Biology and Ecology of Red Alder

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technical Note 37: Identification, Ecology, Use, and Culture of Sitka

TECHNICAL NOTES _____________________________________________________________________________________________ US DEPT. OF AGRICULTURE NATURAL RESOURCES CONSERVATION SERVICE Portland, OR April 2005 PLANT MATERIALS No. 37 Identification, Ecology, Use and Culture of Sitka Alder Dale C. Darris, Conservation Agronomist, Corvallis Plant Materials Center Introduction Sitka alder [Alnus viridis (Vill.) Lam. & DC. subsp. sinuata (Regel) A.& D. Löve] is a native deciduous shrub or small tree that grows to height of 20 ft, occasionally taller. Although a non-crop species, it has several characteristics useful for reclamation, forestry, and erosion control. The species is known for abundant leaf litter production, the fixation of atmospheric nitrogen in association with Frankia bacteria, and a strong fibrous root system. Where locally abundant, it naturally colonizes landslide chutes, areas of stream scour and deposition, soil slumps, and other drastic disturbances resulting in exposed minerals soils. These characteristics make Sitka alder particularly useful for streambank stabilization and soil building on impoverished sites. In addition, its low height and early slowdown in growth rate makes it potentially more desirable than red alder (Alnus rubra) to interplant with conifers such as Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menzieii) and lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta) where soil fertility is moderate to low. However, high densities can hinder forest regeneration efforts. The species may also be useful as a fast growing shrub row in field windbreaks. Sitka alder is most abundant at mid to subalpine elevations. Low elevation seed sources (below 100 m) are uncommon but probably provide the best material for reclamation and erosion control projects on valley floors and terraces. Distribution and Identification Sitka alder (Alnus viridis subsp. sinuata) is a native deciduous shrub or small tree that grows to a height of 1-6 m (3-19 ft) in the mountains and 6-12 m (19-37ft) at low elevations. -

The Prosopis Juliflora - Prosopis Pallida Complex: a Monograph

DFID DFID Natural Resources Systems Programme The Prosopis juliflora - Prosopis pallida Complex: A Monograph NM Pasiecznik With contributions from P Felker, PJC Harris, LN Harsh, G Cruz JC Tewari, K Cadoret and LJ Maldonado HDRA - the organic organisation The Prosopis juliflora - Prosopis pallida Complex: A Monograph NM Pasiecznik With contributions from P Felker, PJC Harris, LN Harsh, G Cruz JC Tewari, K Cadoret and LJ Maldonado HDRA Coventry UK 2001 organic organisation i The Prosopis juliflora - Prosopis pallida Complex: A Monograph Correct citation Pasiecznik, N.M., Felker, P., Harris, P.J.C., Harsh, L.N., Cruz, G., Tewari, J.C., Cadoret, K. and Maldonado, L.J. (2001) The Prosopis juliflora - Prosopis pallida Complex: A Monograph. HDRA, Coventry, UK. pp.172. ISBN: 0 905343 30 1 Associated publications Cadoret, K., Pasiecznik, N.M. and Harris, P.J.C. (2000) The Genus Prosopis: A Reference Database (Version 1.0): CD ROM. HDRA, Coventry, UK. ISBN 0 905343 28 X. Tewari, J.C., Harris, P.J.C, Harsh, L.N., Cadoret, K. and Pasiecznik, N.M. (2000) Managing Prosopis juliflora (Vilayati babul): A Technical Manual. CAZRI, Jodhpur, India and HDRA, Coventry, UK. 96p. ISBN 0 905343 27 1. This publication is an output from a research project funded by the United Kingdom Department for International Development (DFID) for the benefit of developing countries. The views expressed are not necessarily those of DFID. (R7295) Forestry Research Programme. Copies of this, and associated publications are available free to people and organisations in countries eligible for UK aid, and at cost price to others. Copyright restrictions exist on the reproduction of all or part of the monograph. -

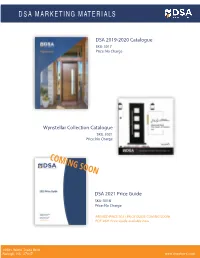

Marketing Brochure (Updated 2021)

DSA MARKETING MATE RI ALS DSA 2019-2020 Catalogue SKU: 3017 Price: No Charge Wynstellar Collection Catalogue SKU: 3021 Price: No Charge DSA 2021 Price Guide SKU: 3018 Price: No Charge PRINTED PRICE 2021 PRICE GUIDE COMING SOON! PDF 2021 Price Guide available now Stain Sample Keyring SKU: /DSA STAIN SAMP Price: No Charge 2-1/4” X 4” Stain Samples Finishes: Coco, Russet, Chestnut Wood Species: Mahogany & Knotty Alder 6 total stain samples Wynstellar Sample Keyring SKU: /DSA STAIN SAMP Price: No Charge 3” X 4” Stain Samples Finishes: Ebony & CInnamon Bark Wood Species: Accoya 2 total stain samples Glass Sample SKU: GLASS SAMPLE Price: $20.00 Shipping Cost: $15.00 Ships Via: UPS 3” X 3” Panes Overall Size: 13” X 6-3/4” Glass Types: Rain, Flemish, Clear Beveled, Sandblasted, Gluechip, Grain IG Low E, White Laminated, and Fluted IG Low E Miniature Wynstellar Bi Fold Door SKU: 3037-FD Price: $900.00 Crating Cost: $100.00 Shipping Cost: $175.00 ShipsVia: Averrit *can be shipped with existing order to avoid seperate S&H - crating still applies 13” X 27” Door Panels Dual-Finished : Ebony & Primed (back) Timber: Accoya Clear Ig Low E Glass Overall Size: 48” X 36” Mahogany Pre-Hung Sample SKU: 3006 Price: $100 Shipping Cost: $50 Ships Via: UPS 17-3/4” X 19-1/2” Frame Size Timber: Mahoghany Knotty Alder Pre-Hung Sample SKU: 3006 Price: $100 Shipping Cost: $50 Ships Via: UPS 17-3/4” X 19-1/2” Frame Size Timber: Knotty Alder Mahogany Corner Cut Samples SKU: 3001 Price: $40 Shipping Cost: $30 Ships Via: UPS 12” X 12” Sample Timber: Mahogany Coco, Russet, -

A Case Study on the Potential of the Multipurpose Prosopis Tree

23 Underutilised crops for famine and poverty alleviation: a case study on the potential of the multipurpose Prosopis tree N.M. Pasiecznik, S.K. Choge, A.B. Rosenfeld and P.J.C. Harris In its native Latin America, the Prosopis tree (also known as Mesquite) has multiple uses as a fuel wood, timber, charcoal, animal fodder and human food. It is also highly drought-resistant, growing under conditions where little else will survive. For this reason, it has been introduced as a pioneer species into the drylands of Africa and Asia over the last two centuries as a means of reclaiming desert lands. However, the knowledge of its uses was not transferred with it, and left in an unmanaged state it has developed into a highly invasive species, where it encroaches on farm land as an impenetrable, thorny thicket. Attempts to eradicate it are proving costly and largely unsuccessful. In 2006, the problem of Prosopis was hitting the headlines on an almost weekly basis in Kenya. Yet amidst calls for its eradication, a pioneering team from the Kenya Forestry Research Institute (KEFRI) and HDRA’s International Programme set out to demonstrate its positive uses. Through a pilot training and capacity building programme in two villages in Baringo District, people living with this tree learned for the first time how to manage and use it to their benefit, both for food security and income generation. Results showed that the pods, milled to flour, would provide a crucial, nutritious food supplement in these famine-prone desert margins. The pods were also used or sold as animal fodder, with the first international order coming from South Africa by the end of the year. -

TREES HAVE HIGHER LONGITUDINAL GROWTH STRAINS in THEIR STEMS THAN in THEIR ROOTS in the Secondary Xylem of Trees, Each Wood Cell

a3q14 Int. 1. Plant Sci. 158(4):418-423. 1997. © 1997 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. 1058-5893/97/5804-0003$03.00 TREES HAVE HIGHER LONGITUDINAL GROWTH STRAINS IN THEIR STEMS THAN IN THEIR ROOTS BARBARA L. GARTNER Department of Forest Products, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon 97 33 1-7402 Longitudinal growth strains develop in woody tissues during cell-wall formation. This study compares stems, which have a mechanical role and experience longitudinal stresses, and nonstructural roots, which have little mechanical role and experience few or no longitudinal stresses, to test the hypothesis that growth strains are produced in stems of straight trees as an adaptive feature for mechanical loads. I measured growth strains in one stem (at breast height) and one nonstructural root (beyond the zone of rapid taper and/or beyond a major change in root direction) for 13-15 individuals of each of four tree species, Pseudotsuga menziesii, Thuja heterophylla, Acer macrophyllum, and Alnus rubra. Forty-seven of the 54 individuals had higher strains in their stems than in their roots (4.3 ± 0.3 x 10- 4 and 1.5 ± 0.3 x 10-4, respectively). Growth strain was two to five times higher for stems than roots. The modulus of elasticity (MOE) in bending was also higher in stem tissues (from literature values) than in root tissue (from this study). Calculated growth stresses, the product of growth strain and MOE, averaged 6-11 times higher in stems than roots for the four species. The higher strain and stress in stems than roots indicate that the strains and stresses are adaptive features that are produced in response to, or in "anticipation," of mechanical loads. -

Nitrogen Transformations in Soils Beneath Red Alder and Conifers

From Biology of Alder ERTY OF: Proceedings of Northwest Scientific Association Annual Mee t4■::::),...;ADE HEAD EXPERIMENTAL FOREST April 14-15, 1967 Published 1968 AND SCENIC RESEARCH AREA OTIS, OREGON Nitrogen transformations in soils beneath red alder and conifers W. B. Bollen, Abstract Oregon State University Corvallis, Oregon Transformations of nitrogen in organic matter in the soil are essential to and plant nutrition because nitrogen in the form of proteins and other organic K. C. Lu compounds is not directly available. These compounds must undergo Forestry Sciences Laboratory microbial decomposition to liberate nitrogen as ammonium (NH -I-4) and Pacific Northwest Forest nitrate (NO3 ), which can then be absorbed by plant roots. and Range Experiment Station Nitrogen transformations, particularly nitrification, are rapid in soils under Corvallis, Oregon coastal Oregon stands of red alder (Alnus rubra Bong.); conifers — Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirb.) Franco), western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla Raf) Sarg.), and Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis (Bong.) Carr.); and mixed stands of alder and conifers. Nitrification is especially rapid in the F layer beneath alder stands despite a very low pH. These findings are from a study of contributions to the nitrogen economy by red alder conducted at Cascade Head Experimental Forest near Otis, Oregon (Chen, 1965). 1 Procedures Ammonifying capacity of the different samples was compared by testing duplicate 50-g portions, ovendry basis, of each with peptone equivalent to 1,000 ppm nitrogen. These samples, and samples of untreated soil, were incubated for 35 days at 28 C. Moisture was adjusted to 50 percent of the water- holding capacity. At the close of incubation, each sample was analyzed for NH+4, NO-2, and NO-3 nitrogen and for pH. -

COMÚN INGLÉS COMÚN ESPAÑOL NOMBRE CIENTÍFICO Alder Aliso

COMÚN INGLÉS COMÚN ESPAÑOL NOMBRE CIENTÍFICO Alder Aliso Alnus spp. Alligator juniper Tascate Juniperus deppeana Almond Almendro Prunus dulcis Anaqua Manzanillo Ehretia anacua Apricot Albaricoquero Prunus armeniaca Ash Fresno, plumero Fraxinus spp. Ashe juniper Sabino Juniperus ashei Basswood Tilo Tilia spp. Ball moss Gallitos Tillandsia recurvata Beech Haya Fagus spp. Birch Abedul Betula spp. Black cherry Cerezo Prunus serotina Black locust Algarrobo Robinia pseudoacacia Boxelder Negundo Acer negundo Buckeye Castaño de Indias Aesculus spp. Buckthorn Rhamnus Rhamnus spp. Bumelia Coma Bumelia spp. Catalpa Catalpa Catalpa spp. Catclaw acacia Uña de gato Acacia greggii Cedar Cedro Cedrus spp. Chestnut Castaño Castanea spp. Chinaberry Canelo, lila de China, paraiso, jaboncillo Melia azedarach Common apple Manzano Malus x domestica Common edible fig Higo Ficus carica Common olive Olivo Olea europaea Cottonwood/aspen Álamo/ álamo temblón Populus spp. Crape myrtle Crespón, reina de las flores Langerstroemia spp. Cypress Ciprés Cupressus spp. Desert willow Flor de mimbre Chilopsis linearis Dogwood Cornejo Cornus spp. Eastern red cedar Cedro rojo, enebro Juniperus virginiana Ebony Ébano Diospyros spp. Elm Olmo Ulmus spp. Eucalyptus Eucalipto Eucalyptus spp. Evergreen sumac Lantrisco, lentisco Rhus sempervirens Filbert nut tree Avellano Corylus avellana Fir Abeto Abies spp. Ginkgo, maidenhair Gingo Ginkgo biloba Grape Parra, uva Vitis spp. Hackberry Palo blanco Celtis spp. Hemlock Cicuta Tsuga spp. Hickory Nogal americano Carya spp. Holly Acebo Ilex spp. Juniper Enebro Juniperus spp. Larch Alerce Larix spp. Leadtree Tepeguaje Leucaena spp. Live oak Encino, tesmoli, texmol Quercus virginiana Loquat Níspero Eriobotrya japonica Madrone Madroño Arbutus spp. Magnolia Palo de cacique, magnolio Magnolia grandiflora Mahogany Caoba Swietenia spp. -

Alder Canopy Dieback and Damage in Western Oregon Riparian Ecosystems

Alder Canopy Dieback and Damage in Western Oregon Riparian Ecosystems Sims, L., Goheen, E., Kanaskie, A., & Hansen, E. (2015). Alder canopy dieback and damage in western Oregon riparian ecosystems. Northwest Science, 89(1), 34-46. doi:10.3955/046.089.0103 10.3955/046.089.0103 Northwest Scientific Association Version of Record http://cdss.library.oregonstate.edu/sa-termsofuse Laura Sims,1, 2 Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, Oregon State University, 1085 Cordley Hall, Corvallis, Oregon 97331 Ellen Goheen, USDA Forest Service, J. Herbert Stone Nursery, Central Point, Oregon 97502 Alan Kanaskie, Oregon Department of Forestry, 2600 State Street, Salem, Oregon 97310 and Everett Hansen, Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, 1085 Cordley Hall, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon 97331 Alder Canopy Dieback and Damage in Western Oregon Riparian Ecosystems Abstract We gathered baseline data to assess alder tree damage in western Oregon riparian ecosystems. We sought to determine if Phytophthora-type cankers found in Europe or the pathogen Phytophthora alni subsp. alni, which represent a major threat to alder forests in the Pacific Northwest, were present in the study area. Damage was evaluated in 88 transects; information was recorded on damage type (pathogen, insect or wound) and damage location. We evaluated 1445 red alder (Alnus rubra), 682 white alder (Alnus rhombifolia) and 181 thinleaf alder (Alnus incana spp. tenuifolia) trees. We tested the correlation between canopy dieback and canker symptoms because canopy dieback is an important symptom of Phytophthora disease of alder in Europe. We calculated the odds that alder canopy dieback was associated with Phytophthora-type cankers or other biotic cankers. -

RED ALDER Northwest Extracted a Red Dye from the Inner Bark, Which Was Used to Dye Fishnets

Plant Guide and hair. The native Americans of the Pacific RED ALDER Northwest extracted a red dye from the inner bark, which was used to dye fishnets. Oregon tribes used Alnus rubra Bong. the innerbark to make a reddish-brown dye for basket Plant Symbol = ALRU2 decorations (Murphey 1959). Yellow dye made from red alder catkins was used to color quills. Contributed by: USDA NRCS National Plant Data Center A mixture of red alder sap and charcoal was used by the Cree and Woodland tribes for sealing seams in canoes and as a softener for bending boards for toboggans (Moerman 1998). Wood and fiber: Red alder wood is used in the production of wooden products such as food dishes, furniture, sashes, doors, millwork, cabinets, paneling and brush handles. It is also used in fiber-based products such as tissue and writing paper. In Washington and Oregon, it was largely used for smoking salmon. The Indians of Alaska used the hallowed trunks for canoes (Sargent 1933). Medicinal: The North American Indians used the bark to treat many complaints such a headaches, rheumatic pains, internal injuries, and diarrhea (Moerman 1998). The Salinan used an extract of the bark of alder trees to treat cholera, stomach cramps, and stomachaches (Heinsen 1972). The extract was made with 20 parts water to 1 part fresh or aged bark. The bark contains salicin, a chemical similar to aspirin (Uchytil 1989). Infusions made from the bark of red alders were taken to treat anemia, colds, congestion, and to © Tony Morosco relieve pain. Bark infusions were taken as a laxative @ CalFlora and to regulate menstruation. -

Alder Alnus Glutinosa Fearnóg Alder Is a Native Deciduous Tree Species Which Is Often Found Growing Along Banks of Streams and Rivers and in Low-Lying Swampy Land

Trees Alder Alnus glutinosa Fearnóg Alder is a native deciduous tree species which is often found growing along banks of streams and rivers and in low-lying swampy land. It is a water-loving tree reaching heights of 21m (70ft). During spring, four stages of production can be seen on an alder at any given time: the old cones of last years fruiting, the new leaf-buds or leaves and the male and female catkins of this year. Alder is our only broadleaved tree to produce cones. It matures at around 30 years of age and is then capable of a full crop of seeds. Alder leaves are held out horizontally. They are rounded and of an inverted heart-shape, with the broadest part furthest from the stem. When young they are somewhat sticky, as a gum is produced by the tree to ward off moisture. Alder catkins form in the autumn preceding their flowering. They remain dormant on the tree throughout winter and open in the spring before the leaves. The female catkins have threads hanging from them which catch the pollen from the developed male catkins, after which they grow larger and become dark reddish-brown as the seeds develop within. The ripe seeds fall in October and November. They have airtight cavities in their walls which allow them to float on water, along with a coating of oil to preserve them. Alder wood resists decay when in water and has traditionally been used to make boats, canal lockgates, bridges, platforms and jetties. Out of the water alder wood is soft and splits easily. -

California Forest Insect and Disease Training Manual

California Forest Insect and Disease Training Manual This document was created by US Forest Service, Region 5, Forest Health Protection and the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, Forest Pest Management forest health specialists. The following publications and references were used for guidance and supplemental text: Forest Insect and Disease Identification and Management (training manual). North Dakota Forest Service, US Forest Service, Region 1, Forest Health Protection, Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation and Idaho Department of Lands. Forest Insects and Diseases, Natural Resources Institute. US Forest Service, Region 6, Forest Health Protection. Forest Insect and Disease Leaflets. USDA Forest Service Furniss, R.L., and Carolin, V.M. 1977. Western forest insects. USDA Forest Service Miscellaneous Publication 1339. 654 p. Goheen, E.M. and E.A. Willhite. 2006. Field Guide to Common Disease and Insect Pests of Oregon and Washington Conifers. R6-NR-FID-PR-01-06. Portland, OR. USDA Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Region. 327 p. M.L. Fairweather, McMillin, J., Rogers, T., Conklin, D. and B Fitzgibbon. 2006. Field Guide to Insects and Diseases of Arizona and New Mexico. USDA Forest Service. MB-R3-16-3. Pest Alerts. USDA Forest Service. Scharpf, R. F., tech coord. 1993. Diseases of Pacific Coast Conifers. USDA For. Serv. Ag. Hndbk. 521. 199 p.32, 58. Tree Notes Series. California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection. Wood, D.L., T.W. Koerber, R.F. Scharpf and A.J. Storer, Pests of the Native California Conifers, California Natural History Series, University of California Press, 2003. Cover Photo: Don Owen. 1978. Yosemite Valley. -

First-Year Progress Report

Progress Report 1 October 2001 – 31 March 2004 CHEMICAL ECOLOGY AND MANAGEMENT OF FOREST INSECTS NSERC COOPERATIVE RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT GRANT No. CRDPJ247613-01, and BC FORESTRY INNOVATION INVESTMENT GRANT NO. R04-055 with matching contributions from the following industrial sponsors: Abitibi Consolidated Inc., B.C. Hydro and Power Authority, Bugbusters Pest Management Inc., Canadian Forest Products Ltd., Gorman Bros. Ltd., International Forest Products Ltd., Lignum Ltd., Manning Diversified Forest Products Ltd., Millar-Western Forest Products Ltd., Phero Tech Inc., Riverside Forest Products Ltd., Slocan Forest Products Ltd., Tembec Forest Industries Ltd., TimberWest Forest Ltd., Tolko Industries Ltd., Weldwood of Canada Ltd., West Fraser Mills Ltd., Western Forest Products Ltd., and Weyerhaeuser Canada Ltd. by John H. Borden, RPF, RPBio, FRSC Professor Emeritus, Department of Biological Sciences Simon Fraser University Burnaby, B.C. V5A 1S6 1 April 2004 Executive Summary This project was originally intended for a two-year duration, beginning on 1 October 2001. It was supported by mainly by an NSERC Cooperative Research and Development Grant for $250,000 which matched equal contributions from the forest industry (19 companies collectively), and B.C. government agencies, Forest Renewal B.C. and its successor, Forestry Innovation Investment (FII). Because of delays in renewed funding by FII in the second year, the NSERC funding was extended for six months, so that the end dates of both the NSERC and FII grants were on 31 March 2004. The research on forest insects supported by this funding had three objectives: 1. to make fundamental discoveries based on rigorous experiments; 2. to identify those discoveries that have practical potential in forest pest management; and 3.