Regional Adaptation Strategies Series -- Okanagan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Riding the Kettle Valley Railway

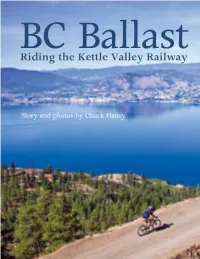

BC Ballast Riding the Kettle Valley Railway Story and photos by Chuck Haney BC Ballast ith chains lubed, tires topped In past cycling trips to the backroads and off with air, and water in the trails of Colorado, Utah, and Oregon, Mike packs, another two-wheeled and I seemed destined to follow a dubious Wadventure was set in motion as the morning pattern of unpredictable weather leading sunlight began to filter through thick stands to various misadventures from incessant of coniferous forest. The cool of the morn- rain, wind, or even snow mucking up our ing air slowly dissipated to the warmth of planned itinerary. Throw in car troubles, a lengthy June summer day. Ravens called tow trucks, raccoons setting off car alarms out to each other from opposing sides of in the middle of the night in a full camp- the trail, their squawking banter and the ground, and getting lost, and it seemed we gravel ballast crunched constantly below had been through it all. But for this particu- our tires. This was the soundtrack of our lar trip, the skies remained clear, the winds first day of riding. In south central British were calm, and even annoying things like Columbia, mighty locomotives were once mosquitoes stayed mostly at bay. the undeniable kings of the Kettle Valley. Our British Columbia adventure on I’m once again paired up with Adventure the KVR began near the remote town of Cyclist editor, Mike Deme, for a cycling Westbridge, which is small enough to be view of the rapids below. For the first excursion in a far-flung location. -

Large Creekfront Acreage Less Than an Hour from Kelowna

® Large Creekfront Acreage Less Than an Hour from Kelowna Sam Hodson Personal Real Estate Corporation www.landquest.com [email protected] (604) 809-2616 ® Marketing British Columbia to the World® “The Source” for Oceanfront, Lakefront, Islands, Ranches, Resorts & Land in British Columbia www.landquest.com www.landquest.com Large Creekfront Acreage Less Than an Hour from Kelowna PROPERTY DETAILS As you drive up Wilkinson Creek FSR Road you’ll see that the property takes in both the north and south side of the valley, with large flat sections with Listing Number: 20242 excellent views on the top of each ridge. The entire Price: $1,995,000 valley bottom is flat and usable with over 2.5 km of creek frontage on Wilkinson Creek. There are Taxes (2020): $7,462.23 literally dozens of potential building sites near the creek for your backcountry getaway. The views Size: 1,655 acres from the upper sections of the property look out over the Kettle River Valley to the south and are Zoning: None quite spectacular. DESCRIPTION Keep in mind this property is located in an area with no zoning, so subdivision, multiple cabins, RV This impressive 1,655 acre property is located sites are all good options for a savvy investor. This less than 70 km from downtown Kelowna and a is one of the largest private land holdings in close 20-minute drive to Big White Ski Resort. After proximity to the Okanagan and your opportunity to turning off Highway 33 acreage begins 1.35 km up take advantage of an emerging trend within British Wilkinson Creek FSR Road and runs along both Columbia with soaring RV popularity and desire sides of the road for the next 3 km to the north for wide open spaces. -

1 Christian Valley Geology

358000m.E. 360000 362000 364000 366000 368000 370000 372000 374000 376000 378000 380000 382000 384000 386000 388000 390000m.E. Big White Mountain Pm CPa 5512000m.N. Pm GEOSCIENCE BC MAP 2017-10 5510000m.N. Jgd GEOLOGY of the 5410000 Goatskin Creek CHRISTIAN VALLEY MAP SHEET KTg 5408000 Eg Pk NTS 082E/10 Mount 5408000 Arthurs SCALE 1:50 000 Qal 0 1 2 3 4 5 5406000 Pk Copper Kettle Creek Ec KILOMETRES Geology and Compilation by Trygve Höy 5406000 GRANBY Pk Cartography by Wayne Jackaman PROVINCIAL Extent of mapping by HÖy and DeFields, 2017 5404000 R e n d e l l C r e e k PARK LEGEND CENOZOIC QUATERNARY ID: 12663 Epm K/Ar 56.3 Qal Alluvium, sand, gravel, till 5404000 Pw MIOCENE/PLIOCENE E R 5402000 Pk KALLIS FORMATION: plateau basalt; black to dark green, fine-grained; locally olivine phyric Pk1 Conglomerate, sandstone, shale Cochrane Creek Mount EOCENE Tanner Ec CORYELL: undifferentiated syenite and monzonite T EL R IV Eg T 5402000 mJg KTg PENTICTON GROUP (Ep): K E Epm MARRON FORMATION: alkali basalt, trachyte; locally amygdaloidal, vesicular or porphyritic; well-banded mafic tuff, blocky tephra; minor black or red shale or slate 5400000 Epm1 UPPER MARRON: basalt Epk KETTLE RIVER FORMATION: basal conglomerate, overlain by feldspathic grit, conglomerate, siltstone and rare shale or argillite; typically light coloured and well bedded 5400000 Trapping Creek Eg Porphyritic granite; coarse-grained with commonly large, pink euhedral K-feldspar crystals Mount Cochrane EOCENE/CRETACEOUS? Pk 5498000 KTg Granite, locally K-feldspar porphyritic; medium -

Kettle River Watershed Analysis Midway, British Columbia to Stream Headwaters

1 Kettle River watershed analysis Midway, British Columbia to stream headwaters Robert Maciak, Trevor Ford, Jenn Schroeder 2 Table of Contents Introduction p. 3 Watershed Description p. 4-10 Issues concerning quality p. 10-13 Issues concerning quantity p. 14-16 Recommendations p. 16 Monitoring strategies p. 18-20 Summary p. 21 References p. 21-22 3 Introduction The Kettle River flows from its headwaters in the Christian Valley, located in the Southern Interior of British Columbia, Canada to the Columbia River in Washington State, USA. We have chosen the drainage upstream of Midway, BC as our sample segment. This is an ideal location for analysis for several reasons: First, the headwaters are located in this area, as are two notable tributaries, the West Kettle River and Boundary Creek; second, the Kettle is a trans-boundary river shared by both Canadian and American riparians and Midway, British Columbia is where the river first crosses the border, making it an important point internationally; third, there are a variety of land use and water quality issues; and finally, Environment Canada has available data sets for the Kettle River at Midway from 1972 to present (BWP Consulting, 2003). Before crossing into the United States, the Kettle River’s resources affect both local riparians as well as visitors. The primary value of the river is irrigation for agricultural purposes. Although, water quality in the river is reported to be excellent, there are concerns of high fluoride levels and increasing levels of fecal coli form (BC Ministry of Environment, 1996). During the summer months the Kettle is used widely by locals and visitors alike for recreational purposes. -

DESTINATION DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY FINTRY Photo: Andrew Strain

OKANAGAN VALLEY DESTINATION DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY FINTRY Photo: Andrew Strain DESTINATION BC Seppe Mommaerts MANAGER, DESTINATION DEVELOPMENT Jonathan Heerema SENIOR PROJECT ADVISOR, DESTINATION DEVELOPMENT [email protected] THOMPSON OKANAGAN TOURISM ASSOCIATION Ellen Walker-Matthews VICE PRESIDENT, DESTINATION & INDUSTRY DEVELOPMENT 250 860 5999 ext. 215 [email protected] MINISTRY OF TOURISM, ARTS, AND CULTURE Amber Mattock DIRECTOR, LEGISLATION AND DESTINATION BC GOVERNANCE 250 356 1489 [email protected] INDIGENOUS TOURISM ASSOCIATION OF BC Greg Hopf INDIGENOUS TOURISM SPECIALIST 250 860 5999 EXT. 208 [email protected] OKANAGAN VALLEY | 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................1 Tourism Strategy II. ACRONYMS ...........................................................................................6 6. A DISTINCTIVE DIRECTION ..........................................................30 a. Vision 1. FOREWORD AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS..............................7 b. Goals 2. INTRODUCING THE STRATEGY .....................................................9 c. Guiding Principles for Destination Development a. Program Vision and Goals d. Motivating Experiences b. Purpose of Strategy e. Development Themes c. A Focus on the Supply and Experience f. Interaction of Development Themes and Motivating Experiences d. Methodology 7. STRATEGIC PRIORITIES .................................................................. 36 e. Project Outputs a. Objectives -

Soil Survey of the Kettle River Valley

SOIL SURVEY of ihe KETTLERIVER VALLEY in the BOUNDARY DISTRICT OF BRITISH COLUMBIA P. N. SPROUT and C. C. KELLEY British Columbia Department of Agriculture Kelowna, B.C. Report No. 9 of the British Columbia Soi1 Survey British Columbia Department of Agriculture sud Research Branch, Canada Department of Agriculture 75402-l ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The British Columbia Department of Agriculture surveyed the soils of the Kettle River valley. The Water Resources Division, Canada Department of Northern Affairs and National Resources, provided financial assistance. The Provincial Department of Lands, Forests and Water Resources supplied base maps and aerial photographs. The Research Branch, Canada Department of Agriculture, Ottawa, prepared the soi1 maps for printing and published the maps and report. The writers wish to acknowledge the contributions of the following surveyors, who assisted in classifying the soils: A. L. van Ryswyk, W. D. Holland, A. B. Dawson, C. H. Brownlee, and M. Schaedle. Dr. J. E. Armstrong and the late Dr. W. E. Cockfield, Geological Survey of Canada, Vancouver, and H. Nasmith, Provincial Department of Mines, Victoria, gave advice on the surface geology of the area. A. McLean, Ecologist, Canada Range Experi- ment Station, Kamloops, prepared the section on native vegetation. Dr. C. A. Rowles, Professor of Soi1 Science, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, J. F. Carmichael, District Agriculturist, Grand Forks, and other officers of the university, and the British Columbia and Canada departments of agri- culture, gave advisory assistance. Dr. J. Baker, Soi1 Survey Branch, Department of Agriculture, Kelowna, supervised the analyses of the soils and assisted in preparing the manuscript. Dr. A. -

Outside Flyer

Weddell Sweaty’s Access To Lake P Vertical Big Smile White Rd Big White Mountain Err 2315 metres Lake to Hwy 6 Big Jaimeson Waterlily White Rd Loop Peak Trail Young Edgewood Spooner CHRISTINA LAKE Lake McCulloch Rd. Hiking Hiking Mountain P (Down hill primary) Hydraulic West Kettle Lake River Fife Haynes Turtle Lake (There’s Willis Lake Worthington Upper Boris FSR Access Rd) Green Tunnel Idabel Falcon Ridge (Both Directions) Lake Hiking Northern Loops 33 Sloan P Mountain Horsefly Rhonda Boris Barge Rd (Down hill primary) Lake Lake O’Leary The Cow Trail Mountain McFarlane Big White Rd Rd Worthington Granby Park FSR P to Big White inset TRANS Wheel Chair Dale Rock Hammer (Down hill primary) CANADA Lake (down hill only) Cedar Boris/WC TRAIL Grove Outflow Hubba Bubba Rhonda Lake Trail Number 7 (Down hill Only) West Kettle Alpine (down hill only) Circuit Burrell Jumpstreet Stump River Meadows Hiking FSR Lake Hiking Gecko (Down hill primary) (down hill) Black Johnsons Graham Worthington Landing FSR FSR Lake Duncan Slabbath Tanner McFarlane South (down hill only) FSR Okanagan Lake Mountain Jump Cr. FSR FSR Pry Bar (down hill only) Trail Upstream CHRISTINA Lower TRANS (Up hill primary) LAKE Barge CANADA P Blue Dot Renata FSR Connetor Lake TRAIL (Both Directions) Trapping Creek FSR Chair Westlake (TNT Arlington Catapult (Down hill Only) Lakes Ranch Lift (down hill only) Dark Arlington Upper Renata FSR Lake FSR Granby West Lake Rd Roast Trail Tenderloin Arlington Mountain Lakes Christina Howard Ace of Creek Trail Lake Dickson’s Lightning Spades -

2016 Geotechnical Annual Report March 31, 2017

Beaverdell Mine 2016 Geotechnical Annual Report March 31, 2017 BEAVERDELL MINE 2016 GEOTECHNICAL ANNUAL REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 3 1.1 Facility Description .............................................................................................. 3 1.2 Mines Act Permit ................................................................................................. 3 2.0 ANNUAL REPORT ......................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Reclamation and Environmental Monitoring ........................................................ 4 2.2 Annual Dam Safety Inspection ............................................................................ 4 2.3 Independent Tailings Review Board .................................................................... 4 2.4 Recommendations from Annual Dam Safety Inspection ..................................... 4 2.5 Performance of High-Risk Dumps ....................................................................... 4 2.6 Updates on Tailings Storage Facilities Register .................................................. 4 2.7 Other Information as Directed by the Chief Inspector .......................................... 5 2.7.1 Summary of Design and Construction Works from the Year .................... 5 2.7.2 Planned Design and Construction Works for Following Year ................... 6 2.7.3 Schedule for the Following -

November 19, 2020 B.C. Sustainable Energy Association C/O William J

Diane Roy FortisBC Vice President, Regulatory Affairs 16705 Fraser Highway Surrey, B.C. V4N 0E8 Gas Regulatory Affairs Correspondence Tel: (604)576-7349 Email: [email protected] Cell: (604) 908-2790 Fax: (604) 576-7074 Electric Regulatory Affairs Correspondence www.fortisbc.com Email: [email protected] November 19, 2020 B.C. Sustainable Energy Association c/o William J. Andrews, Barrister & Solicitor 1958 Parkside Lane North Vancouver, B.C. V7G 1X5 Attention: Mr. William J. Andrews Dear Mr. Andrews: Re: FortisBC Inc. (FBC) Project No. 1598940 Application for Approval of Rate Design and Rates for Electric Vehicle (EV) Direct Current Fast Charging (DCFC) Service – Revised Application dated September 30, 2020 (Revised Application) Response to the B.C. Sustainable Energy Association (BCSEA) Information Request (IR) No. 1 On September 30, 2020, FBC filed the Revised Application referenced above. In accordance with BCUC Order G-254-20 setting out the Regulatory Timetable for the review of the Revised Application, FBC respectfully submits the attached response to BCSEA IR No. 1. If further information is required, please contact the undersigned. Sincerely, FORTISBC INC. Original signed: Diane Roy Attachments cc (email only): Commission Secretary Registered Parties FortisBC Inc. (FBC or the Company) Submission Date: Application for Approval of Rate Design and Rates for Electric Vehicle (EV) Direct November 19, 2020 Current Fast Charging (DCFC) Service (Revised Application) Response to B.C. Sustainable Energy Association (BCSEA) Information Request (IR) Page 1 No. 1 1 1.0 Topic: FBC Public DCFC Deployment 2 Reference: Exhibit B-5, p.10; Table 2-2: FBC DCFC Sites 3 FBC states, “At this time, FBC does not expect to deploy additional sites beyond those 4 detailed below.” Table 2-2: FBC DCFC Sites lists 25 DCFC sites with details 5 corresponding to criteria in section 5 of the GGRR. -

1.0 Title Page Technical Report on Blizzard Uranium

Blizzard Uranium Property, Beaverdell Area, British Columbia 1.0 TITLE PAGE TECHNICAL REPORT ON BLIZZARD URANIUM DEPOSIT BEAVERDELL AREA, BRITISH COLUMBIA, CANADA Greenwood Mining Division NTS 92E/10W-1:50,000 Map Mineral Title Map 82E.066 o o (Centered near: 49 37’27”N, 118 55’14”W) By Peter A. Christopher, PhD, P.Eng. PETER CHRISTOPHER & ASSOCIATES INC. 3707 West 34th Avenue Vancouver, B.C., Canada V6N 2K9 For Santoy Resources Ltd. Suite 611-675 West Hastings Street Vancouver, B.C., Canada V6B 1N2 August 31, 2005 Blizzard Uranium Property, Beaverdell Area, British Columbia 2.0 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 TITLE PAGE............................................................................................................... 1 2.0 TABLE OF CONTENTS.............................................................................................. 2 3.0 SUMMARY.................................................................................................................. 1 3.1 Property Description ............................................................................................................ 1 3.2 Property Location, Infrastructure and Access .................................................................. 1 3.3 Property Ownership ............................................................................................................. 2 3.4 Property Geology and Mineralization ................................................................................ 2 3.5 Deposit Type......................................................................................................................... -

IN CARMI CAMP the Carmi at That Depth

'<ptcfa& # > *•'•?• THE WEST FORK NEWS. 1 Bfe Vol.. I. No, ?. BEAVERDELL, B. C, NOVEMBER 16, 1901. PEH TEAK, $2.00 • ••y*S * • $* gradually widening out and doubtless at the 100-foot level will be as wide as ON THE BOUNTY IN CARMI CAMP the Carmi at that depth. The values in the Butcher Boy are somewhat Rich Strike in the Butcher higher than those of the Carmi. Work Will Be Commenced in Boy Shaft Dr. Mathison, dentist, Naden-Flood o Pew Days block, Greenwood, B. C. GOOD ORE ON JWt CARMI MINING NOTES. SINKING ON THE PROPERTY A. E. Anderson has just completed assessment work on his claims for the In Ihe Carmi Shaft a Very Rich Pay season. He owns the Colbrooke, Colo Contract to be Let This Week for Shoot Was Struck the Past rado Madura and Silent Partner on Sinking One hundred reel •*<' Week at 125 feet. Cranberry creek, and Jo Jo on Wallace and Crosscutting. mountain, all promising claims. On the Colbrooke an open cut 20 feet deep During the past week development and 24 feet long has been made, and Andrew Laid law of Greenwood has work on the Carmi and Butcher Boy frofi! this a tunnel has been run 28 feet. been successful in interesting Chicago | in Carmi camp has uncovered much The ledge is galena, 2% feet wide, and capital in the Bounty, an adjoining better ore than had heretofore been two assays from it ran $85 and $124.96. claim to the Rambler on Wallace moun taken out of either property. The rich On the Colorado Madura a tunnel has tain. -

Geochemical Report on the Beaverdell Project

GEOCHEMICAL REPORT ON THE BEAVERDELL PROJECT GREENWOOD MINING DIVISION BRITISH COLUMBIA NTS 082E 11 Latitude 49° 31’ North -- Longitude 119°02’ West UTM Zone 11, NAD 83 5486400N 353600E Prepared for: INTIGOLD MINES LTD. #314 – 800 West Pender Street, Vancouver, British Columbia, V6C 2V6 BY James Thom, M.Sc. June 18, 2009 Intigold Mines Ltd. – 2009 Assessment Report Page 1 Contents 1.0 SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................... 4 2.0 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................... 6 2.1 Property Description and Location ..................................................................................................... 6 2.2 Access, Climate, Local Resources and Physiography .......................................................................... 6 3.0 HISTORY ................................................................................................................................................ 11 3.1 Regional Exploration History ............................................................................................................. 11 3.2 History of Exploration, Beaverdell Project Claim Groups ................................................................. 11 3.2.1 Mullins Hill Exploration History .................................................................................................. 12 3.2.2 St. John