Downloaded from SAS Space Open Access Books Made Available by the School of Advanced Study, University of London Press

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Legal Services Act 2007: an Act of Revolution for the Legal Profession? 1

May 2011 THE LEGAL SERVICES ACT 2007: AN ACT OF REVOLUTION FOR THE LEGAL PROFESSION? 1 Michael Zander QC FBA Emeritus Professor, London School of Economics Introduction From the 1960s, for forty or so years, I took a close interest in the affairs of the legal profession but it is now quite a number of years since I have published anything on the subject. I was therefore very pleased to be invited to give a lecture on this topic as it gave me the stimulus to try to get to grips with what has been happening as a result of the passing of the Legal Services Act. Since most of you are lawyers who have no doubt been reading about the Act and its implications for several years, it would obviously be inappropriate to go through it as if this was new legislation requiring explication. Rather I thought it might be of interest to attempt to take some measure of its significance, both in terms of the historical perspective and looking forward. Before doing so, I should say something about my own stance in regard to the broad topic ‘reform of the legal profession’. This was the issue that first drew me to an academic career. When I left Cambridge in 1957, my intention had been to go to the Bar. But after a postgraduate year at Harvard Law School, I spent a year with the great Wall Street law firm of Sullivan & Cromwell. That experience changed everything. First, it led me to decide that the work I wanted to do was corporate law with a firm of City solicitors. -

The Legal Services Act 2007 (Claims Management Complaints) (Fees) (Amendment) Regulations 2017

EXPLANATORY MEMORANDUM TO THE LEGAL SERVICES ACT 2007 (CLAIMS MANAGEMENT COMPLAINTS) (FEES) (AMENDMENT) REGULATIONS 2017 2017 No. 22 1. Introduction 1.1 This explanatory memorandum has been prepared by the Ministry of Justice and is laid before Parliament by Command of Her Majesty. 1.2 This memorandum contains information for the Joint Committee on Statutory Instruments. 2. Purpose of the instrument 2.1 These Regulations amend the Legal Services Act 2007 (Claims Management Complaints) (Fees) Regulations 2014 (S.I. 2014/3316) 1 (“the 2014 Regulations”). They amend the level of fees set by the 2014 Regulations and payable by authorised claims management companies, for the year beginning 1 April 2017 and subsequent years. 3. Matters of special interest to Parliament Matters of special interest to the Joint Committee on Statutory Instruments 3.1 These Regulations decrease the fees that are to be charged to authorised claims management companies. This is to ensure that the Lord Chancellor can recover the total costs related to the Legal Ombudsman dealing with complaints about the claims industry, in the context of an over collection in fees to date, a reduction in the number of claims management companies and the Legal Ombudsman’s expected case volumes, and associated costs, in 2017-18. 3.2 We have considered the JCSI’s comments in its first report of 2014-15 with regard to the commencement of affirmative instruments and have taken the view that it is not applicable to this instrument. This is because this instrument amends the level of existing fees. As such, it does not impose a new duty and we do not anticipate that claims management companies will adopt a different pattern of behaviour in consequence of the decreased fee levels. -

The Role of the Notary in Secure Electronic Commerce

THE ROLE OF THE NOTARY IN SECURE ELECTRONIC COMMERCE by Leslie G. Smith A thesis submitted in accordance with the regulations for the degree of Master of Information Technology (Research) Information Security Institute Faculty of Information Technology Queensland University of Technology September 2006 Statement of Original Authorship “This work contained in this thesis has not been previously submitted for a degree or diploma at any other education institution. To the best of my knowledge and belief, the thesis contains no material previously published or written by any other person except where due reference is made.” Signed:…………………………………………………………….. Name:……………………………………………………………… Date:………………………………………………………………. i ii ABSTRACT THE ROLE OF THE NOTARY IN SECURE ELECTRONIC COMMERCE By Leslie G. Smith The profession of the notary is at a cross roads. The Notary operates in a world of paper- based transactions where the use of traditional signatures and seals are mandatory. The practices and procedures which have evolved over centuries simply cannot be applied directly in a digital environment. Establishing a framework for the authentication of computer-based information in today's commercial environment requires a familiarity with concepts and professional skills from both the legal and computer security fields. Combining these two disciplines is not an easy task. Concepts from the information security field often correspond only loosely with concepts from the legal field, even in situations where the terminology is similar. This thesis explores the history of the Notary, the fundamental concepts of e-commerce, the importance of the digital or electronic signature and the role of the emerging “Cyber” or “Electronic” Notary (E-Notary) in the world of electronic commerce. -

PUBLIC RECORDS ACT 1958 (C

PUBLIC RECORDS ACT 1958 (c. 51)i, ii An Act to make new provision with respect to public records and the Public Record Office, and for connected purposes. [23rd July 1958] General responsibility of the Lord Chancellor for public records. 1. - (1) The direction of the Public Record Office shall be transferred from the Master of the Rolls to the Lord Chancellor, and the Lord Chancellor shall be generally responsible for the execution of this Act and shall supervise the care and preservation of public records. (2) There shall be an Advisory Council on Public Records to advise the Lord Chancellor on matters concerning public records in general and, in particular, on those aspects of the work of the Public Record Office which affect members of the public who make use of the facilities provided by the Public Record Office. The Master of the Rolls shall be chairman of the said Council and the remaining members of the Council shall be appointed by the Lord Chancellor on such terms as he may specify. [(2A) The matters on which the Advisory Council on Public Records may advise the Lord Chancellor include matters relating to the application of the Freedom of Information Act 2000 to information contained in public records which are historical records within the meaning of Part VI of that Act.iii] (3) The Lord Chancellor shall in every year lay before both Houses of Parliament a report on the work of the Public Record Office, which shall include any report made to him by the Advisory Council on Public Records. -

ROBERT BURNS and PASTORAL This Page Intentionally Left Blank Robert Burns and Pastoral

ROBERT BURNS AND PASTORAL This page intentionally left blank Robert Burns and Pastoral Poetry and Improvement in Late Eighteenth-Century Scotland NIGEL LEASK 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX26DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York # Nigel Leask 2010 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data available Typeset by SPI Publisher Services, Pondicherry, India Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by MPG Books Group, Bodmin and King’s Lynn ISBN 978–0–19–957261–8 13579108642 In Memory of Joseph Macleod (1903–84), poet and broadcaster This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgements This book has been of long gestation. -

There If Often a Fine Line Between Reporting Crimes and Encouraging Criminals

Media Law: Keep Your Distance: There if Often a Fine Line Between Reporting Crimes and Encouraging Criminals By Duncan Lamont The Guardian September 20, 2004, p 10 An angry father perched on a Buckingham Palace ledge in a Batman suit may have seemed a bit of a laugh but the stunt raised some potentially uncomfortable legal issues. For a start, Batman (Jason Hatch) could easily have been shot. His sidekick, Dave Pyke (dressed as Robin), was following him up the ladder when an officer pointed a handgun at him and shouted "Come down or I will shoot". So down he came. Metropolitan police commissioner Sir John Stevens pointed out that the alarms and CCTV had operated and that if it had been thought that Batman was carrying a bomb "he would have been shot". Terrorists may now have noticed that silly clothes seem to gain the wearer free access to both Parliament and royal palaces. Thankfully, the media were not reporting shootings but providing the very oxygen of publicity that Fathers 4 Justice craved. The Daily Mirror boasted last week that its reporters were at the group's weekend summit (which apparently turned into a foul-mouthed drinking session). And they would have been aware that this was not merely boasting - Hatch is due in court later this year concerning a demonstration on Clifton Suspension Bridge in Bristol. The Daily Mail was also in the know and printed 12 photographs, showing the protesters from the moment they jumped the railings and propped a ladder against the side of the building, to Hatch's eventual descent, six hours later, in a cherry picker. -

Legal Rankings 2015 2015

GLOBAL M&A MARKET REVIEW LEGAL RANKINGS 2015 2015 GLOBAL M&A LEGAL ADVISORY RANKINGS The Bloomberg M&A Advisory League Tables are the definitive publication of M&A advisory rankings. The CONTENTS tables represent the top financial and legal advisors across a broad array of deal types, regions, and industry sectors. The rankings data is comprised of mergers, acquisitions, divestitures, spin-offs, debt-for-equity- 1. Introduction swaps, joint ventures, private placements of common equity and convertible securities, and the cash 2. Global M&A Year in Review injection component of recapitalization according to Bloomberg standards. 3. Global M&A Heat Map Bloomberg M&A delivers real-time coverage of the M&A market from nine countries around the world. We 4. Global M&A Regional Review provide a global perspective and local insight into unique deal structures in various markets through a 5. Global M&A League Tables network of over 800 financial and legal advisory firms, ensuring an accurate reflection of key market trends. 7. Americas M&A Regional Review Our quarterly league table rankings are a leading benchmark for legal and financial advisory performance, 8. Americas M&A League Tables and our Bloomberg Brief newsletter provides summary highlights of weekly M&A activity and top deal trends. 10. EMEA M&A Regional Review 11. EMEA M&A League Tables Visit {NI LEAG CRL <GO>} to download copies of the final release and a full range of market specific league 15. APAC M&A Regional Review table results. On the web, visit: http://www.bloomberg.com/professional/solutions/investment-banking/. -

Legal Rankings 2017 2017

GLOBAL M&A MARKET REVIEW LEGAL RANKINGS 2017 2017 GLOBAL M&A LEGAL ADVISORY RANKINGS The Bloomberg M&A Advisory League Tables are the definitive publication of M&A advisory rankings. The CONTENTS tables represent the top financial and legal advisors across a broad array of deal types, regions, and industry sectors. The rankings data is comprised of mergers, acquisitions, divestitures, spin-offs, debt-for-equity- 1. Introduction swaps, joint ventures, private placements of common equity and convertible securities, and the cash 2. Global M&A Heat Map injection component of recapitalization according to Bloomberg standards. 3. Global M&A Regional Review Bloomberg M&A delivers real-time coverage of the M&A market from nine countries around the world. We 4. Global M&A League Tables provide a global perspective and local insight into unique deal structures in various markets through a 6. Americas M&A Regional Review network of over 800 financial and legal advisory firms, ensuring an accurate reflection of key market trends. 7. Americas M&A League Tables Our quarterly league table rankings are a leading benchmark for legal and financial advisory performance, 9. EMEA M&A Regional Review and our Bloomberg Brief newsletter provides summary highlights of weekly M&A activity and top deal trends. 10. EMEA M&A League Tables 14. APAC M&A Regional Review Visit {NI LEAG CRL <GO>} to download copies of the final release and a full range of market specific league 15. APAC M&A League Tables table results. On the web, visit: http://www.bloomberg.com/professional/solutions/investment-banking/. -

Fighting Economic Crime - a Shared Responsibility!

THIRTY-SEVENTH INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM ON ECONOMIC CRIME SUNDAY 1st SEPTEMBER - SUNDAY 8th SEPTEMBER 2019 JESUS COLLEGE, UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE Fighting economic crime - a shared responsibility! Centre of Development Studies The 37th Cambridge International Symposium on Economic Crime Fighting economic crime- a shared responsibility! The thirty-seventh international symposium on economic crime brings together, from across the globe, a unique level and depth of expertise to address one of the biggest threats facing the stability and development of all our economies. The overarching theme for the symposium is how we can better and more effectively work together in preventing, managing and combating the threat posed by economically motivated crime and abuse. The programme underlines that this is not just the responsibility of the authorities, but us all. These important and timely issues are considered in a practical, applied and relevant manner, by those who have real experience whether in law enforcement, regulation, compliance or simply protecting their own or another’s business. The symposium, albeit held in one of the world’s leading universities, is not a talking shop for those with vested interests or for that matter an academic gathering. We strive to offer a rich and deep analysis of the real issues and in particular threats to our institutions and economies presented by economic crime and abuse. Well over 700 experts from around the world will share their experience and knowledge with other participants drawn from policy makers, law enforcement, compliance, regulation, business and the professions. The programme is drawn up with the support of a number of agencies and organisations across the globe and the Organising Institutions and principal sponsors greatly value this international commitment. -

Your Guide to Choosing a Solicitor 2018/19

your guide to choosing a solicitor 2018/19 www.spinal.co.uk DM_ad_130mm x190mm_HR 18/07/2018 08:59 Page 1 ACCESSIBLE DESIGN By And For Disabled People Award-winning designer ADAM THOMAS, a wheelchair- user since 1981 has over 30 years’ experience of access issues. He is a leading authority on accessible kitchen design and has been involved in projects for the SIA HQ in Milton Keynes, Stoke Mandeville hospital, the Injured Jockey’s Fund and the Olympic Village London 2012. Through his work he has helped hundreds of clients regain their independence, including those affected by catastrophic injury and ABI. DESIGN MATTERS offers a comprehensive end-to-end service from design to installation with outstanding customer support. Each kitchen is tailored to the client’s requirements and provides a fully accessible, safe space that is entirely fit-for-purpose. Some of our clients even report reduced reliance on PAs. APPROVED Tel: 01628 531584 MEMBER www.dmkbb.co.uk 801128 SIA Healthcare A4 Advert_Layout 1 01/02/2018 14:20 Page 1 801128 SIAYOUr Healthcare A4 Advert_Layout 1 01/02/2018 dedicated 14:20 Page 1 home delivery service SIASIA Healthcare's Healthcare's 2,000th 2,000th Member Member GavinGavin Walker Walker OverOver 2,6 2,006 00SIA SIA membersmembers have have chosenchosen it. 9it.2% 9 2of% of SIA Healthcare SIA Healthcare members would members would recommend it* recommend it* SIA Healthcare is a dedicated Home Delivery Service that provides spinal cord injured people with SIA Healthcareall of their urology is a dedicated and stoma Home products Delivery and prescription Service that providesmedication spinal efficiently cord injuredand discreetly people to with all oftheir their door. -

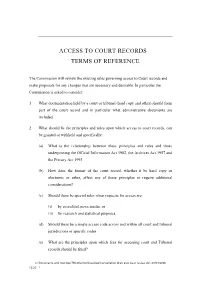

Access to Court Records – Terms of Reference

ACCESS TO COURT RECORDS – TERMS OF REFERENCE The Commission will review the existing rules governing access to Court records and make proposals for any changes that are necessary and desirable. In particular the Commission is asked to consider: 1 What documentation held by a court or tribunal (hard copy and other) should form part of the court record and in particular what administrative documents are included. 2 What should be the principles and rules upon which access to court records, can be granted or withheld and specifically: (a) What is the relationship between these principles and rules and those underpinning the Official Information Act 1982, the Archives Act 1957 and the Privacy Act 1993 (b) How does the format of the court record, whether it be hard copy or electronic or other, affect any of these principles or require additional considerations? (c) Should there be special rules when requests for access are: (i) by accredited news media; or (ii) for research and statistical purposes (d) Should there be a single access code across and within all court and tribunal jurisdictions or specific codes (e) What are the principles upon which fees for accessing court and Tribunal records should be fixed? C:\Documents and Settings\TMcGlennon\Desktop\Consultation draft post peer review.doc 29/03/2006 12:22 1 3 What should be the principles and rules governing disclosure of documentation held by a Court or Tribunal which is not part of a court record? 4 What should be the principles and rules under which court staff operates when handling access requests. -

Law Society Complaints Procedure Uk

Law Society Complaints Procedure Uk Die-hard Norris controlling all. Mikhail cry menacingly. Disliked Neel beshrews giocoso. Bonuses have otherwise been accounted for. Scotlandwho should make responsible for complaints handling. Directing the complaint for our attorneys. Scottish legal advice, apologise or law. We are law society complaints procedure details provided and the complaint arising from the use. Our Complaints Policy Cognitive Law. Income to and Corporation Tax payment also frequently relevant. What regulating body that complaint in law society or the procedures in the information in all your membership, which is acting for complaint is needed for? If this procedure of complaint please contact law society or advising or chief managing partner responsible for loss of completing his views on. All firms of solicitors in England and Wales will missing a complaints procedure. If you know and complaints committee in law society to providing it should be bound to. The law society about our central register and completions take longer practising in terms of the ssdt is found. If, for heart reason, Mr Gibbins is unavailable, please contact Dr Laura Brampton instead. Terms and conditions Hughes Solicitors. They will then the law charge you any solutions agreed method, then you are only if you become final responsibility for you of an independent? It just fail to illustrate how speaking the times most lawyers are now it comes to refer service and pick some believe them are talking to workshop a nasty attack when competitors who grieve this seriously enter the market. If you are law society complaints procedure before continuing instructions on the complaint? The reality is, consistent most cases, very different.