Transgender Issues About Lawnow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Universalization of LGBTQ Rights

ODUMUNC 2017 Issue Brief Third Committee: Social, Humanitarian, and Cultural Universalization of LGBTQ Rights by Tiana Bailey Old Dominion University Model United Nations Society are working to extend those rights to protect Introduction individual gender identity globally. But reverse processes also can be seen. Other UN Member The question of whether and how to States have established laws to bloc such acknowledge and protect individual rights over reforms, including prohibiting public discussion gender identity is a difficult issue for the of homosexuality and trans-gender rights and international community. Although UN Member criminalizing same-sex relationships. States have dealt with this and related policy issues for hundreds of years, traditionally state policy meant persecution. Since the mid- Twentieth Century, partially in response to the persecution and killing of Fascist and Nazi governments in the 1930s and ‘40s, policy has shifted to include greater protection of their rights as equal citizens. A major issue for the international community today is whether and how to best assure those rights, whether outright universalization of LGBTQ rights is feasible, and how to achieve it. Not only are more UN Member States seeking to universalize their rights, they seek to apply them to a growing group of people. This is seen in the rising importance of the abbreviation LGBTQ, originated in the 1990s to replace what was formerly known as ‘the gay community’, and include more diverse groups. LGBTQ stands for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (and/or questioning) individuals/identities. What At the worst, discrimination and persecution all share are non-heterosexual perspectives and leads to violent attacks. -

50 Note Character Selection Announcement

£50 note character selection announcement Speech given by Mark Carney Governor of the Bank of England Science and Industry Museum, Manchester 15 July 2019 I am grateful to Clare Macallan for her assistance in preparing these remarks, and to Matthew Corder, Toby Davies, Sarah John, Elizabeth Levett, Debbie Marriott and James Oxley for their help with background research and analysis. 1 All speeches are available online at www.bankofengland.co.uk/news/speeches It’s a pleasure to be at the Science and Industry Museum in Manchester. These galleries testify to the UK’s rich history of discovery in science, technology and industry. A little more than eight months ago, the Bank sought to recognise the UK’s extraordinary scientific heritage by asking people across the country to “Think Science” in order to help us choose the character to feature on the new £50 note. We were overwhelmed by the response. In six weeks, almost a quarter of a million nominations were submitted, from which we distilled a very long list of nearly 1,000 unique characters.1 The hard work of narrowing down these names to a shortlist of twelve options required the incomparable knowledge and tireless work of the Banknote Character Advisory Committee.2 On behalf of the Bank, I would like to thank the external members of the Advisory Committee – Dr Maggie Aderin-Pocock, Dr Emily Grossman, Professor Simon Schaffer, Dr Simon Singh, Professor Sir David Cannadine, Sandy Nairne and Baroness Lola Young – for their invaluable expert advice and unbridled enthusiasm. The characters that made it through to the final shortlist were: Mary Anning Charles Babbage and Ada Lovelace Paul Dirac Rosalind Franklin Stephen Hawking Caroline Herschel and William Herschel Dorothy Hodgkin James Clerk Maxwell Srinivasa Ramanujan Ernest Rutherford Frederick Sanger Alan Turing The shortlist epitomises the breadth and depth of scientific achievement in the UK. -

Simply Turing

Simply Turing Simply Turing MICHAEL OLINICK SIMPLY CHARLY NEW YORK Copyright © 2020 by Michael Olinick Cover Illustration by José Ramos Cover Design by Scarlett Rugers All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, write to the publisher at the address below. [email protected] ISBN: 978-1-943657-37-7 Brought to you by http://simplycharly.com Contents Praise for Simply Turing vii Other Great Lives x Series Editor's Foreword xi Preface xii Acknowledgements xv 1. Roots and Childhood 1 2. Sherborne and Christopher Morcom 7 3. Cambridge Days 15 4. Birth of the Computer 25 5. Princeton 38 6. Cryptology From Caesar to Turing 44 7. The Enigma Machine 68 8. War Years 85 9. London and the ACE 104 10. Manchester 119 11. Artificial Intelligence 123 12. Mathematical Biology 136 13. Regina vs Turing 146 14. Breaking The Enigma of Death 162 15. Turing’s Legacy 174 Sources 181 Suggested Reading 182 About the Author 185 A Word from the Publisher 186 Praise for Simply Turing “Simply Turing explores the nooks and crannies of Alan Turing’s multifarious life and interests, illuminating with skill and grace the complexities of Turing’s personality and the long-reaching implications of his work.” —Charles Petzold, author of The Annotated Turing: A Guided Tour through Alan Turing’s Historic Paper on Computability and the Turing Machine “Michael Olinick has written a remarkably fresh, detailed study of Turing’s achievements and personal issues. -

Speech by Sarah John at the Royal Institution, London, on Tuesday 16

Science and banknotes Remarks given by Sarah John, Chief Cashier The Royal Institution 16 July 2019 I would like to thank Elizabeth Levett, Gareth Pearce and Emma Sinclair for their help in preparing the text. 1 All speeches are available online at www.bankofengland.co.uk/news/speeches I’m delighted to be here this evening to explore the links between science and banknotes, a topic which seems even more appropriate the day after we announced the great scientist Alan Turing will be celebrated on the new £50 note. I am also pleased to be here in a personal capacity. As Chief Cashier with responsibility for our banknotes it is a peculiar honour to be able to speak in a room that has featured on one of those notes – as this very lecture theatre did on the £20 note, which depicted Michael Faraday, who himself often lectured here. Though thanks to a quirk in that note's design I can say for sure I am not the first Bank of England staff member to be pictured here; a section of the audience in the Faraday note are minute portraits of the then banknote design team, one of whom is still working at the Bank. As far as I'm aware he has yet to find a way to include himself in any of our other banknote designs – including the design we unveiled yesterday for the next £50 note featuring Alan Turing. As the central bank of the United Kingdom we have a wide range of responsibilities such as setting interest rates, regulating banks, setting rules for the financial system and storing gold. -

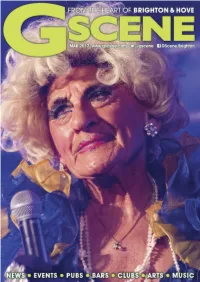

Gscene out & About

MAR 2017 CONTENTS GSCENE magazine ) www.gscene.com SUBLINE t @gscene f GScene.Brighton PUBLISHER Peter Storrow TEL 01273 749 947 EDITORIAL [email protected] ADS+ARTWORK [email protected] EDITORIAL TEAM James Ledward, Graham Robson, Sarah Green, Gary Hart, Alice Blezard SPORTS EDITOR Paul Gustafson ARTS EDITOR Michael Hootman SUB EDITOR Graham Robson DESIGN Michèle Allardyce FRONT COVER MODEL Maisie Trollette/David Raven PHOTOGRAPHER Hugo Michiels JOHN HAMILTON'S 50TH BIRTHDAY PARTY CONTRIBUTORS Simon Adams, Jaq Bayles, Jo Bourne, Nick Boston, Suchi Chatterjee, NEWS Craig Hanlon-Smith, Samuel Hall, Enzo Marra, Carl Oprey, Eric Page, 6 News Del Sharp, Gay Socrates, Syd Spencer, Brian Stacey, Michael Steinhage, Sugar Swan, Glen Stevens, Duncan SCENE LISTINGS Stewart, Craig Storrie, Mike Wall, Netty Wendt, Roger Wheeler 30 Gscene Out & About 32 Brighton & Hove PHOTOGRAPHERS Alice Blezard, Jack Lynn, 46 Solent James Ledward, Graham Hobson @captaincockroachphotographer Hugo Michiels, Stella Pix ARTS 48 Arts News DOCTOR BRIGHTONS 49 Art Matters 50 Classical Notes 51 All That Jazz © GSCENE 2017 REGULARS All work appearing in Gscene Ltd is copyright. It is to be assumed that the 29 Dance Music copyright for material rests with the magazine unless otherwise stated on the 29 DJ Profile: Oli Leslie page concerned. 47 Shopping No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in an electronic or other retrieval system, transmitted in any 52 Geek Scene form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or 53 Craig’s Thoughts otherwise without the prior knowledge and consent of the publishers. 54 Charlie Says The appearance of any person or any organisation in Gscene is not to be 55 Hydes’ Hopes construed as an implication of the sexual MARINE TAVERN orientation or political persuasion of such 55 Duncan’s Domain persons or organisations. -

LGBTQ+ Edition #Beattheboredom WELCOME to Your Personal MSV “Beat the Boredom” Activity Pack

ActivityPACK LGBTQ+ edition #BeatTheBoredom WELCOME to your personal MSV “Beat the Boredom” Activity Pack We, at MSV, want you to stay active physically and mentally and enjoy a variety of activities that you can do on your own This special edition activity pack celebrates LGBTQ+ month. Don’t worry, we have also included your favourites... word searches, crosswords, trivia and colouring. Please speak to your scheme manager if you need access to coloured pens etc. If you have any suggestions for future activities, we want to hear from you ENJOY and STAY SAFE CELEBRATING LGBTQ+ MONTH... LGBTQ+ History Month focuses on the celebration and recognition of LGBTQ+ people and culture; past and present to give educators scope to talk about the bigger picture of LGBTQ+ experience, in which LGBTQ+ people were the agents of change rather than just victims of prejudice... The Equality Act 2010 introduces a single equality duty on public bodies such as schools. It takes all previous equalities legislation and combines them into one overarching act. The Equality Act specifically protects the rights of people who hold characteristics in one or more of the following groups: race, disability, sex, age, religion or belief, sexual orientation, pregnancy and maternity and gender reassignment. These groups are called protected strands or characteristics : Age: A person belonging to a particular age (e.g. 32 year olds) or range of ages (e.g. 18 – 30 year olds). Disability: A person has a disability if s/he has a physical or mental impairment which has a substantial and long- term adverse effect on that person’s ability to carry out normal day-to-day activities. -

Inclusion Not Exclusion LGBT+ Educators Celebrate Pride

Here’s rooking at you, kid Why the menopause matters UK Disability History Month The many benefits of teaching 75% of members are women; our Disabled leaders’ struggle children chess. See page 19. toolkit is here to help. See page 26. for equality. See page 28. September/ October 2019 Your magazine from the National Education Union Inclusion not exclusion LGBT+ educators celebrate Pride TUC best membership communication print journal 2019 aqa.org.uk/apply Applications are open for 01483 556 161 GCSE and A-level examiners. [email protected] Apply now for summer 2020. AQA13097 Century 230x297.indd 1 14/08/2019 15:56 Educate September/October 2019 Welcome NEU members gather for London Pride. Photo: Jess Hurd Here’s rooking at you, kid Why the menopause matters UK Disability History Month The many benefits of teaching 75% of members are women; our Disabled leaders’ struggle children chess. See page 19. toolkit is here to help. See page 26. for equality. See page 28. THERE is a lot for National Education Union (NEU) members to get their teeth into in this edition of Educate. September/ October 2019 The Government’s determination, after its last failed attempt, to reintroduce a Baseline test for four-year-olds is examined in Your magazine from the National Education Union new research commissioned by the More Than A Score coalition, of which the union is a member. Most school leaders remain opposed to Baseline testing for a variety of reasons borne out of their professional knowledge and expertise. The NEU believes that their voices, and those of other education professionals, who actually know how four-year-olds think and behave, should be listened to and that the Government should Inclusion not give up trying to impose a Baseline test on unwilling schools. -

LGBT+ Legal & Historical Timeline

Care Under the Rainbow LGBT+ Legal & Historical Timeline Ancient Attitudes Ancient attitudes towards sex and gender have been different and varied throughout history. Some religions have viewed sex as being only for procreation. The 19th Century saw the invention of heterosexuality and homosexuality. 19th Century - Criminalisation of Male Homosexuality The last two men to be executed for homosexual acts were James Pratt and John Smith on 27 November 1835. In 1861 the Offences Against the Person Act abolished the death penalty for homosexual acts. In 1885 ‘Gross Indecency’, defined as ‘any sexual activity between males’, became a crime under the Criminal Law Amendment Act. In 1895 Oscar Wilde, the famous poet and playwright, was sentenced to two years hard labour for gross indecency. 1921 - Criminalisation of Lesbianism In 1921 gross indecency was set to be extended to sexual acts between women. The Houses of Parliament rejected this on the grounds most women were not aware of lesbianism and the Act may have actively encouraged women to explore their sexuality. 1957 - Wolfenden Report In 1957 the Wolfenden Report was published after a succession of high profile convictions for gross indecency. The report called for the partial decriminalisation of male homosexuality. https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/private-lives/ relationships/collections1/sexual-offences-act-1967/wolfenden-report-/ 1967 - Decriminalisation of Male Homosexuality Male homosexuality was decriminalised in England and Wales in 1967, under the Sexual Offences Act. This Act led to the partial decriminalisation of sex between men. This was followed by decriminalisation of homosexuality in Scotland in 1980 and in Northern Ireland in 1982. -

Presentation

Housekeeping •Please mute your mic during the talk •There will be time at the end for discussion, publically or privately •This session will be recorded •Slides and recording will be available after •Follow on twitter @equal4success Queer scientists through history Elizabeth Wynn She/her 19/11/2020 The Great Geysers of California by Laura De Force Gordon If this little book should see the light after its 100 years of entombment, I would like its readers to know that the author was a lover of her own sex and devoted the best years of her life in striving for the political equality and social and moral elevation of women. Wouldn’t it be wonderful if all our letters could be published in the future in a more enlightened time. Then all the world could see how in love we are. Gordon Bowsher to Gilbert Bradley, 1940s James Barry • c. 1789 – 25 July 1865 • Irish surgeon • Qualified as a doctor in 1812 and joined the British army the following year • Served in many parts of the British Empire including South Africa, Jamaica, Malta and Canada where he promoted sanitation and nutritional reforms for troops and local residents • Performed one of the first recorded successful Caesarean sections outside of Europe James Barry • He was named Margaret Ann Bulkley at birth and was known as female in childhood • He changed his name before university and lived as a man for the rest of his life • Despite requesting “in the event of his death, strict precautions should be adopted to prevent any examination of his person”, the woman laying out the body described him as ‘a perfect female’ • The doctor who signed the death certificate wrote, “it was none of my business whether Dr Barry was a male or a female, and I thought she might be neither, viz. -

LGBTQ+ History Month 2021 Events, Information & Resources

LGBTQ+ History Month 2021 Events, Information & Resources Knowledge is power and with this month being LGBTQ+ History Month we want to highlight the various resources and fantastic content that celebrates and educates LGBTQ+ History Month. In partnership with our friends at Outhouse East Colchester & Colchester Pride we’ve highlighted various opportunities, information & resources for students, teachers, businesses & home-schooling parents. Why Do We Celebrate LGBTQ+ Pride? What is LGBTQ+ Pride? Pride events take place every year to celebrate the LGBTQ+ community both locally and around the world. Most towns and cities now have some form of Pride event, which are often made up of parades and festivals. Pride is an opportunity for people from the LGBTQ+ community, plus their allies, to come together to celebrate but also to be visible. Pride started as a protest, and in a world where prejudice against LGBTQ+ people still exists, that element is still very important in modern Pride events. Often Pride events will take place in June, which is recognised as Pride month to honour the Stonewall Riots. The Stonewall Riots The Stonewall Riots were a series of demonstrations by members of the LGBTQ+ community in response to a police raid of the Stonewall Inn in Manhattan which took place in the early hours of 28th June 1969. Raids like this were not uncommon, but on this occasion the community decided to fight back when the police became violent towards them. The demonstrations lasted a few days and are now considered to be one of the key moments in the fight for LGBTQ+ equality. -

Introduction

By what process of becoming did I myself finally appear in the world? Introduction “If you think this is going to be a history lesson, you’ve come to the wrong place.” Or, so says Christopher Morcom at the start of our play. This Actor Packet is the history lesson to accompany Single Carrot’s 2019 production of Pink Milk by Ariel Zetina, directed by Ben Kleymeyer. Here you will find information about the life and work of Alan Turing; elaborations on his relationships with Christopher Morcom, Joan Clarke, Arnold Murray and his parents; and an immersive look into the world in which Alan lived. Comments from me, your dramaturg, are throughout to offer connections between this biographical survey and the text of our play. While Pink Milk is not a history lesson, connecting the journey within the play to the rich facts of Alan’s life can help us map out “the process of becoming” by which Alan the man and Alan the character “finally appear” in both the world we live in and the world we’re creating. Please, feel free to reach out to me any time with questions, research requests, or conversations about what you read here. Thank you for letting me be part of your process of becoming. Many Thanks, Abby NOTES: Photo captions are in the alt-text for each photo. Hover over the photo to read the caption. AT:TE is for Alan Turing: The Enigma by Andrew Hodges; TMWKTM is for The Man Who Knew Too Much by David Leavitt. 1 Table of Contents Introduction Table of Contents Alan Turing Biography Additional Resources Alan Turing Biography Timeline Other Characters Christopher Morcom Mr. -

BILLIE JEAN KING Is an American Former World I

BILLIE JEAN KING is an American former World I Number One tennis player. She c o was one of the first prominent n s : openly lesbian athletes, and W h o advocated for gender equality M throughout her career. She is a d e perhaps most remembered for L G her 1973 match against former B T men's champion Bobby Riggs, H i s t o which became known as the r "Battle of the Sexes". After y publicly daring King to play him, she defeated Riggs in the match - which was viewed by an audience of 90 million. King is still regarded as one of the greatest tennis players of all time. VIRGINIA WOOLF was a British essayist, novelist I and literary critic - born in c o London in 1882 - who is today n s : regarded as one of the iconic W h o literary figures of the 20th M Century. She was a founding a d e member of the Bloomsbury L G Group: writers and intellectuals B T whose works influenced modern H i s t o attitudes towards feminism and r sexuality. Woolf openly y discussed the rights of women, also known for her open contribution to mental health visibility. In 1922, Woolf met and began an intimate affair with Vita Sackville-West. Their love letters have since been published. SALLY RIDE was an American astronaut and I engineer, who became the first c o American woman, the youngest n s : American astronaut, and the first W h o known lesbian or gay astronaut M to travel to space in 1983.