creation and dissemination Peter Josheff, clarinet Roy Malan, violin 2018 awardee of the esteemed Fromm of new works through world-class Foundation Ensemble Prize, and a performances, commissions, and Adam Luftman, -

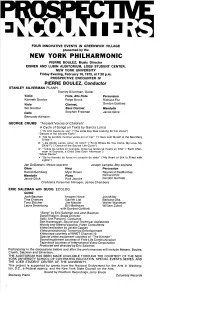

Prospective Encounters

FOUR INNOVATIVE EVENTS IN GREENWICH VILLAGE presented by the NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC PIERRE BOULEZ, Music Director EISNER AND LUBIN AUDITORIUM, LOEB STUDENT CENTER, NEW YORK UNIVERSITY Friday Evening, February 18, 1972, at 7:30 p.m. PROSPECTIVE ENCOUNTER IV PIERRE BOULEZ, Conductor STANLEY SILVERMAN PLANH Stanley Silverman, Guitar Violin Flute, Alto Flute Percussion Kenneth Gordon Paige Brook Richard Fitz Viola Clarinet, Gordon Gottlieb Sol Greitzer Bass Clarinet Mandolin Cello Stephen Freeman Jacob Glick Bernardo Altmann GEORGE CRUMB "Ancient Voices of Children" A Cycle of Songs on Texts by Garcia Lorca I "El niho busca su voz" ("The Little Boy Was Looking for his Voice") "Dances of the Ancient Earth" II "Me he perdido muchas veces por el mar" ("I Have Lost Myself in the Sea Many Times") III "6De d6nde vienes, amor, mi nino?" ("From Where Do You Come, My Love, My Child?") ("Dance of the Sacred Life-Cycle") IV "Todas ]as tardes en Granada, todas las tardes se muere un nino" ("Each After- noon in Granada, a Child Dies Each Afternoon") "Ghost Dance" V "Se ha Ilenado de luces mi coraz6n de seda" ("My Heart of Silk Is Filled with Lights") Jan DeGaetani, Mezzo-soprano Joseph Lampke, Boy soprano Oboe Harp Percussion Harold Gomberg Myor Rosen Raymond DesRoches Mandolin Piano Richard Fitz Jacob Glick PaulJacobs Gordon Gottlieb Orchestra Personnel Manager, James Chambers ERIC SALZMAN with QUOG ECOLOG QUOG Josh Bauman Imogen Howe Jon Miller Tina Chancey Garrett List Barbara Oka Tony Elitcher Jim Mandel Walter Wantman Laura Greenberg Bill Matthews -

Sfkieherd Sc~Ol Ofmusic

GUEST ARTIST RECITAL JEFFREY JACOB, Piano Thursday, September 18, 2008 8:00 p.m. Lillian H. Duncan Recital Hall sfkieherd RICE UNIVERSITY Sc~ol ofMusic PROGRAM Makrokosmos II George Crumb Twelve Fantasy-Pieces after the Zodiac (b.1929) (for amplified piano) 1. Morning Music (Genesis II) 2. The Mystic Chord 3. Rain-Death Variations 4. Twin Suns (Doppelganger aus der Ewigkeit) 5. Ghost-Nocturne: For the Druids of Stonehenge 6. Gargoyles 7. Tora I Tora I Tora I ( Cadenza Apocalittica) 8. A Prophecy of Nostradamus 9. Cosmic Wind 10. Voices from "Corona Borealis" 11. Litany of the Galactic Bells 12. Agnus Dei The reverberative acoustics of Duncan Recital Hall magnify the slightest sound made by the audience. Your care and courtesy will be appreciated. The taking ofphotographs and use ofrecording equipment are prohibited. BIOGRAPHY Described by the Warsaw Music Journal as "unquestionably one of the greatest performers of 20th-century music," and the New York Times as "an artist ofintense concentration and conviction," Jeffrey Jacob re ceived his education from the Juilliard School (Master of Music) and the Peabody Conservatory (Doctor ofMusical Arts) and counts as his prin cipal teachers Mieczyslaw Munz, Carlo Zecchi, and Leon Fleisher. Since his debut with the London Philharmonic in Royal Festival Hall, he has appeared as piano soloist with over twenty orchestras internationally including the Moscow, St. Petersburg, Seattle, Portland, Indianapolis, Charleston, Silo Paulo and Brazilian National Symphonies, and the Si lesian, Moravian , North Czech, and Royal Queenstown Philharmonics. A noted proponent ofcontemporary music, he has performed the world premieres of works written for him by George Crumb, Gunther Schuller, Vincent Persichetti, Samuel Adler, Francis Routh, and many others. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1963-1964

TANGLEWOOD Festival of Contemporary American Music August 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 1964 Sponsored by the Berkshire Music Center In Cooperation with the Fromm Music Foundation RCA Victor R£D SEAL festival of Contemporary American Composers DELLO JOIO: Fantasy and Variations/Ravel: Concerto in G Hollander/Boston Symphony Orchestra/Leinsdorf LM/LSC-2667 COPLAND: El Salon Mexico Grofe-. Grand Canyon Suite Boston Pops/ Fiedler LM-1928 COPLAND: Appalachian Spring The Tender Land Boston Symphony Orchestra/ Copland LM/LSC-240i HOVHANESS: BARBER: Mysterious Mountain Vanessa (Complete Opera) Stravinsky: Le Baiser de la Fee (Divertimento) Steber, Gedda, Elias, Mitropoulos, Chicago Symphony/Reiner Met. Opera Orch. and Chorus LM/LSC-2251 LM/LSC-6i38 FOSS: IMPROVISATION CHAMBER ENSEMBLE Studies in Improvisation Includes: Fantasy & Fugue Music for Clarinet, Percussion and Piano Variations on a Theme in Unison Quintet Encore I, II, III LM/LSC-2558 RCA Victor § © The most trusted name in sound BERKSHIRE MUSIC CENTER ERICH Leinsdorf, Director Aaron Copland, Chairman of the Faculty Richard Burgin, Associate Chairman of the Faculty Harry J. Kraut, Administrator FESTIVAL of CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN MUSIC presented in cooperation with THE FROMM MUSIC FOUNDATION Paul Fromm, President Alexander Schneider, Associate Director DEPARTMENT OF COMPOSITION Aaron Copland, Head Gunther Schuller, Acting Head Arthur Berger and Lukas Foss, Guest Teachers Paul Jacobs, Fromm Instructor in Contemporary Music Stanley Silverman and David Walker, Administrative Assistants The Berkshire Music Center is the center for advanced study in music sponsored by the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Erich Leinsdorf, Music Director Thomas D. Perry, Jr., Manager BALDWIN PIANO RCA VICTOR RECORDS — 1 PERSPECTIVES OF NEW MUSIC Participants in this year's Festival are invited to subscribe to the American journal devoted to im- portant issues of contemporary music. -

New on Naxos | September 2013

NEW ON The World’s Leading ClassicalNAXO Music LabelS SEPTEMBER 2013 © Grant Leighton This Month’s Other Highlights © 2013 Naxos Rights US, Inc. • Contact Us: [email protected] www.naxos.com • www.classicsonline.com • www.naxosmusiclibrary.com • blog.naxos.com NEW ON NAXOS | SEPTEMBER 2013 8.572996 Playing Time: 64:13 7 47313 29967 6 Johannes BRAHMS (1833–1897) Ein deutsches Requiem (A German Requiem), Op. 45 Anna Lucia Richter, soprano • Stephan Genz, baritone MDR Leipzig Radio Choir and Symphony Orchestra Marin Alsop Brahms’s A German Requiem, almost certainly triggered by the death of his mother in 1865, is one of his greatest and most popular works, quite unlike any previous Requiem. With texts taken from Luther’s translation of the Bible and an emphasis on comforting the living for their loss and on hope of the Resurrection, the work is deeply rooted in the tradition of Bach and Schütz, but is vastly different in character from the Latin Requiem of Catholic tradition with its evocation of the Day of Judgement and prayers for mercy on the souls of the dead. The success of Marin Alsop as Music Director of the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra was recognized when, in 2009, her tenure was extended to 2015. In 2012 she took up the post of Chief Conductor of the São Paulo Symphony Orchestra, where she steers the orchestra in its artistic and creative programming, recording ventures and its education and outreach activities. Marin Alsop © Grant Leighton Companion Titles 8.557428 8.557429 8.557430 8.570233 © Christiane Höhne © Peter Rigaud MDR Leipzig Radio Choir MDR Leipzig Radio Symphony Orchestra © Jessylee Anna Lucia Richter Stephan Genz 2 NEW ON NAXOS | SEPTEMBER 2013 © Victor Mangona © Victor Leonard Slatkin Sergey RACHMANINOV (1873–1943) Symphony No. -

Wehrli-Introsandtexts FINAL.Docx

Catalog of Everything and Other Stories Peter K. Wehrli Edited by Jeroen Dewulf, in cooperation with Anna Carlsson, Ann Huang, Adam Nunes and Kevin Russell eScholarship – University of California, Berkeley Department of German Published by eScholarship and Lulu.com University of California, Berkeley, Department of German 5319 Dwinelle Hall, Berkeley, CA 94720 Berkeley, USA © Peter K. Wehrli (text) © Arrigo Wittler (front cover painting Porträt Peter K. Wehrli, Forio d’Ischia 1963) © Rara Coray (back cover image) All Rights Reserved. Published 2014 Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-304-96040-5 Table of Contents Introduction 1 I. Everything is a Reaction to Dada 9 II. Robby and Alfred 26 III. Burlesque 32 IV. Hearty Home Cooking 73 V. Travelling to the Contrary of Everything 85 VI. The Conquest of Sigriswil 103 VII. Catalog of Everything I: Catalog of the 134 Most Important Observations During a Long Railway Journey 122 VIII. Catalog of Everything II: 65 Selected Numbers 164 IX. Catalog of Everything III: The Californian Catalog 189 Contributors 218 Introduction Peter K. Wehrli was born in 1939 in Zurich, Switzerland. His father, Paul Wehrli, was secretary for the Zurich Theatre and also a writer. Encouraged by his father to respect and appreciate the arts, the young Peter Wehrli enthusiastically rushed through homework assignments in order to attend as many theater performances as possible. Wehrli later studied Art History and German Studies at the universities of Zurich and Paris. As a student, he used to frequent the Café Odeon in downtown Zurich, where many famous intellectuals and artists used to meet. -

Aaron Copland: a Catalogue of the Orchestral Music

AARON COPLAND: A CATALOGUE OF THE ORCHESTRAL MUSIC 1922-25/32: Ballet “Grogh”: 30 minutes 1922-25: Dance Symphony: 18 minutes 1923: “Cortege macabre” for orchestra: 8 minutes 1923-28: Two Pieces for String Orchestra: 10 minutes 1924: Symphony for Organ and orchestra: 24 minutes 1925: Suite “Music for the Theater” for small orchestra: 21 minutes 1926: Piano Concerto: 16 minutes 1927-29/55: Symphonic Ode for orchestra: 19 minutes 1928: Symphony No.1 (revised version of Symphony for Organ) 1930/57: Orchestral Variations: 12 minutes 1931-33: Short Symphony (Symphony No.2): 15 minutes 1934/35: Ballet “Hear Ye! Hear Ye!”: 32 minutes 1934-35: “Statements” for orchestra: 18 minutes 1936: “El salon Mexico” for orchestra: 10 minutes 1937: “Prairie Journal” (“Music for Radio”) for orchestra: 11 minutes 1938: Ballet “Billy the Kid”: 32 minutes (and Ballet Suite: 22 minutes) (and extracted Waltz and Celebration for concert band: 6 minutes) 1940/41: “An Outdoor Overture” for orchestra or concert band: 10 minutes 1940: Suite “A Quiet City” for trumpet, cor anglais and strings: 10 minutes 1940/52: “John Henry” for orchestra: 4 minutes 1942: “A Lincoln Portrait” for narrator and orchestra or concert band: 15 minutes Ballet “Rodeo”: 23 minutes (and Four Dance Episodes: 19 minutes) “Fanfare for the Common Man” for brass and percussion: 2 minutes “Music for the Movies” for orchestra: 17 minutes 1942/44: “Danzon Cubano” for orchestra: 6 minutes 1943: “Song of the Guerillas” for orchestra 1944: Ballet “Appalachian Spring” for orchestra or chamber orchestra: -

A Global Sampling of Piano Music from 1978 to 2005: a Recording Project

ABSTRACT Title of dissertation: A GLOBAL SAMPLING OF PIANO MUSIC FROM 1978 TO 2005 Annalee Whitehead, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2011 Dissertation directed by: Professor Bradford Gowen Piano Division, School of Music Pianists of the twenty-first century have a wealth of repertoire at their fingertips. They busily study music from the different periods Baroque, Classical, Romantic, and some of the twentieth century trying to understand the culture and performance practice of the time and the stylistic traits of each composer so they can communicate their music effectively. Unfortunately, this leaves little time to notice the composers who are writing music today. Whether this neglect proceeds from lack of time or lack of curiosity, I feel we should be connected to music that was written in our own lifetime, when we already understand the culture and have knowledge of the different styles that preceded us. Therefore, in an attempt to promote today’s composers, I have selected piano music written during my lifetime, to show that contemporary music is effective and worthwhile and deserves as much attention as the music that preceded it. This dissertation showcases piano music composed from 1978 to 2005. A point of departure in selecting the pieces for this recording project is to represent the major genres in the piano repertoire in order to show a variety of styles, moods, lengths, and difficulties. Therefore, from these recordings, there is enough variety to successfully program a complete contemporary recital from the selected works, and there is enough variety to meet the demands of pianists with different skill levels and recital programming needs.