V56# Nrspring02-Part1live

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ellies 2018 Finalists Announced

Ellies 2018 Finalists Announced New York, The New Yorker top list of National Magazine Award nominees; CNN’s Don Lemon to host annual awards lunch on March 13 NEW YORK, NY (February 1, 2018)—The American Society of Magazine Editors today published the list of finalists for the 2018 National Magazine Awards for Print and Digital Media. For the fifth year, the finalists were first announced in a 90-minute Twittercast. ASME will celebrate the 53rd presentation of the Ellies when each of the 104 finalists is honored at the annual awards lunch. The 2018 winners will be announced during a lunchtime presentation on Tuesday, March 13, at Cipriani Wall Street in New York. The lunch will be hosted by Don Lemon, the anchor of “CNN Tonight With Don Lemon,” airing weeknights at 10. More than 500 magazine editors and publishers are expected to attend. The winners receive “Ellies,” the elephant-shaped statuettes that give the awards their name. The awards lunch will include the presentation of the Magazine Editors’ Hall of Fame Award to the founding editor of Metropolitan Home and Saveur, Dorothy Kalins. Danny Meyer, the chief executive officer of the Union Square Hospitality Group and founder of Shake Shack, will present the Hall of Fame Award to Kalins on behalf of ASME. The 2018 ASME Award for Fiction will also be presented to Michael Ray, the editor of Zoetrope: All-Story. The winners of the 2018 ASME Next Awards for Journalists Under 30 will be honored as well. This year 57 media organizations were nominated in 20 categories, including two new categories, Social Media and Digital Innovation. -

Reporter Privilege: a Con Job Or an Essential Element of Democracy Maguire Center for Ethics and Public Responsibility Public Scholar Presentation November 14, 2007

Reporter Privilege: A Con Job or an Essential Element of Democracy Maguire Center for Ethics and Public Responsibility Public Scholar Presentation November 14, 2007 Two widely divergent cases in recent months have given the public some idea as to what exactly reporter privilege is and whether it may or may not be important in guaranteeing the free flow of information in society. Whether it’s important or not depends on point of view, and, sometimes, one’s political perspective. The case of San Francisco Giants baseball star Barry Bonds and the ongoing issues with steroid use fueled one case in which two San Francisco Chronicle reporters were held in contempt and sentenced to 18 months in jail for refusing to reveal the source of leaked grand jury testimony. According to the testimony, Bonds was among several star athletes who admitted using steroids in the past, although he claimed he did not know at the time the substance he was taking contained steroids. In the other, New York Times reporter Judith Miller served 85 days in jail over her refusal to disclose the source of information that identified a CIA employee, Valerie Plame. The case was complicated with political overtones dealing with the Bush Administration’s claims in early 2003 that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction. A number of other reporter privilege cases were ongoing during the same time period as these two, but the newsworthiness and the subject matter elevated these two cases in terms of extensive news coverage.1 Particularly in the case of Miller, a high-profile reporter for what arguably is the most important news organization in the world, being jailed created a continuing story that was closely followed by journalists and the public. -

Faculty Distinction

Two Thousand Fourteen acult istinction F y D Celebrating the awards, honors and recognition of the Faculty of Arts & Sciences ntroduction I he Faculty of the Arts and Sciences at Columbia University comprises a remarkable array of professors who have been recognized with some of the Tworld’s most prestigious scholarly awards and honors. Over the course of the last academic year, four faculty members were elected to the National Academy of Sciences and three were elected fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Our faculty also received nine honorary degrees, five Guggenheim fellowships, and one Tony Award nomination, in addition to a whole host of other awards and honors. In short, our faculty is exceptional. Standing at the forefront of our distinguished faculty is a commitment to teaching that bears the rigorous and disciplined hallmark of our university. At Columbia, we champion undergraduate, graduate and professional education and celebrate the professors who continue to advance this rich tradition. Through the excellence of our faculty, a Columbia education prepares our students for fulfilling and successful careers that leave a positive mark on the world. Carlos J. Alonso David B. Madigan James J. Valentini Dean of the Graduate Executive Vice President Dean of Columbia College School of Arts & Sciences for Arts & Sciences Vice President for Dean of the Faculty Vice President for Graduate Education of Arts & Sciences Undergraduate Education Morris A. and Alma Schapiro Professor of Statistics Henry L. and Lucy G. Professor in the Humanities Moses Professor umanities umanities H H Rachel Adams Professor of English and Comparative Literature Delta Kappa Gamma Educators Award Schoff Publication Award from the University Seminars program Allison Busch Associate Professor of Middle Eastern, South Asian and African Studies Collaborative Research Award, American Council of Learned Societies (ACLS) Antoine Compagnon Blanche W. -

TATTLER MASTER MAY 2005 Copy

Volume XXXI • Number 18 • May 5, 2005 Midcontinent’s sale of Sioux Falls’ five station cluster to Backyard Broadcasting has resulted in major personnel exits. The list of THE former employees is a long one with GM Mike Costanzo, Talk KELO- AM morning duo Chad McKenzie and Holly Hunter along with MAIN STREET middayer Dave Holly, AC KELO-FM hosts Dave Roberts and Jim Communicator Network Erickson, Country KTWB dude Doc Walker, and Rock KRRO Dave Elliot all getting the axe. This flies in the face of original statements made on the announcement of the sale, when it was said that the TT AA TT TT LL EE RR staff would remain intact. Publisher: Tom Kay Howard Waltman looks to be getting a Senatorial endorsement for Associate Publisher/Editor • Claire Sather his FCC bid from Kansas Republican Sam Brownback. Waltman “Happy Seis de Mayo!” formerly worked as a staffer for the Senator, assisting in certain telecom legislation, later becoming the Chief Telecommunications 30TH LEARNING CONFERENCE GETS Counsel for the House Energy and Commerce Committee in FRANKEN-SENSE! He’s good, smart 2002. It was in that capacity that Waltman had a hand in drafting a enough...and doggone it...people like him! The certain fine-hiking indecency bill. FCC vacancies are being left by Conclave is bringing Air America radio personality the coming exit of Chairman Michael Powell, and possibly exit of and well-known comedian and author, Al Commissioner Kathleen Abernathy. Franken, to deliver one of the featured keynote presentations at the 30th Annual Learning Indianapolis Winter Book. Susquehanna country WFMS takes a Conference on Saturday, July 23, 2005 at the little hit, but remains the market kingpin. -

Communication & Media Studies

COMMUNICATION & MEDIA STUDIES BOOKS FOR COURSES 2011 PENGUIN GROUP (USA) Here is a great selection of Penguin Group (usa)’s Communications & Media Studies titles. Click on the 13-digit ISBN to get more information on each title. n Examination and personal copy forms are available at the back of the catalog. n For personal service, adoption assistance, and complimentary exam copies, sign up for our College Faculty Information Service at www.penguin.com/facinfo 2 COMMUNICaTION & MEDIa STUDIES 2011 CONTENTS Jane McGonigal Mass Communication ................... 3 f REality IS Broken Why Games Make Us Better and Media and Culture .............................4 How They Can Change the World Environment ......................................9 Drawing on positive psychology, cognitive sci- ence, and sociology, Reality Is Broken uncov- Decision-Making ............................... 11 ers how game designers have hit on core truths about what makes us happy and uti- lized these discoveries to astonishing effect in Technology & virtual environments. social media ...................................13 See page 4 Children & Technology ....................15 Journalism ..................................... 16 Food Studies ....................................18 Clay Shirky Government & f CognitivE Surplus Public affairs Reporting ................. 19 Creativity and Generosity Writing for the Media .....................22 in a Connected age Reveals how new technology is changing us from consumers to collaborators, unleashing Radio, TElEvision, a torrent -

Eminem 1 Eminem

Eminem 1 Eminem Eminem Eminem performing live at the DJ Hero Party in Los Angeles, June 1, 2009 Background information Birth name Marshall Bruce Mathers III Born October 17, 1972 Saint Joseph, Missouri, U.S. Origin Warren, Michigan, U.S. Genres Hip hop Occupations Rapper Record producer Actor Songwriter Years active 1995–present Labels Interscope, Aftermath Associated acts Dr. Dre, D12, Royce da 5'9", 50 Cent, Obie Trice Website [www.eminem.com www.eminem.com] Marshall Bruce Mathers III (born October 17, 1972),[1] better known by his stage name Eminem, is an American rapper, record producer, and actor. Eminem quickly gained popularity in 1999 with his major-label debut album, The Slim Shady LP, which won a Grammy Award for Best Rap Album. The following album, The Marshall Mathers LP, became the fastest-selling solo album in United States history.[2] It brought Eminem increased popularity, including his own record label, Shady Records, and brought his group project, D12, to mainstream recognition. The Marshall Mathers LP and his third album, The Eminem Show, also won Grammy Awards, making Eminem the first artist to win Best Rap Album for three consecutive LPs. He then won the award again in 2010 for his album Relapse and in 2011 for his album Recovery, giving him a total of 13 Grammys in his career. In 2003, he won the Academy Award for Best Original Song for "Lose Yourself" from the film, 8 Mile, in which he also played the lead. "Lose Yourself" would go on to become the longest running No. 1 hip hop single.[3] Eminem then went on hiatus after touring in 2005. -

![Download Music for Free.] in Work, Even Though It Gains Access to It](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0418/download-music-for-free-in-work-even-though-it-gains-access-to-it-680418.webp)

Download Music for Free.] in Work, Even Though It Gains Access to It

Vol. 54 No. 3 NIEMAN REPORTS Fall 2000 THE NIEMAN FOUNDATION FOR JOURNALISM AT HARVARD UNIVERSITY 4 Narrative Journalism 5 Narrative Journalism Comes of Age BY MARK KRAMER 9 Exploring Relationships Across Racial Lines BY GERALD BOYD 11 The False Dichotomy and Narrative Journalism BY ROY PETER CLARK 13 The Verdict Is in the 112th Paragraph BY THOMAS FRENCH 16 ‘Just Write What Happened.’ BY WILLIAM F. WOO 18 The State of Narrative Nonfiction Writing ROBERT VARE 20 Talking About Narrative Journalism A PANEL OF JOURNALISTS 23 ‘Narrative Writing Looked Easy.’ BY RICHARD READ 25 Narrative Journalism Goes Multimedia BY MARK BOWDEN 29 Weaving Storytelling Into Breaking News BY RICK BRAGG 31 The Perils of Lunch With Sharon Stone BY ANTHONY DECURTIS 33 Lulling Viewers Into a State of Complicity BY TED KOPPEL 34 Sticky Storytelling BY ROBERT KRULWICH 35 Has the Camera’s Eye Replaced the Writer’s Descriptive Hand? MICHAEL KELLY 37 Narrative Storytelling in a Drive-By Medium BY CAROLYN MUNGO 39 Combining Narrative With Analysis BY LAURA SESSIONS STEPP 42 Literary Nonfiction Constructs a Narrative Foundation BY MADELEINE BLAIS 43 Me and the System: The Personal Essay and Health Policy BY FITZHUGH MULLAN 45 Photojournalism 46 Photographs BY JAMES NACHTWEY 48 The Unbearable Weight of Witness BY MICHELE MCDONALD 49 Photographers Can’t Hide Behind Their Cameras BY STEVE NORTHUP 51 Do Images of War Need Justification? BY PHILIP CAPUTO Cover photo: A Muslim man begs for his life as he is taken prisoner by Arkan’s Tigers during the first battle for Bosnia in March 1992. -

How America Went Haywire

Have Smartphones Why Women Bully Destroyed a Each Other at Work Generation? p. 58 BY OLGA KHAZAN Conspiracy Theories. Fake News. Magical Thinking. How America Went Haywire By Kurt Andersen The Rise of the Violent Left Jane Austen Is Everything The Whitest Music Ever John le Carré Goes SEPTEMBER 2017 Back Into the Cold THEATLANTIC.COM 0917_Cover [Print].indd 1 7/19/2017 1:57:09 PM TerTeTere msm appppply.ly Viistsits ameierier cancaanexpexpresre scs.cs.s com/om busbubusinesspsplatl inuummt to learnmn moreorer . Hogarth &Ogilvy Hogarth 212.237.7000 CODE: FILE: DESCRIPTION: 29A-008875-25C-PBC-17-238F.indd PBC-17-238F TAKE A BREAK BEFORE TAKING ONTHEWORLD ABREAKBEFORETAKING TAKE PUB/POST: The Atlantic -9/17issue(Due TheAtlantic SAP #: #: WORKORDER PRODUCTION: AP.AP PBC.17020.K.011 AP.AP al_stacked_l_18in_wide_cmyk.psd Art: D.Hanson AP17006A_003C_EarlyCheckIn_SWOP3.tif 008875 BLEED: TRIM: LIVE: (CMYK; 3881 ppi; Up toDate) (CMYK; 3881ppi;Up 15.25” x10” 15.75”x10.5” 16”x10.75” (CMYK; 908 ppi; Up toDate), (CMYK; 908ppi;Up 008875-13A-TAKE_A_BREAK_CMYK-TintRev.eps 008875-13A-TAKE_A_BREAK_CMYK-TintRev.eps (Up toDate), (Up AP- American Express-RegMark-4C.ai AP- AmericanExpress-RegMark-4C.ai (Up toDate), (Up sbs_fr_chg_plat_met- at americanexpress.com/exploreplatinum at PlatinumMembership Business of theworld Explore FineHotelsandResorts. hand-picked 975 atover head your andclear early Arrive TerTeTere msm appppply.ly Viistsits ameierier cancaanexpexpresre scs.cs.s com/om busbubusinesspsplatl inuummt to learnmn moreorer . Hogarth &Ogilvy Hogarth 212.237.7000 -

FY19 Annual Report View Report

Annual Report 2018–19 3 Introduction 5 Metropolitan Opera Board of Directors 6 Season Repertory and Events 14 Artist Roster 16 The Financial Results 20 Our Patrons On the cover: Yannick Nézet-Séguin takes a bow after his first official performance as Jeanette Lerman-Neubauer Music Director PHOTO: JONATHAN TICHLER / MET OPERA 2 Introduction The 2018–19 season was a historic one for the Metropolitan Opera. Not only did the company present more than 200 exiting performances, but we also welcomed Yannick Nézet-Séguin as the Met’s new Jeanette Lerman- Neubauer Music Director. Maestro Nézet-Séguin is only the third conductor to hold the title of Music Director since the company’s founding in 1883. I am also happy to report that the 2018–19 season marked the fifth year running in which the company’s finances were balanced or very nearly so, as we recorded a very small deficit of less than 1% of expenses. The season opened with the premiere of a new staging of Saint-Saëns’s epic Samson et Dalila and also included three other new productions, as well as three exhilarating full cycles of Wagner’s Ring and a full slate of 18 revivals. The Live in HD series of cinema transmissions brought opera to audiences around the world for the 13th season, with ten broadcasts reaching more than two million people. Combined earned revenue for the Met (box office, media, and presentations) totaled $121 million. As in past seasons, total paid attendance for the season in the opera house was 75%. The new productions in the 2018–19 season were the work of three distinguished directors, two having had previous successes at the Met and one making his company debut. -

Pilots in the Offshore Oil Industry

CE AND PROFESSIONAL EMPLOYEES INTERNATIONAL UNION, AFL-CIO AND CLC No. 467 -ger--3 Issue 2, 1999 OPEIU reaches agreement covering pilots in the offshore oil industry Historic contract provides 35 percent wage increase The Office and Professional Employ- "This contract is the result of the dedica- OPEIU International Vice President J.B. es will be realized in the first year. The com- ees International Union (OPEIU) has tion of our members who steadfastly held Moss and International Business Rep- pany will also pay substantial signing reached a contract agreement with together during protracted negotiations," said resentative Paul Bohelski teamed up with bonuses, with each pilot receiving $600 per Offshore Logistics, Inc. (OLOG) that will Jim Morgan, a veteran pilot and president of Morgan and the negotiating committee to year of service to OLOG. Additional mean a 35 percent wage increase over the Local 107. "We achieved our goals of fair help realize this contract. increases were negotiated for pilots working life of the contract for the 208 pilots em- pay, improved health insurance, retirement The four-year agreement provides for 35 premium shifts. ployed by the company. The pilots are security and dignity and respect on the job. percent wage increases over the life of the Pilots will also see significant reductions members of OPEIU Local 107. "This contract will greatly improve the contract - up to 24 percent of the increas- Continued on page 3 The agreement is the first contract that lives of pilots throughout the Gulf region covers pilots who provide helicopter service who will go from being the least compen- to the offshore oil industry in the Gulf of sated pilots in the industry to having work- Mexico; it also covers pilots providing ser- ing conditions that are the envy of pilots vice to oil field and other operations in from Mobile to Corpus Christi," Morgan Alaska. -

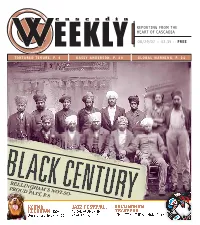

Cascadia BELLINGHAM's NOT-SO

cascadia REPORTING FROM THE HEART OF CASCADIA 08/29/07 :: 02.35 :: FREE TORTURED TENURE, P. 6 KASEY ANDERSON, P. 20 GLOBAL WARNING, P. 24 BELLINGHAM’S NOT-SO- PROUD PAST, P.8 HOUND JAZZ FESTIVAL: BELLINGHAM HOEDOWN: DOG AURAL ACUMEN IN TRAVERSE: DAYS OF SUMMER, P. 16 ANACORTES, P. 21 SIMULATING THE SALMON, P. 17 NURSERY, LANDSCAPING & ORCHARDS Sustainable ] 35 UNIQUE PLANTS Communities ][ FOOD FOR NORTHWEST & land use conference 28-33 GARDENS Thursday, September 6 ornamentals, natives, fruit ][ CLASSIFIEDS ][ LANDSCAPE & 24-27 DESIGN SERVICES ][ FILM Fall Hours start Sept. 5: Wed-Sat 10-5, Sun 11-4 20-23 Summer: Wed-Sat 10-5 , Goodwin Road, Everson Join Sustainable Connections to learn from key ][ MUSIC ][ www.cloudmountainfarm.com stakeholders from remarkable Cascadia Region 19 development featuring: ][ ART ][ Brownfields Urban waterfronts 18 Modern Furniture Fans in Washington &Canada Urban villages Urban growth areas (we deliver direct to you!) LIVE MUSIC Rural development Farmland preservation ][ ON STAGE ][ Thurs. & Sat. at 8 p.m. In addition, special hands on work sessions will present 17 the opportunity to get updates on, and provide feedback to, local plans and projects. ][ GET ][ OUT details & agenda: www.SustainableConnections.org 16 Queen bed Visit us for ROCK $699 BOTTOM Prices on Home Furnishings ][ WORDS & COMMUNITY WORDS & ][ 8-15 ][ CURRENTS We will From 6-7 CRUSH $699 Anyone’s Prices ][ VIEWS ][ on 4-5 ][ MAIL 3 DO IT IT DO $569 .07 29 A little out of the way… 08. But worth it. 1322 Cornwall Ave. Downtown Bellingham Striving to serve the community of Whatcom, Skagit, Island Counties & British Columbia CASCADIA WEEKLY #2.35 (Between Holly & Magnolia) 733-7900 8038 Guide Meridian (360) 354-1000 www.LeftCoastFurnishings.com Lynden, Washington www.pioneerford.net 2 *we reserve the right not to sell below our cost c . -

Disaster Preparedness, Resilience, and Response Forum Report

Columbia World Projects: Disaster Preparedness, Resilience, and Response Forum Report August 15, 2019 Foreword Dear Reader, On behalf of Columbia World Projects (CWP), we are pleased to present the following report on our Forum on Disaster Preparedness, Resilience, and Response, one of an ongoing series of meetings dedicated to bringing together academia with partners from government, non- governmental and intergovernmental organizations, the media, and the private sector to identify projects designed to tackle fundamental challenges facing humanity. Natural disasters and public health emergencies impact tens of millions of people each year. At the individual level, the impact is often felt physically, mentally, and emotionally, and can destroy homes and businesses, wipe out financial resources, uproot families, and cause lasting injuries and even deaths. At the community and regional level, the impact can be equally devastating, inflicting enormous environmental and structural damage; stalling or even reversing a society’s economic growth and development; and producing and exacerbating poverty and instability. While natural disasters and public health emergencies have been a consistent feature of human existence, the frequency and intensity of such incidents have increased over the last few decades, in significant part as a result of climate change and growing mobility. All of this has made managing disasters more urgent, more expensive, and more complex. On June 10, 2019, CWP invited approximately 35 experts from a range of fields and disciplines to take part in a Forum with the aim not only of deepening our understanding of natural disasters and public health emergencies, but also of proposing concrete ways to improve the lives of people affected by these events.