Griffith University Centre for Public Culture and Ideas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Girls to the Mic 2014 PDF.Pdf

Girls To The Mic! This March 8 it’s Girls to the Mic! In an Australian first, the Community Broadcasting Association of Australia’s Digital Radio Project and Community Radio Network are thrilled to be presenting a day of radio made by women, to be enjoyed by everyone. Soundtrack your International Women’s Day with a digital pop up radio station in Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Adelaide and Perth, and online at www.girlstothemic.org. Tune in to hear ideas, discussion, storytelling and music celebrating women within our communities, across Australia and around the world. Set your dial to Girls to the Mic! to hear unique perspectives on women in politics on Backchat from Sydney’s FBi Radio, in our communities with 3CR’s Women on the Line, seminal women’s music programming from RTR’s Drastic on Plastic from Perth, and a countdown of the top women in arts and culture from 2SER’s so(hot)rightnow with Vivid Ideas director Jess Scully. We’ll hear about indigenous women in Alice Springs with Women’s Business, while 3CR’s Accent of Women take us on an exploration of grassroots organising by women around the world. Look back at what has been a phenomenal year for women and women’s rights, and look forward to the achievements to come, with brekkie programming from Kulja Coulston at Melbourne’s RRR and lunchtime programming from Bridget Backhaus and Ellie Freeman at Brisbane’s 4EB, and an extra special Girls Gone Mild at FBi Radio celebrating the creative, inspiring and world changing women who ought to dominate the airwaves daily. -

Tune Into 2020 Victorian Seniors Festival Radio Reimagined Programs

Tune into 2020 Victorian Seniors Festival Radio reimagined programs The Festival has produced more than 80 Also, we are also excited to announce that radio programs in 2020. These programs are 25 Victorian community radio stations are very diverse in nature. They include many airing our programs. For information on your music features, radio plays, spoken word and local broadcaster and where to find them on discussion forums. your radio dial, visit our website at: This active PDF enables you to click at the top www.seniorsonline.vic.gov.au/ of each page to go directly to the relevant festivalsandawards/local-radio-schedule www.seniorsonline page to listen to programs. The categories available to you are: • Music Features • Radio Plays • Spoken Word • Design and Ideas Check out the Festival reimagined website for more great Festival content, leave us a comment, and share with your friends: www.seniorsonline.vic.gov.au/festival Music Features Click here to listen: https://www.seniorsonline.vic.gov.au/festivalsandawards/listen-now/music-features Music and entertainment features from Golden Days Radio Remembering Wireless Music of the 60s Part Two Seniors Dance Hall The Great American Parts 1 & 2 Song Book Featuring the music, popular Old time dance favourites to Remembering the role that culture and history of this sit back and listen to or get up Song and jazz standards from radio has played in our pivotal period. Hosted by Carol and dance along. Hosted by the 20th century performed by lives since the 1930s with Farman. Larry James. some of the greatest singers. a selection of music and Hosted by Peter Thomas. -

Music on PBS: a History of Music Programming at a Community Radio Station

Music on PBS: A History of Music Programming at a Community Radio Station Rochelle Lade (BArts Monash, MArts RMIT) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2021 Abstract This historical case study explores the programs broadcast by Melbourne community radio station PBS from 1979 to 2019 and the way programming decisions were made. PBS has always been an unplaylisted, specialist music station. Decisions about what music is played are made by individual program announcers according to their own tastes, not through algorithms or by applying audience research, music sales rankings or other formal quantitative methods. These decisions are also shaped by the station’s status as a licenced community radio broadcaster. This licence category requires community access and participation in the station’s operations. Data was gathered from archives, in‐depth interviews and a quantitative analysis of programs broadcast over the four decades since PBS was founded in 1976. Based on a Bourdieusian approach to the field, a range of cultural intermediaries are identified. These are people who made and influenced programming decisions, including announcers, program managers, station managers, Board members and the programming committee. Being progressive requires change. This research has found an inherent tension between the station’s values of cooperative decision‐making and the broadcasting of progressive music. Knowledge in the fields of community radio and music is advanced by exploring how cultural intermediaries at PBS made decisions to realise eth station’s goals of community access and participation. ii Acknowledgements To my supervisors, Jock Given and Ellie Rennie, and in the early phase of this research Aneta Podkalicka, I am extremely grateful to have been given your knowledge, wisdom and support. -

Australian Community Broadcasting Hosts a Quiet Revolution

Sounds like a whisper: Australian Community Broadcasting hosts a quiet revolution Author Foxwell-Norton, Kerrie, Ewart, Jacqueline, Forde, Susan, Meadows, Michael Published 2008 Journal Title Westminster Papers in Communication and Culture Copyright Statement © 2008 Westminster Papers in Communication and Culture, University of Westminster, London. The attached file is reproduced here in accordance with the copyright policy of the publisher. Please refer to the journal's website for access to the definitive, published version. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/23018 Link to published version http://www.wmin.ac.uk/mad/page-880 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Sounds like a whisper: Australian Community Broadcasting hosts a quiet revolution Kerrie Foxwell, Jacqui Ewart, Susan Forde and Michael Meadows School of Arts Griffith University Keywords : Audiences, community radio, broadcasting, empowerment, democracy, public sphere. Abstract Recent research into the Australian community broadcasting sector has revealed a developing role for community radio, in particular, in reviving notions of democracy by enhancing public sphere engagement by audiences. This paper is drawn from the first national qualitative audience study of the sector undertaken by the authors and provides strong evidence to suggest listeners are challenging globalised views of the world. They see community radio as ‘theirs’ and the only media able to accurately reflect Australia’s cultural diversity. This is enabling a revival of public sphere activity in the face of restrictions on democracy following an upsurge in global terrorism. We argue that the community broadcasting sector in Australia is providing citizens with services largely ignored by commercial media and to some extent, the publicly-funded Australian Broadcasting Corporation Introduction It’s for us, about us (Focus Group, Roxby Downs ROX FM, 2005). -

NEMBC EB Winter 2003

Winter 2003 Edition oadcasters’ Council National Ethnic and Multicultural Br Special Edition: Youth 2003 Broadcaster Inside: Youth Mini-Conference Ethnic OXYGEN FM: Sharing the Air with You Tongan Youth Radio gets off the ground and When is a survey not a survey? The A radio station of our own: the African community in Australia PRESIDENT’S PEN Contents BIG CHALLENGES AHEAD Ethnic community broadcasters, and 3 Youth Mini-Conference their communities, throughout Australia will be facing some formidable 5 Tongan Youth Radio gets off the ground challenges in the months and year Getting your story into the media ahead: 6 OXYGEN FM: Sharing the Air With You a) the capacity and ability to respond even better to community demands for more and increasingly News You Can Use diverse programming, to meet the needs of the first generation and those of the second and third, as well 7 3ZZZ Youth News as getting on board new and emerging communities 8 Station News within already congested and competing airtime limitations; 2NBC b) but an even bigger and unfortunately threatening 2MCE challenge is the possibility that the 25-year-old 3ZZZ bipartisan political support for modest funding for 6EBA ethnic community broadcasting may be replaced in Radio Adelaide the next triennium by a more “targeted” approach, which will exclude funding for many communities 12 Our own radio station: the African and/or sections within them. community in Australia The non-funding of the AERTP – a most successful and 13 NEMBC welcomes Güler Shaw & Esther economical broadcaster training program – has sent a Anatolitis chilly message as to what kind of weather we are likely to sail into in the immediate future. -

Public Hearings in Melbourne and Alice Springs – 20-21 July Tuning Into Community Broadcasting

MEDIA ALERT Issued: 18 July 2006 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Chair – Jackie Kelly MP STANDING COMMITTEE ON COMMUNICATIONS, Deputy – Julie Owens MP INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY AND THE ARTS Public hearings in Melbourne and Alice Springs – 20-21 July Tuning into community broadcasting The key role that community radio and television broadcasting plays for ethnic, indigenous, vision impaired and regional areas will be discussed during public hearings held in Melbourne (20 July) and Alice Springs (21 July). These are the second hearings for the inquiry into community broadcasting being conducted by the Standing Committee on Communications, Information Technology and the Arts. In Melbourne, the Committee will hear from Channel 31 (C31), which is a not-for-profit television service providing locally-based entertainment, education and information targeting the many diverse communities within Victoria. A number of radio broadcasters will also appear to outline the vital services they provide to communities. Vision Australia operates a network of radio for the print handicapped stations in Victoria and southern NSW. The National Ethnic and Multicultural Broadcasters’ Council is the peak body representing ethnic broadcasters in Australia, and 3ZZZ is Melbourne’s key ethnic community broadcaster. Western Radio Broadcasters operates Stereo 974 FM in Melbourne’s western suburbs and 3KND is Victoria’s only indigenous community broadcaster. In Alice Springs, the Central Australian Aboriginal Media Association operates 8KIN FM, and also a recording studio and television production company. PY Media and the Top End Aboriginal Bush Broadcasting Association assist local and Indigenous groups to develop information services in remote communities. Radio 8CCC is a general community radio station broadcasting to Alice Springs and Tennant Creek in the Northern Territory. -

Tuning in to Community Broadcasting

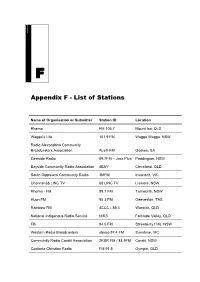

F Appendix F - List of Stations Name of Organisation or Submitter Station ID Location Rhema FM 105.7 Mount Isa, QLD Wagga’s Life 101.9 FM Wagga Wagga, NSW Radio Alexandrina Community Broadcasters Association ALeX-FM Goolwa, SA Eastside Radio 89.7FM – Jazz Plus Paddington, NSW Bayside Community Radio Association 4BAY Cleveland, QLD South Gippsland Community Radio 3MFM Inverloch, VIC Channel 68 LINC TV 68 LINC TV Lismore, NSW Rhema - FM 89.7 FM Tamworth, NSW Huon FM 95.3 FM Geeveston, TAS Rainbow FM 4CCC - 89.3 Warwick, QLD National Indigenous Radio Service NIRS Fortitude Valley, QLD FBi 94.5 FM Strawberry Hills, NSW Western Radio Broadcasters stereo 97.4 FM Sunshine, VIC Community Radio Coraki Association 2RBR FM / 88.9FM Coraki, NSW Cooloola Christian Radio FM 91.5 Gympie, QLD 180 TUNING IN TO COMMUNITY BROADCASTING Orange Community Broadcasting FM 107.5 Orange, NSW 3CR - Community Radio 3CR Collingwood, VIC Radio Northern Beaches 88.7 & 90.3 FM Belrose, NSW ArtSound FM 92.7 Curtin, ACT Radio East 90.7 & 105.5 FM Lakes Entrance, VIC Great Ocean Radio -3 Way FM 103.7 Warrnambool, VIC Wyong-Gosford Progressive Community Radio PCR FM Gosford, NSW Whyalla FM Public Broadcasting Association 5YYY FM Whyalla, SA Access TV 31 TV C31 Cloverdale, WA Family Radio Limited 96.5 FM Milton BC, QLD Wagga Wagga Community Media 2AAA FM 107.1 Wagga Wagga, NSW Bay and Basin FM 92.7 Sanctuary Point, NSW 96.5 Spirit FM 96.5 FM Victor Harbour, SA NOVACAST - Hunter Community Television HCTV Carrington, NSW Upper Goulbourn Community Radio UGFM Alexandra, VIC -

Australian Broadcasting Authority

Australian Broadcasting Authority annual report Sydney 2000 Annual Report 1999-2000 © Commonwealth of Australia 2000 ISSN 1320-2863 Design by Media and Public Relations Australian Broadcasting Authority Cover design by Cube Media Pty Ltd Front cover photo: Paul Thompson of DMG Radio, successful bidder for the new Sydney commercial radio licence, at the ABA auction in May 2000 (photo by Rhonda Thwaite) Printed in Australia by Printing Headquarters, NSW For inquiries about this report, contact: Publisher Australian Broadcasting Authority at address below For inquiries relating to freedom of information, contact: FOi Coordinator Australian Broadcasting Authority Level 15, 201 Sussex Street Sydney NSW 2000 Tel: (02) 9334 7700 Fax: (02) 9334 7799 .Postal address: PO Box Q500 Queen Victoria Building NSW 1230 Email: [email protected] Web site: www.aba.gov.au 2 AustJt"aHan Broadcasting Authority Level 1 S Darling Park 201 Sussex St Sydney POBoxQ500 Queen Victoria Building August 2000 NSW1230 Phone (02) 9334 7700 Fax (02) 9334 7799 Senator the Hon. RichardAlston E-mail [email protected] 'nister for Communications,Information Technology and the Arts DX 13012Marlret St Sydney liarnentHouse anberraACT 2600 In accordancewith the requirements of section 9 andSchedule 1 of the Commonwealth Authorities and Companies Act 1997, I ampleased to present, on behalfof the Members of the AustralianBroadcasting Authority, thisannual reporton the operations of the llthorityfor the year 1999-2000. Annual Report 1999-2000 4 Contents Letter of transmittal 3 Members' report -

Annual Report 1990-91 AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING TRIBUNAL

AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING TRIBUNAL Annual Report 1990-91 AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING TRIBUNAL ANNUAL REPORT 1990-91 Australian Broadcasting Tribunal Sydney 1991 © Commonwealth of Australia ISSN 0728-8883 Design by Publications and Public Relations Branch, Australian Broadcasting Tribunal. Printed in Australia by Pirie Printers Sales Pty Ltd, Fyshwick, A.CT. 11 CONTENTS 1. Membership of the Tribunal 1 2. The Year in Review 5 3. Powers and Functions of the Tribunal 11 Responsible Minister 14 4. Licensing 15 Number and Type of Licences on Issue 17 Number of Licensing Inquiries 19 Bond Inquiry 19 Commercial Radio Licence Grant Inquiries 20 Supplementary Radio Grant 21 Joined Supplementary /Independent Grant Inquiries 22 Remote Licences 22 Public Radio Licence Grants 23 Licence renewals 27 Renewal of Licences with Conditions 27 Revocation/ Suspension/ Conditions Inquiries 28 Revocation of Licence Conditions 31 Consolidation of Licences 32 Surrender of the 6CI Licence 33 Allocation of Call Signs 33 Changes to the Constituent Documents of Licensees 35 5. Ownership and Control 37 Applications Received 39 Most Significant Inquiries 39 Extensions of Time to Comply with the Act 48 Appointment of Receivers 48 Uncompleted Inquiries 49 Contraventions Amounting To Offences 51 Licence Transfers 52 Uncompleted Inquiries 52 Operation of Service by Other than Licensee 53 Registered Lender and Loan Interest Inquiries 53 6. Program and Advertising Standards 55 Program and Advertising Standards 57 Australian Content (Radio and Television) 58 Compliance with Australian Content Television Standards 60 Children's and Preschool Children's Television Standards 60 Compliance with Children's Television Standards 63 Comments and Complaints 64 Broadcasting of Political Matter 65 Research 66 Ill 7. -

CBF Annual Report 2018

Community Broadcasting Foundation Annual Report 2018 Contents Our Vision 2 Our Organisation 3 Community Broadcasting Snapshot 4 President and CEO Report 5 Our Board 6 Our People 7 Achieving our Strategic Priorities 8 Strengthening & Extending Community Broadcasting 9 Content Grants 10 Development & Operational Grants 14 Sector Investment 18 Grants Allocated 21 Financial Highlights 38 Cover: Sandra Dann from Goolarri Media. © West Australian Newspapers Limited. Our thanks to James Walshe from James Walshe photography for his generous support of the CBF in photographing the CBF Board and Support Team. The Community Broadcasting Foundation acknowledges First Nations’ sovereignty and recognises the continuing connection to lands, waters and communities by Traditional Owners of Country throughout Australia. We pay our respects to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures; and to Elders both past and present. We support and contribute to the process of Reconciliation. Annual Report 2018 1 Our Vision A voice for every community – sharing our stories. Wendyll Alec, host of Munda Country Music on Ngaarda Media. Annual Report 2018 2 Community media sits at the From major cities to remote communities, our grants inspire Our Values Our heart of Australian culture, people to create and support local, independent media. Our Values are the cornerstone of our community-based funding helps connect people across the country, including organisation, informing our decision-making and guiding us to Organisation sharing stories, enhancing more than 5.7 million people who tune-in to their local achieve our vision. community radio station each week. health and wellbeing and most Community-minded importantly, helping people find Through broadcasters and with the help of generous We care. -

Tune Into 2020 Victorian Seniors Festival Radio Reimagined Programs

Tune into 2020 Victorian Seniors Festival Radio reimagined programs The Festival has produced more than 80 Also, we are also excited to announce that radio programs in 2020. These programs are 25 Victorian community radio stations are very diverse in nature. They include many airing our programs. For information on your music features, radio plays, spoken word and local broadcaster and where to find them on discussion forums. your radio dial, visit our website at: This active PDF enables you to click at the top www.seniorsonline.vic.gov.au/ of each page to go directly to the relevant festivalsandawards/local-radio-schedule www.seniorsonline page to listen to programs. The categories available to you are: • Music Features • Radio Plays • Spoken Word • Design and Ideas Check out the Festival reimagined website for more great Festival content, leave us a comment, and share with your friends: www.seniorsonline.vic.gov.au/festival Music Features Click here to listen: https://www.seniorsonline.vic.gov.au/festivalsandawards/listen-now/music-features Music and entertainment features from Golden Days Radio Remembering Wireless Music of the 60s Part Two Seniors Dance Hall The Great American Parts 1 & 2 Song Book Featuring the music, popular Old time dance favourites to Remembering the role that culture and history of this sit back and listen to or get up Song and jazz standards from radio has played in our pivotal period. Hosted by Carol and dance along. Hosted by the 20th century performed by lives since the 1930s with Farman. Larry James. some of the greatest singers. a selection of music and Hosted by Peter Thomas. -

Australian Broadcasting Tribunal Annual Report 1981-82 Annual Report Australian Broadcasting Tribunal 1981-82

AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING TRIBUNAL ANNUAL REPORT 1981-82 ANNUAL REPORT AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING TRIBUNAL 1981-82 Australian Government Publishing Service Canberra 1982 © Commonwealth of Australia 1982 ISSN 0728-606X Printed by Canberra Publishing & Printing Co .. Fyshwick. A.C.T. 2609 The Honourable the Minister for Communications In conformity with the provisions of section 28 of the Broadcasting and Television Act 1942, as amended, I have pleasure in presenting the Annual Report of the Australian Broadcasting Tribunal for the period l July 1981 to 30 June 1982. David Jones Chairman iii CONTENTS PART/ INTRODUCTION Page Legislation 1 Functions of the Tribunal 1 Membership of the Tribunal 1 Meetings of the Tribunal 2 Addresses given by Tribunal Members and Staff 2 Organisation and Staff of the Tribunal 4 Location of the Tribunal's Offices 4 Overseas Visits 5 Financial Accounts of the Tribunal 5 PART II GENERAL Broadcasting and Television Services in operation since 1953 6 Financial results - commercial broadcasting and television stations 7 Fees for licences for commercial broadcasting and television stations 10 Broadcasting and Televising of political matter 13 Political advertising 15 Administration of Section 116(4) of the Act 16 Complaints about programs and advertising 18 Appeals or reviews of Tribunal Decisions and actions by Commonwealth 20 Ombudsman, AdministrativeReview Council and Administrative Appeals Tribunal Reference of questions of law to the Federal Court of Australia pursuant 21 to Section 22B of the Act PART III PUBLIC INQUIRIES