Culture and Architecture 15 CHAPTER THREE Colloquial Architecture 25

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Best Local Scene in Salzburg"

"Best Local Scene in Salzburg" Gecreëerd door : Cityseeker 4 Locaties in uw favorieten Old Town (Altstadt) "Old Town Salzburg" The historic nerve center of Salzburg, the Altstadt is an enchanting district that spans 236 hectares (583.16 acres). The locale's narrow cobblestone streets conceal an entire constellation of breathtaking heritage sites and architectural marvels that showcase Salsburg's vibrant past. Some of the area's prime attractions include the Salzburg Cathedral, Collegiate by Public Domain Church, Franciscan Church, Holy Trinity Church, Nonnberg Abbey, and Mozart's birthplace. +43 662 88 9870 (Tourist Information) Getreidegasse, Salzburg Getreidegasse "Salzburg's Most Famous Shopping Street" Salzburg's Getreidegasse is the most famous street in the city, therefore the most crowded. If you are really interested in getting a view of the charming old houses, try to visit early, preferably before 10 in the morning - pretty portals and wonderful courtyards can only be seen and appreciated then. The Getreidegasse is famous for its wrought-iron signs, by Edwin Lee dating from the 16th to the 19th centuries - the design of the signs dates back to the Middle Ages! It is worth taking a second look at the houses because they are adorned with dates, symbols or the names of their owners, so they often tell their own history. +43 662 8 8987 [email protected] Getreidegasse, Salzburg Residenzplatz "Central Square" Set in the center of Altstadt, Residenzplatz is a must visit when visiting the city. Dating back to the 16th Century, it was built by the then Archbishop of Salzburg, Wolf Dietrich Raitenau. -

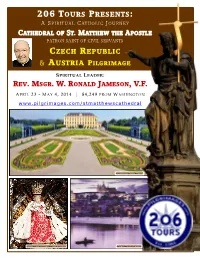

Rev. Msgr. W. Ronald Jameson, V.F

206 TOURS PRESENTS: A S PIRITUAL C ATHOLIC J OURNEY CATHEDRAL OF ST. MATTHEW THE APOSTLE PATRON SAINT OF CIVIL SERVANTS CZECH REPUBLIC & AUSTRIA PILGRIMAGE SPIRITUAL LEADER: REV. MSGR. W. RONALD JAMESON, V.F. A PRIL 23 - M AY 4, 2014 | $4,249 FROM W ASHINGTON www.pilgrimages.com/stmatthewscathedral Schonbrunn Palace, Vienna Infant Jesus of Prague, Czech Republic Prague, Czech Republic Strauss Statute in Stadt Park, Vienna St. Charles Church, Vienna ABOUT REV. MSGR. W. RONALD JAMESON, V.F. Msgr. Jameson was raised in Hughesville, MD and studied at St. Charles College High School, St. Mary’s Seminary in Baltimore and the Theological College of the Catholic University of America. Msgr. Jameson was eventually ordained in 1968. Following his ordination, he completed two assignments in Maryland parishes, followed by an assign- ment for St. Matthew's Cathedral (1974- 1985). Msgr. Jameson has served God in many ways. He has achieved many titles, assumed positions for a variety of archdiocesan posi- tions and served or serves on multiple na- tional boards. In October 2007, Theological College bestowed on Msgr. Jameson its Alumnus Lifetime Service Award honoring him as Pastor-Leader of the Faith Communi- ty due to his many archdiocesan positions and his outstanding service to God. His legacy to St. Matthew's Cathedral will undoubtedly be his enduring interest in building parish community, establishing a parish archive and history project, orches- trating the Cathedral's major restoration project and the construction of the adjoining rectory and office building project on Rhode Island Avenue (1998-2006). *NOTE: The "V.F." after Msgr Jameson's name denotes that he is appointed by the Archbishop as a Vicar Forane or Dean of one of the ecclesial subdivisions (i.e. -

Leopold and Wolfgang Mozart's View of the World

Between Aufklärung and Sturm und Drang: Leopold and Wolfgang Mozart’s View of the World by Thomas McPharlin Ford B. Arts (Hons.) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy European Studies – School of Humanities and Social Sciences University of Adelaide July 2010 i Between Aufklärung and Sturm und Drang: Leopold and Wolfgang Mozart’s View of the World. Preface vii Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Leopold Mozart, 1719–1756: The Making of an Enlightened Father 10 1.1: Leopold’s education. 11 1.2: Leopold’s model of education. 17 1.3: Leopold, Gellert, Gottsched and Günther. 24 1.4: Leopold and his Versuch. 32 Chapter 2: The Mozarts’ Taste: Leopold’s and Wolfgang’s aesthetic perception of their world. 39 2.1: Leopold’s and Wolfgang’s general aesthetic outlook. 40 2.2: Leopold and the aesthetics in his Versuch. 49 2.3: Leopold’s and Wolfgang’s musical aesthetics. 53 2.4: Leopold’s and Wolfgang’s opera aesthetics. 56 Chapter 3: Leopold and Wolfgang, 1756–1778: The education of a Wunderkind. 64 3.1: The Grand Tour. 65 3.2: Tour of Vienna. 82 3.3: Tour of Italy. 89 3.4: Leopold and Wolfgang on Wieland. 96 Chapter 4: Leopold and Wolfgang, 1778–1781: Sturm und Drang and the demise of the Mozarts’ relationship. 106 4.1: Wolfgang’s Paris journey without Leopold. 110 4.2: Maria Anna Mozart’s death. 122 4.3: Wolfgang’s relations with the Weber family. 129 4.4: Wolfgang’s break with Salzburg patronage. -

Salzb., the Last Day of Sept. Mon Trés Cher Fils!1 1777 This Morning There

0340. LEOPOLD MOZART TO HIS SON, MUNICH Salzb., the last day of Sept. Mon trés cher Fils!1 1777 This morning there was a rehearsal in the theatre, Haydn2 had to write the intermezzos between the acts for Zayre.3As early as 9 o’clock, they were coming in one after another, [5] after 10 o’clock it started, and it was not finished until towards half past 11. Of course, there was always Turkish music4 amongst it, then also a march. Countess von Schönborn5 also came to the rehearsal, driven in a chaise by Count Czernin.6 The music is said to fit the action very well and to be good. Now, although there was nothing but instrumental music, the court clavier had to be brought over, [10] for Haydn played. The previous day, Hafeneder’s music for the end of the university year was performed by night7 in the Noble Pages’ garden8 at the back, where Rosa9 lived. The Prince10 dined at Hellbrunn,11 and the play started after half past 6. Herr von Mayregg12 stood at the door as commissioner, and the 2 valets Bauernfeind and Aigner collected the tickets, the nobility had [15] no tickets, and yet 600 had been given out. We saw the throng from the window, but it was not as great as I had imagined, for almost half the tickets were not used. They say it is to be performed quite frequently, and then I can hear the music if I want. I saw the main stage rehearsal. The play was already finished at half past 8; consequently, the Prince [20] and everyone had to wait half an hour for their coaches. -

European Pilgrimage with Oberammergau Passion Play

14 DAYS BIRKDALE & MANLY PARISH European Pilgrimage with Oberammergau Passion Play 11 Nights / 14 Days Fri 24 July - Thu 6 Aug, 2020 • Bologna (2) • Ravenna • Padua (2) • Venice • Ljubljana (2) • Lake Bled • Salzburg (3) • Innsbruck • Oberammergau Passion Play (2) Accompanied by: Fr Frank Jones Church of the Assumption - Bled Island, Slovenia Triple Bridge, Slovenia St Anthony Basilica, Padua Italy Mondsee, Austria Meal Code DAY 5: TUESDAY 28 JULY – VENICE & PADUA (BD) DAY 8: FRIDAY 31 JULY – VIA LAKE BLED TO (B) = Breakfast (L) = Lunch (D) = Dinner Venice comprises a dense network of waterways SALZBURG (BD) with 117 islands and more than 400 bridges over Departing Ljubljana this morning we travel DAY 1: FRIDAY 24 JULY - DEPART FOR its 150 canals. Instead of main streets, you’ll find through rural Slovenia towards the Julian Alps EUROPE main canals, instead of cars, you’ll find Gondolas! to Bled. Upon arrival we take a short boat ride to Bled Island (weather permitting), where we DAY 2: SATURDAY 25 JULY - ARRIVE Today we travel out to Venice, known as visit the Church of the Assumption. BOLOGNA (D) Europe’s most romantic destination. As we Today we arrive into Bologna. This is one board our boat transfer we enjoy our first Returning to the mainland, we visit the of Italy’s most ancient cities and is home to glimpses of this unique city. Our time here medieval Bled Castle perched on a cliff high above the lake, offering splendid views of the its oldest university. The Dominicans were begins with Mass in St Mark’s Basilica, built surrounding Alpine peaks and lake below. -

Magnificent Journeys

Magnificent Journeys Taking Pilgrims to Holy Places TM Join us for our 20th Anniversary Pilgrimage SPRING 2020 VOL. 13 inRiver South France with excursions Cruise to Paris and Lourdes FLORENCE ROME MONTRÉAL JERUSALEM Founder’s Letter Dear Pilgrim Family, nother amazing year has Acome to an end. It is crazy to think that the second decade of the third millennium has come to completion. As I reflect on the many blessings of the past year, I am reminded of Luke 17:11-19. In this passage Jesus healed 10 lepers, and only one, the Samari- tan, comes back to thank Jesus. We should never be one of the nine who failed to ex- press gratitude. My husband, Ray, and I are so thankful for the many blessings and mir- acles with which God continues to grace our family, Magnificat Travel, and you, our pilgrimage family. A pilgrim who traveled to France with Immaculate Conception Church in Den- ham Springs, Louisiana, wrote to us saying, “Words cannot adequately express what this pilgrimage meant to my husband and me. We learned so much about the saints and realized what great examples of faith they are to us. The sites were beautiful and The Tregre Family gathers for the holidays (from top left): Andrew Tregre, Matthew Tregre, Evelyn the experience wonderful.” Tregre, Brandon Marin and Mike Templet. Front row: Alexis Tregre, Caroline Tregre, Ray Tregre, In 2019, we partnered with 44 Spiri- Amelia Tregre, Maria Tregre, Katie Templet and Charlotte Templet. tual Directors and Leaders as we coordi- nated and led 34 pilgrimages and missions around the world. -

OCTOBER, 2006 St. Mark's Pro-Cathedral Hastings, Nebraska

THE DIAPASON OCTOBER, 2006 St. Mark’s Pro-Cathedral Hastings, Nebraska Cover feature on pages 31–32 ica and Great Britain. The festival will Matthew Lewis; 10/22, Thomas Spacht; use two of the most significant instru- 10/29, Justin Hartz; November 5, Rut- THE DIAPASON ments in London for its Exhibition- gers Collegium Musicum; 11/12, Mark A Scranton Gillette Publication Concerts: the original 1883 “Father” Pacoe; 11/19, David Schelat; 11/26, Ninety-seventh Year: No. 10, Whole No. 1163 OCTOBER, 2006 Willis organ in St. Dominic’s Priory organ students of the Mason Gross Established in 1909 ISSN 0012-2378 (Haverstock Hill) and the newly School of the Arts, Rutgers; December restored 1963 Walker organ in St. John 10, Vox Fidelis; December 17, Advent An International Monthly Devoted to the Organ, the Evangelist (Islington). Lessons & Carols. For information: the Harpsichord, the Carillon and Church Music The first two Exhibition-Concerts in <christchurchnewbrunswick.org>. London take place on October 7 and 14, and both are preceded by pubic discus- St. James Episcopal Cathedral, sions on organ composition today. Addi- Chicago, Illinois, continues its music CONTENTS Editor & Publisher JEROME BUTERA [email protected] tionally, there are three ‘new music’ series: October 14, Mozart chamber 847/391-1045 concerts at Westminster Abbey, West- music; 10/15, The Cathedral Choir, FEATURES minster Cathedral and St. Dominic’s soloists, and chamber orchestra; Introducing Charles Quef Priory. Full details can be found on the November 5, Choral Evensong; 11/19, Forgotten master of La Trinité in Paris Associate Editor JOYCE ROBINSON festival website <www.afnom.org>. -

History of Schloss Leopoldskron

SALZBURG SEMINAR SCHLOSS LEOPOLDSKRON HISTORY OF SCHLOSS LEOPOLDSKRON Schloss Leopoldskron was commissioned as a family estate in 1736 by the Prince Archbishop of Salzburg, Leopold Anton Freiherr von Firmian (1679-1744), a member of a Tyrolean noble family whose lineage can be traced back to 1185. The Scottish Benedictine monk Bernhard Stuart is regarded as Leopoldskrons master builder. The stucco work on the ceilings done by Johann Kleber are described as “the best example of rococo stucco the land can offer”. Leopold Firmian was a great lover of science and the arts, but is most remembered for his role in the expulsion of more than 22,000 Protestants from the Archbishopric of Salzburg. Leopold’s harsh actions were noticed all over Europe and both Salzburg’s economy and the reputation of the Firmian family suffered severely as a result. The commission of Schloss Leopoldskron was, in part, an attempt by the Archbishop to rescue the social standing of his family. Schloss Leopoldskron and Lake, A special law made the property an inalienable Watercolor, pen and ink drawing, possession of the family. In May 1744, Leopold Late 19th Century. deeded the completed Schloss over to his nephew, Count Laktanz Firmian. After his death later in the same year, the Archbishop’s body was buried in Salzburg’s cathedral, but his heart remains below the Chapel of the Schloss, which, as is inscribed on the chapel floor, he “loved so dearly.” Count Laktanz, a collector of art and an artist himself, enriched Schloss Leopoldskron with the largest collection of paintings Salzburg had ever known, including works of artists such as Rembrandt, Rubens, Dürer, and Titian. -

Spring 2013 2012

LoremSpring Ipsum2013 Dolor Spring 2012 Volume 4 Celebrating the joy of singing The mission of Rogue Valley Chorale is to inspire and enrich our communities through the performance of great choral music performed by choruses of all ages. Rogue Valley Chorale Association Newsletter 40 Years of Memories Rogue Valley Chorale Celebrates Its Memories! Ah, memories! With a 40th Anniversary Season forty year history of making music the Rogue Valley Chorale has This season marks th built a treasury of memories. the 40 anniversary of the Our February 23 and 24 concerts Rogue Valley are entitled Hallelujah. They are Chorale. Since its programs of sacred music founding in 1973, through time, a tribute to how the chorale has religion has shaped our culture contributed to the and musical repertoire. We will cultural atmosphere of Southern Oregon by providing ! feature a small portion of the audiences with exceptional classical and works we have sung over the years. Some selections have contemporary choral works. We intend for our 40th been pieces requested by our loyal patrons. Chorale anniversary performances to be memorable. Many of members who were especially moved while singing them in the musical selections performed during our the past suggested others. Some of the numbers to be remaining concerts of the season will be old favorites, presented were chosen because of the memorable places special works, as well as commissioned pieces. in which they were performed. The Chorale has sung many Masses over the years from February 23 at Bethel Church and February 24, Palestrina to excerpts from Bernstein’s Mass written for the 2013 at the Craterian …Hallelujah… a program dedication of the Washington D.C. -

Music of HAYDN, MOZART & C.P.E. BACH

harvard university choir harvard baroque chamber orchestra Music of HAYDN, MOZART &Joseph C.P.E. Haydn • L’infedeltà BACH Delusa (Sinfonia) W. A. Mozart • Vesperae solennes de Confessore C. P. E. Bach • Magnificat sunday, november 3, 2019 • 4 pm MUSIC OF HAYDN, MOZARTh & C.P.E. BACH L’infedeltà Delusa (Sinfonia), Hob. XXVIII:5 (1773) Josef Haydn (1732–1809) h Vesperae solennes de Confessore, K. 339 (1780) Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791) 1. Dixit Dominus (Psalm 110) (Rena Cohen, Elizabeth Corbus, Patrick Braga, Christian Carson, soloists) 2. Confitebor tibi Domine (Psalm 111) (Benjamin Wenzelberg, Claire Murphy, Samuel Rosner, Henrique Neves) 3. Beatus vir qui timet Dominum (Psalm 112) (Sophie Choate, Camille Sammeth, Adam Mombru, Freddie MacBruce) 4. Laudate pueri Dominum (Psalm 113) 5. Laudate Dominum omnes gentes (Psalm 117) (Isabella Kopits) 6. Magnificat (Angela Eichhorst, Cana McGhee, Jasper Schoff, Joseph Gauvreau) h Intermissionh (10 minutes) Magnificat, Wq 215, H. 772 (1749, rev. 1779) Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach (1714–1788) 1. Magnificat 2. Quia respexit (Katharine Courtemanche) 3. Quia fecit 4. Et misericordia (Samuel Rosner) 5. Fecit potentiam (Henrique Neves) 6. Deposuit potentes de sede (Katherine Lazar and Gregory Lipson) 7. Suscepit Israel (May Wang) 8. Gloria patri 9. Sicut erat in principio h Harvard University Choir Harvard Baroque Chamber Orchestra Edward Elwyn Jones, conductor 1 ELCOME to the Memorial Church of Harvard University, and to this afternoon’s fall concert, a collaboration between the Harvard University Choir and the Harvard Baroque Chamber Or- Wchestra. It has been a thrill to prepare this program with such an enthusiastic group of young singers and instrumentalists. -

Cathedral of St. Matthew the Apostle Vienna, Salzburg & Prague

A Marian Pilgrimage Throughout the Majestic Alps Region Cathedral of St. Matthew the Apostle Rev. Msgr. W. Ronald Jameson, V.F., Rector Vienna, Salzburg & Prague A PRIL 23 - M AY 4, 2014 $4,249 FROM W ASHINGTON St. Charles Church, Vienna Infant Jesus of Prague, Czech Republic Prague, Czech Republic www.pilgrimages.com/stmatthewscathedral A Special Invitation to the Friends and Families of The Cathedral of St Matthew the Apostle Dear Friends, It is with great joy that The Cathedral of St. Matthew the Apostle will be embarking on a 12-day pilgrimage to Vienna, Salzburg and Prague, April 23 - May 4, 2014. We would like to personally invite you, your relatives and your friends, to join us on this special trip, which promises to be an exciting, enjoyable and spiritually uplifting experience for all. A visit to the Alpine Region of Europe has a wonderful mix of history, breathtaking views, Marian shrines, and musical venues. I hope you will join me in strengthening our relationship with Mary in prayer and fellowship by visiting so many blessed churches in this region. Join us for what promises to be a memorable experience to cherish. We look forward to having you with us! Sincerely, Reverend Msgr. W. Ronald Jameson, VF, Rector Originally from Hughesville, Maryland, Msgr. Jameson attended St. Mary’s Seminary in Baltimore and the Theological College of the Catholic University of America and was ordained to the priesthood in 1968. Following his ordination, he completed two assignments in Maryland parishes, followed by his first assignment at St. Matthew’s Cathe- dral. -

The Marian Philatelist, Whole No. 50

University of Dayton eCommons The Marian Philatelist Marian Library Special Collections 9-1-1970 The Marian Philatelist, Whole No. 50 A. S. Horn W. J. Hoffman Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/imri_marian_philatelist Recommended Citation Horn, A. S. and Hoffman, W. J., "The Marian Philatelist, Whole No. 50" (1970). The Marian Philatelist. 50. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/imri_marian_philatelist/50 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Marian Library Special Collections at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Marian Philatelist by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Marian Philatelist PUBLISHED BY THE MARIAN PHILATELIC STUDY GROUP Business Address: Rev. A. S. Horn Chairman 424 W. Crystal View Avenue W. J. Hoffman Editor Orange, California 92665 Vol. 8 No. 5 Whole No. 50 SEPTEMBER 1, 1970 NEW I S S U E S The first day cancel also depicts the Abb ey; see France 94 on page 49. BRAZIL: (Class 1). A 20 cts stamp issued May 10, 1970 for Mother's Day. Design de HUNGARY: (Class 8). A 3-stamp picts a painting by an anonymous artist; semi-postal issue, all having original now in the St. Antonio Monastery, a 2+1 ft value, issued March 7, Rio de Janeiro. 1970 to publicize the 1971 Bu dapest Stamp Exhibition comm emorating the centenary of the Hungarian postage stamp. The golden brown and multicolored stamp (Scott B276) includes the CHURCH OF OUR LADY, also known as "The Coronation Church" and the "Mathias Church." The church is at top left.