Iran: from Social to Political Change? Bernard Hourcade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Generations Feel When Brands Take a Stand

How Generations Feel When Brands Take a Stand ©Copyright 2018 Quester The Set-Up Quester is in the process of conducting a new joint project with 747 Insights and Collaborata: GENERATION NATION 2019: Defining America’s Gen Z, Millennials, Generation X and Boomers This study provides a comparison of attitudes and behaviors across these four cohorts, to expand upon current intelligence and cut to the core of what it means to be an American in 2019. Aided by technology, media, politics, and more, we can see Generational values shifting at a faster pace than we’ve ever seen before. One of the discussion areas centered around perceptions of whether brands should take a stand on social and political issues … So Let’s Recap Generation Nation - Should Brands Take a Stand? GEN Z MILLENNIALS They probably shouldn’t. It depends. It could cause tension, and employees may not Maybe … if it’s not too agree. extreme But it could be okay if it’s not offensive and they really believe in it. GEN X BOOMERS It’s not really my It’s their right, but they business – they can if might lose business. they want to. They probably shouldn’t do it. Unless But it’s probably not for it’s something really the right reasons. non-controversial. Generation Nation Brand Completion So we asked all of those questions about general brand perspective and Brand thoughts! finished all of the discussions. The Best Laid Plans … And then— one week later … The Reaction So we went back in and talked to about 100 people in each generation. -

The Satrap of Western Anatolia and the Greeks

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Eyal Meyer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons Recommended Citation Meyer, Eyal, "The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2473. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Abstract This dissertation explores the extent to which Persian policies in the western satrapies originated from the provincial capitals in the Anatolian periphery rather than from the royal centers in the Persian heartland in the fifth ec ntury BC. I begin by establishing that the Persian administrative apparatus was a product of a grand reform initiated by Darius I, which was aimed at producing a more uniform and centralized administrative infrastructure. In the following chapter I show that the provincial administration was embedded with chancellors, scribes, secretaries and military personnel of royal status and that the satrapies were periodically inspected by the Persian King or his loyal agents, which allowed to central authorities to monitory the provinces. In chapter three I delineate the extent of satrapal authority, responsibility and resources, and conclude that the satraps were supplied with considerable resources which enabled to fulfill the duties of their office. After the power dynamic between the Great Persian King and his provincial governors and the nature of the office of satrap has been analyzed, I begin a diachronic scrutiny of Greco-Persian interactions in the fifth century BC. -

What Makes a Leader Effective? U.S. Boomers, Xers, and Millennials Weigh In

WHITE PAPER - News and Insight for Learning, Development and HR Leaders What Makes a Leader Effective? U.S. Boomers, Xers, and Millennials Weigh In By Jennifer J. Deal, Sarah Stawiski, William A. Gentry, and Kristin L. Cullen Contents Introduction 3 Generational Cohorts 4 Survey Results: 5 What Makes a Leader Effective? Developing Leaders for All Generations 11 Conclusion 12 About the Research 13 Endnotes 13 About the Authors 14 Introduction Conventional wisdom suggests Generations at Work in the USA that Baby Boomers, Gen Xers, and Millennials in the United States are Most of the workforce in the U.S. is made up of three fundamentally different from one generations: Baby Boomers (born 1946 to 1963), Gen Xers another. And certainly there are (born 1964 to 1979), and Millennials (born after 1980).1,2,3 real differences—including the The post-war generation was called the Baby Boom way we dress, the way we consume because of the rapid increase in birth rate at the end of information, the music we listen World War II. Baby Boomers weren’t born when WWII to, and ideas about appropriate ended, but experienced post-war prosperity that resulted personal behavior. in middle-class Americans having access to utilities such Many organizational leaders are as central heating, running hot water, household anticipating a substantial upheaval appliances, televisions, and automobiles. Though during in work culture and expectations as their youth Baby Boomers were thought of as being more Millennials enter the workforce anti-authority,4 currently they are typically characterized and more Baby Boomers retire. But as materialistic workaholics who are at the top of the will there need to be wholesale authority structure, and are focused on their own personal changes in how leaders need to fulfillment, acquisition of things, status, and authority.5,6,7 behave to be effective? Generation X is the cohort born in the U.S. -

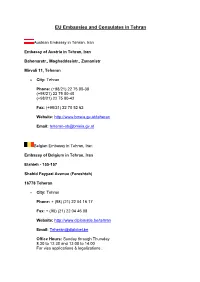

EU Embassies and Consulates in Tehran

EU Embassies and Consulates in Tehran Austrian Embassy in Tehran, Iran Embassy of Austria in Tehran, Iran Bahonarstr., Moghaddasistr., Zamanistr Mirvali 11, Teheran City: Tehran Phone: (+98/21) 22 75 00-38 (+98/21) 22 75 00-40 (+98/21) 22 75 00-42 Fax: (+98/21) 22 70 52 62 Website: http://www.bmeia.gv.at/teheran Email: [email protected] Belgian Embassy in Tehran, Iran Embassy of Belgium in Tehran, Iran Elahieh - 155-157 Shahid Fayyazi Avenue (Fereshteh) 16778 Teheran City: Tehran Phone: + (98) (21) 22 04 16 17 Fax: + (98) (21) 22 04 46 08 Website: http://www.diplomatie.be/tehran Email: [email protected] Office Hours: Sunday through Thursday 8.30 to 12.30 and 13.00 to 14.00 For visa applications & legalizations : Sunday through Tuesday from 8.30 to 11.30 AM Bulgarian Embassy in Tehran, Iran Bulgarian Embassy in Tehran, Iran IR Iran, Tehran, 'Vali-e Asr' Ave. 'Tavanir' Str., 'Nezami-ye Ganjavi' Str. No. 16-18 City: Tehran Phone: (009821) 8877-5662 (009821) 8877-5037 Fax: (009821) 8877-9680 Email: [email protected] Croatian Embassy in Tehran, Iran Embassy of the Republic of Croatia in Tehran, Iran 1. Behestan 25 Avia Pasdaran Tehran, Islamic Republic of Iran City: Tehran Phone: 0098 21 258 9923 0098 21 258 7039 Fax: 0098 21 254 9199 Email: [email protected] Details: Covers the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Details: Ambassador: William Carbó Ricardo Cypriot Embassy in Tehran, Iran Embassy of the Republic of Cyprus in Tehran, Iran 328, Shahid Karimi (ex. -

The Politics of Parthian Coinage in Media

The Politics of Parthian Coinage in Media Author(s): Farhang Khademi Nadooshan, Seyed Sadrudin Moosavi, Frouzandeh Jafarzadeh Pour Reviewed work(s): Source: Near Eastern Archaeology, Vol. 68, No. 3, Archaeology in Iran (Sep., 2005), pp. 123-127 Published by: The American Schools of Oriental Research Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25067611 . Accessed: 06/11/2011 07:31 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The American Schools of Oriental Research is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Near Eastern Archaeology. http://www.jstor.org The Parthians (174 BCE-224CE) suc- , The coins discussed here are primarily from ceeded in the the Lorestan Museum, which houses the establishing longest jyj^' in the ancient coins of southern Media.1 However, lasting empire J0^%^ 1 Near East.At its Parthian JF the coins of northern Media are also height, ^S^ considered thanks to the collection ruleextended Anatolia to M from ^^^/;. housed in the Azerbaijan Museum theIndus and the Valley from Ef-'?S&f?'''' in the city of Tabriz. Most of the Sea to the Persian m Caspian ^^^/// coins of the Azerbaijan Museum Farhang Khademi Gulf Consummate horsemen el /?/ have been donated by local ^^ i Nadooshan, Seyed indigenoustoCentral Asia, the ? people and have been reported ?| ?????J SadrudinMoosavi, Parthians achieved fame for Is u1 and documented in their names. -

Megillat Esther

The Steinsaltz Megillot Megillot Translation and Commentary Megillat Esther Commentary by Rabbi Adin Even-Israel Steinsaltz Koren Publishers Jerusalem Editor in Chief Rabbi Jason Rappoport Copy Editors Caryn Meltz, Manager The Steinsaltz Megillot Aliza Israel, Consultant Esther Debbie Ismailoff, Senior Copy Editor Ita Olesker, Senior Copy Editor Commentary by Chava Boylan Rabbi Adin Even-Israel Steinsaltz Suri Brand Ilana Brown Koren Publishers Jerusalem Ltd. Carolyn Budow Ben-David POB 4044, Jerusalem 91040, ISRAEL Rachelle Emanuel POB 8531, New Milford, CT 06776, USA Charmaine Gruber Deborah Meghnagi Bailey www.korenpub.com Deena Nataf Dvora Rhein All rights reserved to Adin Steinsaltz © 2015, 2019 Elisheva Ruffer First edition 2019 Ilana Sobel Koren Tanakh Font © 1962, 2019 Koren Publishers Jerusalem Ltd. Maps Editors Koren Siddur Font and text design © 1981, 2019 Koren Publishers Jerusalem Ltd. Ilana Sobel, Map Curator Steinsaltz Center is the parent organization Rabbi Dr. Joshua Amaru, Senior Map Editor of institutions established by Rabbi Adin Even-Israel Steinsaltz Rabbi Alan Haber POB 45187, Jerusalem 91450 ISRAEL Rabbi Aryeh Sklar Telephone: +972 2 646 0900, Fax +972 2 624 9454 www.steinsaltz-center.org Language Experts Dr. Stéphanie E. Binder, Greek & Latin Considerable research and expense have gone into the creation of this publication. Rabbi Yaakov Hoffman, Arabic Unauthorized copying may be considered geneivat da’at and breach of copyright law. Dr. Shai Secunda, Persian No part of this publication (content or design, including use of the Koren fonts) may Shira Shmidman, Aramaic be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles or reviews. -

Life As a Baby Boomer

Chapter 6 Life as a Baby Boomer Red Diaper Baby At the outset of the classic 60’s film Yellow Submarine, a cartoon Ringo Starr, heads down, hands in his pockets, walking across the screen muttering over and over to himself in a sad resigned voice nothing ever happens to me … nothing ever happens to me… That was me. At least it was a part of me that I was conscious of and I distinctly remember it even now, many years since. It was before the Beatles, including Ringo, the 1950’s had ended and the sixties had literally begun, 1960, 1961,1962, and I and was getting impatient to get on with it, go to high school. The huge fins growing out of ever-longer and longer automobiles were becoming passé, and the custom of buying a brand-new car every single year, trading in of course the old one, was being replaced by an exodus to the suburbs where cars properly belonged. A decade before, the automobile had already pushed out the trolleys in Newark, where I grew up, so that I only knew their obsolete tracks, the way our 1952 green Desoto skidded when we drove on Clinton Avenue. I was born in 1949 the quintessential early baby boomer, now entering the early years of the baby boomers’ grand entry into Medicare and Social Security. It will go on for the next several decades until there are no more to enter, no one left alive born before 1965. One of my first memories is sitting in front of a TV at a neighbor’s house, the one on my block among the first to buy a TV set, it being heavily marketed immediately in the New York area. -

Iran's Nuclear Program: Tehran's Compliance with International

Iran’s Nuclear Program: Tehran’s Compliance with International Obligations Updated August 18, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R40094 SUMMARY R40094 Iran’s Nuclear Program: Tehran’s Compliance August 18, 2021 with International Obligations Paul K. Kerr Several U.N. Security Council resolutions adopted between 2006 and 2010 required Iran to Specialist in cooperate fully with the International Atomic Energy Agency’s (IAEA’s) investigation of its Nonproliferation nuclear activities, suspend its uranium enrichment program, suspend its construction of a heavy- water reactor and related projects, and ratify the Additional Protocol to its IAEA safeguards agreement. Iran did not comply with most of the resolutions’ provisions. However, Tehran has implemented various restrictions on, and provided the IAEA with additional information about, the government’s nuclear program pursuant to the July 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), which Tehran concluded with China, France, Germany, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States. On the JCPOA’s Implementation Day, which took place on January 16, 2016, all of the previous resolutions’ requirements were terminated. The nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) and U.N. Security Council Res olution 2231, which the Council adopted on July 20, 2015, compose the current legal framework governing Iran’s nuclear program. The United States attempted in 2020 to reimpose sanctions on Iran via a mechanism provided for in Resolution 2231. However, the Security Council did not do so. Iran and the IAEA agreed in August 2007 on a work plan to clarify outstanding questions regarding Tehran’s nuclear program. The IAEA had essentially resolved most of these issues, but for several years the agency still had questions concerning “possible military dimensions to Iran’s nuclear programme.” A December 2, 2015, report to the IAEA Board of Governors from then-agency Director General Yukiya Amano contains the IAEA’s “final assessment on the resolution” of the outstanding issues. -

PATTERNS of DISCONTENT: WILL HISTORY REPEAT in IRAN? by Michael Rubin and Patrick Clawson *

PATTERNS OF DISCONTENT: WILL HISTORY REPEAT IN IRAN? By Michael Rubin and Patrick Clawson * While international attention is focused on Iran’s nuclear program and President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s bombast, Iranian society itself is facing turbulent times. Increasingly, patterns are re-emerging that mirror events in the years before the Islamic revolution. These include political disillusionment, domestic protest, government failure to match public expectations of economic success, and labor unrest. Nevertheless, the Islamic regime has learned the lessons of the past and is determined not to repeat them, even as political discord crescendos. This essay is derived from the authors’ recent book, Eternal Iran: Continuity and Chaos (Palgrave-Macmillan, 2005). Mahmud Ahmadinejad’s victory in Iran’s Ahmadinejad’s 2003 election as mayor of 2005 Presidential elections shocked both Tehran. Iranians and the West. “Winner in Iran calls The election of Ahmadinejad was only the for Unity; Reformists Reel,” headlined The latest in a series of surprises that Iran has New York Times.1 Most Western produced in recent decades. Indeed, a review governments assumed that former President of Iran's history over the last thirty years and Expediency Council chairman Ali Akbar suggests that Iran excels at surprising its own Hashemi Rafsanjani would win. 2 Many people and the world. This does not mean academics also were surprised. Few paid any that history will be repeated. But it is worth heed to the former blacksmith’s son who rose bearing in mind that nearly three decades to become mayor of Tehran. Brown after the shah's grip on power began to falter, University anthropologist William O. -

New Climatic Zones in Iran: a Comparative Study of Different Empirical Methods and Clustering Technique

New Climatic Zones in Iran: A Comparative Study of Different Empirical Methods and Clustering Technique Faezeh Abbasi University of Tehran Saeed Bazgeer ( [email protected] ) University of Tehran https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7044-0528 Parviz Rezazadeh Kalehbasti I.R. of Iran Meteorological Organization (IRIMO) Ebrahim Asadi Oskoue Atmospheric Science and Meteorological Research Center Masoud Haghighat I.R. of Iran Meteorological Organization (IRIMO) Pouya Rezazadeh Kalebasti Stanford University, Research Article Keywords: Climatic classication, Climatic zones, Cluster analysis, Precipitation gradient, Thornthwaite and Mather method Posted Date: June 2nd, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-570400/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License 1 Faezeh Abbasi1, Saeed Bazgeer2*, Parviz Rezazadeh Kalehbasti3, Ebrahim Asadi Oskoue4, 2 Masoud Haghighat5, Pouya Rezazadeh Kalebasti6 3 4 5 New Climatic Zones in Iran: A Comparative Study of Different Empirical Methods and 6 Clustering Technique 7 8 1Faezeh Abbasi, Ph.D., Agricultural Climatology, Department of Physical Geography, Faculty 9 of Geography, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran 10 e-mail address: [email protected] 11 12 2*Saeed Bazgeer, Corresponding author, Assistant Professor, Department of Physical 13 Geography, Faculty of Geography, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran 14 e-mail address: [email protected] 15 Orcid Id: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7044-0528 16 17 3Parviz Rezazadeh Kalehbasti, Synoptic Meteorologist, I.R. of Iran Meteorological 18 Organization (IRIMO), Tehran, Iran 19 e-mail address: [email protected] 20 21 4Ebrahim Asadi Oskoue, Assistant Professor, Department of Agricultural Meteorology, 22 Atmospheric Science and Meteorological Research Center, Tehran, Iran 23 e-mail address: [email protected] 24 25 5Masoud Haghighat, Agricultural Meteorologist, I.R. -

International Workshop on “Adaptation to Water Scarcity and Basin-Connected Cities”

Call for Papers/ Country Reports International workshop on “Adaptation to Water Scarcity and Basin-connected Cities” 10-12 December 2018, Mashhad-Iran On the occasion of the 8th Asian G-WADI and 2nd IDI Meetings Background Water scarcity is the lack of sufficient available water resources to meet demands of water usage within a region. This condition arises as consequence of a high rate of accumulated demand from all water-using sectors including agriculture, domestic, industry and environment compared with available supply, under the prevailing institutional arrangements and infrastructural conditions. The international workshop on “Adaptation to Water Scarcity and Basin- Connected Cities” is designed to bring together researchers and practitioners alike including governmental officials, private and public sectors, water managers, urban planners as well as decision and policy makers engaged in various aspects of water scarcity adaptation and the new concept basin- connected cities. The workshop provide contribution the implementation of the Eighth Phase of IHP (2014- 2021) “Water Security: Addressing Local, Regional and Global Challenges” and in particular, within the activities of the two-flagship prorgamme of IHP IDI and G-WADI. This international workshop provides a unique opportunity for various specialists to exchange ideas and experiences. International Organizers The workshop will be held on the occasion of the 8th Asian G-WADI and 2nd International Drought Initiative (IDI) meetings in Mashhad, Iran, 10-12 December 2018, organized -

Climatic and Thermal Comfort Research Orientations in Outdoor Spaces: from 1999 to 2017 in Iran

International Journal of Architecture and Urban Development E-ISSN 2345-2331 © 2019 IAU Archive of Vol. SID 9, No.4. P 45-60. Autumn 2019 Development Urban and Of Architecture Journal International Climatic and thermal comfort research orientations in outdoor spaces: From 1999 to 2017 in Iran 1*Bahareh Bannazadeh, 2Shahin Heidari., 3Ali Jazaeri 1*PhD Candidate, University of Tehran, Kish International Complex Tehran, Iran. 2Professor of Architecture, University of Tehran, Iran. 3M.Sc. in architectural engineering, University of Shiraz, Shiraz, Iran. Recieved 10.06.2019; Accepted 22.10.2019 ABS TRACT: The satisfaction level with an environment differs among individuals caused by social, psychological and physical factors. One of the environmental factors affecting physical and mental satisfaction is the space thermal condition. In recent years, the importance of thermal comfort has been accentuated due to the climate change and global warming. The objective of the present s tudy is to identify the main concepts raised in Iran outdoor thermal comfort by s tudying and classifying the s tudies in this field to identify the characteris tics of each category. Thus, this s tudy reviews 142 papers written in Iran published in the period between 1999 and 2017. The papers are firs t classified into two main categories (including fundamental s tudies on thermal comfort and practical s tudies) and three secondary categories that are subsets of the second main category (macroscale, mesoscale, and microscale s tudies). Each category is then s tudied and analyzed in more details according to the regions and climates considered, methodology and research means, effective factors and thermal indices used for evaluation.