Ordner, James

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vital Rates, Limiting Factors and Monitoring Methods for Moose in Montana

Vital rates, limiting factors and monitoring methods for moose in Montana Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Grant W-157-R-6 Annual report, September 1, 2018 Nick DeCesare Jesse Newby Research Wildlife Biologist, MFWP Research Technician, MFWP 3201 Spurgin Rd.│Missoula, MT 59804 490 N. Meridian │Kalispell, MT 59901 406-542-5558 │ [email protected] 406-751-4588 │[email protected] State: Montana FUNDING PARTNERS: Agency: Fish, Wildlife & Parks Safari Club International Foundation: Grant: Montana Shiras Moose Study Conservation Grant, FYs 2016–2019 Grant number: W-157-R-6 Time period: 1 July, 2017 – 30 June, 2018 Note: All results should be considered preliminary and subject to change; please contact the authors before citing or referencing these data. 1 | P a g e Background and summary Concern has arisen in recent years over widespread declines of North American moose (Alces alces) populations along the southern extent of their range. Populations in Montana appear to have declined since the 1990’s, as evidenced by aerial survey trends and hunter harvest statistics. While declining populations have clear implications for hunting opportunity, moose management in Montana also suffers from a lack of rigorous data and methods with which to monitor population trends and prescribe actions. In 2013, Montana Fish, Wildlife, & Parks (MFWP) began a 10-year study designed to improve our understanding of: 1) cost-effective means to monitor statewide moose populations, and 2) the current status and trends of moose populations and the relative importance of factors influencing moose vital rates and limiting population growth (including predators, parasites, habitat, and weather). We are using a mechanistic approach to hierarchically assess which factors are drivers of moose vital rates (e.g., adult survival, pregnancy, calf survival), and ultimately which factors are most important to annual growth of moose populations. -

Media Coverage of Oil Sands Pipelines: a Chronological Record of Headlines from 2010 to 2014

Media Coverage of Oil Sands Pipelines: A Chronological Record of Headlines from 2010 to 2014 Oil Sands Research and Information Network School of Energy and the Environment University of Alberta December 2014 Oil Sands Research and Information Network The Oil Sands Research and Information Network (OSRIN) is a university-based, independent organization that compiles, interprets and analyses available knowledge about managing the environmental impacts to landscapes and water affected by oil sands mining and gets that knowledge into the hands of those who can use it to drive breakthrough improvements in regulations and practices. OSRIN is a project of the University of Alberta’s School of Energy and the Environment (SEE). OSRIN was launched with a start-up grant of $4.5 million from Alberta Environment and a $250,000 grant from the Canada School of Energy and Environment Ltd. OSRIN provides: Governments with the independent, objective, and credible information and analysis required to put appropriate regulatory and policy frameworks in place Media, opinion leaders and the general public with the facts about oil sands development, its environmental and social impacts, and landscape/water reclamation activities – so that public dialogue and policy is informed by solid evidence Industry with ready access to an integrated view of research that will help them make and execute environmental management plans – a view that crosses disciplines and organizational boundaries OSRIN recognizes that much research has been done in these areas by a variety of players over 40 years of oil sands development. OSRIN synthesizes this collective knowledge and presents it in a form that allows others to use it to solve pressing problems. -

Congratulations Available Not Valid on Prior Purchases

Tuesday, 1.21.14 ON THE WEB: www.yankton.net the midwest NEWSROOM: RESS AKOTAN [email protected] P D PAGE 7 Arson Suspected In Sioux Falls Fire Nebraska | Decision 2014 SIOUX FALLS (AP) — The people who run the Co-op Natural Foods business in central Sioux Falls say they’ll re- build after a fire that appears to be arson. Domina Seeking Senate Seat No one was injured and nobody was in the building when it burned on Sunday. BY JOSH FUNK and refusal to work to- tor for the impeachment trials of for- The co-op says more than $100,000 in inventory was de- Associated Press gether as citizens cause mer University of Nebraska Regent stroyed. A small amount of money was taken and several our government to shut David Hergert in 2006 and former Attor- fires were set inside the building, which caused extensive OMAHA, Neb. — Omaha lawyer down.” ney General Paul Douglas in 1984. fire and smoke damage. David Domina is planning to run for U.S. Domina is a promi- Johanns decided not to seek re-elec- Board president Alex Halbach they’ll rebuild and re- Senate and give Nebraska Democrats nent lawyer who repre- tion. The race for his seat has already open at the current site or a new location. their first candidate for Republican sents Nebraska attracted four Republicans and one in- The co-op says it has about 2,500 members, but anyone Mike Johanns’ seat. landowners challenging dependent candidate. can shop at the store that does more than $2 million in Democratic Party Chairman Vince Domina the state law that al- The Republicans are Omaha banker business every year. -

FY 2016 and FY 2018

Corporation for Public Broadcasting Appropriation Request and Justification FY2016 and FY2018 Submitted to the Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies Subcommittee of the House Appropriations Committee and the Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies Subcommittee of the Senate Appropriations Committee February 2, 2015 This document with links to relevant public broadcasting sites is available on our Web site at: www.cpb.org Table of Contents Financial Summary …………………………..........................................................1 Narrative Summary…………………………………………………………………2 Section I – CPB Fiscal Year 2018 Request .....……………………...……………. 4 Section II – Interconnection Fiscal Year 2016 Request.………...…...…..…..… . 24 Section III – CPB Fiscal Year 2016 Request for Ready To Learn ……...…...…..39 FY 2016 Proposed Appropriations Language……………………….. 42 Appendix A – Inspector General Budget………………………..……..…………43 Appendix B – CPB Appropriations History …………………...………………....44 Appendix C – Formula for Allocating CPB’s Federal Appropriation………….....46 Appendix D – CPB Support for Rural Stations …………………………………. 47 Appendix E – Legislative History of CPB’s Advance Appropriation ………..…. 49 Appendix F – Public Broadcasting’s Interconnection Funding History ….…..…. 51 Appendix G – Ready to Learn Research and Evaluation Studies ……………….. 53 Appendix H – Excerpt from the Report on Alternative Sources of Funding for Public Broadcasting Stations ……………………………………………….…… 58 Appendix I – State Profiles…...………………………………………….….…… 87 Appendix J – The President’s FY 2016 Budget Request...…...…………………131 0 FINANCIAL SUMMARY OF THE CORPORATION FOR PUBLIC BROADCASTING’S (CPB) BUDGET REQUESTS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2016/2018 FY 2018 CPB Funding The Corporation for Public Broadcasting requests a $445 million advance appropriation for Fiscal Year (FY) 2018. This is level funding compared to the amount provided by Congress for both FY 2016 and FY 2017, and is the amount requested by the Administration for FY 2018. -

KGLT Financial Statements & Auditor's Report

KGLT-FM and Friends of KGLT A Public Telecommunications Entity Operated by the Board of Regents - Montana University System Financial Statements and Supplementary Information Years Ended June 30, 2017 and 2016 Management's Discussion and Analysis As of and for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2017 Celebrating its 50th anniversary this year, Montana State University's KGLTFM ("The Station"), is a college and community radio station with two transmitters and four translators. It is a program of The Associated Students of Montana State University (ASMSU). It is noncommercial, educational, has live announcers, and an open music format. Located on the Bozeman campus, KGLT is licensed to the Board of Regents of the Montana University System. The Station's two transmitters are located in Logan and East Helena, Montana. Additionally, it has four translators that are located in Mammoth Hot Springs, Wyoming and Bozeman, Big Timber, and Livingston, Montana. Known as "alternative public radio in Southwest Montana," KGLT's diverse live shows are played by 90 volunteer announcers trained in nine- week long apprentice classes offered by the station three times per year. KGLT writes and produces approximately 2,000 public service announcements annually, supports local talent, and has an open door policy to the public. KGLT supports local and visiting talent with onair live performances. Local programming is created relevant to community needs and includes Montana Medicine Show, now in its eighth year; fishing, skiing, and avalanche reports; and three community calendars to keep the listeners informed of community events. KGLT also airs national programming that includes This American Life, Studio 360, Mountain Stage, Radiolab, Star Date, and Chrysti the Wordsmith. -

Beau Kilmer 1776 Main Street, P.O

Updated: May 2021 Beau Kilmer 1776 Main Street, P.O. Box 2138 Santa Monica, CA 90407-2138 e: kilmer @ rand dot org p: (310) 393-0411 x6005 twitter: @BeauKilmer EDUCATION Harvard University, Kennedy School of Government/GSAS, Ph.D. in Public Policy, 2007 University of California—Berkeley, Goldman School of Public Policy, M.P.P., 2000 Michigan State University, James Madison College, B.A. with High Honor, 1998 PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE RAND, McCauley Chair in Drug Policy Innovation, Jan 2021—Present RAND, Director of the RAND Drug Policy Research Center, Aug 2019—Present RAND, Senior Policy Researcher, May 2011—Present RAND, Co-Director of the RAND Drug Policy Research Center, Sept 2008—Aug 2019 RAND, Interim Director of RAND San Francisco Bay Area, Aug 2017—Jan 2018; June 2018—Feb 2019 RAND, Full Policy Researcher, May 2009—May 2011 RAND, Associate Policy Researcher, July 2007—May 2009 RAND, Adjunct Staff, May 1997—October 2003; June 2006—July 2007 National Bureau of Economic Research, Research Assistant, Jan 2004—June 2006 Harvard University, Research Assistant, May 2003—Sept 2003 Superior Court of California, San Francisco, Administrative Analyst, Oct 2001—Aug 2002 Netherlands Institute of Mental Health and Addiction, Visiting Scientist, July 2001 AWARDS & FELLOWSHIPS Best Article Award, Journal of Benefit-Cost Analysis, 2019. (Shared with Priscillia Hunt & Jessica Saunders) Distinguished Alumni Award, Oscoda Area High School, 2019 (Inaugural cohort) National Highway Traffic Safety Administration Public Service Award, 2016 “In recognition of your leadership and innovation in the areas of alcohol and drug- impaired driving program and policy research.” Honourable Mention, Behavioural Exchange Award for Outstanding Research, 2015 Awarded to author(s) of an outstanding piece of research in the behavioural sciences in an applied setting. -

Fundraising Banquet Friday, October 20, 2017 Investment Management ®

Massachusetts Family Institute TS FAM ET ILY S IN U S H T C I A T S U S T A E M D Y E L D I I C M A A T F E established E D H T T O 1991 G S N T NI RENGTHE Twenty-Sixth Annual Fundraising Banquet Friday, October 20, 2017 Investment Management ® Breuer & Co. is pleased to support the Massachusetts Family Institute! ® LLC SCHOOL INFORMATION MANAGEMENT www.veracross.com Valetude® LLC HEALTHCARE SOFTWARE & SERVICES www.valetude.com ...providing software and service solutions for education and healthcare; serving organizations seeking highly tailored solutions with extraordinary levels of support. ǻŝŞŗǼȱŘŚŜȬŖŖŗŖȱȱȱȱȱȱȱȱȱŝŖŗȱ ȱǰȱęǰȱȱŖŗŞŞŖȱȱȱȱȱȱȱȱȱ ǯǯ Massachusetts Family Institute Twenty-Sixth Annual Fundraising Banquet Pledge of Allegiance National Anthem Michael Scully Invocation Father Darin Colarusso St. Athanasius Parish Greeting Todd Polando Massachusetts Family Institute Board Member Award Presentation David Aucoin AMEDAL- Asociacion Ministerial Evangelica Del Area de Lawrence Remarks Andrew Beckwith Massachusetts Family Institute President Introduction of Speaker Robert Bradley Massachusetts Family Institute Founder and Vice-Chairman Keynote Address Hugh Hewitt Closing Prayer Pastor Roberto Miranda Congregación León de Judá Dinner music performed by: Barry Johnston and Julianne Johnston 1 Dear Friends of the Family, Welcome to Massachusetts Family Institute’s 26th Anniversary Banquet. As a public policy organization, MFI attributes its success in strengthening families throughout the Commonwealth to the prayers and steadfast support of many partners. Therefore, tonight is a celebration of God’s great faithfulness in answering those prayers and effectively utilizing that support, enabling MFI to be the clarion voice for faith, family and freedom in the Bay State. -

Licensee Count Q1 2019.Xlsx

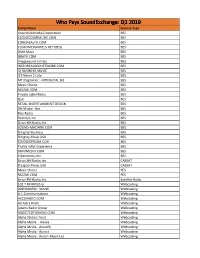

Who Pays SoundExchange: Q1 2019 Entity Name License Type Aura Multimedia Corporation BES CLOUDCOVERMUSIC.COM BES COROHEALTH.COM BES CUSTOMCHANNELS.NET (BES) BES DMX Music BES GRAYV.COM BES Imagesound Limited BES INSTOREAUDIONETWORK.COM BES IO BUSINESS MUSIC BES It'S Never 2 Late BES MTI Digital Inc - MTIDIGITAL.BIZ BES Music Choice BES MUZAK.COM BES Private Label Radio BES Qsic BES RETAIL ENTERTAINMENT DESIGN BES Rfc Media - Bes BES Rise Radio BES Rockbot, Inc. BES Sirius XM Radio, Inc BES SOUND-MACHINE.COM BES Stingray Business BES Stingray Music USA BES STUDIOSTREAM.COM BES Thales Inflyt Experience BES UMIXMEDIA.COM BES Vibenomics, Inc. BES Sirius XM Radio, Inc CABSAT Stingray Music USA CABSAT Music Choice PES MUZAK.COM PES Sirius XM Radio, Inc Satellite Radio 102.7 FM KPGZ-lp Webcasting 999HANKFM - WANK Webcasting A-1 Communications Webcasting ACCURADIO.COM Webcasting Ad Astra Radio Webcasting Adams Radio Group Webcasting ADDICTEDTORADIO.COM Webcasting Aloha Station Trust Webcasting Alpha Media - Alaska Webcasting Alpha Media - Amarillo Webcasting Alpha Media - Aurora Webcasting Alpha Media - Austin-Albert Lea Webcasting Alpha Media - Bakersfield Webcasting Alpha Media - Biloxi - Gulfport, MS Webcasting Alpha Media - Brookings Webcasting Alpha Media - Cameron - Bethany Webcasting Alpha Media - Canton Webcasting Alpha Media - Columbia, SC Webcasting Alpha Media - Columbus Webcasting Alpha Media - Dayton, Oh Webcasting Alpha Media - East Texas Webcasting Alpha Media - Fairfield Webcasting Alpha Media - Far East Bay Webcasting Alpha Media -

Montana Media Outlets

Montana Media Outlets Newswire’s Media Database provides targeted media outreach opportunities to key trade journals, publications, and outlets. The following records are related to traditional media from radio, print and television based on the information provided by the media. Note: The listings may be subject to change based on the latest data. ________________________________________________________________________________ Radio Stations 5. Bigfork Eagle 1. KAAR-FM 6. BILLINGS GAZETTE 2. KATQ-FM [KATQ, The Q] 7. BILLINGS GAZETTE Online 3. KBAZ-FM [The Blaze] 8. Bitterroot Star 4. KBSR-AM [Big Sky Radio] 9. BOZEMAN DAILY CHRONICLE 5. KEMC-FM 10. Bozeman Daily Chronicle Online 6. KENR-FM [107.5 Zoo FM] 11. CARBON COUNTY NEWS 7. KJCR-AM 12. Deseret News 8. KMMR-FM 13. EARTH 9. KMMS-AM 14. Examiner.com - National 10. KMMS-FM [The Moose 95.1] 15. Explore Big Sky 11. KMSO-FM [Mountain FM 102.5] 16. FIELD & STREAM 12. KMXE-FM [FM 99 The Mountain] 17. FLATHEAD BEACON 13. KRVO-FM [The River] 18. FLYFISHER 14. KTHC-FM [Power 95.1] 19. Glacier Reporter 15. KUFM-FM [Montana Public Radio] 20. GLENDIVE RANGER-REVIEW 16. KWMY-FM [My 105.9] 21. Great Falls Tribune 17. KWOL-FM [Kool 105.1] 22. green PROFIT 18. KZMN-FM [The Monster 103.9] 23. Jordan Tribune 19. The Breakfast Flakes - KCTR-FM 24. Liberty County Times 20. The Justin Wayne Show 25. metal underground.com 21. Treasure State Radio Network 26. Miles City STAR 22. Yellowstone Public Radio 27. MISSOULA Independent 28. Missoulian Publication & Print 29. missoulian.com 1. Back Porch View 30. -

CPB-Stabilization-Funding-Request

Corporation for Public Broadcasting Stabilization Funding Request and Justification FY 2021 Submitted to the Office of Management and Budget and to the House and Senate Appropriations Subcommittees on Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies January 26, 2021 Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB) FY 2021 Stabilization Funding Request STATEMENT OF NEED AND REQUEST The Corporation for Public Broadcasting (“CPB”) is very appreciative of the $75 million in stabilization funding in the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (“CARES”) Act of 2020. This financial assistance was vital in providing stability to our nation’s public media system during the early months of the crisis. Today, we request an additional $175 million in stabilization funding to ensure the continued viability of public media stations during this period of extraordinary economic hardship. Although our data indicates that public media’s stabilization needs exceed $400 million, we are mindful of the difficult decisions the new Administration and Congress must make during this time. CPB’s mission is to ensure universal access to high-quality, non-commercial content and telecommunications services that educate, inform and enrich the public. Further, in many states and local communities, public media stations’ digital and broadcast infrastructure provide the backbone for emergency alert, public safety, first responder and homeland security services. If stations are forced to cut additional jobs or further reduce content and services, their -

Poncaexpressgets Newtransitfacility

OMAHA WORLD-HERALD MIDLANDS SATURDAY, MAY 3, 2014 • 5B Obituaries and Funeral Arrangements PoncaExpressgets Guest Book on omaha.com Click Obits BERGIN,JoAnn Ruth Hansen, Marian R. Nielsen, Beverly Ann BUCY,Donald K. Feb 2, 1928 -Apr 28, 2014 Stockton. Preceded in death by hus- (Lamb) CAPPELLANO, Umberto "Al" band Arthur T. Hansen. Survived by Aug 14, 1935 -Apr 30, 2014 newtransitfacility DiDONATO,Charles S. children, Kathy and Bob Tallman, Eliz- Preceded in death by pa- "Chuck" abeth and James Laako, Tom and Lor- rents, Alfred and Enid Lamb and etta Hansen; grandchildren, great brother, Larry Lamb. Survived by hus- BY KATHRYN HARRIS and Norfolk for appointments, DUGGAN,John "Jack" grandchildren, nieces, nephews, many band, John Nielsen; son, David (Susan) GIVENS,Olga M. family and friends. Retired from US Nielsen; daughter, Sally (Dan) Bacon; 6 WORLD-HERALD NEWS SERVICE meetings or gatherings. HANSEN,Marian R. Postal Service, lifelong member of grandchildren; 5great grandchildren; NARFE 1370 and Masonic Narcissus 9siblings; 2sisters in-law and numer- Construction of the HOFFMANN,John T. ous other relatives and friends. In lieu NORFOLK, Neb. — All aboard HORTON,James Madison Chapter 269 Benson. 15,000-square-foot facility start- VISITATIONSunday 3-5pm; FUNERAL of flowers memorials suggested to the the Ponca Express. ed a year ago when a building JACKSON, Michael James SERVICE11am Monday, all at Roeder Alzheimer’s Association Midlands The Ponca Tribe of Nebraska JENKINS,Artree Mortuary. Interment Forest Lawn Chapter. on the Ponca Tribe of Nebraska Cemetery. In lieu of flowers, memori- MEMORIAL SERVICE Monday, May 5, celebrated the completion of KAPPIUS, Sharon A. -

Comments of National Public Radio, Inc

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, DC 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Broadcast Localism ) MM Docket No. 04-233 ) To: The Commission COMMENTS OF NATIONAL PUBLIC RADIO, INC. Neal A. Jackson Vice President for Legal Affairs General Counsel and Secretary Michael Riksen Vice President for Government Relations Dana Davis Rehm Vice President for Member Services Michael Starling Vice President for Engineering Gregory A. Lewis Associate General Counsel Michelle M. Shanahan Associate General Counsel 635 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. Washington, DC 20001 202/513-2040 November 1, 2004 Summary NPR welcomes the Commission's inquiry into broadcast localism because it allows us to address what is a hallmark of public radio -- its inherent localism. As envisioned by Congress and the Commission, public radio is fundamentally a system of locally licensed, locally governed, locally staffed, and locally programmed stations. This inherent localism is directly attributable to a combination of social and institutional forces, many statutorily mandated, such as community advisory boards and open public meetings. In addition, public radio stations are dependent for their existence on voluntary financial contributions from listeners. Indeed, public radio stations continue to thrive due to their deep roots in and ongoing engagement with their communities of service. That public radio has thrived is also a testament to the extensive local services stations provide to communities across the country. Public radio stations serve their communities every day in myriad ways, including through local news and public affairs programming, political programming, support for local arts, culture and non-profit organizations, online and other non- broadcast initiatives, and services specifically targeted to underserved audiences, including the print-impaired and minority listeners.