Across the Himalayan Gap Manichaean Input To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mar 5 – Jun 12 2016

MAR 5 – JUN 12 2016 PRESS Press Contact Rachel Eggers Manager of Public Relations [email protected] RELEASE 206.654.3151 FEBRUARY 25, 2016 JOURNEY TO DUNHUANG: BUDDHIST ART OF THE SILK ROAD CAVES OPENS AT ASIAN ART MUSEUM MAR 5 See the wonders of China’s Dunhuang Caves—a World Heritage site—through the eyes of photojournalists James and Lucy Lo March 5–June 12, 2016 SEATTLE, WA – The Asian Art Museum presents Journey to Dunhuang: Buddhist Art of the Silk Road Caves, an exhibition featuring photographs, ancient manuscripts, and artist renderings of the sacred temple caves of Dunhuang. Selected from the collection of photojournalists James and Lucy Lo, the works are a treasure trove of Buddhist art that reveal a long-lost world. Located at China’s western frontier, the ancient city of Dunhuang lay at the convergence of the northern and southern routes of the Silk Road—a crossroads of the civilizations of East Asia, Central Asia, and the Western world. From the late fourth century until the decline of the Silk Road in the fourteenth century, Dunhuang was a bustling desert oasis—a center of trade and pilgrimage. The original “melting pot” of China, it was a gateway for new forms of art, culture, and religions. The nearly 500 caves found there tell an almost seamless chronological tale of their history, preserving the stories of religious devotion throughout various dynasties. During the height of World War II in 1943, James C. M. Lo (1902–1987) and his wife, Lucy, arrived at Dunhuang by horse and donkey-drawn cart. -

Manichaean Imagery of Christ As God's Right Hand

Manichaean Imagery of Christ as God’s Right Hand Johannes van Oort* University of Pretoria [email protected] Abstract The article examines the conspicuous references to God‘s ‗Right Hand‘ in Manichaeism by analysing texts from both Western and Eastern sources. The analysed texts prove that the eye-catching imagery (directly or indirectly) refers to Christ. Perhaps this imagery of Christ as God‘s Right Hand also had its place in Manichaean art. The article aims to function as background for a subsequent study of Augustine‘s portrayal of Christ as manus or dextera Dei in his Confessions. Keywords Manichaeism – Christology – God‘s Right Hand – imagery – metaphorical language – Manichaean Christian art Introduction The past years have seen an increasing number of studies on Christ in Manichaeism.1 One striking aspect, however, is still to be explored, sc. the * I would like to acknowledge Jason BeDuhn, Zsuzsanna Gulácsi and Anne-Maré Kotzé for their attentive reading of an earlier version of this article. The study was completed with the support of the National Research Foundation (NRF) in South Africa. 1 Apart from overviews in general publications on Manichaeism, the main topical studies include: I. Gardner, ‗The Docetic Jesus—Some Interconnections Between Marcionism, Manichaeism and Mandaeism‘, in: idem (ed.), Coptic Theological Papyri II: Edition, Commentary, Translation, Wien: In Kommission bei Verlag Brüder Hollinek 1988, 57-85; N.A. Pedersen, ‗Early Manichaean Christology, Primarily in Western Sources‘, in: P. Bryder (ed.), Manichaean Studies, Lund: Plus Ultra 1988, 157-190; Gardner, ‗The Manichaean Account of Jesus and the Passion of the Living Soul‘, in: A. -

Manichaean Networks

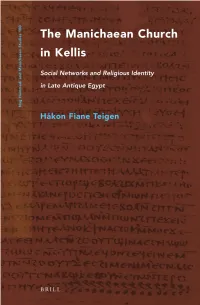

The Manichaean Church in Kellis Nag Hammadi and Manichaean Studies Editors Jason D. BeDuhn Dylan M. Burns Johannes van Oort Editorial Board A. D. Deconick – W.-P. Funk – I. Gardner S. N. C. Lieu – H. Lundhaug – A. Marjanen – L. Painchaud N. A. Pedersen – T. Rasimus – S. G. Richter M. Scopello – J. D. Turner† – F. Wursy Volume 100 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/nhms The Manichaean Church in Kellis By Håkon Fiane Teigen LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Teigen, Håkon Fiane, author. Title: The Manichaean church in Kellis / by Håkon Fiane Teigen. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, [2021] | Series: Nag Hammadi and Manichaean studies, 0929–2470 ; volume 100 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2021008227 (print) | LCCN 2021008228 (ebook) | ISBN 9789004459762 (hardback) | ISBN 9789004459779 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Manichaeism. | Manichaeans—Egypt—Kellis (Extinct city) | Kellis (Extinct city)—Civilization. Classification: LCC BT1410 .T45 2021 (print) | LCC BT1410 (ebook) | DDC 299/.932—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021008227 LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021008228 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. -

Manichaean Art and Calligraphy Art and Calligraphy Played A

Manichaean Art and Calligraphy Art and calligraphyplayed a central role in Manichaeismfrom its inception in S. Baby- lonia in the third century until its final disappearancefrom South China in the sixteenth century. Mani, the founder of the sect, had anticipated the problems which his disciples might encounter in presenting his very graphic teaching on cosmogony to an average audienceby providing them with visual aids in the form of a picture book (Greek/Coptic: Ev'xwv,Middle Persia/Parthian:Ardahang, Chinese: Ta-men-ho-it'u).1 Since Mani had in- tended that the unique revelation he had receivedfrom his Divine Twin should be literally understood, an actual pictorial representationof the myth would serve to guard against al- legoricalinterpretation. The importancegiven to artisticendeavours in the early history of the sect is evident from accounts of its missionary activities. The first Manichaeanmis- sionariesto the Roman Empire were accompaniedby scribes (Middle Persian: dibtrin)and those who went with Mar Ammo to Abar.cahr(the Upper Lands) had among them scribes and a miniature painter / book illuminator (nibegan-nigär).2We also learn from a letter to Mar Ammo from Sisinnios,the archego.rof the sect after the death of Mani, that duplicate copies of the Ardahangwere being made at Merv in Khorasan.3The early Manichaeansalso devel- oped a special Estrangela script from the Aramaic script which was in use in and around Palmyra which gave the Manichaeantexts a unique appearance.This script was used for texts in Syriac, Middle Persian, Parthian, Sogdian and Old Turkish. No copies of the Ardahanghas survived the systematicdestruction of Manichaeanbooks by the sect's many opponents. -

Manichaeism As a Test Case for the Theory of Reception Timothy Pettipiece

Document généré le 29 sept. 2021 15:02 Laval théologique et philosophique A Church to Surpass All Churches Manichaeism as a Test Case for the Theory of Reception Timothy Pettipiece La théorie de la réception Résumé de l'article Volume 61, numéro 2, juin 2005 En vue de tester la viabilité de la théorie de la réception pour l’étude du manichéisme, cette étude examine comment l’effort manichéen d’établir des URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/011816ar liens culturels et linguistiques dans les milieux où s’exerça la mission DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/011816ar manichéenne n’a pas suffi à assurer le maintien de la Religion de Lumière. Le fait que Mani considérait sa révélation comme supérieure aux autres a au Aller au sommaire du numéro contraire empêché sa réception par les cultures chez lesquelles elle voulait être accueillie. Éditeur(s) Faculté de philosophie, Université Laval Faculté de théologie et de sciences religieuses, Université Laval ISSN 0023-9054 (imprimé) 1703-8804 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Pettipiece, T. (2005). A Church to Surpass All Churches : manichaeism as a Test Case for the Theory of Reception. Laval théologique et philosophique, 61(2), 247–260. https://doi.org/10.7202/011816ar Tous droits réservés © Laval théologique et philosophique, Université Laval, Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des 2005 services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. -

The Silk Roads As a Model for Exploring Eurasian Transmissions of Medical Knowledge

Chapter 3 View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE The Silk Roads as a Model for provided by Goldsmiths Research Online Exploring Eurasian Transmissions of Medical Knowledge Views from the Tibetan Medical Manuscripts of Dunhuang Ronit Yoeli-Tlalim At the beginning of the twentieth century, Wang Yuanlu, a Daoist monk in the western frontiers of China accidentally discovered a cave full of manu- scripts near the Chinese town of Dunhuang in Gansu province. The cave, which had been sealed for nearly a thousand years, contained several tons of manuscripts. This cave, now known as Cave 17 or the “library cave,” was sealed in the early eleventh century for reasons that are still being debated by scholars.1 Following this discovery, a race began between the great nations of the time, to acquire as many manuscripts as possible. Today these manuscripts are dispersed among libraries in Paris, London, St. Petersburg, Tokyo, Bei- jing, and elsewhere and are currently being united on the Internet as part of the International Dunhuang Project, based at the British Library.2 The Dunhuang manuscripts are of enormous significance for Buddhist, Central Asian, and Chinese history. Their significance for the history of sci- ence and the history of medicine has only recently begun to be explored in European scholarship by Vivienne Lo, Chris Cullen, Catherine Despeux, Chen Ming, and others.3 Observed in their overall context, the Dunhuang manuscripts are a bit like a time capsule, providing traces of what medicine was like “on the ground,” away from the main cultural centers, at this particu- lar geographical location. -

Coptic Literature in Context (4Th-13Th Cent.): Cultural Landscape, Literary Production, and Manuscript Archaeology

PAST – Percorsi, Strumenti e Temi di Archeologia Direzione della collana Carlo Citter (Siena) Massimiliano David (Bologna) Donatella Nuzzo (Bari) Maria Carla Somma (Chieti) Francesca Romana Stasolla (Roma) Comitato scientifico Andrzej Buko (Varsavia) Neil Christie (Leichester) Francisca Feraudi-Gruénais (Heidelberg) Dale Kinney (New York) Mats Roslund (Lund) Miljenko Jurković (Zagabria) Anne Nissen (Paris) Askold Ivantchik (Mosca) This volume, which is one of the scientific outcomes of the ERC Advanced project ‘PAThs’ – ‘Tracking Papy- rus and Parchment Paths: An Archaeological Atlas of Coptic Literature. Literary Texts in their Geographical Context: Production, Copying, Usage, Dissemination and Storage’, has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 programme, grant no. 687567. I testi pubblicati nella collana sono soggetti a valutazione secondo la procedura del doppio blind referee In copertina: P. Mich. 5421 e una veduta di Karanis © Roma 2020, Edizioni Quasar di Severino Tognon S.r.l. via Ajaccio 41-43, 00198 Roma - tel 0685358444 email: [email protected] eISBN 978-88-5491-058-4 Coptic Literature in Context (4th-13th cent.): Cultural Landscape, Literary Production, and Manuscript Archaeology Proceedings of the Third Conference of the ERC Project “Tracking Papyrus and Parchment Paths: An Archaeological Atlas of Coptic Literature. Literary Texts in their Geographical Context (‘PAThs’)”. edited by Paola Buzi Edizioni Quasar Table of Contents Paola Buzi The Places of Coptic Literary Manuscripts: Real and Imaginary Landscapes. Theoretical Reflections in Guise of Introduction 7 Part I The Geography of Coptic Literature: Archaeological Contexts, Cultural Landscapes, Literary Texts, and Book Forms Jean-Luc Fournet Temples in Late Antique Egypt: Cultic Heritage between Ideology, Pragmatism, and Artistic Recycling 29 Tito Orlandi Localisation and Construction of Churches in Coptic Literature 51 Francesco Valerio Scribes and Scripts in the Library of the Monastery of the Archangel Michael at Phantoou. -

The Tribute Trade with Khotan in Light of Materials Found at the Dunhuang Library Cave

The Tribute Trade with Khotan in Light of Materials Found at the Dunhuang Library Cave V ALERIE HANSEN yale university, new haven Historians have long been interested in the Chi- one jade tablet and one box.”3 This is but one of nese tributary system because of its importance a dozen instances on which Khotanese envoys to understanding China’s relations with other brought tribute to the Chinese between 938 and countries—both in the past and today. Many of 1009.4 In each case, the Chinese sources record today’s intractable foreign policy issues had their the date, the name of the country presenting trib- roots in the tribute system. One has only to think ute, the item presented, and occasionally the of Tibet—was it a part of China during the Qing name of the emissary heading the delegation. dynasty? independent? something in between?— None of these sources, though, records how the to grasp the importance of the topic. participants viewed these exchanges. Nor do we Most studies of the tribute system have focused learn what they received in return for their gifts. on periods like the Qing dynasty (1644–1911) For this information, we must look to the Chi- when China was united and its weaker neigh- nese- and Khotanese-language documents pre- bors presented gifts to the emperor in the capital. served in the library cave of Dunhuang (cave 17 Northwest China in the ninth and tenth centu- according to the numbering in use today) and ries offers a promising comparison because the taken to the United Kingdom, France, and Russia Tang central government, ravaged by the costs of in the early years of the twentieth century. -

Creating Standards

Creating Standards Unauthenticated Download Date | 6/17/19 6:48 PM Studies in Manuscript Cultures Edited by Michael Friedrich Harunaga Isaacson Jörg B. Quenzer Volume 16 Unauthenticated Download Date | 6/17/19 6:48 PM Creating Standards Interactions with Arabic Script in 12 Manuscript Cultures Edited by Dmitry Bondarev Alessandro Gori Lameen Souag Unauthenticated Download Date | 6/17/19 6:48 PM ISBN 978-3-11-063498-3 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-063906-3 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-063508-9 ISSN 2365-9696 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number: 2019935659 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2019 Dmitry Bondarev, Alessandro Gori, Lameen Souag, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com Unauthenticated Download Date | 6/17/19 6:48 PM Contents The Editors Preface VII Transliteration of Arabic and some Arabic-based Script Graphemes used in this Volume (including Persian and Malay) IX Dmitry Bondarev Introduction: Orthographic Polyphony in Arabic Script 1 Paola Orsatti Persian Language in Arabic Script: The Formation of the Orthographic Standard and the Different Graphic Traditions of Iran in the First Centuries of -

RESEARCH on CLOTHING of ANCIENT CHARACTERS in MURALS of DUNHUANG MOGAO GROTTOES and ARTWORKS of SUTRA CAVE LOST OVERSEAS Xia

Global Journal of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences Vol.8, No. 1, pp.41-53, January 2020 Published by ECRTD-UK ISSN: 2052-6350(Print), ISSN: 2052-6369(Online) RESEARCH ON CLOTHING OF ANCIENT CHARACTERS IN MURALS OF DUNHUANG MOGAO GROTTOES AND ARTWORKS OF SUTRA CAVE LOST OVERSEAS Xia Sheng Ping Tunhuangology Information Center of Dunhuang Research Academy, Dunhuang, Gansu Province, China E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT: At the beginning of the twentieth century (1900), the Sutra Cave of the Mogao Grottoes in Dunhuang (presently numbered Cave 17) was discovered by accident. This cave contained tens of thousands of scriptures, artworks, and silk paintings, and became one of the four major archeological discoveries of modern China. The discovery of these texts, artworks, and silk paintings in Dunhuang shook across China and around the world. After the discovery of Dunhuang’s Sutra Cave, expeditions from all over the world flocked to Dunhuang to acquire tens of thousands of ancient manuscripts, silk paintings, embroidery, and other artworks that had been preserved in the Sutra Cave, as well as artifacts from other caves such as murals, clay sculptures, and woodcarvings, causing a significant volume of Dunhuang’s cultural relics to become lost overseas. The emergent field of Tunhuangology, the study of Dunhuang artifacts, has been entirely based on the century-old discovery of the Sutra Cave in Dunhuang’s Mogao Grottoes and the texts and murals unearthed there. However, the dress and clothing of the figures in these lost artworks and cultural relics has not attracted sufficient attention from academic experts. -

The Historical Importance of the Chinese Fragments from Dunhuang in the British Library

THE HISTORICAL IMPORTANCE OF THE CHINESE FRAGMENTS FROM DUNHUANG IN THE BRITISH LIBRARY RONG XINJIANG THE Dunhuang materials obtained by Sir Aurel Stein during his second and third expeditions were divided between the British Museum, the India Office and the Indian government (this final section now being in the National Museum, New Delhi). However, most of the written material remained in Britain. When the British Library separated from the British Museum in 1973 the paintings were retained by the Museum but written materials in Chinese and other languages were deposited in the Oriental Department of the British Library. In the first part of this century, Dr Lionel Giles, Keeper of Oriental Printed Books and Manuscripts at the British Museum, catalogued the Chinese and some bilingual manuscripts, and printed Chinese documents. His Descriptive Catalogue of the Chinese Manuscripts from Tun-huang in the British Museum was published in 1957.^ It covered Stein manuscript numbers Or. 8210/S.1-^980, and printed documents. Or. 8210/P.1-19, from the second and third expeditions. The Chinese Academy of Science obtained microfilm copies of these manuscripts and Liu Mingshu also completed a catalogue of S.1-6980, which was published in 1962.^ Until recently, only this group of manuscripts had been fully studied. However, the manuscripts numbered S. 1-6980 do not cover the whole of the Stein Dunhuang collection. There are many fragmentary manuscripts which Giles omitted from his catalogue. Dr Huang Yungwu of Taiwan compiled a brief catalogue of fragments numbered S.6981-7599 based on a microfilm obtained from Japan,^ and Japanese scholars also carried out detailed research on some of the fragments.^ When I visited the British Library in May 1985, I was told that the manuscript pressmarks had reached S.i 1604.' Funded by a British Academy K. -

Was the Religious Manichaean Narrative a Mythical Narrative? Some Remarks from the Perspective of Andrzej Wierciński's Defini

Studia Religiologica 49 (2) 2016, s. 119–131 doi:10.4467/20844077SR.16.008.5229 www.ejournals.eu/Studia-Religiologica Was the Religious Manichaean Narrative a Mythical Narrative? Some Remarks from the Perspective of Andrzej Wierciński’s Definition of Myth Mariusz Dobkowski Abstract Many specialists in Manichaeism wrote after World War II about the religious Manichaean narra- tive as a myth or a mythology. In this paper I examine whether the Manichaean narrative actually meets the criteria of definition of myth. This question is also worth asking because some scholars emphasise the monosemic character of the mentioned narrative. The definition of myth which I use is that of Andrzej Wierciński (1930–2003), a Polish anthropologist of religion. Among my reasons for choosing this is because it includes as many as nine features of myth and also refers to scien- tific narrative, which by its nature has one level of meaning. I refer this definition, above all, to Manichaean evidence in the Coptic language, but when the need arises I also invoke other sources, both polemical and apologetic. Key words: Manichaeism, myth, Andrzej Wierciński The main reason why I decided to address this issue is the observation that since the mid-twentieth century almost all scholars specialising in Manichaeism have univer- sally talked about the doctrine of “the religion of Light” as a myth or a mythology. For example, in 1949 Henri-Charles Puech wrote these words about the doctrine of Manichaeism in his monograph on this religion: “en fait, malgré toutes ses ambi- tions, dans Manichéisme comme dans tout gnosticisme, cette science qui se croit pure Raison se résout en mythes”.1 Then, in 1998 Manfred Hauser titled his extensive es- say, which reconstructs religious Manichaean narrative on the basis of the discovery from Medinet Madi, “The Manichaean Myth According to The Coptic Sources”.2 And finally, in the most recent monograph on “the religion of Light”, by Nicholas 1 H.-C.