Australian Community Broadcasting Hosts a Quiet Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Girls to the Mic 2014 PDF.Pdf

Girls To The Mic! This March 8 it’s Girls to the Mic! In an Australian first, the Community Broadcasting Association of Australia’s Digital Radio Project and Community Radio Network are thrilled to be presenting a day of radio made by women, to be enjoyed by everyone. Soundtrack your International Women’s Day with a digital pop up radio station in Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Adelaide and Perth, and online at www.girlstothemic.org. Tune in to hear ideas, discussion, storytelling and music celebrating women within our communities, across Australia and around the world. Set your dial to Girls to the Mic! to hear unique perspectives on women in politics on Backchat from Sydney’s FBi Radio, in our communities with 3CR’s Women on the Line, seminal women’s music programming from RTR’s Drastic on Plastic from Perth, and a countdown of the top women in arts and culture from 2SER’s so(hot)rightnow with Vivid Ideas director Jess Scully. We’ll hear about indigenous women in Alice Springs with Women’s Business, while 3CR’s Accent of Women take us on an exploration of grassroots organising by women around the world. Look back at what has been a phenomenal year for women and women’s rights, and look forward to the achievements to come, with brekkie programming from Kulja Coulston at Melbourne’s RRR and lunchtime programming from Bridget Backhaus and Ellie Freeman at Brisbane’s 4EB, and an extra special Girls Gone Mild at FBi Radio celebrating the creative, inspiring and world changing women who ought to dominate the airwaves daily. -

Annual Report 2019-20

ANNUAL REPORT 2019-20 Photographer: Martin Philbey CONTENTS About Us 03 Chair’s Report 04 Chief Executive Officer’s Report 06 Treasurer’s Report 08 Mission Statement and Vision 10 Three Year Strategy 11 Music Victoria Advocacy 14 Advisory Panels 15 Victorian Music Development Office 16 Professional Development Program 18 Music Victoria Awards 2019 19 Live Music Professionals 20 Cultivate 22 Music Victoria Board Members 24 Music Victoria Staff 27 Sponsorship and Partners 30 Financial Report 31 Page 02 ABOUT US Contemporary Music Victoria Inc. (Music Victoria) The organisation is governed by a volunteer Board is an independent, not-for-profit organisation and of Directors comprising of 6 members elected the state peak body for contemporary music. by members of Music Victoria, and 3 appointed members by the Board. Music Victoria operates It represents musicians, venues, music businesses under its Rules of Association, updated on 22 and professionals, and music lovers across the October 2019. contemporary Victorian music community. Music Victoria provides advocacy on behalf of the music sector, actively supports the development of the Victorian music community, and celebrates and promotes Victorian music. Photographer: Josh Brnjac Page 03 CHAIR’S REPORT SALLY HOWLAND music venues. The result, as referred to in Patrick’s report, was a significant investment from Creative Victoria who readily understand the central importance of safeguarding live music. Never before has the economic, social and cultural impact of music been so profoundly evident. Our second response was to offer free membership. Whilst this meant a hit to our budget, the Board took the view that offering a connection, a sense of belonging and support to the industry was of paramount importance. -

Music on PBS: a History of Music Programming at a Community Radio Station

Music on PBS: A History of Music Programming at a Community Radio Station Rochelle Lade (BArts Monash, MArts RMIT) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2021 Abstract This historical case study explores the programs broadcast by Melbourne community radio station PBS from 1979 to 2019 and the way programming decisions were made. PBS has always been an unplaylisted, specialist music station. Decisions about what music is played are made by individual program announcers according to their own tastes, not through algorithms or by applying audience research, music sales rankings or other formal quantitative methods. These decisions are also shaped by the station’s status as a licenced community radio broadcaster. This licence category requires community access and participation in the station’s operations. Data was gathered from archives, in‐depth interviews and a quantitative analysis of programs broadcast over the four decades since PBS was founded in 1976. Based on a Bourdieusian approach to the field, a range of cultural intermediaries are identified. These are people who made and influenced programming decisions, including announcers, program managers, station managers, Board members and the programming committee. Being progressive requires change. This research has found an inherent tension between the station’s values of cooperative decision‐making and the broadcasting of progressive music. Knowledge in the fields of community radio and music is advanced by exploring how cultural intermediaries at PBS made decisions to realise eth station’s goals of community access and participation. ii Acknowledgements To my supervisors, Jock Given and Ellie Rennie, and in the early phase of this research Aneta Podkalicka, I am extremely grateful to have been given your knowledge, wisdom and support. -

COMMUNITY RADIO NETWORK PROGRAMS and CONTENT LIST - Content for Broadcast on Your Station

COMMUNITY RADIO NETWORK PROGRAMS AND CONTENT LIST - Content for broadcast on your station May 2019 All times AEST/AEDT CRN PROGRAMS AND CONTENT LIST - Table of contents FLAGSHIP PROGRAMMING Beyond Zero 9 Phil Ackman Current Affairs 19 National Features and Documentary Bluesbeat 9 Playback 19 Series 1 Cinemascape 9 Pop Heads Hour of Power 19 National Radio News 1 Concert Hour 9 Pregnancy, Birth and Beyond 20 Good Morning Country 1 Contact! 10 Primary Perspectives 20 The Wire 1 Countryfolk Around Australia 10 Radio-Active 20 SHORT PROGRAMS / DROP-IN Dads on the Air 10 Real World Gardener 20 CONTENT Definition Radio 10 Roots’n’Reggae Show 21 BBC World News 2 Democracy Now! 11 Saturday Breakfast 21 Daily Interview 2 Diffusion 11 Service Voices 21 Extras 1 & 2 2 Dirt Music 11 Spectrum 21 Inside Motorsport 2 Earth Matters 11 Spotlight 22 Jumping Jellybeans 3 Fair Comment 12 Stick Together 22 More Civil Societies 3 FiERCE 12 Subsequence 22 Overdrive News 3 Fine Music Live 12 Tecka’s Rock & Blues Show 22 QNN | Q-mmunity Network News 3 Global Village 12 The AFL Multicultural Show 23 Recorded Live 4 Heard it Through the Grapevine 13 The Bohemian Beat 23 Regional Voices 4 Hit Parade of Yesterday 14 The Breeze 23 Rural Livestock 4 Hot, Sweet & Jazzy 14 The Folk Show 23 Rural News 4 In a Sentimental Mood 14 The Fourth Estate 24 RECENT EXTRAS Indij Hip Hop Show 14 The Phantom Dancer 24 New Shoots 5 It’s Time 15 The Tiki Lounge Remix 24 The Good Life: Season 2 5 Jailbreak 15 The Why Factor 24 City Road 5 Jam Pakt 15 Think: Stories and Ideas 25 Marysville -

Reclink Annual Report 2017-18

, Annual Report 2017-18 Partners Our Mission Respond. Rebuild. Reconnect. We seek to give all participants the power of purpose. About Reclink Australia Reclink Australia is a not-for-profit organisation whose aim is to enhance the lives of people experiencing disadvantage or facing significant barriers to participation, through providing new and unique sports, specialist recreation and arts programs, and pathways to employment opportunities. We target some of the community’s most vulnerable and isolated people; at risk youth, those experiencing mental illness, people with a disability, the homeless, people tackling alcohol and other drug issues and social and economic hardship. As part of our unique hub and spoke network model, Reclink Australia has facilitated cooperative partnerships with a membership of more than 290 community, government and private organisations. Our member agencies are committed to encouraging our target population group, under-represented in mainstream sport and recreational programs, to take that step towards improved health and self-esteem, and use Reclink Australia’s activities as a means of engagement for hard to reach population groups. Contents Our Mission 3 State Reports 11 About Reclink Australia 3 AAA Play 20 Why We Exist 4 Reclink India 22 What We Do 5 Art Therapy 23 Delivering Evidence-based Programs 6 Events, Fundraising and Volunteers 24 Transformational Links, Training Our Activities 32 and Education 7 Our Members 34 Corporate Governance 7 Gratitude 36 Founder’s Message 8 Our National Footprint 38 Improving Lives and Reducing Crime 9 Reclink Australia Staff 39 Community Partners 10 Contact Us 39 Notice of 2017 Annual General Meeting The Annual General Meeting for Members 1. -

Griffith University Centre for Public Culture and Ideas

Submission 89 GRIFFITH UNIVERSITY CENTRE FOR PUBLIC CULTURE AND IDEAS TUNING IN TO COMMUNITY BROADCASTING SUBMISSION TO THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES STANDING COMMITTEE ON COMMUNICATIONS, INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY AND THE ARTS 23 MARCH 2006 CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2. Culture, Commitment, Community: Looking at the stations 2.1 Scope of the study 2.2 Key findings 2.2.1 Metropolitan and regional stations 2.2.2 Indigenous and ethnic stations 2.2.3 Training 3. Qualitative Audience Research Project, Australia Talks Back 3.1 Scope of the study 3.2 Preliminary Findings of Audience-Based Research 3.2.1 Connecting Communities 3.2.2 Local News and Information 3.2.3 Indigenous Audiences 3.2.4 Ethnic audiences 3.2.5 Community Television 4. Summary and Conclusions REFERENCES APPENDIX A: Schedule of completed metropolitan and regional audience focus groups, and community group interviews Meadows, Forde, Ewart, Foxwell 2 Griffith University Tuning in to community broadcasting 1. Introduction Since 1999, researchers from Griffith University have undertaken national research on Australia’s community broadcasting sector. This research has involved two national projects. The first project (1999-2001) was station-based and was designed to gather data on the sector’s stations and participants. The second study (2003- ), currently underway is an audience-based study which has gathered qualitative data on community broadcasting audiences. This audience study, Australia’s Community Broadcasting Audiences Talk Back, is designed to complement the quantitative study of community broadcasting audiences completed by McNair Ingenuity (2004) and also to complete the circle of community radio stations and their audiences initiated by the first Griffith University study. -

Martin Foley MP

Martin Foley MP Minister for Mental Health GPO 8ox4057 Minister for Equality Melbourne Victoria 3001 Minister for Creative Industries Telephone: +61 3 9096 7500 www.dhhs.vlc.gov.au Ref: BMIN1800492SR Mr Luke Howarth MP Chair of the House Standing Committee on Communications and the Arts CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Mr Howarth INQUIRY INTO THE AUSTRALIAN MUSIC INDUSTRY Thank you for your letter to the Premier of 16 August 2018· about the Parliamentary Inquiry into the Australian Music Industry. Your letter has been referred to me for my consideration and response as the matter you raise falls within my portfolio of responsibilities. On behalf of the State Government of Victoria, I am pleased to make a submission to the Inquiry. The Victorian Government "".'elcomes this inquiry and supports a national, coordinated approach to sustaining the growth of the Australian music industry. Victoria has a demonstrated reputation as a centre of music, with more live music than any other state in Australia and a diverse array of iconic cultural music institutions, as well as supportive music·related laws and strategies. The attached submission describes the Victorian Government's significant investment in the music industry, in particular how Music Works, the Victorian Government's major program commitment, has successfully addressed challenges and opportunities affecting the growth and sustainability of the music industry in this State. Thank you for inviting a submission from the· Victorian Government's and I look forward to hearing the outcomes of this inquiry. ~ rtin Folf MP ~ inister for Creative Industries Date: ~/. {2 .. t_o(r PARLIAMENTARY INQUIRY INTO THE AUSTRALl~N MUSIC INDUSTRY FACTORS CONTRIBUTING TO THE GROWTH AND SUSTAINABILITY OF THE AUSTRALIAN MUSIC INDUSTRY VICTORIAN ,. -

Edition 2017: Lauren Klein, Ken Lim, Campbell Mcnolty, Phoebe Nell-Williams

Edition 2017: Lauren Klein, Ken Lim, Campbell McNolty, Phoebe Nell-Williams 1 | Page Course Outline: Week Content 1 Morning Session - 10:30am - 1pm Module 1 - SYN House ● An introduction to SYN ● Explanation of ‘Make a Thing’ ● Media Law Module 2 - SYN Studios ● Panel operation ● How to plan a radio show ● Audio recording ● Phone interview ● SYN Flagships / Seasonals / Catapults → sign ups! Lunch - 1-2pm Afternoon Session - 2-4pm Module 3 - SYN House ● Live & pre-recorded screen content ● Screen equipment 2 Morning Session - 11am-1pm Module 4 - SYN House ● Audio editing ● Uploading content to the SYN website & Omny Lunch - 1-2pm Afternoon Session - 2-4pm Module 5 - SYN House ● Video editing ● Uploading content to the SYN website & Omny Make a Thing - in brief Before you can become a full SYN volunteer, you have to practise your skills. As part of this course you have to create your own media project. What can I make? Anything you like! We love every kind of media at SYN, here are some ideas to get you started: - Podcast (5 minutes) - Short video (an interview, drama, speech or anything else you like) (2-5 minutes) - Live Radio Program (30 minutes) - Blog post on the SYN website (500 words) - Music radio program (1 hours) - Literally anything else that you want. Put those creative skills to use! When is it due? Two weeks from today. After you finish week 2 of the class you’ll have one more week to finish off your project. Once you’re done, upload your project to the Induction Students Google Drive - https://tinyurl.com/hzym5cc ***SYN STUDIO 1 (TRAINING STUDIO) IS BOOKED FOR SYN INDUCTION EVERY WEDNESDAY 4-6PM*** 2 | Page SYN History: SYN Values: (remember I.P.A.I.D) SYN Media (Student Youth Network Inc.) INNOVATION - SYN celebrates quality, was formed in 2000 as a result of a and supports creativity and flexibility in its merger between two youth radio projects: programming and operations. -

Tuning in to Community Broadcasting

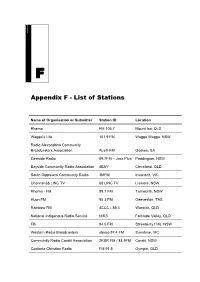

F Appendix F - List of Stations Name of Organisation or Submitter Station ID Location Rhema FM 105.7 Mount Isa, QLD Wagga’s Life 101.9 FM Wagga Wagga, NSW Radio Alexandrina Community Broadcasters Association ALeX-FM Goolwa, SA Eastside Radio 89.7FM – Jazz Plus Paddington, NSW Bayside Community Radio Association 4BAY Cleveland, QLD South Gippsland Community Radio 3MFM Inverloch, VIC Channel 68 LINC TV 68 LINC TV Lismore, NSW Rhema - FM 89.7 FM Tamworth, NSW Huon FM 95.3 FM Geeveston, TAS Rainbow FM 4CCC - 89.3 Warwick, QLD National Indigenous Radio Service NIRS Fortitude Valley, QLD FBi 94.5 FM Strawberry Hills, NSW Western Radio Broadcasters stereo 97.4 FM Sunshine, VIC Community Radio Coraki Association 2RBR FM / 88.9FM Coraki, NSW Cooloola Christian Radio FM 91.5 Gympie, QLD 180 TUNING IN TO COMMUNITY BROADCASTING Orange Community Broadcasting FM 107.5 Orange, NSW 3CR - Community Radio 3CR Collingwood, VIC Radio Northern Beaches 88.7 & 90.3 FM Belrose, NSW ArtSound FM 92.7 Curtin, ACT Radio East 90.7 & 105.5 FM Lakes Entrance, VIC Great Ocean Radio -3 Way FM 103.7 Warrnambool, VIC Wyong-Gosford Progressive Community Radio PCR FM Gosford, NSW Whyalla FM Public Broadcasting Association 5YYY FM Whyalla, SA Access TV 31 TV C31 Cloverdale, WA Family Radio Limited 96.5 FM Milton BC, QLD Wagga Wagga Community Media 2AAA FM 107.1 Wagga Wagga, NSW Bay and Basin FM 92.7 Sanctuary Point, NSW 96.5 Spirit FM 96.5 FM Victor Harbour, SA NOVACAST - Hunter Community Television HCTV Carrington, NSW Upper Goulbourn Community Radio UGFM Alexandra, VIC -

A Handbook for Youth Empowerment Through Media Participation

A Handbook for Youth Empowerment Through Media Participation Based on a project co-designed and co-delivered by the National Ethnic and Multicultural Broadcasters’ Council (NEMBC), The Centre for Multicultural Youth (CMY) and SYN Media in association with Radio Adelaide Training By Rachael Bongiorno from the National Ethnic and Multicultural Broadcasters’ Council 2012. Photo of participants, trainers and project partners in SYN Media studio. All photos in this report were taken by Khalid Omar 2 Introduction Engagement with media is crucial for young people from Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) backgrounds. It provides an opportunity for CALD youth to express themselves in a society in which their perspectives are often marginalised, stereotyped or ignored. This handbook shows you how to develop a training program to equip culturally diverse young people who are not yet involved in broadcasting with the skills, knowledge, enthusiasm and networks for ongoing participation in the media. We particularly want to encourage radio stations to deliver programs like this in collaboration with community organisations servicing migrant and refugee young people. The handbook can also be used by government, community groups and private organisations in the same way. Mercy Ngun Ceu With Australia’s mainstream media, coming into sharp criticism recently for not representing the cultural diversity of this country , training projects such as this are important as ever to diversify media in Australia, increase the number of CALD journalists and provide the public with an understanding of diverse experiences and perspectives. The National Ethnic and Multicultural Broadcasters’ Council (NEMBC) is acutely aware that culturally diverse young people are not just underrepresented in the mainstream media but underrepresented in community broadcasting as well. -

Annual Report 1990-91 AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING TRIBUNAL

AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING TRIBUNAL Annual Report 1990-91 AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING TRIBUNAL ANNUAL REPORT 1990-91 Australian Broadcasting Tribunal Sydney 1991 © Commonwealth of Australia ISSN 0728-8883 Design by Publications and Public Relations Branch, Australian Broadcasting Tribunal. Printed in Australia by Pirie Printers Sales Pty Ltd, Fyshwick, A.CT. 11 CONTENTS 1. Membership of the Tribunal 1 2. The Year in Review 5 3. Powers and Functions of the Tribunal 11 Responsible Minister 14 4. Licensing 15 Number and Type of Licences on Issue 17 Number of Licensing Inquiries 19 Bond Inquiry 19 Commercial Radio Licence Grant Inquiries 20 Supplementary Radio Grant 21 Joined Supplementary /Independent Grant Inquiries 22 Remote Licences 22 Public Radio Licence Grants 23 Licence renewals 27 Renewal of Licences with Conditions 27 Revocation/ Suspension/ Conditions Inquiries 28 Revocation of Licence Conditions 31 Consolidation of Licences 32 Surrender of the 6CI Licence 33 Allocation of Call Signs 33 Changes to the Constituent Documents of Licensees 35 5. Ownership and Control 37 Applications Received 39 Most Significant Inquiries 39 Extensions of Time to Comply with the Act 48 Appointment of Receivers 48 Uncompleted Inquiries 49 Contraventions Amounting To Offences 51 Licence Transfers 52 Uncompleted Inquiries 52 Operation of Service by Other than Licensee 53 Registered Lender and Loan Interest Inquiries 53 6. Program and Advertising Standards 55 Program and Advertising Standards 57 Australian Content (Radio and Television) 58 Compliance with Australian Content Television Standards 60 Children's and Preschool Children's Television Standards 60 Compliance with Children's Television Standards 63 Comments and Complaints 64 Broadcasting of Political Matter 65 Research 66 Ill 7. -

Australian Broadcasting Tribunal Annual Report 1981-82 Annual Report Australian Broadcasting Tribunal 1981-82

AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING TRIBUNAL ANNUAL REPORT 1981-82 ANNUAL REPORT AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING TRIBUNAL 1981-82 Australian Government Publishing Service Canberra 1982 © Commonwealth of Australia 1982 ISSN 0728-606X Printed by Canberra Publishing & Printing Co .. Fyshwick. A.C.T. 2609 The Honourable the Minister for Communications In conformity with the provisions of section 28 of the Broadcasting and Television Act 1942, as amended, I have pleasure in presenting the Annual Report of the Australian Broadcasting Tribunal for the period l July 1981 to 30 June 1982. David Jones Chairman iii CONTENTS PART/ INTRODUCTION Page Legislation 1 Functions of the Tribunal 1 Membership of the Tribunal 1 Meetings of the Tribunal 2 Addresses given by Tribunal Members and Staff 2 Organisation and Staff of the Tribunal 4 Location of the Tribunal's Offices 4 Overseas Visits 5 Financial Accounts of the Tribunal 5 PART II GENERAL Broadcasting and Television Services in operation since 1953 6 Financial results - commercial broadcasting and television stations 7 Fees for licences for commercial broadcasting and television stations 10 Broadcasting and Televising of political matter 13 Political advertising 15 Administration of Section 116(4) of the Act 16 Complaints about programs and advertising 18 Appeals or reviews of Tribunal Decisions and actions by Commonwealth 20 Ombudsman, AdministrativeReview Council and Administrative Appeals Tribunal Reference of questions of law to the Federal Court of Australia pursuant 21 to Section 22B of the Act PART III PUBLIC INQUIRIES