Wai 900, A063.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thursday, March 11, 2021 Home-Delivered $1.90, Retail $2.20

TE NUPEPA O TE TAIRAWHITI THURSDAY, MARCH 11, 2021 HOME-DELIVERED $1.90, RETAIL $2.20 PAGE 3 ARTS & ENTERTAINMENT PAGES 23-26 POLICE GISBORNE ACCUSED OF GALLERY ‘RACIALLY CLOSING PROFILING’ ITS DOORS PAGE 10 KIDS INSIDE TODAY CRUISING BACK TO GISBORNE: Eastland Port has 23 cruise ship visits scheduled for next summer, depending on the reopening of New Zealand borders. The Oosterdam (pictured) was a regular visitor to Gisborne in the early years of cruise ship visits here and she will be back twice in early December and early February next summer if the borders reopen. STORY ON PAGE 3 File picture A WOMAN who blew the whistle on Enterprises Limited (BEL) by his Matawai farmer John Bracken’s alleged Gisborne accountant, who unwittingly $17.4 million tax scam has given evidence prepared them using bank transactions in his High Court trial at Gisborne. manipulated by Bracken and false GST Ex-lover a She claimed Bracken was her lover, invoices he submitted. that they lived together in Auckland Bracken’s pleas to the charges have when he was regularly there for been deemed not guilty because he his export business and that she refuses to enter any. He says the charges unknowingly helped him with his scam are not his to answer — that as a by surreptitiously producing false beneficiary of a Maori Incorporation, he is invoices. protected under Te Ture Whenua Maori Bracken did not dispute their Act 1993. woman involvement but in cross-examination of Bracken is representing himself but her conveyed a situation in which she has literacy problems, so is being assisted was a woman scorned who squealed to by his wife and a McKenzie Friend the Serious Fraud Office (SFO) because of (someone who attends court in support her unfulfilled romantic designs on him. -

THE EAST COAST Lingering Incafésorexploringtheregion’S Museums Andarchitecture

© Lonely Planet Publications 362 lonelyplanet.com EAST CAPE •• Pacific Coast Hwy 363 Climate The East Coast basks in a warm, dry climate. THE EAST COAST FACTS The East Coast Summer temperatures around Napier and Eat Macadamia and manuka honey icecream at Gisborne nudge 25°C, rarely dipping below Pacific Coast Macadamias (p366) 5°C in winter. The Hawkes Bay region also Read Witi Ihimaera’s Bulibasha (1994) suns itself in mild, dry grape-growing con- Listen to An aging megastar at the annual Mis- ditions, with an average annual rainfall of sion Concert ( p386 ) 800mm. Heavy downpours sometimes wash Watch Whale Rider (2002), then take the tour ( p373 ) New Zealand is known for its juxtaposition of wildly divergent landscapes but in this region out sections of the Pacific Coast Hwy (SH35) Swim at Tokomaru Bay ( p367 ) it’s the sociological contours that are most pronounced. From the remote villages of East Cape around the Cape. Festival Art-Deco Weekend in Napier and Hast- to Havelock North’s prosperous, wine-stained streets, the East Coast condenses a wide range ings ( p386 ) of authentic Kiwi experiences that anyone with a passion for culture will find fascinating. Getting There & Around Tackiest tourist attraction Napier’s Pania of The region’s only airports are in Gisborne and the Reef statue ( p383 ) If you’re the intrepid sort, you’ll quickly lose the tourist hordes along the Pacific Coast Napier. Air New Zealand flies to both from Go green Knapdale Eco Lodge ( p374 ) Auckland and Wellington, and also to Napier Hwy, on the back roads and obscure beaches of Central Hawkes Bay, or in the mystical from Christchurch. -

AIRPORT MASTER PLANNING GOOD PRACTICE GUIDE February 2017

AIRPORT MASTER PLANNING GOOD PRACTICE GUIDE February 2017 ABOUT THE NEW ZEALAND AIRPORTS ASSOCIATION 2 FOREWORD 3 PART A: AIRPORT MASTER PLAN GUIDE 5 1 INTRODUCTION 6 2 IMPORTANCE OF AIRPORTS 7 3 PURPOSE OF AIRPORT MASTER PLANNING 9 4 REFERENCE DOCUMENTS 13 5 BASIC PLANNING PROCESS 15 6 REGULATORY AND POLICY CONTEXT 20 7 CRITICAL AIRPORT PLANNING PARAMETERS 27 8 STAKEHOLDER CONSULTATION AND ENGAGEMENT 46 9 KEY ELEMENTS OF THE PLAN 50 10 CONCLUSION 56 PART B: AIRPORT MASTER PLAN TEMPLATE 57 1 INTRODUCTION 58 2 BACKGROUND INFORMATION 59 C O N T E S 3 AIRPORT MASTER PLAN 64 AIRPORT MASTER PLANNING GOOD PRACTICE GUIDE New Zealand Airports Association | February 2017 ABOUT THE NZ AIRPORTS ASSOCIATION The New Zealand Airports Association (NZ Airports) is the national industry voice for airports in New Zealand. It is a not-for-profit organisation whose members operate 37 airports that span the country and enable the essential air transport links between each region of New Zealand and between New Zealand and the world. NZ Airports purpose is to: Facilitate co-operation, mutual assistance, information exchange and educational opportunities for Members Promote and advise Members on legislation, regulation and associated matters Provide timely information and analysis of all New Zealand and relevant international aviation developments and issues Provide a forum for discussion and decision on matters affecting the ownership and operation of airports and the aviation industry Disseminate advice in relation to the operation and maintenance of airport facilities Act as an advocate for airports and safe efficient aviation. Airport members1 range in size from a few thousand to 17 million passengers per year. -

Conversion Chart 2020

titirangi gisborne = 130m Can’t make it to town? Climb where you can and convert your maunga! Log your climbs online at www.sportgisborne.org.nz * Permission or safety precautions may be required for the following climbs titirangi 3 climbs manutahi 3 climbs uawa ruatoria Busby’s hill 2 climbs d9 hill 1 climb tokomaru bay tikitiki sugar loaf hilL 1 climb hospital hill 1 climb te puia te araroa hikurangi pou = 7 climbs hut= 8 climbs summit= 13 climbs custom climb For other maunga, use an altimeter app and divide your vertical metres by 130 TITIRANGIMT. EVEREST CHALLENGE 28th september - 15th november support bowel cancer challenge info Bowel Cancer is the second most diagnosed cancer in New Zealand! All donations raised from this The Titirangi Mt. Everest Challenge is a seven week event challenge go to Gisborne East Coast Cancer where people of all ages walk, run or cycle up Titirangi (Kaiti Society. Hill) 68 times, which is equal to the height of Mount Everest. You can do it solo or as part of a team to help motivate each They will ensure this money is used for people other. fighting bowel cancer. To show your support and donate, visit the Sport Gisborne Tairāwhiti website. Participants can track their progress with a free, live, online Thank you! leaderboard to track your (and your team's) progress. Each challenger can create a profile, enter their climbs and track their journey towards summiting Mt. Everest and other noteworthy peaks. It connects friends, whanau and teams, log your climbs which makes it perfect for challenging and encouraging one Track your progress, and the progress of your team another to conquer the maunga! with our live, online leaderboard! Just head to the Sport Gisborne Tairāwhiti website to register, But you don’t need to be in Gisborne to participate. -

Tairawhiti Iwi COVID-19 Response

9 April 2020 Tairawhiti Iwi COVID-19 Response Tena tatou Ngati Porou whanui whanau at home and our health and emergency services. As we countdown to Easter, this weekend being Easter weekend, it is important that we maintain Instead, Facetime your whanau, give them call, vigilance in; ZOOM them to tell them that you love and miss them. Tell them you can have a great catch-up • Staying at home NOHO Ki te KAINGA when we all come out of lock-down • Refrain if not cease all together Tell them to do the right thing for them and the right unnecessary travel including numerous trips to thing by us and that is to stay put. the shops, when one trip should be sufficient Invite them to Join us and 1000 other households • Delegate one person from your bubble to go do in their bubbles for Karakia on Easter Sunday the shop and purchase the household supplies. morning from 11.00am via the link which is on the Te Pihopatanga o Aotearoa FB page We can not stress enough the importance of NOHO https://www.facebook.com/TairawhitiAmorangi KI TE KAINGA WHANAU. Remember whanau, The imposed national Lockdown, which for some of us might have been better as a “LOCKED-IN’ is STAY IN YOUR BUBBLE AND KEEP OUT OF showing promising results, with daily numbers of TROUBLE people testing positive for COVID 19 declining, or at the very leas not rising. While this is still early days, BE KIND TO EACH OTHER, LOOK AFTER ONE it is the right trend and we want to see that ANOTHER continue. -

East Coast Inquiry District: an Overview of Crown-Maori Relations 1840-1986

OFFICIAL Wai 900, A14 WAI 900 East Coast Inquiry District: An Overview of Crown- Maori Relations 1840-1986 A Scoping Report Commissioned by the Waitangi Tribunal Wendy Hart November 2007 Contents Tables...................................................................................................................................................................5 Maps ....................................................................................................................................................................5 Images..................................................................................................................................................................5 Preface.................................................................................................................................................................6 The Author.......................................................................................................................................................... 6 Acknowledgements............................................................................................................................................ 6 Note regarding style........................................................................................................................................... 6 Abbreviations...................................................................................................................................................... 7 Chapter One: Introduction ...................................................................................................................... -

Historic and Notable Trees of New Zealand : Poverty Bay, Hawkes

, ! ,PRODUCTION FORESTRY DIVISION FOREST MENSURATION REPORT NO. 18 (revision) ,,-- ODC 174(931 )--090.2 ~· .soIL BUREAU I . UBRARY I U\NDCARE RESEARCH N?. J P.O. BOX 69, LINCOLN, f<.L NEW ZEALAND FOREST SERVICE f ORE ST RESEARCH INSTITUTE HISTORIC AND NOTABLE TREES OF NEW ZEALAND: EAST COAST - POVERTY BAY, HAWKES BAY i1 'i." S. W. Burstall Forest mensuration report leo (rev) ADDENDUM The following entry should be with Notable Exotic Trees of National Interest in the Rawkes Bay section of this revision. It appeared in that section of the 1970 report. Populus deltoides 'Virginiana', Necklace Poplar. Frimley Park, Hastings. Dbh 262 cm, height 44.3 m, with a clear trunk to 9 m, in 1974. Planted c.1874. This is the largest known deciduous tree in New Zealand and one of the largest poplars in the world. Growth appears to be declining as since 1969 diameter has increased by only 4 cm and there has been little if any·height growth. SOIL BUREAU HISTORIC AND NOTABLE TREES OF NEW ZEALAND: POVERTY BAY, HAWKES BAY S.W. Burstall Date: September 1974 ODC 174(931)~090.2 Forest Mensuration Report No. 18 (revised) Production Forestry Division Forest Research Institute Private Bag Rotorua NEW ZEALAND NOTE: This is an unpublished report, and it must be cited as such, e.g. "New Zealand Forest Service, Forest Research Institute, Forest Mensuration Report No. 18 (revised) 1974 (unpublished)". Permission to use any of its contents in print must first be obtained from the Director of the Production Forestry Division. INTRODUCTION Comments on the early establishment and in New Zealandmostly appeared in letters and journals of military personnel. -

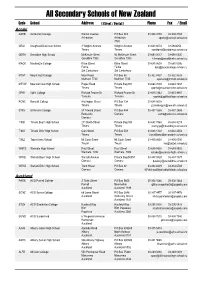

Secondary Schools of New Zealand

All Secondary Schools of New Zealand Code School Address ( Street / Postal ) Phone Fax / Email Aoraki ASHB Ashburton College Walnut Avenue PO Box 204 03-308 4193 03-308 2104 Ashburton Ashburton [email protected] 7740 CRAI Craighead Diocesan School 3 Wrights Avenue Wrights Avenue 03-688 6074 03 6842250 Timaru Timaru [email protected] GERA Geraldine High School McKenzie Street 93 McKenzie Street 03-693 0017 03-693 0020 Geraldine 7930 Geraldine 7930 [email protected] MACK Mackenzie College Kirke Street Kirke Street 03-685 8603 03 685 8296 Fairlie Fairlie [email protected] Sth Canterbury Sth Canterbury MTHT Mount Hutt College Main Road PO Box 58 03-302 8437 03-302 8328 Methven 7730 Methven 7745 [email protected] MTVW Mountainview High School Pages Road Private Bag 907 03-684 7039 03-684 7037 Timaru Timaru [email protected] OPHI Opihi College Richard Pearse Dr Richard Pearse Dr 03-615 7442 03-615 9987 Temuka Temuka [email protected] RONC Roncalli College Wellington Street PO Box 138 03-688 6003 Timaru Timaru [email protected] STKV St Kevin's College 57 Taward Street PO Box 444 03-437 1665 03-437 2469 Redcastle Oamaru [email protected] Oamaru TIMB Timaru Boys' High School 211 North Street Private Bag 903 03-687 7560 03-688 8219 Timaru Timaru [email protected] TIMG Timaru Girls' High School Cain Street PO Box 558 03-688 1122 03-688 4254 Timaru Timaru [email protected] TWIZ Twizel Area School Mt Cook Street Mt Cook Street -

Auckland Regional Office of Archives New Zealand

A supplementary finding-aid to the archives relating to Maori Schools held in the Auckland Regional Office of Archives New Zealand MAORI SCHOOL RECORDS, 1879-1969 Archives New Zealand Auckland holds records relating to approximately 449 Maori Schools, which were transferred by the Department of Education. These schools cover the whole of New Zealand. In 1969 the Maori Schools were integrated into the State System. Since then some of the former Maori schools have transferred their records to Archives New Zealand Auckland. Building and Site Files (series 1001) For most schools we hold a Building and Site file. These usually give information on: • the acquisition of land, specifications for the school or teacher’s residence, sometimes a plan. • letters and petitions to the Education Department requesting a school, providing lists of families’ names and ages of children in the local community who would attend a school. (Sometimes the school was never built, or it was some years before the Department agreed to the establishment of a school in the area). The files may also contain other information such as: • initial Inspector’s reports on the pupils and the teacher, and standard of buildings and grounds; • correspondence from the teachers, Education Department and members of the school committee or community; • pre-1920 lists of students’ names may be included. There are no Building and Site files for Church/private Maori schools as those organisations usually erected, paid for and maintained the buildings themselves. Admission Registers (series 1004) provide details such as: - Name of pupil - Date enrolled - Date of birth - Name of parent or guardian - Address - Previous school attended - Years/classes attended - Last date of attendance - Next school or destination Attendance Returns (series 1001 and 1006) provide: - Name of pupil - Age in years and months - Sometimes number of days attended at time of Return Log Books (series 1003) Written by the Head Teacher/Sole Teacher this daily diary includes important events and various activities held at the school. -

NZAR 15 LEG ONE** WHENUAPAI NZWP To

NZAR 15 LEG ONE** WHENUAPAI NZWP to WHANGAREI NZWR EN-ROUTE INFORMATION ** DARGAVILLE AIRPORT NZDA VISUAL SIGHTING SPRINGFIELD NDB DEPARTURE TIME 0730 LOCAL SEPTEMBER 26 2015 WHENUAPAI AIRPORT INFORMATION RUNWAY 26/08 x 5187 FT 21/03 x 6664 FT 30/12 x 4744 FT ELEVATION 103 FT VOR 108.8 ROUTE INFORMATION After take-off track 300 degrees to Dargaville Airport - Visual Sighting 57 nm Overhead Dargaville Airport track 063 degrees to Springfield NDB 366.0 23 nm Overhead Springfield NDB track 344 degrees to Whangarie 7 nm WHANGARIE AIRPORT INFORMATION RUNWAY 24/06 x 3599 FT ELEVATION 133 FT DME 117.30 NDB 326.0 NZAR 15 LEG TWO ** WHANGAREI to TAURANGA NZTG EN-ROUTE INFORMATION ** GREAT BARRIER NDB MATARANGI AIRPORT NZAG VISUAL SIGHTING PAUANUI BEACH AIRPORT NZUN VISUAL SIGHTING DEPARTURE TIME 1430 LOCAL SEPTEMBER 29 2015 WHANGAREI AIRPORT INFORMATION As per leg one arrival ROUTE INFORMATION After take-off track 100 degrees to Great Barrier NDB 274.0 60 nm Overhead Great Barrier NDB track 144 degrees to Matarangi Airport- Visual Sighting 31 nm Overhead Matarangi Airport track 131 degrees to Pauanui Beach Airport- Visual Sighting 20 nm Overhead Pauanui Beach Airport track 138 degrees to Tauranga 42 nm TAURANGA AIRPORT INFORMATION RUNWAY 25/07 x 6076 FT ELEVATION 13 FT DME 113.20 NDB 304.0 NZAR 15 LEG THREE ** TAURANGA NZTG to GISBORNE NZGS EN-ROUTE INFORMATION ** WHAKATANE NDB DEPARTURE TIME 1300 LOCAL OCTOBER 02 2015 TAURANGA AIRPORT INFORMATION As per leg two arrival ROUTE INFORMATION After take-off track 094 degrees to Whakatane NDB 362.0 -

Monday, September 14, 2020 Home-Delivered $1.90, Retail $2.20 Tears Flow

Nupepa o Te Tairawhiti THE GISBORNE HERALD RĀHINA, MAHURU 9, 2019 I MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 9, 2019 HOME-DELIVERED $1.70, RETAIL $2.00 TE NUPEPA O TE TAIRAWHITI RAHINA, MAHURU 14, 2020 I MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 14, 2020 HOME-DELIVERED $1.90, RETAIL $2.20 TEARS FLOW AT C COMPANY HOUSE PAGE 3 PUKANA: Kereru class students at Te TOLAGA BAY CIVIL DEFENCE PAGE 4 ‘All day, every day, te reo is our way’ Hapara School practise their te reo Maori every day. Te Wiki o te reo Maori VOLUNTEERS RECOGNISED is another week where the students UNHEARDOFSAVINGS! IT is Te Wiki o te reo Maori Ms Neilson said. what they teach us every embrace te ao Maori. The children are (Maori Language Week) but “Singing connects us morning so we will become pictured with teacher Tanya Neilson. te reo Maori is used at Te and brings us together better performers, therefore Picture by Liam Clayton. Hapara School every school and creates memories and incorporating the intrinsic day. memory space in our brains. link to culture and identity PAGES Each day the kereru “We know our students and the essential element 5-8,11, whanau class have the enjoy our morning sessions of whanaungatanga (the 12, 13, 16 same routine of performing and they could independently importance of people and a waiata (song), karakia run it on their own. connectedness),” said Ms (prayer) and haka and “We are a culturally diverse Neilson. HEARING• Mask refusal halts Fullers ferry trip practise use of te reo Maori whanau and celebrate and “The school’s focus this •NEW Political party leader’s Covid theories kupu (words) and commands respect all people.” year has been about creating raising fears for Maori health because that is a part of who Te Hapara has two kapa a sense of belonging and PBL they are as a class, says haka tutors — Papa Pura and we feel that through culture, • Expecting ugly GDP figures for quarter teacher Tanya Neilson. -

New Zealand 16 East Coast Chapter

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd The East Coast Why Go? East Cape .....................334 New Zealand is known for its mix of wildly divergent land- Pacifi c Coast Hwy ........334 scapes, but in this region it’s the sociological contours that Gisborne .......................338 are most pronounced. From the earthy settlements of the Te Urewera East Cape to Havelock North’s wine-soaked streets, there’s a National Park................344 full spectrum of NZ life. Hawke’s Bay ................. 347 Maori culture is never more visible than on the East Coast. Exquisitely carved marae (meeting house complexes) Napier ...........................348 dot the landscape, and while the locals may not be wearing Hastings & Around .......356 fl ax skirts and swinging poii (fl ax balls on strings) like they Cape Kidnappers ......... 361 do for the tourists in Rotorua, you can be assured that te reo Central Hawke’s Bay ......362 and tikangaa (the language and customs) are alive and well. Kaweka & Intrepid types will have no trouble losing the tourist Ruahine Ranges ...........363 hordes – along the Pacifi c Coast Hwy, through rural back roads, on remote beaches, or in the mystical wilderness of Te Urewera National Park. When the call of the wild gives way to caff eine with- Best Outdoors drawal, a fi x will quickly be found in the urban centres of » Cape Kidnappers (p 361 ) Gisborne and Napier. You’ll also fi nd plenty of wine, as the » Cooks Cove Walkway region strains under the weight of grapes. From kaimoana (p 338 ) (seafood) to berry fruit and beyond, there are riches here for everyone.