Finding Liability for Korey Stringer's Death

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evaluating Nfl Player Health and Performance: Legal and Ethical Issues

UNIVERSITY of PENNSYLVANIA LAW REVIEW Founded 1852 Formerly AMERICAN LAW REGISTER © 2017 University of Pennsylvania Law Review VOL. 165 JANUARY 2017 NO. 2 ARTICLE EVALUATING NFL PLAYER HEALTH AND PERFORMANCE: LEGAL AND ETHICAL ISSUES JESSICA L. ROBERTS, I. GLENN COHEN, CHRISTOPHER R. DEUBERT & HOLLY FERNANDEZ LYNCH† This Article follows the path of a hypothetical college football player with aspirations to play in the National Football League, explaining from a legal and † George Butler Research Professor, Director of Health Law & Policy Institute, University of Houston Law Center, 2015–2018 Greenwall Faculty Scholar in Bioethics; Professor, Harvard Law School, Faculty Director of the Petrie–Flom Center for Health Law Policy, Biotechnology, and Bioethics, Co-Lead of the Law and Ethics Initiative, Football Players Health Study at Harvard University; Senior Law and Ethics Associate, Law and Ethics Initiative for the Football Players Health Study at Harvard University; Executive Director, Petrie–Flom Center for Health Law Policy, Biotechnology, and Bioethics, Faculty, Harvard Medical School, Center for Bioethics, Co- Lead, Law and Ethics Initiative, Football Players Health Study at Harvard University, respectively. Cohen, Deubert, and Lynch received salary support from the Football Players Health Study at Harvard University (FPHS), a transformative research initiative with the goal of improving the health of professional football players. About, FOOTBALL PLAYERS HEALTH STUDY HARV. U., https://footballplayershealth.harvard.edu/about/ [https://perma.cc/UN5R-D82L]. Roberts has also received payment as a consultant for the FPHS. The Football Players Health Study was created pursuant to an agreement between Harvard University and the National Football League Players Association (227) 228 University of Pennsylvania Law Review [Vol. -

SUDDEN DEATH © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT for SALE OR DISTRIBUTIONIN SPORT and PHYSICALNOT for SALE ACTIVITY OR DISTRIBUTION

© Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION SECOND EDITION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALEPREVENTING OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION SUDDEN DEATH © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTIONIN SPORT AND PHYSICALNOT FOR SALE ACTIVITY OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION Edited by: © Jones & DouglasBartlett Learning, J. Casa, LLC PhD, ATC, FACSM,© Jones FNATA& Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTIONChief Executive Offi cer, Korey Stringer InstituteNOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION Director, Athletic Training Education Professor, Department of Kinesiology Research Associate, Human Performance Laboratory © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC College of Agriculture, Health,© Jones and Natural & Bartlett Resources Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION University of Connecticut,NOT FOR Storrs, SALE CT OR DISTRIBUTION Rebecca L. Stearns, PhD, ATC Chief Operating Offi cer, Korey Stringer Institute © Jones & BartlettAssistant Professor, Learning, Department LLC of Kinesiology © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FORCollege SALE of Agriculture,OR DISTRIBUTION Health, and Natural Resources NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION © Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC. NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION. -

TOUCHDOWN CLUB Congratulations

13227_Cover:X 1/8/12 2:46 PM Page 1 WALTER CAMP FOOTBALL FOUNDATION Forty-Fifth Annual National Awards Dinner Yale University Commons New Haven, Connecticut January 14, 2012 13227_001-029:X 1/9/12 4:36 PM Page 1 P.O. BOX 1663 • NEW HAVEN, CONNECTICUT 06507 • TEL (203) 288-CAMP • www.waltercamp.org January 14, 2012 Dear Friends of Walter Camp: On behalf of the Officers – James Monico, William Raffone, Robert Kauffman, Timothy O’Brien and Michael Madera – Board of Governors and our all-volunteer membership, welcome to the 45th Annual Walter Camp Football Foundation national awards dinner and to the City of New Haven. Despite a challenging economy, the Walter Camp Football Foundation continues to thrive and succeed. We are thankful and grateful for the support of our sponsors, business partners, advertisers and event attendees. Tonight’s dinner sponsored by First Niagara Bank is the signature event for this All-America weekend along with being the premier college football awards dinner in the country. Since Thursday, the Walter Camp All-Americans, Alumni and major award winners have had a significant and positive impact on this city, its youth and the greater community. We remain committed to perpetuating the ideals and work of Walter Camp both on and off the gridiron. Our community outreach has included a Stay In School Rally for three thousand 7th and 8th graders at the Floyd Little Athletic Center, visits to seven hospitals and rehabilitation centers, and a fan festival for families and youth to meet and greet our guests. The Walter Camp membership congratulates the 2011 All-Americans and major award winners for their distinguished athletic achievements and for their ongoing commitment to service and to community. -

Can Summer Training Camp Practices Land NFL Head Coaches in Hot Water? Timothy Patrick Hayden

Marquette Sports Law Review Volume 20 Article 6 Issue 2 Spring Can Summer Training Camp Practices Land NFL Head Coaches in Hot Water? Timothy Patrick Hayden Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw Part of the Entertainment and Sports Law Commons Repository Citation Timothy Patrick Hayden, Can Summer Training Camp Practices Land NFL Head Coaches in Hot Water?, 20 Marq. Sports L. Rev. 441 (2010) Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/sportslaw/vol20/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CAN SUMMER TRAINING CAMP PRACTICES LAND NFL HEAD COACHES IN HOT WATER? TIMOTHY PATRICK HAYDEN* I. INTRODUCTION When a football player dies from heat stroke, Americans watch the news telecast or read about the story. We think about all of the money the school, organization, or coach may have to pay in a wrongful death lawsuit. We feel sorrow for the player, and the player's family, but then we quickly forget about it, and go about our day. However, what if it was your son that died from heat stroke during a football practice? Envision your son telling you how excited he is to be in the National Football League (NFL), and how he is looking forward to the start of a new season. It is a hot summer day in training camp, and your son is hitting, conditioning, and working as hard as he can. The practice is nearing the three-hour mark, and your son is feeling hot, tired, and sore. -

2016 Nfl Draft Facts & Figures

Minnesota Vikings 2016 Draft Guide MINNESOTA VIKINGS PRESEASON WEEK DAY DATE OPPONENT TIME (CT) TV RADIO P1 Friday Aug. 12 at Cincinnati Bengals 6:30 p.m. FOX 9 KFAN / KTLK P2 Thursday Aug. 18 at Seattle Seahawks 9:00 p.m. FOX 9 KFAN / KTLK P3 Sunday Aug. 28 San Diego Chargers Noon FOX 9 KFAN / KTLK P4 Thursday Sept. 1 Los Angeles Rams 7:00 p.m. FOX 9 KFAN / KTLK REGULAR SEASON WEEK DAY DATE OPPONENT TIME (CT) TV RADIO 1 Sunday Sept. 11 at Tennessee Titans Noon FOX KFAN / KTLK 2 Sunday Sept. 18 Green Bay Packers 7:30 p.m. NBC KFAN / KTLK 3 Sunday Sept. 25 at Carolina Panthers Noon FOX KFAN / KTLK 4 Monday Oct. 3 New York Giants 7:30 p.m. ESPN KFAN / KTLK 5 Sunday Oct. 9 Houston Texans Noon CBS KFAN / KTLK 6 Sunday Oct. 16 BYE WEEK 7 Sunday Oct. 23 at Philadelphia Eagles Noon* FOX KFAN / KTLK 8 Monday Oct. 31 at Chicago Bears 7:30 p.m. ESPN KFAN / KTLK 9 Sunday Nov. 6 Detroit Lions Noon* FOX KFAN / KTLK 10 Sunday Nov. 13 at Washington Redskins Noon* FOX KFAN / KTLK 11 Sunday Nov. 20 Arizona Cardinals Noon* FOX KFAN / KTLK 12 Thursday Nov. 24 at Detroit Lions 11:30 a.m. CBS KFAN / KTLK 13 Thursday Dec. 1 Dallas Cowboys 7:25 p.m. NBC/NFLN KFAN / KTLK 14 Sunday Dec. 11 at Jacksonville Jaguars Noon* FOX KFAN / KTLK 15 Sunday Dec. 18 Indianapolis Colts Noon* CBS KFAN / KTLK 16 Saturday Dec. 24 at Green Bay Packers Noon* FOX KFAN / KTLK 17 Sunday Jan. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—HOUSE August 2, 2001 1993 and Certainly As It Was in 1970

15768 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—HOUSE August 2, 2001 1993 and certainly as it was in 1970. As my friend Minnesota Vikings all- his truck and signed over his Pro Bowl Protecting our environment is a pri- pro wide receiver Cris Carter said yes- to the youth football team. That was ority for all Americans. To give this terday, ‘‘There was not a more well- Korey Stringer. function the attention it deserves real- liked player on our football team, but Mr. Speaker, Minnesota Vikings ly necessitates elevating the EPA to it’s far greater than about football.’’ owner Red McCombs summed it up well the Department of Environmental Pro- Korey was in his seventh season as a when he said, ‘‘We have lost a truly re- tection. H.R. 2694 does precisely this. Viking after he was drafted in the first markable man who was an outstanding In no small part, this commitment and round in 1995 as a 20-year-old from Ohio husband, father and football player.’’ elevation of the EPA signals to our State. Even though Korey was a native My good friend of many years, former world partners and to our own citizens of Warren, Ohio, he chose to make the Viking Joe Senser, who is now the that environmental protection and res- Twin Cities area his permanent home. radio voice of the Minnesota Vikings, toration is at the top of our policy pri- He was a huge man physically, 6 feet 4, said, ‘‘You will not find a better family orities. 335 pounds, and his heart was even big- man who loved his family more.’’ Besides elevating the EPA to a full ger. -

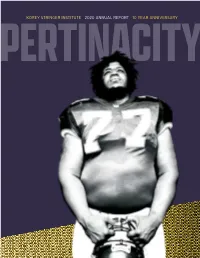

KOREY STRINGER INSTITUTE 2020 ANNUAL REPORT 10 YEAR ANNIVERSARY PERTINACITY MOVING FORWARD FASTER: a Reflection on 10 Years of the Korey Stringer Institute

KOREY STRINGER INSTITUTE 2020 ANNUAL REPORT 10 YEAR ANNIVERSARY PERTINACITY MOVING FORWARD FASTER: A Reflection on 10 Years of the Korey Stringer Institute Hello to our partners, collaborators, supporters, friends, and global network — What an awesome opportunity our first decade has been. Every day I pinch myself because it is an honor to do such meaningful work with such amazing people. The staff at KSI, now over 80 people strong, bubbles with THE MISSION OF THE KOREY STRINGER INSTITUTE inspiration, creativity, and passion. You just have to climb on board the wave of collective forward IS TO PROVIDE RESEARCH, EDUCATION, ADVOCACY, momentum and you are immediately the sense that KSI exhibits pertinacity catapulted to a destination closer to — persistent determination — when AND CONSULTATION TO MAXIMIZE PERFORMANCE, your goal. I had not known anything looking to overcome challenges like it prior, and I am wise enough to that have long faced those who do know it will likely never occur again. intense physical exercise as athletes, OPTIMIZE SAFETY, AND PREVENT SUDDEN DEATH But given my memorable past, having warfighters, or laborers. staff and volunteers who put in suffered life-threatening exertional the tough, thankless, and critical heat stroke at 16 years old, I can tell KSI has been unbelievably fortunate work overseeing research projects FOR THE ATHLETE, WARFIGHTER, AND LABORER. you that I will cherish every single to leverage connections in these and public health initiatives; to the second of this joyous experience. industries, along with active corporate partners who believed in collaborations in the academic and us; to the end user who showed faith I had a recent emotional experience medical space, to create a unique in what we could do to help them. -

70 Years Ago, Nfl First to Retire a Number

70 YEARS AGO, NFL FIRST TO RETIRE A NUMBER It is one of the greatest honors in professional sports -- the retirement of your uniform number. In 1935 -- 70 years ago -- the New York Giants retired the uniform number of receiver RAY FLAHERTY (No. 1), thus anointing the first professional athlete to have his name and number etched in eternity by his club. Since then, 122 players, plus the Seattle Seahawks by retiring the No. 12 to recognize their fans as their “12th man,” have had the honor bestowed upon them. This season, three men will be added to the fraternity -- Green Bay Packers’ great REGGIE WHITE (No. 92), San Diego Chargers Hall of Fame wide receiver LANCE ALWORTH (No. 19) and the Carolina Panthers’ late linebacker SAM MILLS (No. 51). When Green Bay President BOB HARLAN told White last year before the player’s death that his jersey would be retired, White emphasized how important it was to him. “He was thrilled,” says Harlan. “He kept saying what an honor that would be.” The Packers will conduct a halftime ceremony at their home opener on September 18 in which White will become the fifth Packer to have his number listed in the north end zone of Lambeau Field. On November 20, Alworth will join quarterback DAN FOUTS (No. 14) in having his number retired by the Chargers. “This is about as good as it gets,” says Alworth. “It’s a humbling experience.” The Carolina Panthers this summer honored Mills by retiring his No. 51 at halftime of their August 13 preseason game. -

Heat-Related Deaths in American Football: an Interdisciplinary Approach

Sport History Review, 2014, 45, 123-144 http://dx.doi.org/10.1123/shr.2014-0025 © 2014 Human Kinetics, Inc. Heat-Related Deaths in American Football: An Interdisciplinary Approach Jaime Schultz, W. Larry Kenney, and Andrew D. Linden Pennsylvania State University As observers of American football turn their attention to the crises of con- cussions, subconcussive hits, chronic traumatic encephalopathy, and attendant issues related to direct contact and collision, it may be easy to lose track of the too frequent occurrence of what experts refer to as a type of “indirect” fatality caused by “systemic failure as a result of exertion”: those associated with heat.1 Typically brought about by engaging in intense physical effort in hot and humid conditions, the vast majority of these deaths need not occur. Despite the growing scientific understanding of the problem, however, heat-related deaths persist, often surging at different points in history. It is not just an issue of science, then, but also an issue of culture and one that necessitates an interdisciplinary approach. Physicians have documented heat-related deaths in football since the early twentieth century, but it was the 2001 death of the Minnesota Vikings’ All Pro tackle, Korey Stringer, that put the public on notice. On July 30, the 37-year-old National Football League (NFL) veteran reported to training camp weighing 336 pounds and reportedly “in the best shape of his career.” But that summer’s brutal combination of heat and humidity in the upper Midwest pummeled the athletes without relent, with heat indices peaking at 110 degrees Fahrenheit (43 degrees Celsius). -

Football Award Winners

FOOTBALL AWARD WINNERS Consensus All-America Selections 2 Consensus All-Americans by School 17 National Award Winners 30 First Team All-Americans Below FBS 41 Postgraduate Scholarship Winners 73 Academic All-America Hall of Fame 82 Academic All-Americans by School 83 CONSENSUS ALL-AMERICA SELECTIONS In 1950, the National Collegiate Athletic Bureau (the NCAA’s service bureau) compiled the first official comprehensive roster of all-time All-Americans. The compilation of the All-America roster was supervised by a panel of analysts working in large part with the historical records contained in the files of the Dr. Baker Football Information Service. The roster consists of only those players who were first-team selections on one or more of the All-America teams that were selected for the national audience and received nationwide circulation. Not included are the thousands of players who received mention on All-America second or third teams, nor the numerous others who were selected by newspapers or agencies with circulations that were not primarily national and with viewpoints, therefore, that were not normally nationwide in scope. The following chart indicates, by year (in left column), which national media and organizations selected All-America teams. The headings at the top of each column refer to the selector (see legend after chart). ALL-AMERICA SELECTORS AA AP C CNN COL CP FBW FC FN FW INS L LIB M N NA NEA SN UP UPI W WCF 1889 – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – √ – 1890 – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – √ – 1891 – – – – – -

San Francisco 49Ers at Minnesota Vikings

MINNESOTASAN FRANCISCO VIKINGS 49ERS AT NEWAT MINNESOTA ENGLAND PATRIOTS VIKINGS SUNDAY,SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER OCTOBER 31, 27, 2010 2009 WEEK EIGHT - MINNESOTA VIKINGS (2-4) AT NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS (5-1) SUNDAY, OCTOBER 31, 2010 - GILLETTE STADIUM - 3:15 P.M. - FOX GAME SUMMARY The Minnesota Vikings (2-4) will fi nish the team’s stretch of three road games in four weeks this Sunday, October 31, against the New England Patriots (5-1). Kickoff at Gillette Stadium is set for 3:15 p.m. CT. Sunday’s game will be the Vikings ninth consecutive road game that will not start at noon central time (last noon road game was at Pittsburgh on 10/25/09). Of the 2010 VIKINGS SCHEDULE Vikings fi rst seven games in 2010, just two have been noon kickoff s. PRESEASON The Vikings have a 4-6-0 all-time record against the Patriots. Minnesota is 2-2 against New England Date Opponent Time (CT) TV at home and 2-4 on the road. Head Coach Brad Childress has faced the Patriots just one time, a 31-7 8/14 (Sat.) at St. Louis W 28-7 1-0 loss in Childress’ fi rst year leading the Vikings (10/30/06). 8/22 (Sun.) at San Francisco L 10-15 1-1 8/28 (Sat.) SEATTLE W 24-13 2-1 BROADCAST COVERAGE 9/2 (Thurs.) DENVER W 31-24 3-1 TELEVISION: FOX (Channel 9 in Minneapolis) REGULAR SEASON Play-by-Play: Thom Brennaman Analyst: Troy Aikman Date Opponent Time (CT) TV Sideline Reporter: Pam Oliver 9/9 (Thurs.) at New Orleans L 9-14 0-1 9/19 (Sun.) MIAMI L 10-14 0-2 9/26 (Sun.) DETROIT W 24-10 1-2 NATIONAL RADIO: Sports USA Radio Play-by-Play: Larry Kahn Analyst: Ross Tucker 10/3 (Sun.) Bye Sideline Reporter: Tony Graziani 10/11 (Mon.) at New York Jets L 20-29 1-3 10/17 (Sun.) DALLAS W 24-21 2-3 KFAN-AM 1130/KTLK 100.3-FM 10/24 (Sun.) at Green Bay L 24-28 2-4 Play-by-Play: Paul Allen Analyst: Pete Bercich 10/31 (Sun.) at New England 3:15 p.m. -

NCAA Division II-III Football Records (Award Winners)

Award Winners Consensus All-America Selections, 1889-2007 ............................ 126 Special Awards .............................................. 141 First-Team All-Americans Below Football Bowl Subdivision ..... 152 NCAA Postgraduate Scholarship Winners ........................................................ 165 Academic All-America Hall of Fame ............................................... 169 Academic All-Americans by School ..... 170 126 CONSENSUS All-AMERIca SELEctIONS Consensus All-America Selections, 1889-2007 In 1950, the National Collegiate Athletic Bureau (the NCAA’s service bureau) of players who received mention on All-America second or third teams, nor compiled the first official comprehensive roster of all-time All-Americans. the numerous others who were selected by newspapers or agencies with The compilation of the All-American roster was supervised by a panel of circulations that were not primarily national and with viewpoints, therefore, analysts working in large part with the historical records contained in the that were not normally nationwide in scope. files of the Dr. Baker Football Information Service. The following chart indicates, by year (in left column), which national media The roster consists of only those players who were first-team selections on and organizations selected All-America teams. The headings at the top of one or more of the All-America teams that were selected for the national au- each column refer to the selector (see legend after chart). dience and received nationwide circulation. Not