Nuclear Lattice Model and the Electronic Configuration Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Periodic Table

THE PERIODIC TABLE Dr Marius K Mutorwa [email protected] COURSE CONTENT 1. History of the atom 2. Sub-atomic Particles protons, electrons and neutrons 3. Atomic number and Mass number 4. Isotopes and Ions 5. Periodic Table Groups and Periods 6. Properties of metals and non-metals 7. Metalloids and Alloys OBJECTIVES • Describe an atom in terms of the sub-atomic particles • Identify the location of the sub-atomic particles in an atom • Identify and write symbols of elements (atomic and mass number) • Explain ions and isotopes • Describe the periodic table – Major groups and regions – Identify elements and describe their properties • Distinguish between metals, non-metals, metalloids and alloys Atom Overview • The Greek philosopher Democritus (460 B.C. – 370 B.C.) was among the first to suggest the existence of atoms (from the Greek word “atomos”) – He believed that atoms were indivisible and indestructible – His ideas did agree with later scientific theory, but did not explain chemical behavior, and was not based on the scientific method – but just philosophy John Dalton(1766-1844) In 1803, he proposed : 1. All matter is composed of atoms. 2. Atoms cannot be created or destroyed. 3. All the atoms of an element are identical. 4. The atoms of different elements are different. 5. When chemical reactions take place, atoms of different elements join together to form compounds. J.J.Thomson (1856-1940) 1. Proposed the first model of the atom. 2. 1897- Thomson discovered the electron (negatively- charged) – cathode rays 3. Thomson suggested that an atom is a positively- charged sphere with electrons embedded in it. -

The Development of the Periodic Table and Its Consequences Citation: J

Firenze University Press www.fupress.com/substantia The Development of the Periodic Table and its Consequences Citation: J. Emsley (2019) The Devel- opment of the Periodic Table and its Consequences. Substantia 3(2) Suppl. 5: 15-27. doi: 10.13128/Substantia-297 John Emsley Copyright: © 2019 J. Emsley. This is Alameda Lodge, 23a Alameda Road, Ampthill, MK45 2LA, UK an open access, peer-reviewed article E-mail: [email protected] published by Firenze University Press (http://www.fupress.com/substantia) and distributed under the terms of the Abstract. Chemistry is fortunate among the sciences in having an icon that is instant- Creative Commons Attribution License, ly recognisable around the world: the periodic table. The United Nations has deemed which permits unrestricted use, distri- 2019 to be the International Year of the Periodic Table, in commemoration of the 150th bution, and reproduction in any medi- anniversary of the first paper in which it appeared. That had been written by a Russian um, provided the original author and chemist, Dmitri Mendeleev, and was published in May 1869. Since then, there have source are credited. been many versions of the table, but one format has come to be the most widely used Data Availability Statement: All rel- and is to be seen everywhere. The route to this preferred form of the table makes an evant data are within the paper and its interesting story. Supporting Information files. Keywords. Periodic table, Mendeleev, Newlands, Deming, Seaborg. Competing Interests: The Author(s) declare(s) no conflict of interest. INTRODUCTION There are hundreds of periodic tables but the one that is widely repro- duced has the approval of the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) and is shown in Fig.1. -

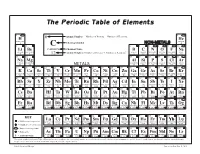

The Periodic Table of Elements

The Periodic Table of Elements 1 2 6 Atomic Number = Number of Protons = Number of Electrons HYDROGENH HELIUMHe 1 Chemical Symbol NON-METALS 4 3 4 C 5 6 7 8 9 10 Li Be CARBON Chemical Name B C N O F Ne LITHIUM BERYLLIUM = Number of Protons + Number of Neutrons* BORON CARBON NITROGEN OXYGEN FLUORINE NEON 7 9 12 Atomic Weight 11 12 14 16 19 20 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 SODIUMNa MAGNESIUMMg ALUMINUMAl SILICONSi PHOSPHORUSP SULFURS CHLORINECl ARGONAr 23 24 METALS 27 28 31 32 35 40 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 POTASSIUMK CALCIUMCa SCANDIUMSc TITANIUMTi VANADIUMV CHROMIUMCr MANGANESEMn FeIRON COBALTCo NICKELNi CuCOPPER ZnZINC GALLIUMGa GERMANIUMGe ARSENICAs SELENIUMSe BROMINEBr KRYPTONKr 39 40 45 48 51 52 55 56 59 59 64 65 70 73 75 79 80 84 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 RUBIDIUMRb STRONTIUMSr YTTRIUMY ZIRCONIUMZr NIOBIUMNb MOLYBDENUMMo TECHNETIUMTc RUTHENIUMRu RHODIUMRh PALLADIUMPd AgSILVER CADMIUMCd INDIUMIn SnTIN ANTIMONYSb TELLURIUMTe IODINEI XeXENON 85 88 89 91 93 96 98 101 103 106 108 112 115 119 122 128 127 131 55 56 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 CESIUMCs BARIUMBa HAFNIUMHf TANTALUMTa TUNGSTENW RHENIUMRe OSMIUMOs IRIDIUMIr PLATINUMPt AuGOLD MERCURYHg THALLIUMTl PbLEAD BISMUTHBi POLONIUMPo ASTATINEAt RnRADON 133 137 178 181 184 186 190 192 195 197 201 204 207 209 209 210 222 87 88 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 FRANCIUMFr RADIUMRa RUTHERFORDIUMRf DUBNIUMDb SEABORGIUMSg BOHRIUMBh HASSIUMHs MEITNERIUMMt DARMSTADTIUMDs ROENTGENIUMRg COPERNICIUMCn NIHONIUMNh -

TEK 8.5C: Periodic Table

Name: Teacher: Pd. Date: TEK 8.5C: Periodic Table TEK 8.5C: Interpret the arrangement of the Periodic Table, including groups and periods, to explain how properties are used to classify elements. Elements and the Periodic Table An element is a substance that cannot be separated into simpler substances by physical or chemical means. An element is already in its simplest form. The smallest piece of an element that still has the properties of that element is called an atom. An element is a pure substance, containing only one kind of atom. The Periodic Table of Elements is a list of all the elements that have been discovered and named, with each element listed in its own element square. Elements are represented on the Periodic Table by a one or two letter symbol, and its name, atomic number and atomic mass. The Periodic Table & Atomic Structure The elements are listed on the Periodic Table in atomic number order, starting at the upper left corner and then moving from the left to right and top to bottom, just as the words of a paragraph are read. The element’s atomic number is based on the number of protons in each atom of that element. In electrically neutral atoms, the atomic number also represents the number of electrons in each atom of that element. For example, the atomic number for neon (Ne) is 10, which means that each atom of neon has 10 protons and 10 electrons. Magnesium (Mg) has an atomic number of 12, which means it has 12 protons and 12 electrons. -

The Quantum Mechanical Model of the Atom

The Quantum Mechanical Model of the Atom Quantum Numbers In order to describe the probable location of electrons, they are assigned four numbers called quantum numbers. The quantum numbers of an electron are kind of like the electron’s “address”. No two electrons can be described by the exact same four quantum numbers. This is called The Pauli Exclusion Principle. • Principle quantum number: The principle quantum number describes which orbit the electron is in and therefore how much energy the electron has. - it is symbolized by the letter n. - positive whole numbers are assigned (not including 0): n=1, n=2, n=3 , etc - the higher the number, the further the orbit from the nucleus - the higher the number, the more energy the electron has (this is sort of like Bohr’s energy levels) - the orbits (energy levels) are also called shells • Angular momentum (azimuthal) quantum number: The azimuthal quantum number describes the sublevels (subshells) that occur in each of the levels (shells) described above. - it is symbolized by the letter l - positive whole number values including 0 are assigned: l = 0, l = 1, l = 2, etc. - each number represents the shape of a subshell: l = 0, represents an s subshell l = 1, represents a p subshell l = 2, represents a d subshell l = 3, represents an f subshell - the higher the number, the more complex the shape of the subshell. The picture below shows the shape of the s and p subshells: (notice the electron clouds) • Magnetic quantum number: All of the subshells described above (except s) have more than one orientation. -

Of the Periodic Table

of the Periodic Table teacher notes Give your students a visual introduction to the families of the periodic table! This product includes eight mini- posters, one for each of the element families on the main group of the periodic table: Alkali Metals, Alkaline Earth Metals, Boron/Aluminum Group (Icosagens), Carbon Group (Crystallogens), Nitrogen Group (Pnictogens), Oxygen Group (Chalcogens), Halogens, and Noble Gases. The mini-posters give overview information about the family as well as a visual of where on the periodic table the family is located and a diagram of an atom of that family highlighting the number of valence electrons. Also included is the student packet, which is broken into the eight families and asks for specific information that students will find on the mini-posters. The students are also directed to color each family with a specific color on the blank graphic organizer at the end of their packet and they go to the fantastic interactive table at www.periodictable.com to learn even more about the elements in each family. Furthermore, there is a section for students to conduct their own research on the element of hydrogen, which does not belong to a family. When I use this activity, I print two of each mini-poster in color (pages 8 through 15 of this file), laminate them, and lay them on a big table. I have students work in partners to read about each family, one at a time, and complete that section of the student packet (pages 16 through 21 of this file). When they finish, they bring the mini-poster back to the table for another group to use. -

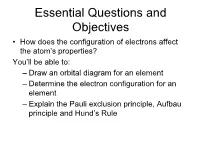

Essential Questions and Objectives

Essential Questions and Objectives • How does the configuration of electrons affect the atom’s properties? You’ll be able to: – Draw an orbital diagram for an element – Determine the electron configuration for an element – Explain the Pauli exclusion principle, Aufbau principle and Hund’s Rule Warm up Set your goals and curiosities for the unit on your tracker. Have your comparison table out for a stamp Bohr v QMM What are some features of the quantum mechanical model of the atom that are not included in the Bohr model? Quantum Mechanical Model • Electrons do not travel around the nucleus of an atom in orbits • They are found in energy levels at different distances away from the nucleus in orbitals • Orbital – region in space where there is a high probability of finding an electron. Atomic Orbitals Electrons cannot exist between energy levels (just like the rungs of a ladder). Principal quantum number (n) indicates the relative size and energy of atomic orbitals. n specifies the atom’s major energy levels also called the principal energy levels. Energy sublevels are contained within the principal energy levels. Ground-State Electron Configuration The arrangement of electrons in the atom is called the electron configuration. Shows where the electrons are - which principal energy levels, which sublevels - and how many electrons in each available space Orbital Filling • The order that electrons fill up orbitals does not follow the order of all n=1’s, then all n=2’s, then all n=3’s, etc. Electron configuration for... Oxygen How many electrons? There are rules to follow to know where they go .. -

Elements Make up the Periodic Table

Page 1 of 7 KEY CONCEPT Elements make up the periodic table. BEFORE, you learned NOW, you will learn • Atoms have a structure • How the periodic table is • Every element is made from organized a different type of atom • How properties of elements are shown by the periodic table VOCABULARY EXPLORE Similarities and Differences of Objects atomic mass p. 17 How can different objects be organized? periodic table p. 18 group p. 22 PROCEDURE MATERIALS period p. 22 buttons 1 With several classmates, organize the buttons into three or more groups. 2 Compare your team’s organization of the buttons with another team’s organization. WHAT DO YOU THINK? • What characteristics did you use to organize the buttons? • In what other ways could you have organized the buttons? Elements can be organized by similarities. One way of organizing elements is by the masses of their atoms. Finding the masses of atoms was a difficult task for the chemists of the past. They could not place an atom on a pan balance. All they could do was find the mass of a very large number of atoms of a certain element and then infer the mass of a single one of them. Remember that not all the atoms of an element have the same atomic mass number. Elements have isotopes. When chemists attempt to measure the mass of an atom, therefore, they are actually finding the average mass of all its isotopes. The atomic mass of the atoms of an element is the average mass of all the element’s isotopes. -

Periodic Table 1 Periodic Table

Periodic table 1 Periodic table This article is about the table used in chemistry. For other uses, see Periodic table (disambiguation). The periodic table is a tabular arrangement of the chemical elements, organized on the basis of their atomic numbers (numbers of protons in the nucleus), electron configurations , and recurring chemical properties. Elements are presented in order of increasing atomic number, which is typically listed with the chemical symbol in each box. The standard form of the table consists of a grid of elements laid out in 18 columns and 7 Standard 18-column form of the periodic table. For the color legend, see section Layout, rows, with a double row of elements under the larger table. below that. The table can also be deconstructed into four rectangular blocks: the s-block to the left, the p-block to the right, the d-block in the middle, and the f-block below that. The rows of the table are called periods; the columns are called groups, with some of these having names such as halogens or noble gases. Since, by definition, a periodic table incorporates recurring trends, any such table can be used to derive relationships between the properties of the elements and predict the properties of new, yet to be discovered or synthesized, elements. As a result, a periodic table—whether in the standard form or some other variant—provides a useful framework for analyzing chemical behavior, and such tables are widely used in chemistry and other sciences. Although precursors exist, Dmitri Mendeleev is generally credited with the publication, in 1869, of the first widely recognized periodic table. -

Unit 3 Electrons and the Periodic Table

UNIT 3 ELECTRONS AND THE PERIODIC TABLE Chapter 5 & 6 CHAPTER 5: ELECTRONS IN ATOMS WHAT ARE THE CHEMICAL PROPERTIES OF ATOMS AND MOLECULES RELATED TO? • ELECTRONS! • Number of valence electrons • How much an atom wants to “gain” or “lose” electrons • How many electrons “gained” or “lost” ELECTRON HISTORY • Dalton’s Model • Didn’t even know of electrons or charge – just ratios of atoms. • Thomson’s Model • ELECTRONS EXIST!!!! • Where are they? No clue. • Plum Pudding? • Rutherford’s Model • Gold Foil Experiment • Electrons are found outside the nucleus. • Now knows where they are, but still doesn’t know how they are organized. Rutherford’s model BOHR’S MODEL • Electron’s are found in energy levels. Quantum: Specific energy values that have exact values in between them. • Pictured the atom like a solar system with electrons “orbiting” around the nucleus. • Each orbit path associated with a particular energy. • Now a better understanding of how electrons are organized, but it still isn’t quite correct. QUANTUM MECHANICAL MODEL ERWIN SCHRODINER (1926) • Electrons are found in regions of empty space around the nucleus. “electron clouds”. • Shape of the region corresponds to different energy levels. • Shape of the region represents the probability of the electron’s location 90% of the time. • PROBLEM? These are still called “atomic orbitals”. SCHRODINGER’S MODEL • Electrons are “wave functions”. • We can’t actually know exactly where an electron is at any moment. • We can know a probability of an electrons location based on its energy. • Ex: a windmill blade ATOMIC ORBITALS • Shape describing the probability of finding an electron at various locations around the nucleus. -

HHE Report No. HETA-2001-0081-2877, Glass

ThisThis Heal Healthth Ha Hazzardard E Evvaluaaluationtion ( H(HHHEE) )report report and and any any r ereccoommmmendendaatitonsions m madeade herein herein are are f orfor t hethe s sppeeccifiicfic f afacciliilityty e evvaluaaluatedted and and may may not not b bee un univeriverssaallllyy appappliliccabable.le. A Anyny re reccoommmmendaendatitoionnss m madeade are are n noot tt oto be be c consonsideredidered as as f ifnalinal s statatetemmeenntsts of of N NIOIOSSHH po polilcicyy or or of of any any agen agenccyy or or i ndindivivididuualal i nvoinvolvlved.ed. AdditionalAdditional HHE HHE repor reportsts are are ava availilabablele at at h htttptp:/://ww/wwww.c.cddcc.gov.gov/n/nioiosshh/hhe/hhe/repor/reportsts ThisThis HealHealtthh HaHazzardard EEvvaluaaluattionion ((HHHHEE)) reportreport andand anyany rreeccoommmmendendaattiionsons mmadeade hereinherein areare fforor tthehe ssppeecciifficic ffaacciliilittyy eevvaluaaluatteded andand maymay notnot bbee ununiiververssaallllyy appappapplililicccababablle.e.le. A AAnynyny re rerecccooommmmmmendaendaendattitiooionnnsss m mmadeadeade are areare n nnooott t t totoo be bebe c cconsonsonsiideredderedidered as asas f fifinalnalinal s ssttataatteteemmmeeennnttstss of ofof N NNIIOIOOSSSHHH po popolliilccicyyy or oror of ofof any anyany agen agenagencccyyy or oror i indndindiivviviiddiduuualalal i invonvoinvollvvlved.ed.ed. AdditionalAdditional HHEHHE reporreporttss areare avaavaililabablele atat hhtttpp::///wwwwww..ccddcc..govgov//nnioiosshh//hhehhe//reporreporttss This Health Hazard Evaluation -

Vapour-Liquid Equilibria of the Neon-Helium System, Cryogenics, 7, 177 (1967) Easitrain – European Advanced Superconductivity Innovation and Training

Fluid properties modeling Jakub Tkaczuk 1,*, Eric Lemmon 2, Ian Bell 2, Francois Millet 1, Nicolas Luchier 1 1 Université Grenoble Alpes, CEA IRIG-dSBT, F-38000 Grenoble, France 2 National Institute of Standards and Technology, Boulder, Colorado 80305, United States * [email protected] Abstract Phase envelope Based upon the conceptual design reports for the FCC cryogenic With the available data points, a shape of the vapor-liquid equilibrium system, the need for more accurate thermodynamic property models of and the occurrence of liquid-liquid equilibrium can be defined (most mixtures was identified. Both academic institutes and world-wide probably no LLE for helium-neon). industries have identified the lack of reliable equation of state for mixtures used at very low temperatures. Detailed cryogenic architecture modeling and design cannot be assessed without valid fluid properties. Therefore, the latter is the focus of this work. Initially driven by the FCC study, the modeling was extended to other fluids beneficial for scientific and industrial application beyond the FCC needs. The properties are modeled for the mixtures of some noble gases with the use of multi-fluid Helmholtz-energy-explicit models: helium-neon, neon-argon, and helium-argon. The on-going studies are performed at CEA-Grenoble, France and at the National Institute of Standards and Technology, U.S. Helmholtz energy equation of state The Helmholtz free energy 훼(훿, 휏) is a thermodynamic potential, which measures useful work obtainable from a closed system. Defining the equation of state (EoS) as a Helmholtz energy-explicit function can be particularly advantageous. Fig. 2.