'' on Tranzlaytin Howmer '': the Iliad in Birmingham Hexameters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Essay 2 Sample Responses

Classics / WAGS 23: Second Essay Responses Grading: I replaced names with a two-letter code (A or B followed by another letter) so that I could read the essays anonymously. I grouped essays by levels of success and cross-read those groups to check that the rankings were consistent. Comments on the assignment: Writers found all manner of things to focus on: Night, crying, hospitality, the return of princes from the dead (Hector, Odysseus), and the exchange of bodies (Hector, Penelope). Here are four interesting and quite different responses: Essay #1: Substitution I Am That I Am: The Nature of Identity in the Iliad and the Odyssey The last book of the Iliad, and the penultimate book of the Odyssey, both deal with the issue of substitution; specifically, of accepting a substitute for a lost loved one. Priam and Achilles become substitutes for each others' absent father and dead son. In contrast, Odysseus's journey is fraught with instances of him refusing to take a substitute for Penelope, and in the end Penelope makes the ultimate verification that Odysseus is not one of the many substitutes that she has been offered over the years. In their contrasting depictions of substitution, the endings of the Iliad and the Odyssey offer insights into each epic's depiction of identity in general. Questions of identity are in the foreground throughout much of the Iliad; one need only try to unravel the symbolism and consequences of Patroclus’ donning Achilles' armor to see how this is so. In the interaction between Achilles and Priam, however, they are particularly poignant. -

Homer and Greek Epic

HomerHomer andand GreekGreek EpicEpic INTRODUCTION TO HOMERIC EPIC (CHAPTER 4.IV) • The Iliad, Books 23-24 • Overview of The Iliad, Books 23-24 • Analysis of Book 24: The Death-Journey of Priam •Grammar 4: Review of Parts of Speech: Nouns, Verbs, Adjectives, Adverbs, Pronouns, Prepositions and Conjunctions HomerHomer andand GreekGreek EpicEpic INTRODUCTION TO HOMERIC EPIC (CHAPTER 4.IV) Overview of The Iliad, Book 23 • Achilles holds funeral games in honor of Patroclus • these games serve to reunite the Greeks and restore their sense of camaraderie • but the Greeks and Trojans are still at odds • Achilles still refuses to return Hector’s corpse to his family HomerHomer andand GreekGreek EpicEpic INTRODUCTION TO HOMERIC EPIC (CHAPTER 4.IV) Overview of The Iliad, Book 24 • Achilles’ anger is as yet unresolved • the gods decide he must return Hector’s body • Zeus sends Thetis to tell him to inform him of their decision • she finds Achilles sulking in his tent and he agrees to accept ransom for Hector’s body HomerHomer andand GreekGreek EpicEpic INTRODUCTION TO HOMERIC EPIC (CHAPTER 4.IV) Overview of The Iliad, Book 24 • the gods also send a messenger to Priam and tell him to take many expensive goods to Achilles as a ransom for Hector’s body • he sneaks into the Greek camp and meets with Achilles • Achilles accepts Priam’s offer of ransom and gives him Hector’s body HomerHomer andand GreekGreek EpicEpic INTRODUCTION TO HOMERIC EPIC (CHAPTER 4.IV) Overview of The Iliad, Book 24 • Achilles and Priam arrange an eleven-day moratorium on fighting -

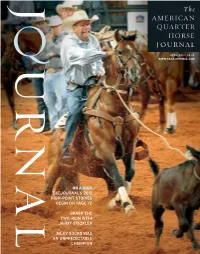

The American ≤Uarter Horse Journal That You Can’T Get Anywhere Else Are the Breeding, Halter and Performance Statistics That We Mine from A≤HA’S Database

J J J J The AMERICAN ≤UARTER HORSE J OURNAL APRIL 2013 • $4.25 WWW.AQHAJOURNAL.COM U ≤≤U R R N N A A ON A HIGH THE JOURNAL’S 2012 HIGH-POINT STORIES BEGIN ON PAGE 72 GRASP THE TWO-REIN WITH L L JIMMY STICKLER SILKY SOCKS WAS AN UNPREDICTABLE CHAMPION CONTENTS FEATURES FEATURES 18 Structure in Detail 58 Hard To Get Playboy By Christine Hamilton By Jennifer K. Hancock The hind limb – looking at the stifle This Bank of America high-point senior horse has an all-around great personality 24 Borrow a Trainer By AQHA Professional Horseman 62 A≤HA’s 2012 Michael Colvin with Christine Hamilton High-Point Winners Lengthening stride at any gait 64 Making Runners 28 Barn Babies By Richard Chamberlain Breeders share their 2013 arrivals. Follow along with 2-year-olds on the track. Part of a continuing series 32 Grasping the Two-Rein By Annie Lambert 68 Ricky Ramirez Symbiosis of the mecate and bridle reins has By Honi Roberts enhanced training since the vaqueros developed This young jockey is going places – fast. it into an art form. 38 The Unpredictable 78 Foundation Donors Champion By Larri Jo Starkey April 2013 Silky Socks spooked on a dime, but he The official publication had a world championship ride in him. of the American Quarter 44 60 Years Ago These two are Horse Association. AQHA’s first high-point award winners all-around About the Cover 46 characters. 2012 AQHA All-Around 46 Kaleena Weakly and Senior Horse Hard To Get Playboy Hours Yours And Mine By Jennifer K. -

The General Stud Book : Containing Pedigrees of Race Horses, &C

^--v ''*4# ^^^j^ r- "^. Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2009 witii funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/generalstudbookc02fair THE GENERAL STUD BOOK VOL. II. : THE deiterol STUD BOOK, CONTAINING PEDIGREES OF RACE HORSES, &C. &-C. From the earliest Accounts to the Year 1831. inclusice. ITS FOUR VOLUMES. VOL. II. Brussels PRINTED FOR MELINE, CANS A.ND C"., EOILEVARD DE WATERLOO, Zi. M DCCC XXXIX. MR V. un:ve PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION. To assist in the detection of spurious and the correction of inaccu- rate pedigrees, is one of the purposes of the present publication, in which respect the first Volume has been of acknowledged utility. The two together, it is hoped, will form a comprehensive and tole- rably correct Register of Pedigrees. It will be observed that some of the Mares which appeared in the last Supplement (whereof this is a republication and continua- tion) stand as they did there, i. e. without any additions to their produce since 1813 or 1814. — It has been ascertained that several of them were about that time sold by public auction, and as all attempts to trace them have failed, the probability is that they have either been converted to some other use, or been sent abroad. If any proof were wanting of the superiority of the English breed of horses over that of every other country, it might be found in the avidity with which they are sought by Foreigners. The exportation of them to Russia, France, Germany, etc. for the last five years has been so considerable, as to render it an object of some importance in a commercial point of view. -

The Father-Son Relationship in the Iliad: the Case of Priam- Hector Introduction

Tsoutsouki, C. (2014); The Father-Son Relationship in the Iliad: The Case of Priam- Hector Introduction Rosetta 16: 78 – 92 http://www.rosetta.bham.ac.uk/issue16/tsoutsouki.pdf The Father-Son Relationship in the Iliad: The Case of Priam-Hector Introduction Christiana Tsoutsouki It is widely accepted that the Iliad is not merely a tale of the Trojan War and its battles, but also a literary product that yields interesting insights into the nature of human interactions. Arguably, one of the most prominent expressions of these interactions is the father-son relationship, through which the epic narrative keeps constantly at the background the existence of a world beyond the battlefield, where fathers and sons engage in a tense and intimate interaction characterised by mutual feelings of love, affection, concern, and, most importantly, interdependency. The significance of the Iliadic father-son relationship has already been noted by a number of scholars. Greene (1970) was the first to draw attention to this topic by aptly characterising the Iliad as ‘a great poem of fatherhood’, and a few years later Lacey observed ‘how completely family-centred the society of Homeric poems is’ (1968: 34). Likewise, Redfield (1975), and Finlay (1980) examined the prevalence of the father- son bond in the epic narrative, while Griffin (1980) focused on the theme of the bereaved parents. Crotty (1994) dealt with different epic pairs of fathers and sons, being particularly concerned with the standards that the former impose on the latter. Interestingly, Ingalls (1998) centred on the attitudes towards children in the epic and argued for their high value in the Homeric society. -

On Translating Homer's Iliad

On Translating Homer’s Iliad Caroline Alexander Abstract: This reflective essay explores the considerations facing a translator of Homer’s work; in par- ticular, the considerations famously detailed by the Victorian poet and critic Matthew Arnold, which re- main the gold standard by which any Homeric translation is measured today. I attempt to walk the reader Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/daed/article-pdf/145/2/50/1830900/daed_a_00375.pdf by guest on 24 September 2021 through the process of rendering a modern translation in accordance with Arnold’s principles. “I t has more than once been suggested to me that I should translate Homer. That is a task for which I have neither the time nor the courage.”1 So begins Matthew Arnold’s classic essay “On Translating Ho- mer,” the North Star by which all subsequent trans- lators of Homer have steered, and the gold stan- dard by which all translations of Homer are judged. A reader will find Arnold’s principles referenced, directly or indirectly, in the introduction to most modern translations–Richmond Lattimore’s, Rob- ert Fagles’s, Robert Fitzgerald’s, and more recently Peter Green’s. Additionally, Arnold’s discussion of these principles serves as a primer of sorts for poets and writers of any stripe, not only those audacious enough to translate Homer. While the title of his essay implies that it is about translating the works of Homer, Arnold has little to CAROLINE ALEXANDER is the au- thor of The War That Killed Achil- say about the Odyssey, and he dedicates his attention les: The True Story of Homer’s Iliad to the Iliad. -

HUMANITIES INSTITUTE ANCİENT GREEK LİTERATURE Buckner B Trawick , Ph.D

HUMANITIES INSTITUTE ANCİENT GREEK LİTERATURE Buckner B Trawick , Ph.D. Updated by Frederic Will, Ph D. The Age of Epic Poetry (c. 900 -700 B.C.)* Historical Background. Greek people inhabited not only the southern part of the Balkan Peninsula (Hellas), but also part of the coast of Asia Minor, part of Italy, and many islands in the Mediterranean and Aegean seas, including Crete and Sicily. On the Balkan mainland, mountains and the surrounding sea led to divisions into many petty local states, which carried on continual warfare with each other. The primitive inhabitants were a mixture of three strains: (1) Pelasgians or Helladics. The earliest known inhabitants of the Greek mainland, they were perhaps related to the inhabitants of Asia Minor, and they probably were not Indo-Europeans. Little is known of them except what can be learned from legends and from the archeological discoveries of Schliemann and Evans. (2) Aegeo-Cretans. They were probably of Mediterranean origin and probably blended with the Pelasgians c. 1800-1400 B.C. (3) Northern Indo- Europeans. Variously called Achaeans, Danaans, and Hellenes, these people probably migrated from the north of Greece c. 2000- 1000 B.C. After 1150 B.C. there were three rather distinct racial groups: (1) Dorians. Their main settlements were the Peloponnesus, the Corinthian Isthmus, the southwest portion of Asia Minor, Crete, Sicily, and parts of Italy; their principal cities were Sparta, Corinth, and Syracuse. The Dorians were warlike, reserved, and devout. Their dialect was terse and rugged. They perfected the. “stately choral ode.” (2) Aeolians. The principal Aeolian settlements were Boeotia, Lesbos, and northwestern Asia Minor. -

On the Laws and Practice of Horse Racing

^^^g£SS/^^ GIFT OF FAIRMAN ROGERS. University of Pennsylvania Annenherg Rare Book and Manuscript Library ROUS ON RACING. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 with funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/onlawspracticeOOrous ON THE LAWS AND PRACTICE HORSE RACING, ETC. ETC. THE HON^T^^^ ADMIRAL ROUS. LONDON: A. H. BAILY & Co., EOYAL EXCHANGE BUILDINGS, COENHILL. 1866. LONDON : PRINTED BY W. CLOWES AND SONS, STAMFORD STREET, AND CHAKING CROSS. CONTENTS. Preface xi CHAPTER I. On the State of the English Turf in 1865 , . 1 CHAPTER II. On the State of the La^^ . 9 CHAPTER III. On the Rules of Racing 17 CHAPTER IV. On Starting—Riding Races—Jockeys .... 24 CHAPTER V. On the Rules of Betting 30 CHAPTER VI. On the Sale and Purchase of Horses .... 44 On the Office and Legal Responsibility of Stewards . 49 Clerk of the Course 54 Judge 56 Starter 57 On the Management of a Stud 59 vi Contents. KACma CASES. PAGE Horses of a Minor Age qualified to enter for Plates and Stakes 65 Jockey changed in a Race ...... 65 Both Jockeys falling abreast Winning Post . 66 A Horse arriving too late for the First Heat allowed to qualify 67 Both Horses thrown—Illegal Judgment ... 67 Distinction between Plate and Sweepstakes ... 68 Difference between Nomination of a Half-bred and Thorough-bred 69 Whether a Horse winning a Sweepstakes, 23 gs. each, three subscribers, could run for a Plate for Horses which never won 50^. ..... 70 Distance measured after a Race found short . 70 Whether a Compromise was forfeited by the Horse omitting to walk over 71 Whether the Winner distancing the Field is entitled to Second Money 71 A Horse objected to as a Maiden for receiving Second Money 72 Rassela's Case—Wrong Decision ... -

Morgan Horses

The 12th Annual NATIONAL MORGAN HORSE SHOW Sponsored by: Saturday Evening Friday Evening 7:00 P. M. 7:00 P. M. Sunday Saturday Afternoon Afternoon 1:00 P. M. 1:00 P. M. PERFORMANCE BREED CLASSES CLASSES For Stallions and Saddle, Harness, Mares: Colts and Pleasure. Utility Fillies and Equitation THE MORGAN HORSE CLUB Watch The Foundation Breed of America Perform. TRI-COUNTY FAIR GROUNDS NORTHAMPTON, MASS. July 30, 31 and August 1, 1954 Adults $1.00 Children - under 12 - 50' A LAW FOR IT . by 1939 Vermont Legislature "There oughta be a law agin it," is a favorite expresion of Vermonters. Sometimes they reverse themselves and make a law "for it" as they did in 1939 when the legislature passed the following resolution: "Whereas, this is the year recognized as the 150th anniversa y of the famous horse 'Justin Morgan,' which horse not only established a recognized breed of horses named for a single individual, but brought fame th•tzugh his descendants to Vermont and thousands of dollars to Vermonters. "The name Morgan has come to mean beauty, spirit, and action to all lovers of the horse; and the Morgan horses fo• many years held the world's record for trotting horses, and "Whereas the Morgan blood is recognized as foundation stock for the American Saddle Horse, for the American Trotting Horse, and for the Tennessee Walking Horse. In each of these three breeds, the Morgan horse is recognized as a foundation, and therefore, with the recognition of its value to the horse b seeders of the nation, and recognition that it was in Vermont that Morgan -

Study Questions Helen of Troycomp

Study Questions Helen of Troy 1. What does Paris say about Agamemnon? That he treated Helen as a slave and he would have attacked Troy anyway. 2. What is Priam’s reaction to Paris’ action? What is Paris’ response? Priam is initially very upset with his son. Paris tries to defend himself and convince his father that he should allow Helen to stay because of her poor treatment. 3. What does Cassandra say when she first sees Helen? What warning does she give? Cassandra identifies Helen as a Spartan and says she does not belong there. Cassandra warns that Helen will bring about the end of Troy. 4. What does Helen say she wants to do? Why do you think she does this? She says she wants to return to her husband. She is probably doing this in an attempt to save lives. 5. What does Menelaus ask of King Priam? Who goes with him? Menelaus asks for his wife back. Odysseus goes with him. 6. How does Odysseus’ approach to Priam differ from Menelaus’? Who seems to be more successful? Odysseus reasons with Priam and tries to appeal to his sense of propriety; Menelaus simply threatened. Odysseus seems to be more successful; Priam actually considers his offer. 7. Why does Priam decide against returning Helen? What offer does he make to her? He finds out that Agamemnon sacrificed his daughter for safe passage to Troy; Agamemnon does not believe that is an action suited to a king. Priam offers Helen the opportunity to become Helen of Troy. 8. What do Agamemnon and Achilles do as the rest of the Greek army lands on the Trojan coast? They disguise themselves and sneak into the city. -

Pause in Homeric Prosody

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/140838 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-09-26 and may be subject to change. AUDIBLE PUNCTUATION Performative Pause in Homeric Prosody Audible Punctuation: Performative Pause in Homeric Prosody Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen op gezag van de rector magnificus prof. dr. Th.L.M. Engelen, volgens besluit van het college van decanen in het openbaar te verdedigen op donderdag 21 mei 2015 om 14.30 uur precies door Ronald Blankenborg geboren op 23 maart 1971 te Eibergen Promotoren: Prof. dr. A.P.M.H. Lardinois Prof. dr. J.B. Lidov (City University New York, Verenigde Staten) Manuscriptcommissie: Prof. dr. M.G.M. van der Poel Prof. dr. E.J. Bakker (Yale University, Verenigde Staten) Prof. dr. M. Janse (Universiteit Gent, België) Copyright©Ronald Blankenborg 2015 ISBN 978-90-823119-1-4 [email protected] [email protected] All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the author. Printed by Maarse Printing Cover by Gijs de Reus Audible Punctuation: Performative Pause in Homeric Prosody Doctoral Thesis to obtain the degree of doctor from Radboud University Nijmegen on the authority of the Rector Magnificus prof. -

Fashioning a Return to Africa in Omeros Srila Nayak

ariel: a review of international english literature Vol. 44 No. 2–3 Pages 1–28 Copyright © 2014 The Johns Hopkins University Press and the University of Calgary “Nothing in that Other Kingdom”: Fashioning a Return to Africa in Omeros Srila Nayak Abstract: What are we to make of Achille’s imaginary return to Africa in Derek Walcott’s Omeros? Is it a rejection of Walcott’s ear- lier theme of postcolonial nostalgia for lost origins? Does it lead to a different conception of postcolonial identity away from notions of new world hybridity and heterogeneity that Walcott had es- poused earlier, or is it a complex figuring of racial identity for the Afro-Caribbean subject? My essay answers these questions through a reading of the specific intertextual moments in the poem’s return to Africa passage. The presence of allusions and textual fragments from Virgil’s Aeneid, Homer’s Odyssey, and James Joyce’s Ulysses in this particular passage of Omeros (Book 3) has not received much critical attention so far. Through the use of these modular texts, I argue that Omeros not only transforms the postcolonial genre of a curative return to origins and fashions a distinctive literary landscape but also imagines a postcolonial subjectivity that nego- tiates the polarity between origins and the absence of origins or a fragmented new world identity. Keywords: Derek Walcott; Omeros; intertextuality; postcolonial adaptation; epic canon; paternity Derek Walcott’s Omeros (1990) is an epic of Caribbean life in Saint Lucia and a retelling of the trans-Atlantic histories of descendants of slaves. Omeros’ self-referentiality as epic is signaled by its many ad- aptations of Homeric proper names, plot, and themes to structure a comparison between Aegean narratives of the Iliad and the Odyssey and black diasporic experiences in the West Indies.