Codex-Style Ceramics: New Data Concerning Patterns of Production and Distribution by Dorie Reents-Budet Dept

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CATALOG Mayan Stelaes

CATALOG Mayan Stelaes Palos Mayan Collection 1 Table of Contents Aguateca 4 Ceibal 13 Dos Pilas 20 El Baúl 23 Itsimite 27 Ixlu 29 Ixtutz 31 Jimbal 33 Kaminaljuyu 35 La Amelia 37 Piedras Negras 39 Polol 41 Quirigia 43 Tikal 45 Yaxha 56 Mayan Fragments 58 Rubbings 62 Small Sculptures 65 2 About Palos Mayan Collection The Palos Mayan Collection includes 90 reproductions of pre-Columbian stone carvings originally created by the Mayan and Pipil people traced back to 879 A.D. The Palos Mayan Collection sculptures are created by master sculptor Manuel Palos from scholar Joan W. Patten’s casts and rubbings of the original artifacts in Guatemala. Patten received official permission from the Guatemalan government to create casts and rubbings of original Mayan carvings and bequeathed her replicas to collaborator Manuel Palos. Some of the originals stelae were later stolen or destroyed, leaving Patten’s castings and rubbings as their only remaining record. These fine art-quality Maya Stelae reproductions are available for purchase by museums, universities, and private collectors through Palos Studio. You are invited to book a virtual tour or an in- person tour through [email protected] 3 Aguateca Aguateca is in the southwestern part of the Department of the Peten, Guatemala, about 15 kilometers south of the village of Sayaxche, on a ridge on the western side of Late Petexbatun. AGUATECA STELA 1 (50”x85”) A.D. 741 - Late Classic Presumed to be a ruler of Aguatecas, his head is turned in an expression of innate authority, personifying the rank implied by the symbols adorning his costume. -

Ella Smit ARTH 281 Spring, 2019 the Life-Force of Mayan Ceramics The

Ella Smit ARTH 281 Spring, 2019 The Life-Force of Mayan Ceramics The Maya civilization is a complex society with a host of ritual and aesthetic practices placed at the forefront of all mortal and supernatural relationships. This paper seeks to unpack these complexities and provide a glimpse into the proximate relationship of ceramics and spirituality. Through the research I have compiled on two Maya vessels held at the Williams College Museum of Art (WCMA)–– one bearing the iconography of an anthropomorphic coyote, and the other petals of a flower–– I will place the artistic aesthetics of these pieces in conversation with ritual practice. Ceramics provided a gateway into the realm of the mortal and supernatural, and I hope that, by and large, one is able to understand the awe-inducing influence these ritual practices leveraged on Maya society through these ceramics of the Classic period. The Classic-period Maya civilization was constructed around small to large peer polities predominantly in the Maya Lowlands in Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, and Belize.1 The Classic period spanned from 300-1000 AD and is partitioned into three distinct stages of subperiods: Early Classic, Late Classic, and Terminal Classic.2 Polity consolidation began by the Early Classic period (250-500 AD) primarily due to the intensification of a centralized agricultural system and trading economy in the hands of a priestly elite. While new townships and cities were forming rapidly in the Early Classic period, vast amounts of rural and small 1 Antonia Foias, “Maya Civilization of the Classic Period (300-1000AD), The Seeds of Divinity (ARTH 281), Spring, 2019, Williams College. -

Download/Attachments/Dandelon/Ids/ DE SUB Hamburg2083391e82e43888c12572dc00487f57.Pdf Burtner, J

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Tourism and Territory in the Mayan World Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5727x51w Author Devine, Jennifer Ann Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Tourism and Territory in the Mayan World By Jennifer Ann Devine A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction for the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Geography in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Gillian Hart, Co-Chair Professor Michael Watts, Co-Chair Professor Jake Kosek Professor Rosemary Joyce Fall 2013 Abstract Tourism and Territory in the Mayan World by Jennifer Ann Devine Doctor of Philosophy in Geography University of California, Berkeley Professor Gillian Hart, Co-Chair Professor Michael Watts, Co-Chair In post Peace Accords Guatemala, tourism development is engendering new claims and claimants to territory in a climate of land tenure insecurity and enduring inequality. Through ethnographical research, this dissertation explores the territoriality of tourism development through the empirical lens of an archaeological site called Mirador in the Maya Biosphere Reserve. I develop a process-based understanding of territoriality to analyze tourism related struggles over identity, boundary making, land use, heritage claims, and territorial rule at the frontier of state power. In theorizing tourism’s territoriality, I argue that -

Foundation for Maya Cultural and Natural Heritage

Our mission is to coordinate efforts Foundation for Maya Cultural and provide resources to identify, and Natural Heritage lead, and promote projects that protect and maintain the cultural Fundación Patrimonio Cultural y Natural Maya and natural heritage of Guatemala. 2 # nombre de sección “What is in play is immense” HSH Prince Albert II of Monaco he Maya Biosphere Reserve is located in the heart of the Selva Maya, the Maya Jungle. It is an ecological treasure that covers one fifth of Guatemala’s landmass (21,602 Tsquare kilometers). Much of the area remains intact. It was established to preserve—for present and future generations— one of the most spectacular areas of natural and cultural heritage in the world. The Maya Biosphere Reserve is Guatemala’s last stronghold for large-bodied, wide-ranging endangered species, including the jaguar, puma, tapir, and black howler monkey. It also holds the highest concentration of Maya ruins. Clockwise from bottomleft José Pivaral (President of Pacunam), Prince Albert II of Monaco (sponsor), Mel Gibson (sponsor), Richard Hansen (Director of Mirador The year 2012 marks the emblematic change of an era in the ancient calendar of the Maya. This Archaeological Project) at El Mirador momentous event has sparked global interest in environmental and cultural issues in Guatemala. After decades of hard work by archaeologists, environmentalists, biologists, epigraphers, and other scientists dedicated to understanding the ancient Maya civilization, the eyes of the whole Pacunam Overview and Objectives 2 world are now focused on our country. Maya Biosphere Reserve 4 This provides us with an unprecedented opportunity to share with the world our pressing cause: Why is it important? the Maya Biosphere Reserve is in great danger. -

War Banners: a Mesoamerican Context for the Title of Liberty Kerry Hull

Journal of Book of Mormon Studies Volume 24 | Number 1 Article 5 1-1-2015 War Banners: A Mesoamerican Context for the Title of Liberty Kerry Hull Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Hull, Kerry (2015) "War Banners: A Mesoamerican Context for the Title of Liberty," Journal of Book of Mormon Studies: Vol. 24 : No. 1 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms/vol24/iss1/5 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the All Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Book of Mormon Studies by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. War Banners: A Mesoamerican Context for the Title of Liberty Kerry Hull The making of the title of liberty in the Book of Mormon is one of the more passionate episodes in the text. Moroni, as chief commander of the Nephite forces, rallied his people to defend the most cherished aspects of Nephite culture: their families, religion, peace, and freedom. What is sometimes overlooked in this event is the heavily martial con- text in which the title of liberty appears and functions. More than sim- ply an inspirational, tangible symbol of the rights that were in jeopardy, the title of liberty was profoundly linked to warfare. In this study I place the title of liberty within a Mesoamerican context to show numerous correspondences to what we know of battle standards in Mesoamerica. Through an analysis of battle standards in the iconography and epigra- phy of ancient Mesoamerican civilizations, I argue that the title of lib- erty fits comfortably in both form and function in this well-established warfare tradition. -

Water Lily and Cosmic Serpent: Equivalent Conduits of the Maya Spirit Realm

Journal of Ethnobiology 32(1): 74–107 Spring/Summer 2012 WATER LILY AND COSMIC SERPENT: EQUIVALENT CONDUITS OF THE MAYA SPIRIT REALM J. Andrew McDonald and Brian Stross This study examines the roles of the serpent and water lily in Maya epigraphy and iconography and, from an ethnobotanical perspective, interprets these elements in Classic and post-Classic Maya images and glyphs in ways that challenge conventional wisdom. We introduce a new and testable explanation for the evident Maya perception of a close symbolic relationship between the feathered serpent and the water lily (Nymphaea ampla DC.), whereby we identify the plant’s serpentoid peduncle with ophidian images and the plant’s large-petalose (plumose) flowers with avian symbols. Physical and symbolic similarities between the Water Lily Serpent, the Water Lily Monster, the Quadripartite God, a rain/lightning deity referred to as Chahk, and the Vision Serpent are assessed with the suggestion that these entities share a closer relationship than previously suspected based in large part on their shared and overlooked water lily attributes. Our novel interpretations are presented in light of recurrent suggestions that Nymphaea ampla was employed as a psychotropic medium in religious and dynastic rituals. Key words: Nymphaea ampla, water lily serpent, feathered serpent, vision serpent, entheogen En este estudio se investiga el papel y las funciones simbo´licas de la serpiente y el lirio acua´tico (Nymphaea ampla DC.) en la epigrafı´a e iconografı´a de los Mayas pre-colombinos. Adema´s se interpretan estos elementos simbo´licos en los glifos e ima´genesdelosperiodoscla´sico y poscla´sico desde una perspectiva etnobota´nica que cuestiona su interpretacio´n convencional. -

The Realities of Looting in the Rural Villages of El Petén, Guatemala

FAMSI © 1999: Sofia Paredes Maury Surviving in the Rainforest: The Realities of Looting in the Rural Villages of El Petén, Guatemala Research Year : 1996 Culture : Maya Chronology : Contemporary Location : Petén, Guatemala Site : Tikal Table of Contents Note to the Reader Introduction Purpose, Methodology, and Logistics Geographical Setting Rainforest Products and Seasonal Campsites Who are the Looters? Magic and Folklore Related to Looting Voices in the Forest Tombs with Riches, Tombs with Magic Glossary of local words Local Knowledge about Maya Art and History Local Classification of Precolumbian Remains Local Re-Utilization of Archaeological Objects Destruction vs. Conservation. What are the Options? Cultural Education in Guatemala The Registration of Archaeological Patrimony Acknowledgements List of Figures Sources Cited Abbreviations Note to the Reader The present article is intended to be used as an informational source relating to the role of local villagers involved in the process of looting. For reasons of privacy, I have used the letters of the Greek alphabet to give certain individuals fictitious names. Words that refer to local mannerisms and places related to the topic, which are in the Spanish or Maya languages, are written in italics. The names of institutions are in Spanish as well, and abbreviations are listed at the end of the article. The map is shown below. Submitted 02/01/1997 by : Sofia Paredes Maury 2 Introduction This study was supported in part by funds from the Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, Inc. (FAMSI, Crystal River, FL). It is an introductory research that focuses on the extraction and commercialization of Precolumbian artifacts by the rural villagers of El Petén, and the role of the community and site museums in Guatemala. -

The Maize Tamale in Classic Maya Diet, Epigraphy, and Art 153

CHAPTER 5 TheMaizeTamaleinClassicMaya Diet,Epigraphy,andArt In the past decade of Classic Maya research, the study of iconography and epigraphy has not played a major role in the formulation of archaeological research designs. Site excavation and settlement reconnaissance strategies tend to focus on gathering information relevant to topics such as relative and absolute chronology, settlement patterns, technology, subsistence, and exchange. Most recent epigraphic and iconographic work has focused upon less-material aspects of culture, including calendrics, the compilation of king lists, war events, and the delineation of particular ceremonies and gods. The differences are an expected consequence of increased specialization, but they should by no means be considered as constituting a hard and fast dichotomy. Some of the most exciting and important work results from exchange between the two general disciplines; the calendar correlation problem is an obvious example. To cite this chapter: Yet another is Dennis Puleston’s (1977) work on the iconography of raised field agriculture. [1989]2018 In Studies in Ancient Mesoamerican Art and Architecture: Selected Works According to Puleston, the abundant representation of water lilies, fish, aquatic birds, and by Karl Andreas Taube, pp. 150–167. Precolumbia Mesoweb Press, San Francisco. caimans in Classic Maya art graphically depicts a distinct environmental niche—the artifi- Electronic version available: www.mesoweb.com/publications/Works cially created raised fields. A considerable body of data now exists on Maya raised fields, but little subsequent work has been published on the iconography of raised fields or even Classic Maya agriculture. In part, this may relate to Puleston’s failure to define the entire agricultural complex. -

The Ceramic Sequence of Piedras Negras, Guatemala: Type and Varieties 1

FAMSI © 2004: Arturo René Muñoz The Ceramic Sequence of Piedras Negras, Guatemala: Type and Varieties 1 Research Year : 2003 Culture : Maya Chronology : Classic Location : Northwestern Guatemala Site : Piedras Negras Table of Contents Abstract Resumen Introduction Previous Research Current Research The Sample Methods Employed in this Study Piedras Negras Chronology and Typology The Hol Ceramic Phase (500 B.C.–300 B.C.) The Abal Ceramic Phase (300 B.C.–A.D. 175) The Pom Ceramic Phase (A.D. 175–A.D. 350) The Naba Ceramic Phase (A.D. 350–A.D. 560) The Balche Ceramic Phase (A.D. 560–A.D. 620) The Yaxche Ceramic Phase (A.D. 620–A.D. 750) The Chacalhaaz Ceramic Phase (A.D. 750–A.D. 850) The Kumche Ceramic Phase (A.D. 850–A.D. 900?) The Post Classic Type List 1 This report should be taken as a supplement to the "Ceramics at Piedras Negras " report submitted to FAMSI in April of 2002. In most regards, these two reports are complementary. However, it is important to note that the initial report was posted early in the research. In cases where these reports appear contradictory, the data presented here should be taken as correct. Acknowledgements Table of Images Sources Cited Abstract Between March of 2001 and August of 2002, the ceramics excavated from the Classic Maya site Piedras Negras between 1997 and 2000 were subject of an intensive study conducted by the author and assisted by Lic. Mary Jane Acuña and Griselda Pérez of the Universidad de San Carlos in Guatemala City, Guatemala. 2 The primary goal of the analyses was to develop a revised Type:Variety classification of the Piedras Negras ceramics. -

Maya Ceramic Production and Trade: a Glimpse Into Production Practices and Politics at a Terminal Classic Coastal Maya Port

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Anthropology Honors Theses Department of Anthropology Spring 2013 Maya Ceramic Production and Trade: A Glimpse into Production Practices and Politics at a Terminal Classic Coastal Maya Port Christian Holmes Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/anthro_hontheses Recommended Citation Holmes, Christian, "Maya Ceramic Production and Trade: A Glimpse into Production Practices and Politics at a Terminal Classic Coastal Maya Port." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2013. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/anthro_hontheses/9 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Anthropology at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ! MAYA!CERAMIC!PRODUCTION!AND!TRADE:!A!GLIMPSE!INTO!PRODUCTION!PRACTICES! AND!POLITICS!AT!A!TERMINAL!CLASSIC!COASTAL!MAYA!PORT! ! ! ! ! An!Honors!Thesis! ! Submitted!in!Partial!Fulfillment!of!the! ! Requirements!for!the!Bachelor!of!Arts!DeGree!in!AnthropoloGy! ! Georgia!State!University! ! 2013! ! by Christian Michael Holmes Committee: __________________________ Dr.!Jeffrey!Barron!Glover,!Honors!Thesis!Director ______________________________ Dr.!Sarah!Cook,!Honors!ColleGe!Associate!Dean ______________________________ Date! ! ! MAYA!CERAMIC!PRODUCTION!AND!TRADE:!A!GLIMPSE!INTO!PRODUCTION!PRACTICES! AND!POLITICS!AT!A!TERMINAL!CLASSIC!COASTAL!MAYA!PORT! ! by CHRISTIAN MICHAEL HOLMES Under the Direction of Dr. Jeffrey B. Glover ABSTRACT This paper explores a particular ceramic type, Vista Alegre Striated, an assumed locally produced utilitarian cooking vessel, recovered at the coastal Maya site of Vista Alegre during the Terminal Classic period (AD 800-1100). This study investigates the variations present within this type and how these differences inform production practices at the site and in the region. -

Reflections on the Codex Style and the Princeton Vessel

ThePARIJournal A quarterly publication of the Pre-Columbian Art Research Institute Volume X, No. 1, Summer 2009 Reflections on the Codex Style and 1 the PrincetonVessel ERIK VELÁSQUEZ GARCÍA In This Issue: Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, UNAM It was early in the 1970s that the academic “codex style” to designate this group of community became aware of a number clay containers of unknown origin. Reflections on the of Maya vessels of uncertain provenance Manufacture of these ceramics has Codex Style and the that quickly came to be recognized for a been dated to AD 672-731 (Reents-Budet Princeton Vessel particular style. This was characterized et al. 1997). Based on type and variety, the by scenes and glyphic texts executed with tradition is grouped under the category by dark lines on cream-colored backgrounds, of Zacatal Cream-polychrome (Hansen et Erik Velásquez García the pictorial space usually framed by red al. 1991:225; López and Fahsen 1994:69), bands on the edges of the vessels (Fig- with a distribution in the Peten and south- PAGES 1-16 ures 1–9, 12, 14). This lent them a certain ern Campeche. Codex-style vessels are resemblance to Maya manuscripts of the characterized by the high quality of their Color version available Late Postclassic. Accordingly, Michael D. clays and firing techniques, as well as the at www.mesoweb.com/ Coe (1973: 91) conjectured that their paint- use of carbonate temper (Reents-Budet pari/journal/Codex.html ers were also the authors of the bark pa- and Bishop 1987:780, 783; Hansen et al. -

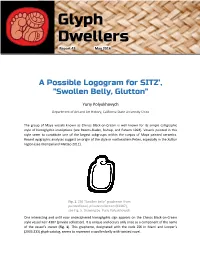

Report 43 May 2016

Glyph Dwellers Report 43 May 2016 A Possible Logogram for SITZ’, "Swollen Belly, Glutton" Yuriy Polyukhovych Department of Art and Art History, California State University Chico The group of Maya vessels known as Chinos Black-on-Cream is well known for its simple calligraphic style of hieroglyphic inscriptions (see Reents-Budet, Bishop, and Fahsen 1994). Vessels painted in this style seem to constitute one of the largest subgroups within the corpus of Maya painted ceramics. Recent epigraphic analyses suggest an origin of the style in northeastern Peten, especially in the Xultun region (see Krempel and Matteo 2011). Fig. 1. ZS6 "Swollen belly" grapheme from painted bowl, private collection (K4387), see Fig. 5. Drawing by Yuriy Polyukhovych. One interesting and until now undeciphered hieroglyphic sign appears on the Chinos Black-on-Cream style vessel Kerr 4387 (private collection). It is unique and occurs only once as a component of the name of the vessel’s owner (Fig. 1). This grapheme, designated with the code ZS6 in Macri and Looper’s (2003:233) glyph catalog, seems to represent a swollen belly with twisted navel. Glyph Dwellers Report 43 A Possible Logogram for SITZ', "Swollen Belly, Glutton" This identification is confirmed through comparison with representations of one of the wahy spirits studied by Grube and Nahm (1994). For example, vessels K927, K2286 and K2716 depict wahy spirits with distended bellies and everted, twisted navels exactly as represented by ZS6 (Figs. 2, 3, 4). The proper name of this wahy is usually spelled si-tz’i CHAM-ya, sitz’ chamay/chamiiy, "gluttony death," or si-tz’i WINIK-ki, sitz’ winik, "gluttony man" (Grube and Nahm 1994:709).