The Essentials If You Read Nothing Else on Management, Read These Definitive Articles from Harvard Business Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHELSEA, MICHIGAN, WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 16, 1987 24 Pages This Week Suppl«M«Nl

it QUOTE "There is a time to let' 25* things happen and a time to s; make things happen." pvr vopy —Hugh Prather Plus ONE HUNDRED-SEVENTEENTH YEAR—No. 16 CHELSEA, MICHIGAN, WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 16, 1987 24 Pages This Week Suppl«m«nl iW^Pll^ Board of Commissioners f Expected To Approve i Money for Courthouse Washtenaw County Board of Com Tom Freeman, the county's direc "It's a way of giving the township a missioners is expected to give the go- tor of facilities management, said his little something in return," Freeman ahead for the Chelsea district court office would meet with the low bidder, said. 1 house renovation and restoration pro Phoenix Construction Co., late this The initial portion of the renovation ject at its regular meeting tonight. week to firm up a construction work will include removing materials Last Wednesday, Sept. 9 the board's schedule. Freeman anticipated that such as panelized ceilings, and ex Wayj| and Means tommittee ten construction could begin in 30 days, cavation work in the basement. tatively approved the expenditure of probably toward the end of October. When completed, the courthouse an ajdditionar $150,000 to meet the Freeman estimated a construction will have facilities for jury trials higher-t.han anticipated low bid of schedule of 8-10 months. (which now take place in Saline), im $61.5,((00. "If this were a new building on a proved office facilities for support Th^ county had originally budgeted new site, I could tell you pretty ac personnel, handicap access, meeting $330,000 for the project, with the other curately when it would be rooms, and a Washtenaw County publip and private concerns con completed^" Freeman said. -

Updated Record Book 9 25 07.Pmd

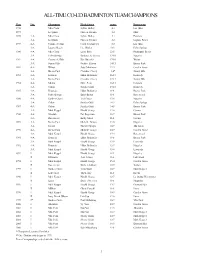

ALL-TIME CO-ED BADMINTON TEAM CHAMPIONS Year Div. Champion Head Coach Score Runner-up 1976 Mira Costa Sylvia Holley 4-1 Los Altos 1977 La Quinta Floreen Fricioni 3-2 Muir 1978 4-A Mira Costa Sylvia Holley 4-1 Estancia 3-A La Quinta Floreen Fricioni 3-2 Laguna Beach 1979 4-A Corona del Mar Carol Stockmeyer 8-5 Los Altos 3-A Laguna Beach Dee Brislen 10-3 Palm Springs 1980 4-A Mira Costa Larry Bark 22-5 Huntington Beach 3-A Palm Springs Barbara Jo Graves 17-10 Nogales 1981 4-A Corona del Mar Kim Duessler 17-10 Walnut 3-A Sunny Hills Pauline Eliason 14-13 Buena Park 1982 4-A Walnut Judy Manthorne 22-5 Garden Grove 3-A Buena Park Claudine Casey 1-0* Sunny Hills 1983 4-A Estancia Lillian Brabander 16-13 Kennedy 3-A Buena Park Claudine Casey 17-12 Sunny Hills 1984 4-A Marina Dave Penn 16-13 Estancia 3-A Colton Sandra Guidi 19-10 Kennedy 1985 4-A Estancia Lillian Brabander 11-8 Buena Park 3-A Palm Springs Daryl Barton 11-8 Rosemead 1986 4-A Garden Grove Vicki Toutz 13-6 Nogales 3-A Colton Sandra Guidi 16-3 Palm Springs 1987 4-A Colton Sandra Guidi 14-5 Buena Park 3-A Mark Keppel Harold George 13-6 Covina 1988 4-A Glendale Pat Rogerson 12-7 Buena Park 3-A Rosemead Kathy Maier 11-8 Covina 1989 4-A Buena Park Michelle Tafoya 13-6 Nogales 3-A Jordan Harriett Sprague 10-9 Alta Loma 1990 4-A Buena Park Michelle Tafoya 10-9 Garden Grove 3-A Mark Keppel Harold George 15-4 Rosemead 1991 4-A Estancia Lillian Brabander 11-8 Buena Park 3-A Mark Keppel Harold George 13-9 Etiwanda 1992 4-A Estancia Lillian Brabander 12-7 Nogales 3-A Mark Keppel Harold George -

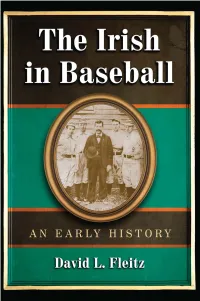

The Irish in Baseball ALSO by DAVID L

The Irish in Baseball ALSO BY DAVID L. FLEITZ AND FROM MCFARLAND Shoeless: The Life and Times of Joe Jackson (Large Print) (2008) [2001] More Ghosts in the Gallery: Another Sixteen Little-Known Greats at Cooperstown (2007) Cap Anson: The Grand Old Man of Baseball (2005) Ghosts in the Gallery at Cooperstown: Sixteen Little-Known Members of the Hall of Fame (2004) Louis Sockalexis: The First Cleveland Indian (2002) Shoeless: The Life and Times of Joe Jackson (2001) The Irish in Baseball An Early History DAVID L. FLEITZ McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Jefferson, North Carolina, and London LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Fleitz, David L., 1955– The Irish in baseball : an early history / David L. Fleitz. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7864-3419-0 softcover : 50# alkaline paper 1. Baseball—United States—History—19th century. 2. Irish American baseball players—History—19th century. 3. Irish Americans—History—19th century. 4. Ireland—Emigration and immigration—History—19th century. 5. United States—Emigration and immigration—History—19th century. I. Title. GV863.A1F63 2009 796.357'640973—dc22 2009001305 British Library cataloguing data are available ©2009 David L. Fleitz. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. On the cover: (left to right) Willie Keeler, Hughey Jennings, groundskeeper Joe Murphy, Joe Kelley and John McGraw of the Baltimore Orioles (Sports Legends Museum, Baltimore, Maryland) Manufactured in the United States of America McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Box 611, Je›erson, North Carolina 28640 www.mcfarlandpub.com Acknowledgments I would like to thank a few people and organizations that helped make this book possible. -

THE WESTFIELD LEADER • the LEADING and MOST WIDELY CIRCULATED WEEKLY NEWSPAPER in UNION COUNTY YEAR—No

THE WESTFIELD LEADER • THE LEADING AND MOST WIDELY CIRCULATED WEEKLY NEWSPAPER IN UNION COUNTY YEAR—No. 48 Published WESTFIELD, NEW JERSEY, THURSDAY, AUGUST 6, 1953 Bvory Thuradn 28 Pages—5 Cent* % Weeks Figures At Chest X-Rays to beJersey Central Takes Steps to Blood Collections Board Appoints Three to aygrounds Set Record Given Free Here Remove Signs at Underpass For Defense Use Teach In Local Schools Monday, Tuesday A minor whirlpool of protest ed as it is at the entrances to one End August 31 was in the making last week when of our town's most complicated Local Badminton Champion To Be civic-minded Weatfielders and oth- street intersections. Second is the McCorison Preaching At Local, State Health ers dedicated to the preservation patriotic angle. The poster in Summer Union Service 3 Elementary of the town's aesthetic values sud- question faces directly tho memo- Local Ambulatory Decided Today at Wilson Field Boards, TB League denly were confronted with two rial monument centrally placed in Donor Program to Join In Survey largo advertising posters at the the Plaza in honor of those who Summer union services, in which Teachers Resign oseph V. Horan, director of recreation for Westfield, has re- Broad street underpnss of the Jer- sacrificed their lives for us in the Function As Usual the Baptist, Congregational and record breaking figures showing enrollment at the end of six (See picture below) sey Central Lines. first World War. Incidentally, it Methodist churches are participat- Report Given On I at the town's playgrounds totaling 1,417. Attendance figures The Board of Health has an- Among the many Westfleld res- also faces one of Wcstfield's larg- The blood for defense program ing, will continue with the wor- 19 771. -

Team History

PITTSBURGH PIRATES TEAM HISTORY ORGANIZATION Forbes Field, Opening Day 1909 The fortunes of the Pirates turned in 1900 when the National 2019 PIRATES 2019 THE EARLY YEARS League reduced its membership from 12 to eight teams. As part of the move, Barney Dreyfuss, owner of the defunct Louisville Now in their 132nd National League season, the Pittsburgh club, ac quired controlling interest of the Pirates. In the largest Pirates own a history filled with World Championships, player transaction in Pirates history, the Hall-of-Fame owner legendary players and some of baseball’s most dramatic games brought 14 players with him from the Louisville roster, including and moments. Hall of Famers Honus Wag ner, Fred Clarke and Rube Waddell — plus standouts Deacon Phillippe, Chief Zimmer, Claude The Pirates’ roots in Pittsburgh actually date back to April 15, Ritchey and Tommy Leach. All would play significant roles as 1876, when the Pittsburgh Alleghenys brought professional the Pirates became the league’s dominant franchise, winning baseball to the city by playing their first game at Union Park. pennants in 1901, 1902 and 1903 and a World championship in In 1877, the Alleghenys were accepted into the minor-league 1909. BASEBALL OPS BASEBALL International Association, but disbanded the following year. Wagner, dubbed ‘’The Fly ing Dutchman,’’ was the game’s premier player during the decade, winning seven batting Baseball returned to Pittsburgh for good in 1882 when the titles and leading the majors in hits (1,850) and RBI (956) Alleghenys reformed and joined the American Association, a from 1900-1909. One of the pioneers of the game, Dreyfuss is rival of the National League. -

Texas Tech Ex-Students Association I April1977

exas Texas Tech Ex- Students Association I April1977 Your gifts to the Texas Tech Loyalty Fund have helped make possible $50,000 in direct funding to Dr. Cecil Mackey, our president for selected Texas Tech programs. My sincere thanks for your support. Because of gifts such as yours, Loyalty Fund contributions in creased some 25% to a record high of $189,000. The average size gift increased to $29.34 as compared to a 1966 average of $9.83. This fine response during 1976 allowed the association to continue its support last year of several Tech programs and allowed the Executive Board at its February 19 meeting to ap prove the $50,000 gift for 1977. Take a look at our progress. During 1976 we began awarding Valedictory Scholarships of which 65 were presented. In addition, we continued to assist in fi nancing the National Merit Scholarship Program at Tech. (As you may recall in 1971 the Association funded this program with an initial gift of$21,000). In addition, 16 other academic, music, band and graduate school scholarships were given. To further promote s tudent participation the Association con tinued financial assistance to the cheerleaders and the School Gifts Make Possible Spirit Committee; provided funds for summer internships for two students in Washington D.C. , and provided expense money Largest, Single for academic recruiting for the University's Admissions Office. University Contribution In addition the Association set up its own academic student recruiting program. We continued our program of awards for the highest ranking graduate, community service, top Techsan staff and Dis tinguished Alumnus Programs. -

New Plan Removes Worst of Altamont Turbines by Ron Mcnicoll in Categories 9 and 10

VOLUME XLVIII, NUMBER 14 Your Local News Source Since 1963 SERVING LIVERMORE • PLEASANTON • SUNOL THURSDAY, APRIL 7, 2011 New Plan Removes Worst of Altamont Turbines By Ron McNicoll in categories 9 and 10. The 10 complete its report on it first. percent reduction in avian mor- the number of birds killed. Regulation of Altamont wind turbines already removed as part The East County Board of tality by November 2009, figured Mike Lynes, conservation turbines, with an eye toward of the swap with ESI were at 8.5 Zoning Adjustments (BZA) on a baseline of 1300 bird deaths director for Golden Gate Audu- reducing bird deaths, has moved and 8.0. unanimously approved the AMP annually, as found in an earlier bon, said, “Overall, we are very ahead. More turbine removal must be at its meeting March 10. That study. The SRC found that the pleased with (the agreement). Twenty-four turbines that completed by Feb. 15, 2012, after date started the clock ticking goal was not met by November The Audubon chapters decided pose the highest risks to raptors an Alameda County-established for the wind-tower removal 2009. to support repowering, provided must be removed by April 25. Scientific Review Committee deadlines. Instead, re-powering the Al- that the new ones are put in with Four high-risk turbines owned (SRC) determines on-the ground The plan resulted from the tamont, by replacing old turbines proper siting, and are moni- by ESI Energy will be kept, in conditions of high-risk turbines settlement of a suit by the Golden with new ones, will be the solu- tored.” Find Out What's exchange for having removed ranked at 8.5. -

Herald 121114 FNL Lorez.Pdf

The Weekly Newspaper of El Segundo Herald Publications - El Segundo, Torrance, Manhattan Beach, Hawthorne, Lawndale, & Inglewood Community Newspapers Since 1911 - (310) 322-1830 - Vol. 103, No. 50 - December 11, 2014 Two Local Food Pantries Inside Supported with Donations This Issue Certified & Licensed Professionals ....................14 Classifieds ...........................4 Crossword/Sudoku ............4 Food ......................................7 Legals ........................... 12,13 Letters ..................................3 Police Reports. ...................3 At a recent check presentation, Chevron El Segundo Firefighters donated $4,000 to two local food pantries. Members from CASE and the Hawthorne Presidents Council were present to receive the donations of $2,000. Pictured (L-R) are Julie Stolnack, Hector Rupitt, Kevin Tovar, Jason Rosander, Alex Monteiro, Robert Garris, Joe Diaz, Father Smith, Stephen Jolley, Polly Price, June Williams, and Cheryl Landreth. Photo courtesy of Chevron. Politically Speaking. ..........5 Real Estate. ...................9-11 El Segundo School Board Selects Sports ............................. 6,16 Jeanie Nishime as New President By Duane Plank sign Challenge, and for the second year in are second to none. These students are truly The only regularly scheduled meeting this a row, advanced to the National Champion- gifted and talented,” and then also gave month for the El Segundo Unified School ships after winning the Independent State praise to Eno and Reed for their work with District school board featured the selection of Challenge. Dubbed the E-Lemon-Ators, the the students. the new board President, and the recognition High School students created an Unmanned Next-up on the presentation agenda was of District students and faculty members who Aerial System to monitor pest infestation in Moore’s entry plan, buoyed by recently com- were recently recognized for receiving the crops. -

History for 2019 Online.Pdf

PITTSBURGH PIRATES TEAM HISTORY ORGANIZATION Forbes Field, Opening Day 1909 The fortunes of the Pirates turned in 1900 when the National 2019 PIRATES 2019 THE EARLY YEARS League reduced its membership from 12 to eight teams. As part of the move, Barney Dreyfuss, owner of the defunct Louisville Now in their 133rd National League season, the Pittsburgh club, ac quired controlling interest of the Pirates. In the largest Pirates own a history filled with World Championships, player transaction in Pirates history, the Hall-of-Fame owner legendary players and some of baseball’s most dramatic games brought 14 players with him from the Louisville roster, including and moments. Hall of Famers Honus Wag ner, Fred Clarke and Rube Waddell — plus standouts Deacon Phillippe, Chief Zimmer, Claude The Pirates’ roots in Pittsburgh actually date back to April 15, Ritchey and Tommy Leach. All would play significant roles as 1876, when the Pittsburgh Alleghenys brought professional the Pirates became the league’s dominant franchise, winning baseball to the city by playing their first game at Union Park. pennants in 1901, 1902 and 1903 and a World championship in In 1877, the Alleghenys were accepted into the minor-league 1909. BASEBALL OPS BASEBALL International Association, but disbanded the following year. Wagner, dubbed ‘’The Fly ing Dutchman,’’ was the game’s premier player during the decade, winning seven batting Baseball returned to Pittsburgh for good in 1882 when the titles and leading the majors in hits (1,850) and RBI (956) Alleghenys reformed and joined the American Association, a from 1900-1909. One of the pioneers of the game, Dreyfuss is rival of the National League. -

Rhythm & Blues...60 Deutsche

1 COUNTRY .......................2 BEAT, 60s/70s ..................69 OUTLAWS/SINGER-SONGWRITER .......23 SURF .............................81 WESTERN..........................27 REVIVAL/NEO ROCKABILLY ............84 WESTERN SWING....................29 BRITISH R&R ........................89 TRUCKS & TRAINS ...................31 INSTRUMENTAL R&R/BEAT .............91 C&W SOUNDTRACKS.................31 POP.............................93 COUNTRY AUSTRALIA/NEW ZEALAND....32 POP INSTRUMENTAL .................106 COUNTRY DEUTSCHLAND/EUROPE......33 LATIN ............................109 COUNTRY CHRISTMAS................34 JAZZ .............................110 BLUEGRASS ........................34 SOUNDTRACKS .....................111 NEWGRASS ........................36 INSTRUMENTAL .....................37 DEUTSCHE OLDIES112 OLDTIME ..........................38 KLEINKUNST / KABARETT ..............117 HAWAII ...........................39 CAJUN/ZYDECO ....................39 BOOKS/BÜCHER ................119 FOLK .............................39 KALENDER/CALENDAR................122 WORLD ...........................42 DISCOGRAPHIES/LABEL REFERENCES.....122 POSTER ...........................123 ROCK & ROLL ...................42 METAL SIGNS ......................123 LABEL R&R .........................54 MERCHANDISE .....................124 R&R SOUNDTRACKS .................56 ELVIS .............................57 DVD ARTISTS ...................125 DVD Western .......................139 RHYTHM & BLUES...............60 DVD Special Interest..................140 -

2015 Spring Premier Prices Realized

2015 Spring Premier Prices Realized Lot # Title Final Price TONY GWYNN'S C.1978-81 SAN DIEGO STATE AZTECS (BASKETBALL) GAME WORN JERSEY AND SHORTS 1 $11,858 (GWYNN FAMILY LOA) TONY GWYNN'S PERSONAL COLLECTION OF ASSORTED LATE 1960'S-EARLY 1970'S FOOTBALL CARDS 2 $710 (GWYNN FAMILY LOA) TONY GWYNN'S 5/20/1973 LONG BEACH KID BASEBALL ASSOCIATION FRAMED ROSTER SHEET INCL. TONY 3 $161 AND HIS BROTHER (GWYNN FAMILY LOA) 4 TONY GWYNN'S LOT OF (61) SIGNED PERSONAL BANK CHECKS FROM 1981-2002 (GWYNN FAMILY LOA) $3,049 TONY GWYNN'S 6/21/1981 AUTOGRAPHED WALLA WALLA PADRES (CLASS A) UNIFORM PLAYER CONTRACT - 5 $6,684 HIS FIRST PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL CONTRACT! (GWYNN FAMILY LOA) TONY GWYNN'S 3/12/1983 AUTOGRAPHED SAN DIEGO PADRES UNIFORM PLAYER'S CONTRACT FOR 1983- 6 $5,020 85 SEASONS (GWYNN FAMILY LOA) TONY GWYNN'S 5/31/1983 AUTOGRAPHED SAN DIEGO PADRES UNIFORM PLAYER'S CONTRACT FOR LAS 7 $799 VEGAS STARS (PCL) REHAB ASSIGNMENT (GWYNN FAMILY LOA) TONY GWYNN'S 25-GAME HIT STREAK BASEBALL FROM 9/14/1983 VS. SF GIANTS OFF MIKE KRUKOW TO 8 $600 BREAK SAN DIEGO PADRES CLUB RECORD OF 22 STRAIGHT (GWYNN FAMILY LOA) TONY GWYNN'S 1984 LOUISVILLE SLUGGER PROFESSIONAL MODEL WORLD SERIES GAME ISSUED BAT 9 $1,805 (GWYNN FAMILY LOA) TONY GWYNN'S PAIR OF 1984 AND MID-1990'S SAN DIEGO PADRES TEAM ISSUED THROWBACK HOME 10 $832 JERSEYS (GWYNN FAMILY LOA) TONY GWYNN'S 1984 SAN DIEGO PADRES NATIONAL LEAGUE CHAMPIONS COMMEMORATIVE BLACK BAT 11 $1,640 PLUS (2) 1998 WORLD SERIES COMMEMORATIVE BATS (GWYNN FAMILY LOA) 12 TONY GWYNN'S 1986 ALL-STAR GAME GIFT KNIFE SET IN -

Wooster, OH), 1948-09-23 Wooster Voice Editors

The College of Wooster Open Works The oV ice: 1941-1950 "The oV ice" Student Newspaper Collection 9-23-1948 The oW oster Voice (Wooster, OH), 1948-09-23 Wooster Voice Editors Follow this and additional works at: https://openworks.wooster.edu/voice1941-1950 Recommended Citation Editors, Wooster Voice, "The oosW ter Voice (Wooster, OH), 1948-09-23" (1948). The Voice: 1941-1950. 175. https://openworks.wooster.edu/voice1941-1950/175 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the "The oV ice" Student Newspaper Collection at Open Works, a service of The oC llege of Wooster Libraries. It has been accepted for inclusion in The oV ice: 1941-1950 by an authorized administrator of Open Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ffI COLLEGE ij TEAM SEND-OF- F FREE SENATE MOVIE FRIDAY . 5 PJU. "SHOE AT THE GYM SHEW 7:30 9:30 I BE THERE ! SCOTT AUDITORIUM Volume LXV WOOSTER, OHIO, THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 23, 1948 Number 1 REPAIRS FORCE DELAYED WELCOME Scot Trustees Add r Holden Evictees Scattered Wide; Hew Hembers Invade Babcock, Annex, Hygeia Benjamin F. Fairless and Charles F. War-Postpon- ed Repairs Near Kettering were elected to the Board of Completion Trustees of the College at the June For the first few days of school, 116 "displaced persons residents meeting of the Board. Mr. Fairless is of Holden Hall, will try college life on a sytsem of crowded conditions president of the United States Steel resulting from delays in the completion of remodeling Corporation. Mr. Kettering, who re operations in their ' ceived an honorary L.