Fall 2002 Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Libro ING CAC1-36:Maquetación 1.Qxd

© Enrique Montesinos, 2013 © Sobre la presente edición: Organización Deportiva Centroamericana y del Caribe (Odecabe) Edición y diseño general: Enrique Montesinos Diseño de cubierta: Jorge Reyes Reyes Composición y diseño computadorizado: Gerardo Daumont y Yoel A. Tejeda Pérez Textos en inglés: Servicios Especializados de Traducción e Interpretación del Deporte (Setidep), INDER, Cuba Fotos: Reproducidas de las fuentes bibliográficas, Periódico Granma, Fernando Neris. Los elementos que componen este volumen pueden ser reproducidos de forma parcial siem- pre que se haga mención de su fuente de origen. Se agradece cualquier contribución encaminada a completar los datos aquí recogidos, o a la rectificación de alguno de ellos. Diríjala al correo [email protected] ÍNDICE / INDEX PRESENTACIÓN/ 1978: Medellín, Colombia / 77 FEATURING/ VII 1982: La Habana, Cuba / 83 1986: Santiago de los Caballeros, A MANERA DE PRÓLOGO / República Dominicana / 89 AS A PROLOGUE / IX 1990: Ciudad México, México / 95 1993: Ponce, Puerto Rico / 101 INTRODUCCIÓN / 1998: Maracaibo, Venezuela / 107 INTRODUCTION / XI 2002: San Salvador, El Salvador / 113 2006: Cartagena de Indias, I PARTE: ANTECEDENTES Colombia / 119 Y DESARROLLO / 2010: Mayagüez, Puerto Rico / 125 I PART: BACKGROUNG AND DEVELOPMENT / 1 II PARTE: LOS GANADORES DE MEDALLAS / Pasos iniciales / Initial steps / 1 II PART: THE MEDALS WINNERS 1926: La primera cita / / 131 1926: The first rendezvous / 5 1930: La Habana, Cuba / 11 Por deportes y pruebas / 132 1935: San Salvador, Atletismo / Athletics -

Campeonato Nacional Abierto De Atletismo 2019

Fed Mx de Asoc Atletismo Athletic Club Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 12:09 PM 02/06/2019 Page 1 Campeonato Nacional Abierto de Atletismo 2019 - 31/05/2019 to 02/06/2019 Selectivo para los Juegos Panamericanos, Lima Perú Estadio Olímpico de Ciudad Deportiva Resultados Femenil 100 Metros Planos Abierta ================================================================================== REC MEX: 11,09 19/06/1999 Liliana Allen Doll, IPN REC NAL: 11,28 06/07/2001 Lilliana Allen Doll, Tabasco Nombre Year Team Prelims Wind H# Alternate ================================================================================== Preliminaries 1 Hermosillo G, Mayra Li Jalisco 11,62Q +0.0 2 .168 2 Talamante A, Maria Merce Sonora 11,95Q -0.2 1 .180 3 Aguillon R, Dania Amaris Tamaulipas 11,65Q +0.0 2 .186 4 Ramirez C, Ana Cristina Tlaxcala 12,22Q -0.2 1 .253 5 Flores H, Iza Daniela Sinaloa 12,13Q +0.0 2 .197 6 Ortiz H, Monica Patricia Nuevo León 12,35Q -0.2 1 .152 7 Araujo A, Karen Yanina Nuevo León 12,22q +0.0 2 .164 8 Jurado O, Aurora Olivia Ciudad de México 12,36q +0.0 2 .165 9 Espinosa S, Araceli Itze Ciudad de México 12,41 +0.0 2 .250 10 Pererz P, Teresa Michoacán 12,65 -0.2 1 .171 Femenil 100 Metros Planos Abierta ====================================================================================== REC MEX: 11,09 19/06/1999 Liliana Allen Doll, IPN REC NAL: 11,28 06/07/2001 Lilliana Allen Doll, Tabasco Nombre Year Team Finales Wind Points Alternate ====================================================================================== Finales 1 Aguillon R, Dania -

Cardiff 2016 F&F.Qxp WHM F&F

IAAF/Cardiff University WORLD HALF MARATHON CHAMPIONSHIPS FACTS & FIGURES Incorporating the IAAF World Half Marathon Championships (1992-2005/2008-2010-2012-2014) IAAF World Road Running Championships 2006/2007 Past Championships...............................................................................................1 Past Medallists .......................................................................................................1 Overall Placing Table..............................................................................................5 Most Medals Won...................................................................................................6 Youngest & Oldest..................................................................................................7 Most Appearances by athlete.................................................................................7 Most Appearances by country................................................................................8 Country Index .......................................................................................................10 World Road Race Records & Best Performances at 15Km, 20Km & Half Mar .........39 Progression of World Record & Best Performance at 15Km, 20Km & Half Mar .......41 CARDIFF 2016 ★ FACTS & FIGURES/PAST CHAMPS & MEDALLISTS 1 PAST CHAMPIONSHIPS –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– These totals do not include athletes entered for the championships who never started, but teams are counted -

Names Positions Countries Adriana Ospina Director of Pro Bono Partnerships Cyrus R. Vance Center for International Justice Colom

Summit - Participants Confirmed Names Positions Countries Adriana Ospina Director of Pro Bono Partnerships Cyrus R. Vance Center for International Justice Colombia Alexander Papachristou Executive Director Cyrus R. Vance Center for International Justice United States of America Álvaro Rodrigo Castellanos Partner Consortium Legal Guatemala Amy Williams Author at Latin America Goes Global United States of America Antonia Stolper Partner Shearman & Sterling United States of America Arturo Alessandri President of the Chilean Bar Association; Partner Alessandri Chile Ana Luiza Martins Partner Tauil & Chequer Advogados Associado a Mayer Brown Brazil Antonio Maldonado International Consultant Peru Bret Parker Executive Director New York City Bar Association United States of America Brian Winter Vice President, Policy, AS/COA and Editor-in-Chief, Americas Quarterly United States of America Carlos del Río Partner Creel, García-Cuéllar, Aiza y Enríquez, S.C. Mexico Carlos Ernesto González Partner Morgan & Morgan Panama Carmen Amalia Corrales Partner Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton United States of America Carmen Rosa Villa Quintana United Nations Attorney Peru Christopher Sabatini Founder and Editor Latin America Goes Global; Professor at Columbia United States of America Ciro Colombara Partner Rivadeneira Colombara Zegers; Director Fundación Pro Bono Chile Claudia Escobar Judge; Scholar at Risk at Harvard University Guatemala Clea Bowdery Staff Attorney Environment Program Cyrus R. Vance Center for International Justice United States of America -

— Olympic Games — Lachkovics 10.44; 9

■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■ Volume 46, No. 12 NEWSLETTERNEWSLETTER ■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■track October 31, 2000 II(0.3)–1. Boldon 10.11; 2. Collins 10.19; 3. Surin 10.20; 4. Gardener 10.27; 5. Williams 10.30; 6. Mayola 10.35; 7. Balcerzak 10.38; 8. — Olympic Games — Lachkovics 10.44; 9. Batangdon 10.52. III(0.8)–1. Thompson 10.04; 2. Shirvington 10.13; 3. Zakari 10.22; 4. Frater 10.23; 5. de SYDNEY, Australia, September 22–25, 10.42; 4. Tommy Kafri (Isr) 10.43; 5. Christian Lima 10.28; 6. Patros 10.33; 7. Rurak 10.38; 8. 27–October 1. Nsiah (Gha) 10.44; 6. Francesco Scuderi (Ita) Bailey 11.36. Attendance: 9/22—97,432/102,485; 9/23— 10.50; 7. Idrissa Sanou (BkF) 10.60; 8. Yous- IV(0.8)–1. Chambers 10.12; 2. Drummond 92,655/104,228; 9/24—85,806/101,772; 9/ souf Simpara (Mli) 10.82;… dnf—Ronald Pro- 10.15; 3. Ito 10.25; 4. Buckland 10.26; 5. Bous- 25—92,154/112,524; 9/27—96,127/102,844; messe (StL). sombo 10.27; 6. Tilli 10.27; 7. Quinn 10.27; 8. 9/28—89,254/106,106; 9/29—94,127/99,428; VI(0.2)–1. Greene 10.31; 2. Collins 10.39; 3. Jarrett 16.40. 9/30—105,448; 10/1—(marathon finish and Joseph Batangdon (Cmr) 10.45; 4. Andrea V(0.2)–1. Campbell 10.21; 2. C. Johnson Closing Ceremonies) 114,714. Colombo (Ita) 10.52; 5. Watson Nyambek (Mal) 10.24; 3. -

2016 Meeting Program

International Society of Exposure Science PROGRAM 2016 Annual Meeting BOOK ONE-PAGE MEETING-AT-A-GLANCE Welcome Messages - Lesa and Yuri _______________________________________________________________________________ 4 TABLE OF Time Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Time 9 October 10 October 11 October 12 October 13 October - Tim Buckley _________________________________________________________________________________ 5 Meeting-at-a-Glance CONTENTS 07.00 - 08.00 Student/ 07.00 - 08.00 New Researcher - Sunday, October 9 _______________________________________________________________________ 6 Breakfast Workhop - Monday, October 10 ____________________________________________________________________ 6 08:00 - 08:30 08:00 - 08:30 PLENARY PLENARY PLENARY - Tuesday, October 11 ____________________________________________________________________ 7 08:30 - 09:00 90 m Oral 08:30 - 09:00 - Wednesday, October 12 ______________________________________________________________ 9 - Thursday, October 13 ________________________________________________________________ 10 09:00 - 09:30 90 m Oral 90 m Oral 90 m Oral 09:00 - 09:30 ISES Organization ______________________________________________________________________________________ 11 09:30 - 10:00 09:30 - 10:00 General Information _________________________________________________________________________________ 17 Optional ISES Jaarbeurs map ___________________________________________________________________________________________ 19 Work- Board 10:00 - 10:30 POSTER VIEWING 10:00 - 10:30 shops -

La Justicia De Los Afligidos

Ed ediciones digitales Directores José Eloy Hortal Muñoz Manuel Rivero Rodríguez Eduardo Torres Corominas La enseñanza de las Humanidades y las Ciencias Sociales a través del mundo digital Selección de los mejores trabajos del MOOC Cómo escribir un texto académico en Humanidades y Ciencias Sociales humanidades # CIENCIAS SOCIALES Cine 1. La representación de la violencia en la Trilogía Corazón de Oro de Lars von Trier Inmaculada Carretero López ................................................................ 21 Periodismo 2. La cobertura mediática de la información de sucesos. El caso de Eva María Lavandeira Silvia Alende Castro ............................................................................... 37 Educación 3. Participación de las familias en la escuela desde el punto de vista de los docentes Inés Esquilas Cid .................................................................................... 48 4. “Deus não escolhe os capacitados e sim capacita os escolhidos”. Mulheres são capacitadas no pronatec/bsm mulheres mil no ifb Veronica Lima da Fonseca Almeida ....................................................... 61 Lingüística 5. A Fala dois puntu zeru: Iniciativas y movimientos socioculturales para la conservación y difusión del habla de San Martín de Trevejo, Eljas y Valverde del Fresno Carmen Álvarez González-Jubete ........................................................... 89 Turismo 6. Desarrollo del turismo rural mediante la puesta en valor de yacimientos arqueológicos: Los baños árabes de Baza Julia García González.......................................................................... -

2015 Legal Summit of the Americas Summit Report

2015 Legal Summit of the Americas Summit Report Executive Summary This report reviews and reports on the 2015 Legal Summit of the Americas, a gathering of 86 attorneys, NGO leaders and academics organized by the Vance Center at the New York City Bar Association in December 2015, with the generous support of Tinker Foundation. The report opens with a brief introduction detailing the premises and objectives of the Summit. Subtitled “The Lawyer and Democracy”, the gathering focused on how members of the legal profession collectively can confront current challenges to the rule of law and open society in the hemisphere. The Vance Center conceived of the Summit to help identify and prioritize strategic initiatives for its and its partners’ ongoing engagement in Latin America, building on the blueprints already laid out during the 2005 summit and the ensuing pro bono initiative. The report continues with a general description of the four panels in which participants appeared throughout the two-day event. These panels addressed several issues, including current economic and political conditions and pressing human rights issues in Latin America and the ethical obligation of lawyers to support access to justice and the development of pro bono practice, focused on implementing the Pro Bono Declaration of the Americas. The heart of this report recounts three working group discussions at the Summit, each focusing on a specific theme: supporting civil society; promoting honesty in governance; and enhancing ethics in the legal profession. Working group A’s participants first identified the obstacles that impair lawyers’ efforts to support civil society, and then explored and posited cross-border and national collaboration strategies to overcome these obstacles. -

2015 Media Guide

2015 Media Guide 37TH ANNUAL 10K / MEMORIAL DAY / MAY 25, 2015 / FINISHING AT Media Guide 6:55am • Monday, May 25, 2015 Contents Welcome – Race Director & Founder Cliff & Steve Bosley ................................................................................................................................... 7 1. BolderBOULDER History ...................................................................................................................................................................................................... 10-13 Numbers .................................................................................................................................................................................................. 14-16 Maps ........................................................................................................................................................................................................ 17-20 Race Statistics ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 21-29 Weather .................................................................................................................................................................................................... 30-32 BBRacers Club (formerly the Middle School Challenge) .............................................................................................................................. -

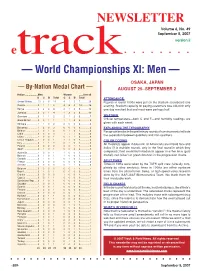

NEWSLETTER Volume 6, No

NEWSLETTER Volume 6, No. 49 September 5, 2007 version ii etrack — World Championships XI: Men — OSAKA, JAPAN — By-Nation Medal Chart — AUGUST 25–SEPTEMBER 2 Nation ..................Men Women ......Overall G S B Total G S B Total ATTENDANCE United States .......10 3 6 19 4 1 2 7 ............26 Figures in round 1000s were put on the stadium scoreboard one Russia ..................0 1 1 2 4 8 2 14 ..........16 evening. Stadium capacity for paying customers was c36,000; only Kenya ..................3 2 3 8 2 1 2 5 ............13 one day reached that and most were perhaps half. Jamaica ...............0 3 1 4 1 3 2 6 ............10 Germany ..............0 1 1 2 2 1 2 5 ..............7 WEATHER Great Britain .........0 0 1 1 1 1 2 4 ..............5 Official temperature—both C and F—and humidity readings are Ethiopia ................1 1 0 2 2 0 0 2 ..............4 given with each event. Bahamas ..............1 2 0 3 0 0 0 0 ..............3 EXPLAINING THE TYPOGRAPHY Belarus ................1 0 1 2 0 1 0 1 ..............3 Paragraph breaks in the preliminary rounds of running events indicate Cuba ....................0 0 0 0 1 1 1 3 ..............3 the separation between qualifiers and non-qualifiers. China ...................1 0 0 1 0 1 1 2 ..............3 Czech Republic ....1 0 0 1 1 1 0 2 ..............3 COLOR CODING Italy ......................0 1 1 2 0 1 0 1 ..............3 All medalists appear in blue ink; all Americans are in bold face and Poland .................0 0 2 2 0 0 1 1 ..............3 Spain ...................0 1 0 1 0 0 2 2 ..............3 italics (if in multiple rounds, only in the final round in which they Australia ...............1 0 0 1 1 0 0 1 ..............2 competed); field-event/multi medalists appear in either blue (gold Bahrain ................0 1 0 1 1 0 0 1 ..............2 medal), red (silver) or green (bronze) in the progression charts. -

EL ATLETISMO IBEROAMERICANO A.I.A Asociación Iberoamericana De Atletismo

EL ATLETISMO IBEROAMERICANO A.I.A Asociación Iberoamericana de Atletismo Realiza y Edita Real Federación Española de Atletismo Autor: Ignacio Mansilla con la colaboración especial del Comité Organizador de San Fernando’2010 Asociación Iberoamericana de Atletismo - A.I.A. Realiza y Edita: Real Federación Española de Atletismo con la colaboración especial del Comité Organizador de San Fernando’2010 Autor: Ignacio Mansilla Depósito Legal: ISBN: 84 - 87704 - 77 - 8 Impreso en España Primera edición - septiembre 1994 Segunda edición - julio 1998 Tercera edición - julio 2004 Cuarta edición - mayo 2010 ÍNDICE ÍNDICE .................................................................................................................................. 3 Agradecimientos y fuentes consultadas ........................................................................ 4 SALUDA (Presidente de la A.I.A.) .................................................................................. 5 SALUDA (Presidente del Comité Organizador)......................................................... 6 SALUDA (Presidente de la RFEA) .................................................................................. 7 INTRODUCCIÓN Creación de la Asociación Iberoamericana de Atletismo.................................. 8 Acta Fundacional de la A.I.A .................................................................................... 9 Protocolo de Fundación de la A.I.A ....................................................................... 11 Reglamento Deportivo de los Campeonatos -

World Athletics Half Marathon Championships Facts & Figures

WORLD ATHLETICS HALF MARATHON CHAMPIONSHIPS FACTS & FIGURES Incorporating the World Athletics Half Marathon Championships (1992-2005/2008-2010-2012-2014-2016-2018) World Athletics Road Running Championships 2006/2007 Past Championships...............................................................................................1 Championship Records ..........................................................................................1 Past Medallists .......................................................................................................1 Overall Placing Table..............................................................................................6 Most Medals Won...................................................................................................7 Youngest & Oldest..................................................................................................8 Most Appearances by Athlete.................................................................................8 Most Appearances by Country ...............................................................................9 Country Index .......................................................................................................11 World & Area Road Records and Best Performances .........................................43 Progression of World & Area Road Records and Best Performances ..................47 National Records and Best Performances at Half Marathon ...............................52 Doping Disqualifications at the World Athletics