Music of HAYDN, MOZART & C.P.E. BACH

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vol. XII/6, Vienna 1999)

Bruckner Journal Issued three times a year and sold by subscription Editorial and advertising: telephone 0115 928 8300 2 Rivergreen Close, Beeston, GB-Nottingham NG9 3ES Subscriptions and mailing: telephone 01384 566 383 4 Lu)worth Close, Halesowen, West Midlands B63 2UJ VOLUME FIVE, NUMBER THREE, NOVEMBER 2001 Editor: Peter Palmer Managing Editor: Raymond Cox Associate Editor: Crawford Howie In This Issue page Concerts 2 Compact Discs 7 Publications 14 Skrowaczewski Speaks 17 Bruckner1s Third: 1st Edition by Crawford Howie 22 Austerity or Charm ,. by David Aldeborgh 26 l: Poem by Adam Zagajewski 32 Feedback 33 Jottings 34 Calendar 36 Copyright in all material is retained by the author. Photograph (page 9) by Peter Kloos. Translation (pages 17-21) by Peter Palmer. Silhouette: Otto Bohler. Contributors - the next copy deadline is 15 January 2002. Material other than letters in typescript, please. BUS T BY VI KTOR TIL GN E R - see page 16 2 CON C E R T S On Sunday 3 June lorin Maazel conducted the Phil harmonia Orchestra in Bruckner's Eighth Symphony in the Royal Festival Hall, london. The division of critical opinion in the national broadsheets is largely reflected in the reactions of our own correspondents. First, JEREMY WILKINSON reports on a performance given by the same forces two nights earlier in the De Montfort Hall, Leicester. For him, this was a deeply personal occasion: We were celebrating my mother's birthday but also commemorating the anniversary of the loss of my twin brother. How fitting to come and hear Bruckner's great masterpiece, so full of bleakness, tension and emotion. -

Messe E-Moll WAB 27 Zweite Fassung/Second Version 1882

Anton BRUCKNER Messe e-Moll WAB 27 Zweite Fassung/Second version 1882 Coro (SSAATTBB) 2 Oboi, 2 Clarinetti, 2 Fagotti, 4 Corni, 2 Trombe, 3 Tromboni herausgegeben von/edited by Dagmar Glüxam Urtext Partitur/Full score C Carus 27.093 Inhalt / Contents Vorwort 4 Foreword 8 Abbildungen 12 Kyrie (Coro SSAATTBB) 14 Gloria (Coro) 20 Credo (Coro) 32 Sanctus (Coro) 49 Benedictus (Coro SSATTBB) 55 Agnus Dei (Coro SSAATTBB) 63 Kritischer Bericht 73 Zu diesem Werk liegt folgendes Aufführungsmaterial vor: Partitur (Carus 27.093), Klavierauszug (Carus 27.093/03), Klavierauszug XL Großdruck (Carus 27.093/04), Chorpartitur (Carus 27.093/05), komplettes Orchestermaterial (Carus 27.093/19). The following performance material is available: full score (Carus 27.093), vocal score (Carus 27.093/03), vocal score XL in larger print (Carus 27.093/04), choral score (Carus 27.093/05), complete orchestral material (Carus 27.093/19). Carus 27.093 3 Vorwort Als Anton Bruckner (1824–1896) zwischen August und November C-Dur (WAB 31) für vierstimmigen gemischten Chor a cappella 1866 seine Messe in e-Moll (WAB 27) komponierte, konnte er (1. Fassung 1835–1843, 2. Fassung 1891) oder der Windhaager bereits eine langjährige Erfahrung als Kirchenmusiker aufweisen und Messe in C-Dur für Alt, zwei Hörner und Orgel (WAB 25; 1842) auch auf ein überaus umfangreiches kirchenmusikalisches Œuvre können hier etwa die Messe ohne Gloria in d-Moll („Kronstorfer zurückblicken.1 Schon als Kind wurde er durch seinen musikbe- Messe“; WAB 146, 1844) für vierstimmigen gemischten Chor a geisterten Vater und Schullehrer Anton Bruckner (1791–1837) zur cappella oder das Requiem für vierstimmigen Männerchor und Mitwirkung – u. -

Best Local Scene in Salzburg"

"Best Local Scene in Salzburg" Gecreëerd door : Cityseeker 4 Locaties in uw favorieten Old Town (Altstadt) "Old Town Salzburg" The historic nerve center of Salzburg, the Altstadt is an enchanting district that spans 236 hectares (583.16 acres). The locale's narrow cobblestone streets conceal an entire constellation of breathtaking heritage sites and architectural marvels that showcase Salsburg's vibrant past. Some of the area's prime attractions include the Salzburg Cathedral, Collegiate by Public Domain Church, Franciscan Church, Holy Trinity Church, Nonnberg Abbey, and Mozart's birthplace. +43 662 88 9870 (Tourist Information) Getreidegasse, Salzburg Getreidegasse "Salzburg's Most Famous Shopping Street" Salzburg's Getreidegasse is the most famous street in the city, therefore the most crowded. If you are really interested in getting a view of the charming old houses, try to visit early, preferably before 10 in the morning - pretty portals and wonderful courtyards can only be seen and appreciated then. The Getreidegasse is famous for its wrought-iron signs, by Edwin Lee dating from the 16th to the 19th centuries - the design of the signs dates back to the Middle Ages! It is worth taking a second look at the houses because they are adorned with dates, symbols or the names of their owners, so they often tell their own history. +43 662 8 8987 [email protected] Getreidegasse, Salzburg Residenzplatz "Central Square" Set in the center of Altstadt, Residenzplatz is a must visit when visiting the city. Dating back to the 16th Century, it was built by the then Archbishop of Salzburg, Wolf Dietrich Raitenau. -

75Thary 1935 - 2010

ANNIVERS75thARY 1935 - 2010 The Music & the Artists of the Bach Festival Society The Mission of the Bach Festival Society of Winter Park, Inc. is to enrich the Central Florida community through presentation of exceptionally high-quality performances of the finest classical music in the repertoire, with special emphasis on oratorio and large choral works, world-class visiting artists, and the sacred and secular music of Johann Sebastian Bach and his contemporaries in the High Baroque and Early Classical periods. This Mission shall be achieved through presentation of: • the Annual Bach Festival, • the Visiting Artists Series, and • the Choral Masterworks Series. In addition, the Bach Festival Society of Winter Park, Inc. shall present a variety of educational and community outreach programs to encourage youth participation in music at all levels, to provide access to constituencies with special needs, and to participate with the community in celebrations or memorials at times of significant special occasions. Adopted by a Resolution of the Bach Festival Society Board of Trustees The Bach Festival Society of Winter Park, Inc. is a private non-profit foundation as defined under Section 509(a)(2) of the Internal Revenue Code and is exempt from federal income taxes under IRC Section 501(c)(3). Gifts and contributions are deductible for federal income tax purposes as provided by law. A copy of the Bach Festival Society official registration (CH 1655) and financial information may be obtained from the Florida Division of Consumer Services by calling toll-free 1-800-435-7352 within the State. Registration does not imply endorsement, approval, or recommendation by the State. -

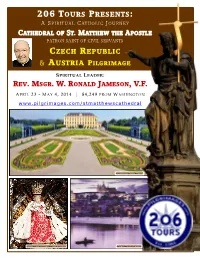

Rev. Msgr. W. Ronald Jameson, V.F

206 TOURS PRESENTS: A S PIRITUAL C ATHOLIC J OURNEY CATHEDRAL OF ST. MATTHEW THE APOSTLE PATRON SAINT OF CIVIL SERVANTS CZECH REPUBLIC & AUSTRIA PILGRIMAGE SPIRITUAL LEADER: REV. MSGR. W. RONALD JAMESON, V.F. A PRIL 23 - M AY 4, 2014 | $4,249 FROM W ASHINGTON www.pilgrimages.com/stmatthewscathedral Schonbrunn Palace, Vienna Infant Jesus of Prague, Czech Republic Prague, Czech Republic Strauss Statute in Stadt Park, Vienna St. Charles Church, Vienna ABOUT REV. MSGR. W. RONALD JAMESON, V.F. Msgr. Jameson was raised in Hughesville, MD and studied at St. Charles College High School, St. Mary’s Seminary in Baltimore and the Theological College of the Catholic University of America. Msgr. Jameson was eventually ordained in 1968. Following his ordination, he completed two assignments in Maryland parishes, followed by an assign- ment for St. Matthew's Cathedral (1974- 1985). Msgr. Jameson has served God in many ways. He has achieved many titles, assumed positions for a variety of archdiocesan posi- tions and served or serves on multiple na- tional boards. In October 2007, Theological College bestowed on Msgr. Jameson its Alumnus Lifetime Service Award honoring him as Pastor-Leader of the Faith Communi- ty due to his many archdiocesan positions and his outstanding service to God. His legacy to St. Matthew's Cathedral will undoubtedly be his enduring interest in building parish community, establishing a parish archive and history project, orches- trating the Cathedral's major restoration project and the construction of the adjoining rectory and office building project on Rhode Island Avenue (1998-2006). *NOTE: The "V.F." after Msgr Jameson's name denotes that he is appointed by the Archbishop as a Vicar Forane or Dean of one of the ecclesial subdivisions (i.e. -

Mendelssohn's Elijah

Boston University College of Fine Arts School of Music presents Boston University Symphony Orchestra and Symphonic Chorus Mendelssohn’s Elijah Ann Howard Jones conductor Monday, April 11 Symphony Hall Founded in 1872, the School of Music combines the intimacy and intensity of conservatory training with a broadly based, traditional liberal arts education at the undergraduate level and intense coursework at the graduate level. The school offers degrees in performance, composition and theory, musicology, music education, collaborative piano, historical performance, as well as a certificate program in its Opera Institute, and artist and performance diplomas. Founded in 1839, Boston University is an internationally recognized private research university with more than 32,000 students participating in undergraduate, graduate, and professional programs. BU consists of 17 colleges and schools along with a number of multidisciplinary centers and institutes which are central to the school’s research and teaching mission. The Boston University College of Fine Arts was created in 1954 to bring together the School of Music, the School of Theatre, and the School of Visual Arts. The University’s vision was to create a community of artists in a conservatory-style school offering professional training in the arts to both undergraduate and graduate students, complemented by a liberal arts curriculum for undergraduate students. Since those early days, education at the College of Fine Arts has begun on the BU campus and extended into the city of Boston, a rich center of cultural, artistic and intellectual activity. Boston University College of Fine Arts School of Music Boston University Symphonic Chorus April 11, 2011 Boston University Symphony Orchestra Symphony Hall Ann Howard Jones, conductor The 229th concert in the 2010–11 season Elijah, op. -

22. BIS 25. MAI 2015 Die Sparkasse Regensburg Treibt Kultur An

€ Preis: 5,00 MUSIK VOM MITTELALTER BIS ZUR ROMANTIK KONZERTE AN HISTORISCHEN STÄTTEN Regensburger Domspatzen L’ Orfeo Barockorchester (Österreich) Profeti della Quinta (Israel/Schweiz) Rachel Podger (Großbritannien) Echo du Danube (Deutschland) Ensemble Leones (Deutschland/Schweiz) Musica Humana 430 (Polen/Deutschland) The Marian Consort (Großbritannien) Rose Consort of Viols (Großbritannien) Ensemble Stravaganza (Frankreich) Concerto Palatino (Italien) Batzdorfer Hofkapelle (Deutschland) Harmonie Universelle (Deutschland) Phantasm (Großbritannien) New York Polyphony (USA) Il Suonar Parlante Orchestra (Italien) Les Ambassadeurs (Frankreich) Verkaufsausstellung von Nachbauten historischer Musikinstrumente, von Noten, Büchern und CDs 22. BIS 25. MAI 2015 Die Sparkasse Regensburg treibt Kultur an. Mit rund 640.000 Euro engagiert sich die Sparkasse Regensburg ganz weit vorne als Förderin der Kunst und Kultur in Regensburg. Viele große Musik-Ereignisse – darunter Jugend musiziert, die Tage Alter Musik, das Musikfestival Palazzo und die Schloss- festspiele Thurn und Taxis – wären ohne die Unterstützung der Sparkasse Regens- burg nicht möglich. s Sparkasse Regensburg TAGE ALTER Musik REGEnsbuRG MAi 2015 VVoorrwwoorrtt GGrruußßwwoorrtt GGrruußßwwoorrtt Vier Tage Alte Musik pur Musikereignis von internationalem Rang Einzigartiges Festival Liebe Musikfreunde, die TAGE ALTER MUSIK REGENS - BURG finden in diesem Jahr zum 31. Mal statt. In den vier Tagen des Festi- vals können wir Ihnen auch heuer wieder anregende Begegnungen mit Musik vergangener -

Leopold and Wolfgang Mozart's View of the World

Between Aufklärung and Sturm und Drang: Leopold and Wolfgang Mozart’s View of the World by Thomas McPharlin Ford B. Arts (Hons.) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy European Studies – School of Humanities and Social Sciences University of Adelaide July 2010 i Between Aufklärung and Sturm und Drang: Leopold and Wolfgang Mozart’s View of the World. Preface vii Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Leopold Mozart, 1719–1756: The Making of an Enlightened Father 10 1.1: Leopold’s education. 11 1.2: Leopold’s model of education. 17 1.3: Leopold, Gellert, Gottsched and Günther. 24 1.4: Leopold and his Versuch. 32 Chapter 2: The Mozarts’ Taste: Leopold’s and Wolfgang’s aesthetic perception of their world. 39 2.1: Leopold’s and Wolfgang’s general aesthetic outlook. 40 2.2: Leopold and the aesthetics in his Versuch. 49 2.3: Leopold’s and Wolfgang’s musical aesthetics. 53 2.4: Leopold’s and Wolfgang’s opera aesthetics. 56 Chapter 3: Leopold and Wolfgang, 1756–1778: The education of a Wunderkind. 64 3.1: The Grand Tour. 65 3.2: Tour of Vienna. 82 3.3: Tour of Italy. 89 3.4: Leopold and Wolfgang on Wieland. 96 Chapter 4: Leopold and Wolfgang, 1778–1781: Sturm und Drang and the demise of the Mozarts’ relationship. 106 4.1: Wolfgang’s Paris journey without Leopold. 110 4.2: Maria Anna Mozart’s death. 122 4.3: Wolfgang’s relations with the Weber family. 129 4.4: Wolfgang’s break with Salzburg patronage. -

Salzb., the Last Day of Sept. Mon Trés Cher Fils!1 1777 This Morning There

0340. LEOPOLD MOZART TO HIS SON, MUNICH Salzb., the last day of Sept. Mon trés cher Fils!1 1777 This morning there was a rehearsal in the theatre, Haydn2 had to write the intermezzos between the acts for Zayre.3As early as 9 o’clock, they were coming in one after another, [5] after 10 o’clock it started, and it was not finished until towards half past 11. Of course, there was always Turkish music4 amongst it, then also a march. Countess von Schönborn5 also came to the rehearsal, driven in a chaise by Count Czernin.6 The music is said to fit the action very well and to be good. Now, although there was nothing but instrumental music, the court clavier had to be brought over, [10] for Haydn played. The previous day, Hafeneder’s music for the end of the university year was performed by night7 in the Noble Pages’ garden8 at the back, where Rosa9 lived. The Prince10 dined at Hellbrunn,11 and the play started after half past 6. Herr von Mayregg12 stood at the door as commissioner, and the 2 valets Bauernfeind and Aigner collected the tickets, the nobility had [15] no tickets, and yet 600 had been given out. We saw the throng from the window, but it was not as great as I had imagined, for almost half the tickets were not used. They say it is to be performed quite frequently, and then I can hear the music if I want. I saw the main stage rehearsal. The play was already finished at half past 8; consequently, the Prince [20] and everyone had to wait half an hour for their coaches. -

European Pilgrimage with Oberammergau Passion Play

14 DAYS BIRKDALE & MANLY PARISH European Pilgrimage with Oberammergau Passion Play 11 Nights / 14 Days Fri 24 July - Thu 6 Aug, 2020 • Bologna (2) • Ravenna • Padua (2) • Venice • Ljubljana (2) • Lake Bled • Salzburg (3) • Innsbruck • Oberammergau Passion Play (2) Accompanied by: Fr Frank Jones Church of the Assumption - Bled Island, Slovenia Triple Bridge, Slovenia St Anthony Basilica, Padua Italy Mondsee, Austria Meal Code DAY 5: TUESDAY 28 JULY – VENICE & PADUA (BD) DAY 8: FRIDAY 31 JULY – VIA LAKE BLED TO (B) = Breakfast (L) = Lunch (D) = Dinner Venice comprises a dense network of waterways SALZBURG (BD) with 117 islands and more than 400 bridges over Departing Ljubljana this morning we travel DAY 1: FRIDAY 24 JULY - DEPART FOR its 150 canals. Instead of main streets, you’ll find through rural Slovenia towards the Julian Alps EUROPE main canals, instead of cars, you’ll find Gondolas! to Bled. Upon arrival we take a short boat ride to Bled Island (weather permitting), where we DAY 2: SATURDAY 25 JULY - ARRIVE Today we travel out to Venice, known as visit the Church of the Assumption. BOLOGNA (D) Europe’s most romantic destination. As we Today we arrive into Bologna. This is one board our boat transfer we enjoy our first Returning to the mainland, we visit the of Italy’s most ancient cities and is home to glimpses of this unique city. Our time here medieval Bled Castle perched on a cliff high above the lake, offering splendid views of the its oldest university. The Dominicans were begins with Mass in St Mark’s Basilica, built surrounding Alpine peaks and lake below. -

Magnificent Journeys

Magnificent Journeys Taking Pilgrims to Holy Places TM Join us for our 20th Anniversary Pilgrimage SPRING 2020 VOL. 13 inRiver South France with excursions Cruise to Paris and Lourdes FLORENCE ROME MONTRÉAL JERUSALEM Founder’s Letter Dear Pilgrim Family, nother amazing year has Acome to an end. It is crazy to think that the second decade of the third millennium has come to completion. As I reflect on the many blessings of the past year, I am reminded of Luke 17:11-19. In this passage Jesus healed 10 lepers, and only one, the Samari- tan, comes back to thank Jesus. We should never be one of the nine who failed to ex- press gratitude. My husband, Ray, and I are so thankful for the many blessings and mir- acles with which God continues to grace our family, Magnificat Travel, and you, our pilgrimage family. A pilgrim who traveled to France with Immaculate Conception Church in Den- ham Springs, Louisiana, wrote to us saying, “Words cannot adequately express what this pilgrimage meant to my husband and me. We learned so much about the saints and realized what great examples of faith they are to us. The sites were beautiful and The Tregre Family gathers for the holidays (from top left): Andrew Tregre, Matthew Tregre, Evelyn the experience wonderful.” Tregre, Brandon Marin and Mike Templet. Front row: Alexis Tregre, Caroline Tregre, Ray Tregre, In 2019, we partnered with 44 Spiri- Amelia Tregre, Maria Tregre, Katie Templet and Charlotte Templet. tual Directors and Leaders as we coordi- nated and led 34 pilgrimages and missions around the world. -

400Th ANNIVERSARY CONCERT CLAUDIO MONTEVERDI

CCM Chamber Choir Earl Rivers, conductor Sean Taylor, assistant conductor Sujin Kim, accompanist Soprano I Alto II Bass I CHORAL and Kerrie Caldwell Leah deGruyl Frederick Ballentine Holly Cameron Eric Jurenas Chance Eakin ORCHESTRA Emily McHugh Jill Phillips John McCarthy Marie McManama Stephanie Schoenhofer Edward Nelson SERIES PRESENTS Autumn West Katherine Wakefield Hern Ho Park Amanda Woodbury Tenor I Bass II Soprano II Michael Alcorn Charles Owens Olga Artemova Allan Chan Mark Diamond Samina Aslam Michael Jones Kevin DeVries Alexandra Kassouf Ian McEuen Gino Pinzone Fotina Naumenko Shawn Mlynek Thomas Richards Lauren Pollock Dashiell Waterbury Sean Taylor 400th ANNIVERSARY CONCERT Kathryn Papa Tenor II Alto I William Ayers CLAUDIO MONTEVERDI: Cameron Bowers Brandon Dean Glenda Crawford Ben Hansen Esther Kang Andrew Lovato VESPERO DELLA BEATA VIRGINE (1610) Katherine Krueger Gonçalo Lourenço Jesslyn Thomas Ian Ramirez CCM Philharmonia Chamber Orchestra CCM CHAMBER CHOIR Mark Gibson, music director CCM PHILHARMONIA CHAMBER Violin I Viola II Flute Scott Jackson Natasha Simmons Hanbyul Park ORCHESTRA Dan Wang Erin Rafferty Jihyun Park Hyejin Lee Megan Scharff Xiao Feng Cornetto GUEST EARLY MUSIC ARTISTS Kara Nam Cello Kiri Tollaksen* Sook Young Kim Christoph Sassmanshaus Shawn Spicer* Earl Rivers, conductor Sun Haeng Lee Violin II Chiao-Hsuan Kang Bassoon Gi Yeon Koh Eric Louie Abby Oliver Double Bass Thomas Reynolds Sunday, November 21, 2010 Jae Eun Lee Andrew Williams Christ Church Cathedral Sophie Borchmeyer Changin Son Trombone Yein Jin Michael Charbel Fourth and Sycamore Streets Ji Young Lee Kelly Jones Cincinnati, Ohio Ben Lightner 5:00 p.m. Viola I Benjamin Clymer Melissa Tschamler Claire Whitcomb Christopher Lape Sponsored by the CCM Tangeman Sacred Music Center *Guest Artist CCM has become an All-Steinway School through the kindness of its donors.