Predictive Limnology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecological Impact Assessment in the Context of EIA

RADAR Research Archive and Digital Asset Repository An evaluation of ecological impact assessment in England Katherine Drayson (2012) https://radar.brookes.ac.uk/radar/items/0d813ad8-3f82-48f2-a25d-f04f78444cca/1/ Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, the full bibliographic details must be given as follows: Drayson, K (2012) An evaluation of ecological impact assessment in England PhD, Oxford Brookes University Removed pp. 258-end: published papers WWW.BROOKES.AC.UK/GO/RADAR AN EVALUATION OF ECOLOGICAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT IN ENGLAND Katherine Drayson A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the award of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Oxford Brookes University DECEMBER 2012 ABSTRACT Ecological impact assessment (EcIA) has historically been poorly performed, resulting in poor quality EcIA chapters. No research has been conducted to identify whether poor quality EcIA chapters result in poor quality mitigation and therefore potential net loss of biodiversity. A review of 112 EcIA chapters was conducted to determine whether there have been improvements since the last review in 2000 and which factors are linked with EcIA chapter quality, such as the introduction of professional guidance in 2006. -

Determination in an Androdioecious Population of Mercurialls Annua

Heredity 78 (1997) 50—56 Received 19 January 1996 Mixed genetic and environmental sex determination in an androdioecious population of Mercurialls annua JOHN PANNELL* Department of P/ant Sciences, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3R8, U.K. Mercurialisannua is a ruderal of pan-European distribution. In southern Spain, southern Portugal and northern Morocco, males coexist with monoecious (cosex) individuals at frequen- cies which vary between zero and about 30 per cent. Here, I report the results of two glasshouse experiments which aimed to characterize the mode of sex determination in one such androdioecious population. In a breeding experiment, cosexes isolated from males produced only cosexual progeny, whereas those allowed to mate with males produced both cosexual and male offspring. The results are consistent with a single-locus model of sex inheritance, with maleness determined by a dominant allele. In a density experiment, the frequency of males correlated positively with density, confirming field observations. Differential mortality or germination between the sexes was excluded by experimental design, so that the result supports the hypothesis of density-dependent gender choice. A negative correlation between density and the proportion of 'late cosexes' (males which turned cosexual late in their development), and the lack of any differences in the proportion of pure (unchanged) cosexes between density, suggest that only males were capable of sex change. This interpretation is consistent with the results of the breeding experiment, in which late cosexes occurred only in the offspring of cosexes allowed to mate with males. I argue that these findings help to explain the maintenance of androdioecy in M annua. -

An Exploration of the Three Major Schools of Taxonomy Using Science Fiction Examples

AN EXPLORATION OF THE THREE MAJOR SCHOOLS OF TAXONOMY USING SCIENCE FICTION EXAMPLES A thesis submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Masters of Arts By Jessica Gentry Read December, 2009 Thesis written by Jessica Gentry Read B.A., Washington and Jefferson College, 1998 M.A., Kent State University, 2009 Approved by ________Deborah Barnbaum___________, Advisor ________David W. Odell-Scott_________, Chair, Department of Philosophy _______Timothy Moerland____________, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences ii Table of Contents Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………..iv Introduction………………………………………………………………………...1 Chapter 1. Definitions and Explanations of Terms………………………………...4 Definition of Taxonomy and Related Terms………………………4 Virtues of a School of Taxonomy………………………………...10 Definition of Species……………………………………………...17 Definition of Character……………………………………………30 Definition of Grouping and Ranking……………………………...37 2. Evolutionary Taxonomy……………………………………………….39 Goals and Tenets of Evolutionary Taxonomy…………………….40 3. Cladism………………………………………………………………...54 Goals and Tenets of Cladism……………………………………...54 Advantages and Disadvantages of Cladism……………………….71 4. Pheneticism…………………………………………………………….73 Goals and Tenets of Pheneticism………………………………….74 Pheneticism and Aristotle………………………………………….81 Advantages and Disadvantages of Pheneticism…………………....84 5. Testing the Schools of Taxonomy Using Science Fiction……………....90 Science Fiction and its Purpose…………………………………….92 Eugenically Developed Humans…………………………………..100 -

Sara Lil Middleton

Sara Lil Middleton Address: St Cross College, 61 St Giles', Oxford OX1 3LZ Email: [email protected] Twitter: @sara_lil_plants Orcid: 0000-0001-5307-8029 EDUCATION DPhil in Environmental Research, St Cross College, University of Oxford (2018-present) A four-year DPhil programme funded by the NERC-Oxford DTP in Environmental Research. MRes Ecosystems & Environmental Change (Distinction 78%), Imperial College London (2016-2017) MRes course with ten weeks of modules, including Ecology and Global Change, Science and Policy, Biodiversity and Geographical Information Systems, followed by a nine-month research project and science communication/policy written coursework based on the research project. Bsc Environmental Sciences (First Class Honours 78%), Oxford Brookes University (2012-2015) I undertook a wide range of modules, including: Advanced Topics in Wildlife Conservation, Plant Science, Threatened Species, Environmental Processes, Pollution and Climate Change, Environmental Change: Fieldwork and Research. Lab work: Sediment analysis (particle size analysis, magnetic susceptibility, pH/conductivity) chemical titrations; flower and pollen analyses (SEM and optical microscope). Fieldwork: Plant and insect identification, Phase 1 and 2 surveying, quadrat sampling, freshwater and terrestrial invertebrates in Oxfordshire; Devon; Cevennes National Park, France. RESEARCH EXPERIENCE DPhil Project (January 2019 – present) Supervised by Dr Rob Salguero-Gómez and Prof Andy Hector “Using functional traits and demography to address global change challenges of climate change, tropical deforestation and invasive alien species”. Methods: climate manipulation, plant identification, systematic mapping and multivariate analysis. Analysis: R, Python, Image J Plant Diversity in Banana Production Systems (February – March 2018) Measuring herbaceous plant species diversity in different banana production systems in Costa Rica. -

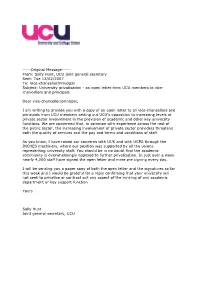

Tue 13/02/2007 To: Vice-Chancellor/Principal Subject: University Privatisation - an Open Letter from UCU Members to Vice- Chancellors and Principals

-----Original Message----- From: Sally Hunt, UCU joint general secretary Sent: Tue 13/02/2007 To: Vice-chancellor/Principal Subject: University privatisation - an open letter from UCU members to vice- chancellors and principals Dear vice-chancellor/principal, I am writing to provide you with a copy of an open letter to all vice-chancellors and principals from UCU members setting out UCU's opposition to increasing levels of private sector involvement in the provision of academic and other key university functions. We are concerned that, in common with experience across the rest of the public sector, the increasing involvement of private sector providers threatens both the quality of services and the pay and terms and conditions of staff. As you know, I have raised our concerns with UUK and with UCEA through the JNCHES machinery, where our position was supported by all the unions representing university staff. You should be in no doubt that the academic community is overwhelmingly opposed to further privatisation. In just over a week nearly 4,500 staff have signed the open letter and more are signing every day. I will be sending you a paper copy of both the open letter and the signatures so far this week and I would be grateful for a reply confirming that your university will not seek to privatise or contract out any aspect of the running of any academic department or key support function Yours Sally Hunt Joint general secretary, UCU An open letter to vice-chancellors and principals from UCU members We are writing to you to let you know of UCU's opposition to increasing levels of private sector involvement in the provision of academic and other key university functions. -

Jill Bailey the Facts on File Dictionary of Botany

The Facts On File DICTIONARY of BOTANY The Facts On File DICTIONARY of BOTANY Edited by Jill Bailey The Facts On File Dictionary of Botany Copyright © 2003 by Market House Books Ltd All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Checkmark Books An imprint of Facts On File, Inc. 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Facts on File dictionary of botany / edited by Jill Bailey. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ). ISBN 0-8160-4910-6 (hc)—ISBN 0-8160-4911-4 (pbk.) 1. Botany—Dictionaries. I. Title: Dictionary of botany. II. Bailey, Jill. III. Facts on File, Inc. QK9.F33 2002 580'.3—dc2l 2002035202 Checkmark Books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Compiled and typeset by Market House Books Ltd, Aylesbury, UK Printed in the United States of America MP 10987654321 This book is printed on acid-free paper PREFACE This dictionary is one of a series covering the terminology and concepts used in important branches of science. The Facts On File Dictionary of Botany is planned as an additional source of information for students taking Ad- vanced Placement (AP) Science courses in high schools, but will also be help- ful to older students taking introductory college courses. -

Faculty and Research Update

FACULTY AND RESEARCH UPDATE Faculty of Health & Life Sciences March 2018 Contents FACULTY AND RESEARCH UPDATE Faculty of Health & Life Sciences March 2018 3 12 15 19 2018 HLS Postgraduate Research Symposium 3 4 10 Years of Science Bazaar at Oxford Brookes 4 Curiosity Carnival 6 Welcome to the March 2018 edition OxINMAHR 7 of our HLS Faculty and Research Sugar Awareness Week 8 Update! It has been an incredibly rewarding issue to The Infant Feeding Network 9 work on, especially thanks to all who have Midwifery Conference 10 submitted articles on our core themes of innovation, industry, and interdisciplinary Tim Shreeve’s Professorial Lecture 10 collaboration – the response has in fact The Engage 2017 Conference 11 been so enthusiastic that this edition has grown to almost double the size of our Antibiotics Unearthed 12 usual Newsletters! It is full of illustrative, Introducing the Faculty Innovation Team 13 informative, and also inspirational articles, a fascinating panoply of the diverse research Knowledge Transfer Partnerships: An Introduction 14 projects, PPI events, knowledge transfer iCASE PhD Studentships 15 and public engagement events, industry collaborations, international networks, and Bio to Business 16 efforts to enhance the student experience Brookes Psychologists Working with Commercial that are so characteristic of HLS! Test Publishers 18 Our focus here, and of course in the years PhDs Awarded in HLS 18 to come, is on ideas and projects that reach out beyond the confines of individual The New Clinical Skills and Simulation Suites disciplines to explore new conceptual at Marston Road 19 approaches and commercial opportunities. We need to make the most of routes to Celebrating Our New Research Facilities bridge academic specialisms and foster in the Sinclair Annex 20 enterprise projects grounded in the wider Working Towards Athena Swan ‘Silver’ 21 economy and health industry landscape. -

OXFORD BROOKES UNIVERSITY RESOLUTION of PARAPHYLY in CAESALPINIOID LEGUMES RUTH P. CLARK a Thesis in Partial Fulfilment of the R

OXFORD BROOKES UNIVERSITY RESOLUTION OF PARAPHYLY IN CAESALPINIOID LEGUMES RUTH P. CLARK A thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Oxford Brookes University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy on the basis of published work Submitted December 2017 Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................................ 3 ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................................. 6 WORD COUNT .................................................................................................................................. 8 1.1 BACKGROUND AND LITERATURE REVIEW ............................................................... 9 1.2 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 9 1.3 A history of systems of biological classification ............................................................... 11 1.4 Concepts and methods in taxonomy .................................................................................. 15 1.5 Taxonomy of the Caesalpinioideae (sensu traditional) ...................................................... 26 1.6 Taxonomy of the Cercidoideae ......................................................................................... 27 1.6.1 Taxonomy of Bauhinia sensu lato .............................................................................. 29 1.6.2 Segregates