"L. Ron Hubbard, How Much Is a Religious Service Worth, and Do

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Tipping” to Private Foundation Status

EOTJ-18-05-cover.qxp_Layout 1 8/14/18 9:14 AM Page 1 September/October 2018 “Tipping” to Private Foundation Status Constitutionality of Religion Code Sections Impermissible Private Benefit EOTJcoverads.qxp_Journal covers 8/16/18 11:48 AM Page 2 EOTJ-18-09-01-TOC.qxp_PTS-06-06-000-MH&TOC 8/16/18 11:51 AM Page 1 September/October 2018 Volume 30, No. 2 ARTICLES FROM PUBLIC CHARITY TO PRIVATE FOUNDATION: HOW TO HANDLE THE “TIPPING” PROBLEM 3 CHRISTOPHER M. HAMMOND RELIGIOUS ORGANIZATIONS— CONSTITUTIONALITY OF CODE PROVISIONS 17 BRUCE R. HOPKINS IDENTIFYING AND NAVIGATING IMPERMISSIBLE PRIVATE BENEFIT IN PRACTICE 26 JOHN TYLER, EDWARD DIENER, AND HILLARY BOUNDS TENANT IMPROVEMENT ALLOWANCES PAID TO EXEMPT ORGANIZATIONS 33 RICHARD A. NEWMAN THE DISAPPEARING 60% DEDUCTION— NEW CHARITABLE GIVING LIMITS ARE NOT AS GENEROUS AS THEY APPEAR 36 BRAD BEDINGFIELD AND NANCY DEMPZE THE “SIMPLE” PRIVATE FOUNDATION— CHANGING ONE LIFE AT A TIME 42 JOHN DEDON EOTJ-18-09-01-TOC.qxp_PTS-06-06-000-MH&TOC 8/16/18 11:51 AM Page 2 Editors-in-Chief Editorial Staff Joseph E. Lundy Sharon W. Nokes Managing Editor Schnader Harrison Segal & Lewis The Pew Charitable Trusts Daniel E. Feld, J.D. Philadelphia, PA Washington, DC [email protected] Director, International Board of Advisors Tax & Journals Robert Gallagher, J.D., CPA Ronald Aucutt Barbara L. Kirschten McGuire Woods, LLP Wilmer, Cutler & Pickering Desktop Artist McLean, VA Washington, DC Anthony Kibort Wendell R. Bird James J. Knicely Cover Design Bird & Loechl Knicely & Associates Christiane Bezerra Atlanta, GA Williamsburg, VA VP, Editorial, Milton Cerny Michael S. -

Colour, Screen, Read Only (Unsuitable for Print) (CS, Colour, Screen Compiled 7

DDEETTOOXX Colour, Screen, read only (unsuitable for print) (CS, Colour, Screen Compiled 7. September 2018 DETOX II 07.09.18 a) Table of Contents, in Checksheet order: 1. 68-08-28 DRUGS..........................................................................................................................................1 2. 68-08-29 DRUG DATA..................................................................................................................................3 3. 69-10-17 DRUGS, ASPIRIN AND TRANQUILIZERS....................................................................................5 4. 80-10-11 DRUGS AND THEIR EFFECTS ON AUDITING GAINS................................................................9 5. 78-02-06 THE PURIFICATION RUNDOWN REPLACES THE SWEAT PROGRAM ..................................19 6. 78-02-06 THE PURIFICATION RUNDOWN – ERRATA AND ADDITIONS ...............................................41 7. 80-05-21 PURIFICATION RUNDOWN CASE DATA ..................................................................................45 8. 80-01-03 PURIFICATION RUNDOWN AND ATOMIC WAR.......................................................................65 DETOX III 07.09.18 DETOX IV 07.09.18 b) Table of Contents, in chronological order: 1. 68-08-28 DRUGS..........................................................................................................................................1 2. 68-08-29 DRUG DATA..................................................................................................................................3 -

Edge 2012 Believer

RADAR Oxford Brookes University – Research Archive and Digital Asset Repository (RADAR) Edge, P Believer beware: the challenges of commercial religion Edge, P (2012) Believer beware: the challenges of commercial religion. Legal Studies, 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1748-121X.2012.00252.x This version is available: https://radar.brookes.ac.uk/radar/items/6590f97d-7ced-17b3-ffd0-9b2596d14303/1/ Available in the RADAR: October 2012 Copyright © and Moral Rights are retained by the author(s) and/ or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This item cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. This document is the preprint version of the journal article. Some differences between the published version and this version may remain and you are advised to consult the published version if you wish to cite from it. go/radar www.brookes.ac.uk/ Directorate of Learning Resources Applied Study of Law and Religion Group . School of Law. Believer beware. The challenges of commercial religion. Professor Peter W Edge, Oxford Brookes University, [email protected] Forthcoming, Legal Studies. For further information: Email the author: [email protected] View his profile: http://www.brookes.ac.uk/profiles/staff/peter_edge Introduction. In this paper I will argue that in a wide range of circumstances religious activity and commercial activity may overlap, leading to what may fairly, albeit novelly, be categorised as commercial religion. -

Corporate Sponsorship in Transactional Perspective: General Principles and Special Cases in the Law of Tax Exempt Organizations Frances R

University of Miami Law School University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository University of Miami Entertainment & Sports Law Review 7-1-1996 Corporate Sponsorship in Transactional Perspective: General Principles and Special Cases in the Law of Tax Exempt Organizations Frances R. Hill University of Miami School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.law.miami.edu/umeslr Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons Recommended Citation Frances R. Hill, Corporate Sponsorship in Transactional Perspective: General Principles and Special Cases in the Law of Tax Exempt Organizations, 13 U. Miami Ent. & Sports L. Rev. 5 (1996) Available at: http://repository.law.miami.edu/umeslr/vol13/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Miami Entertainment & Sports Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hill: Corporate Sponsorship in Transactional Perspective: General Princ ARTICLES CORPORATE SPONSORSHIP IN TRANSACTIONAL PERSPECTIVE: GENERAL PRINCIPLES AND SPECIAL CASES IN THE LAW OF TAX EXEMPT ORGANIZATIONS FRANCES R. HILL* Exempt organizations depend on financial support from cor- porate contributors.' Many corporations regard charitable contri- butions as an element of corporate citizenship,2 and tax law provides that corporate contributors may deduct their charitable * Associate Professor, University of Miami School of Law. The author wishes to thank Professor Elliott Manning for his helpful comments. This research was supported by a University of Miami School of Law Summer Research Grant. -

Scientology in Court: a Comparative Analysis and Some Thoughts on Selected Issues in Law and Religion

DePaul Law Review Volume 47 Issue 1 Fall 1997 Article 4 Scientology in Court: A Comparative Analysis and Some Thoughts on Selected Issues in Law and Religion Paul Horwitz Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review Recommended Citation Paul Horwitz, Scientology in Court: A Comparative Analysis and Some Thoughts on Selected Issues in Law and Religion, 47 DePaul L. Rev. 85 (1997) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review/vol47/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Law Review by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SCIENTOLOGY IN COURT: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS AND SOME THOUGHTS ON SELECTED ISSUES IN LAW AND RELIGION Paul Horwitz* INTRODUCTION ................................................. 86 I. THE CHURCH OF SCIENTOLOGY ........................ 89 A . D ianetics ............................................ 89 B . Scientology .......................................... 93 C. Scientology Doctrines and Practices ................. 95 II. SCIENTOLOGY AT THE HANDS OF THE STATE: A COMPARATIVE LOOK ................................. 102 A . United States ........................................ 102 B . England ............................................. 110 C . A ustralia ............................................ 115 D . Germ any ............................................ 118 III. DEFINING RELIGION IN AN AGE OF PLURALISM -

Re: Church of Scientology When We Last Met on 20 April You Noted That

195 Re: Church of Scientology When we last met on 20 April you noted that you had seen press releases about two recent court cases in Germany involving Churches of Scientology located there. Apparently, these press reports indicated that the two court decisions ruled that Scientology is not a religion. You asked for our comments on the two decisions. One such court decision involves the appliqability -ofetreade- registration laws to the Church of Scientology -of Hamle4r4,e This decision simply holds that the Church, because-of its activities; was required to comply with the relevant trade registration laws whether or not the organisation in question happens to bo a church or another religious organisation. Thus, this decision does not rele on Scientology's religiosity; to the contrary, - ,it proceeds from the assumption that Scientology is a religion. A copy of this decision, in both original German and Emglieh translation, is attached as Exhibit 1. It is impossible to analyze the other,00urt deciSion at this time, however, since as yet we have only t_he: Press - rele40 And no written decision has been issued. The generAleconteXt'of this case involved the applicability of certainjabour Yaws tO the Church of Scientology of Hamburg. It may well be that the written decision, once released, will be the same as the first Hamburg case -- a determination that the relevant laws apply CORRESPONDENT OFFICES: LONDON. PARIS AND BRUSSELS irrespective of the religious nature of the organisation in question. On the other hand, the language of the press release suggests the appellate court in fact may have evaluated the religious character of Scientology based on independent readings of Scientology Scripture that the judges may have undertaken on their own initiative and reached a negative conclusion. -

The Descent of the Dove

Charles Williams The Descent of the Dove A short history of the Holy pirit in the church (First published 1939 by Longmans Green & Company) 4 1 Preface My first intention for the title of this book was A History of Chris- tendom : it was changed lest any reader should be misled. It is open to any reader to complain that many names, of persons and events, which have been of immense importance to Christendom, have been omitted. THE DESCENT OF THE DOVE But though they have been important their omission here is unimportant. It was inevitable that this particular book should talk about Dante and not Charles Williams, who was born in 1886 and died in about Descartes, since its special themes are found much more in Dante 1945, was a writer of unusual genius in several than in Descartes. Nevertheless, I hope the curve of history has been literary forms, as well as a brilliant conversationalist justly followed, as I hope and believe that all the dates and details are and lecturer, recognised at Oxford by an honorary accurate. If I have made a mistake anywhere, it is not for want of refer- M.A. in 1943. Educated at St. Alban’s School and ence to the specialists, but from the mere stupidity of human nature. An University College, London, he was for most of his effort has been made to keep proportion; the final modern chapter has not life a reader and literary adviser to the Oxford been allowed to run away with the book. A motto which might have been University Press; during these years he also produced set on the title-page but has been, less ostentatiously, put here instead, is a over thirty volumes of poems, plays, literary phrase which I once supposed to come from Augustine, but I am in- criticism, fiction, biography and theological argument. -

Realizing the Concept of ... Price.Pdf

REALIZING THE CONCEPT OF JUST PRICE KRATAGYA DIXIT REALIZING THE CONCEPT OF JUST PRICE by Kratagya Dixit Student number: 4812107 Master thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Management of Technology Faculty of Technology, Policy and Management Delft University of Technology To be defended in public on January 26th 2021 Graduation committee Chairperson. : Prof. dr. C.P. van Beers, Economics of Technology and Innovation First Supervisor : Dr. C.W.M. Naastepad, Economics of Technology and Innovation Second Supervisor : Dr. ir. U. Pesch, Ethics/Philosophy of Technology 1 PREFACE I want to thank Dr. C.W.M Naastepad for guiding me through this journey, and most importantly introducing me to a branch of knowledge that I greatly enjoyed exploring. A special thank you to Dr. Ir. U. Pesch and Prof. Dr. C.P. van Beers for their valuable comments and insights which helped me improve my thesis. I would also like to extend my gratitude to Ester Pendavingh for the inspiring interview and sharing her vision with me. I want to express my gratitude to my family and my friends for supporting me throughout the process. I am blessed to have you all by my side and so close to my heart. The countless conversations I had with all of you during this process not only provided me with new insights but also motivated me to keep moving forward. I pursued the topic of this thesis not just to fulfil my graduation requirement but to also contribute to the existing knowledge which I believe can have a positive impact on everyone in our society. -

Writ of Prohibition Or, in the Alternative, A

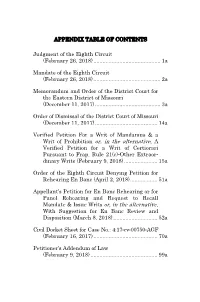

APPENDIX TABLE OF CONTENTS Judgment of the Eighth Circuit (February 26, 2018) ............................................ 1a Mandate of the Eighth Circuit (February 26, 2018) ............................................ 2a Memorandum and Order of the District Court for the Eastern District of Missouri (December 11, 2017) ........................................... 3a Order of Dismissal of the District Court of Missouri (December 11, 2017) ......................................... 14a Verified Petition For a Writ of Mandamus & a Writ of Prohibition or, in the alternative, A Verified Petition for a Writ of Certiorari Pursuant to Frap, Rule 21(c)-Other Extraor- dinary Writs (February 9, 2018) ...................... 15a Order of the Eighth Circuit Denying Petition for Rehearing En Banc (April 2, 2018) .................. 51a Appellant’s Petition for En Banc Rehearing or for Panel Rehearing and Request to Recall Mandate & Issue Writs or, in the alternative, With Suggestion for En Banc Review and Disposition (March 8, 2018) ............................. 52a Civil Docket Sheet for Case No.: 4:17-cv-00750-AGF (February 16, 2017) .......................................... 70a Petitioner’s Addendum of Law (February 9, 2018) ............................................ 99a APPENDIX TABLE OF CONTENTS (Cont.) Plaintiff’s Exhibits to Original Verified Complaint for Declaratory Judgement, Injunctive and Other Appropriate Relief in This Petition for Quintessential Rights of the First Amendment (February 16, 2017) ....................................... -

Redefining Beijing Consensus: Ten General Principles

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Li, Xin; Brødsgaard, Kjeld Erik; Jacobsen, Michael Working Paper Redefining Beijing Consensus: Ten general principles Copenhagen Discussion Papers, No. 2009-29 Provided in Cooperation with: Asia Research Community (ARC), Copenhagen Business School (CBS) Suggested Citation: Li, Xin; Brødsgaard, Kjeld Erik; Jacobsen, Michael (2009) : Redefining Beijing Consensus: Ten general principles, Copenhagen Discussion Papers, No. 2009-29, Copenhagen Business School (CBS), Asia Research Centre (ARC), Frederiksberg, http://hdl.handle.net/10398/7830 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/208628 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ www.econstor.eu 29 2009 July Redefining Beijing Consensus: Ten general principles Xin Li Kjeld Erik Brødsgaard Michael Jacobsen ©Copyright is held by the author or authors of each Discussion Paper. -

Deductibility of Mandatory Donations to Religious Organizations Under the Internal Revenue Code Sandra Machan

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron Akron Tax Journal Akron Law Journals 1990 Deductibility of Mandatory Donations to Religious Organizations Under the Internal Revenue Code Sandra Machan Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Follow this and additional works at: https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akrontaxjournal Part of the Religion Law Commons, and the Tax Law Commons Recommended Citation Machan, Sandra (1990) "Deductibility of Mandatory Donations to Religious Organizations Under the Internal Revenue Code," Akron Tax Journal: Vol. 7 , Article 7. Available at: https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akrontaxjournal/vol7/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Akron Law Journals at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The nivU ersity of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Akron Tax Journal by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Machan: Mandatory Donations DEDUCTIBILITY OF MANDATORY DONATIONS TO RELIGIOUS ORGANIZATIONS UNDER THE INTERNAL REVENUE CODE I. INTRODUCTION Church of Scientology members discovered their "inner selves" through "auditing" I and studied Church doctrines and tenets during "training" sessions.' To participate in the auditing and training sessions, members paid mandatory or 3 fixed fees to the Church. In a recent United States Supreme Court Case, the Court considered whether the mandatory donations made to the Church of Scientology constituted a charitable deduction.' The Court determined that the members made the mandatory donations with the expectation of a commensurate return benefit (i.e., a quid pro quo). -

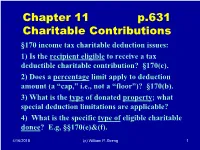

Chapter 11 P.631 Charitable Contributions

Chapter 11 p.631 Charitable Contributions §170 income tax charitable deduction issues: 1) Is the recipient eligible to receive a tax deductible charitable contribution? §170(c). 2) Does a percentage limit apply to deduction amount (a “cap,” i.e., not a “floor”)? §170(b). 3) What is the type of donated property; what special deduction limitations are applicable? 4) What is the specific type of eligible charitable donee? E.g, §§170(e)&(f). 4/16/2018 (c) William P. Streng 1 Charitable Contribution Deduction Mechanics Percentage limits on charitable deduction: 1) 50% of the “contributions base” when public charities are recipients. §170(b)(1)(A). (60% for cash contributions until 2026 – TCJA). 2) 30% (or a lesser percentage) when contribution is to a “private foundation.” 3) Corporations -10% of taxable income limit? These limits are “ceilings” and not “floors.” No “floor” is applicable to the charitable 4/16/2018contributions deduction(c) William (cf.,P. Streng casualty loss). 2 Charitable Contribution Deduction – Appropriate? Is the charitable contribution really a consumption item for FIT purposes? Is the charitable contribution deduction a substitute for direct government support? Other reasons to support a charitable contributions federal income tax deduction? - To circumvent U.S. Constitutional concerns? - To facilitate wealth distribution? A tax expenditure item? See chart (p. 536-7). 4/16/2018 (c) William P. Streng 3 Qualified Organizations? Regan v. TWR p.631 IRS determines whether an organization is entitled to §501(c)(3) tax-exempt status. Should an organization be permitted §501(c)(3) status if it attempts to influence legislation? Does denial of status violate the 1st Amendment? Decision by U.S.