Language Conflict and Claims for the Expansion of Language Rights in Lithuania: Contrasting Cases of Polish and Russian Minorities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evolution of the Belarusian National Movement in The

EVOLUTION OF THE BELARUSIAN NATIONAL MOVEMENT IN THE PAGES OF PERIODICALS (1914-1917) By Aliaksandr Bystryk Submitted to Central European University Nationalism Studies Program In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Advisor: Professor Maria Kovacs Secondary advisor: Professor Alexei Miller CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2013 Abstract Belarusian national movement is usually characterised by its relative weakness delayed emergence and development. Being the weakest movement in the region, before the WWI, the activists of this movement mostly engaged in cultural and educational activities. However at the end of First World War Belarusian national elite actively engaged in political struggles happening in the territories of Western frontier of the Russian empire. Thus the aim of the thesis is to explain how the events and processes caused by WWI influenced the national movement. In order to accomplish this goal this thesis provides discourse and content analysis of three editions published by the Belarusian national activists: Nasha Niva (Our Field), Biełarus (The Belarusian) and Homan (The Clamour). The main findings of this paper suggest that the anticipation of dramatic social and political changes brought by the war urged national elite to foster national mobilisation through development of various organisations and structures directed to improve social cohesion within Belarusian population. Another important effect of the war was that a part of Belarusian national elite formulated certain ideas and narratives influenced by conditions of Ober-Ost which later became an integral part of Belarusian national ideology. CEU eTD Collection i Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1. Between krajowość and West-Russianism: The Development of the Belarusian National Movement Prior to WWI ..................................................................................................... -

S E M I N a R Use of Fresh Groundwater for Drinking Water Supply of Population in Emergency Situations

IUGS-GEM Commission on Geoscience for Environmental Management S E M I N A R Use of Fresh Groundwater for Drinking Water Supply of Population in Emergency situations Field trip guide 2015 June 3–5 History of water supply in Vilnius – from springs Vilnius, Lithuania to centralized systems S E M I N A R Use of Fresh Groundwater for Drinking Water Supply of Population in Emergency situations FIELD TRIP GUIDE History of water supply in Vilnius – from springs to centralized systems 2015 June 3–5 Vilnius, Lithuania FIELD TRIP GUIDE Seminar „Use of Fresh Groundwater for Drinking Water Supply of Population in Emergency situations“, 2015, June 3–5, Vilnius, Lithuania: Field Trip Guide: History of water supply in Vilnius – from springs to centralized systems / Compiled by: Satkūnas J.; Lithuanian Geological Survey. – Vilnius: LGT, 2015. – 27 (1) p.: iliustr. – Bibliogr. str. gale ORGANISED BY: Lithuanian Geological Survey (LGT) Vilnius University, Faculty of Natural Sciences IUGS-GEM EuroGeoSurveys Published by Lithuanian Geological Survey Compiled by: Jonas Satkūnas Layout: Indrė Virbickienė © Lietuvos geologijos tarnyba Vilnius, 2015 2 FIELD TRIP GUIDE The Working Group on Drinking Water of the IUGS-GEM Commission Leader Prof. I. Zektser SEMINAR Use of Fresh Groundwater for Drinking Water Supply of Population in Emergency situations DATE: June 3–5, 2015 WORKSHOP VENUE: Vilnius University, Faculty of Natural Sciences. M. K. Čiurlionio str. 21/27, Vilnius, Lithuania WORKSHOP LANGUAGES: English, Russian P R O G R A M M E June 3. Arrival, informal meeting, ice-break party (16.00 h) June 4. Agenda: 9.30 – Opening by Prof. -

Lithuania Guidebook

LITHUANIA PREFACE What a tiny drop of amber is my country, a transparent golden crystal by the sea. -S. Neris Lithuania, a small and beautiful country on the coast of the Baltic Sea, has often inspired artists. From poets to amber jewelers, painters to musicians, and composers to basketball champions — Lithuania has them all. Ancient legends and modern ideas coexist in this green and vibrant land. Lithuania is strategically located as the eastern boundary of the European Union with the Commonwealth of Independent States. It sits astride both sea and land routes connecting North to South and East to West. The uniqueness of its location is revealed in the variety of architecture, history, art, folk tales, local crafts, and even the restaurants of the capital city, Vilnius. Lithuania was the last European country to embrace Roman Catholicism and has one of the oldest living languages on earth. Foreign and local investment is modernizing the face of the country, but the diverse cultural life still includes folk song festivals, outdoor markets, and mid- summer celebrations as well as opera, ballet and drama. This blend of traditional with a strong desire to become part of the new community of nations in Europe makes Lithuania a truly vibrant and exciting place to live. Occasionally contradictory, Lithuania is always interesting. You will sense the history around you and see history in the making as you enjoy a stay in this unique and unforgettable country. AREA, GEOGRAPHY, AND CLIMATE Lithuania, covering an area of 26,173 square miles, is the largest of the three Baltic States, slightly larger than West Virginia. -

Recreational Fishing in the Baltic Sea Region

PROTECTING THE BALTIC SEA ENVIRONMENT - WWW.CCB.SE RECREATIONAL FISHING IN THE BALTIC SEA REGION Coalition Clean Baltic Researched and written by Niki Sporrong for Coalition Clean Baltic E-mail: [email protected] Address: Östra Ågatan 53, 753 22 Uppsala, Sweden www.ccb.se © Coalition Clean Baltic 2017 With the contribution of the LIFE financial instrument of the European Community and the Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management Contents Background ...................................................................................................................4 Introduction ..................................................................................................................5 Summary .......................................................................................................................6 Terminology .................................................................................................................12 Finland (not including Åland1) .....................................................................................15 Estonia ..........................................................................................................................23 Latvia ............................................................................................................................32 Lithuania ......................................................................................................................39 Russia (Kaliningrad region) ..........................................................................................45 -

Vilnius University

VILNIUS UNIVERSITY E.MA Director Prof. Dainius Žalimas, Head of the Institute of International and the European Union Law, Law Faculty Websites: Fields of competence: Public International Law, International Humanitarian Law, www.tf.vu.lt/en Law of International Organizations, Human Rights Law. www.tspmi.vu.lt/en/ Other academics involved in E.MA 2011/2012 Lecturer Dr. Vygant ė Milaši ūtė, Dr. Indr ė Isokait ė Department: The university and the city Law Vilnius - the Capital of Lithuania As the capital of the Republic of Lithuania, Vilnius is an administrative, cultural, political and business center. About one seventh of the country’s population Contact persons: (approximately 600,000 people) lives here. The city was found in 1323. The Old Town, situated in a picturesque valley of two rivers – the Vilnia and the Neris, is Prof. Dainius Žalimas the heart of the capital, the oldest and architecturally the richest part of Vilnius. It E.MA Director is one of the largest old town centers in Europe and it was declared a World Room 313. Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1994. Vilnius is home to people of different ethnic Sauletekio av. 9, I backgrounds and religions. building, Vilnius For more information: http://www.vilnius.lt/index.php?2976595810 and LT10222 http://www.slideshare.net/VilniausSavivaldybe/vilnius-the-capital-of-lithuania Lithuania Vilnius University Tel. +37052366166 The University of Vilnius – is one of the oldest and most famous establishments of Fax +37052366163 higher education in Eastern and Central Europe. It was founded in 1579 when King Email: Stephen Bathory's charter transformed the Jesuit college into an establishment of [email protected] higher education, Academia et Universitas Vilnensis Societatis Jesu, the transformation being confirmed by Pope Gregory XIII. -

Report of the Joint World Heritage Centre / ICOMOS Advisory Mission to the World Heritage Property Vilnius Historic Centre, Lith

Report of the joint World Heritage Centre / ICOMOS Advisory Mission to the World Heritage property Vilnius Historic Centre, Lithuania (C 541bis) 20th to 24th November 2017 Cover: View across the missionary monastery gardens and the east side of the city, from Subačiaus Street to the 'architectural hill' This report is jointly prepared by the mission members: Ms Burcu Ozdemir (UNESCO World Heritage Centre) and Mr Paul Drury (ICOMOS). 2 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...................................................................................................................... 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................................. 5 1. BACKGROUND TO THE MISSION ........................................................................................... 8 2. NATIONAL AND LOCAL POLICY FOR PRESERVATION AND MANAGEMENT ...... 9 3. ASSESSMENT OF ISSUES .............................................................................................................. 10 3.1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 10 3.2. The Missionary Monastery ........................................................................................................ 10 3.3. High-rise buildings in the buffer zone ...................................................................................... 21 4. ASSESSMENT OF THE STATE OF CONSERVATION OF THE PROPERTY .................. 24 4.1. The fabric of the city ................................................................................................................ -

8-13 Belarus and Belarusians

Belarus and its Neighbors: Historical Perceptions and Political Constructs BelarusBelarus andand itsits Neighbors:Neighbors: HistoricalHistorical PerceptionsPerceptions andand PoliticalPolitical ConstructsConstructs InternationalInternational ConferenceConference PapersPapers EDITED BY ALEŚ Ł AHVINIEC TACIANA Č ULICKAJA WARSAW 2013 Editors: Aleś Łahviniec, Taciana Čulickaja Project manager: Anna Grudzińska Papers of the conference “Belarus and its Neighbors: Historical Perceptions and Political Constructs”. The conference was held on 9–11 of December 2011 in Warsaw, Poland. The conference was sponsored by Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung Belarus Office, National Endowment for Democracy and Open Society Institute. Translation: Vieranika Mazurkievič Proof-reading: Nadzieja Šakun (Belarusian), Katie Morris (English), Adrianna Stansbury (English) Cover design: Małgorzata Butkiewicz Publication of this volume was made possible by National Endowment for Democracy. © Copyright by Uczelnia Łazarskiego, Warsaw 2013 Oficyna Wydawnicza Uczelni Łazarskiego 02-662 Warszawa ul. Świeradowska 43 tel. 22 54-35-450, 22 54-35-410 [email protected] www.lazarski.pl ISBN: 978-83-60694-49-7 OPEN SOCIETY FOUNDATIONS Implementation of publishing: Dom Wydawniczy ELIPSA ul. Infl ancka 15/198, 00-189 Warszawa tel./fax 22 635 03 01, 22 635 17 85 e-mail: [email protected], www.elipsa.pl Contents Foreword ...................................................................................................... 7 Andrzej Sulima-Kamiński – Quo Vadis, Belarus? Instead of an -

The Polish Minority in Lithuania

a n F P 7 - SSH collaborative research project [2008 - 2 0 1 1 ] w w w . e n r i - e a s t . n e t Interplay of European, National and Regional Identities: Nations between States along the New Eastern Borders of the European Union Series of project research reports Contextual and empirical reports on ethnic minorities in Central and Eastern Europe Belarus Research Report #8 Germany The Polish Minority Hungary in Lithuania Latvia Authors: Arvydas Matulionis | Vida Beresnevičiūtė Lithuania Tadas Leončikas | Monika Frėjutė-Rakauskienė Kristina Šliavaitė | Irena Šutinienė Poland Viktorija Žilinskaitė | Hans-Georg Heinrich Russia Olga Alekseeva Slovakia Series Editors: Ukraine Hans-Georg Heinrich | Alexander Chvorostov Project primarily funded under FP7-SSH programme Project host and coordinator EUROPEAN COMMISSION www.ihs.ac.at European Research Area 2 ENRI - E a s t R es e a r c h Report #8: The Polish Minority in Lithuania About the ENRI-East research project (www.enri-east.net) The Interplay of European, National and Regional Identities: Nations between states along the new eastern borders of the European Union (ENRI-East) ENRI-East is a research project implemented in 2008-2011 and primarily funded by the European Commission under the Seventh Framework Program. This international and inter-disciplinary study is aimed at a deeper understanding of the ways in which the modern European identities and regional cultures are formed and inter-communicated in the Eastern part of the European continent. ENRI-East is a response to the shortcomings of previous research: it is the first large-scale comparative project which uses a sophisticated toolkit of various empirical methods and is based on a process-oriented theoretical approach which places empirical research into a broader historical framework. -

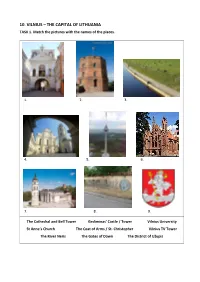

10. Vilnius – the Capital of Lithuania Task 1

10. VILNIUS – THE CAPITAL OF LITHUANIA TASK 1. Match the pictures with the names of the places. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. The Cathedral and Bell Tower Gediminas' Castle / Tower Vilnius University St Anne’s Church The Coat of Arms / St. Christopher Vilnius TV Tower The River Neris The Gates of Dawn The District of Užupis TASK 2. Do the quiz on Vilnius. 1. What is the population of Vilnius? 2. In which century / when was Vilnius founded? 3. Who is considered to be the founder of Vilnius? 4. What is the name of the river from which Vilnius takes its name? 5. What is the name of the main square of Vilnius? 6. How many churches are there in Vilnius? 7. What is the architectural style of St. Anne’s church? 8. What is the architectural style of the Town Hall? 9. Which church is often called “a Baroque pearl”? 10. Which is the oldest church in Vilnius? 11. Vilnius University is one of the oldest universities in Europe. When was it founded? 12. Which is older – Vilnius University or Vilnius University Library? 13. What is the name of the Patron Saint of Vilnius? 14. When was the Old Town of Vilnius included in the UNESCO World Heritage List? 15. In which year was Vilnius the European capital of culture? 16. What is the height of Vilnius TV tower? 17. In which month / when is the annual arts and crafts fair ('Kaziukas' fair') held in Vilnius? 18. How often is Vilnius Book Fair held? 19. -

The Lithuanian-Polish Dispute and the Great Powers, 1918-1923 Peter Ernest Baltutis

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Honors Theses Student Research 2001 The Lithuanian-Polish dispute and the great Powers, 1918-1923 Peter Ernest Baltutis Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Baltutis, Peter Ernest, "The Lithuanian-Polish dispute and the great Powers, 1918-1923" (2001). Honors Theses. 1045. https://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses/1045 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF RICHMOND LIBRARIES 1111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 3 3082 00802 6071 r UNIVERSITY OF RICHMOND THE LITHUANIAN-POLISH DISPUTE AND THE GREAT POWERS, 1918-1923 AN HONORS THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY PETER ERNEST BALTUTIS RICHMOND, VIRGINIA 04MAY2001 The Lithuanian-Polish Dispute and the Great Powers, 1918-1923 In the wake of World War I, Europe was a political nightmare. Although the Armistice of 1918 effectively ended the Great War, peace in Eastern Europe was far from assured. The sudden, unexpected end of the war, combined with the growing threat of communist revolution throughout Europe created an unsettling atmosphere during the interwar period. The Great Powers-the victorious Allied forces of France, Great Britain, Italy, and the United States-met at Paris to reconstruct Europe. In particular, the Great Powers had numerous territorial questions to resolve. -

The Iron Wolf: Lithuanian Fascism (1927-1941)

Journal of the International Students of History Association Vol. X January 2003 ISHA News Issues 40-41 Human rights through History Fascist Movements in the Baltic States I: The Iron Wolf: Lithuanian Fascism (1927-1941) The Romanian Countries during the Middle Ages, between Byzantium and West. From adventures to tourism: Conquering Slovene mountains The Uses of Microhistory Rome in the imperial idea of the 14th century: The age of Lewis the Bavarian • Index • Editorial • News o Officials • Activity o Seminarbericht Dubrovnik • Articles o The conquest of the Mountains. From Adventurism to Tourism in Slovenia o The Iron Wolf: Lithuanian Fascism (1927-1941) o The Uses of Microhistory th o Rome in the Imperial Idea of the 14 Century o The Romanian Countries during the Middle Ages • Upcoming events o AB-Meeting Berlin o Annual Conference in Helsinki • Recruitment information • Guidelines for Carnival Contributors Carnival – Journal of the International Students of History Association (IISN 1582-3261) is an international publication of the International Students of History Association (ISHA). During the academic year 2002-2003 the editorial team is located at the university of Heidelberg, Germany. Printed at the Ars Docendi Publishing House (Universitiy of Bucharest). Edition: 300 Web edition: http::/www.geocities.com/carnival_isha Editorial Team (Heidelberg) Head: Thomas Foerster Language Consultants: Alan Götz, Caroline Hesch Cover, layout and page design: Claudia Kölbl, Johan Grußendorf, Thomas Foerster Web edition: Claudia Kölbl Contact: [email protected] ISHA Contact: John Blake, President [email protected] E-mail Forum: [email protected] Join at http://www.egroups.com/group/isha-list Web pages: http://www.isha-international.org Editorial When I agreed - during the Legislative Assembly that took place at the Annual Conference in Nijmegen - to undertake the editing of Carnival for the academic year 2002/03, I was asked whether I actually knew what I was doing. -

Lithuanian National Report on Salmon by Vytautas Kesminas VU Institute of Ecology INTRODUCTION

Lithuanian National Report on Salmon by Vytautas Kesminas VU Institute of Ecology INTRODUCTION • Monitoring and restoration works of salmon and sea-trout have been carried out in accordance with Lithuanian Salmon Action Plan, 1997 – 2010 • Monitoring took place in 80 rivers inhabited by salmonids, 100-110 sites • Responsible institutions are Institute of Ecology of Vilnius University and University of Klaipėda Lithuanian Salmon and Sea-trout restoration and protection program for 1997-2010 • Action plan: • Juridical – institutional regulation, • Protection of migration ways and spawning places, • Restoration of natural spawning places, • Scientific research and monitoring, • Artificial rearing, • Education and teaching. Material and methods • Monitoring of smolt migration. Lower reaches of Mera, Siesartis and Veiviržas rivers • Monitoring of parr abundance of salmonids. Electrofishing (Zippin, 1958; Seber, Le Cren, 1967; Bohlin et al., 1977; Junge & Libosvarsky, 1965; Guidelines.., 1997) • Monitoring of spawning nests. Žeimena, Mera, Vilnia, Upper Minija, Veiviržas, Šalpė rivers Material and methods • Telemetry study • Tagging study • Genetic study • Migration of salmon and sea-trout (CPUE) into the Nemunas river basin aa B B B B B B B B B B e B e B B e B B e B e B e B ee B ee B ee B e B e B ee B B B ee B B e B B e B B e B B B B B B B Šv B B Šv B B Šv B B Šv B Šv B ŠvŠv B SS ŠvŠvŠveeentnntntttojojoj B toj a tojoj a c tojoj a c tt a c toji a i a c tojoj a c i a cc tojoj a c a cc tojii a cc i a c oji a cc tojoji a cc i a cc tojoji (B a c