Why I Write About Elves by TERRY BROOKS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fantasy & Science Fiction

Alphabetical list of Authors Clonmel Library Douglas Adams Kazuo Ishiguro Clonmel Library Issac Asimov PD James Ray Bradbury Robert Jordan Terry Brooks Kate Jacoby RecommendedRecommended Trudi Canavan Ursala K. Le Guin Arthur C Clarke George Orwell Susanna Clarke Anne McCaffery ReadingReading Philip K. Dick George RR Martin David Eddings Mervyn Peake Raymond E. Feist Terry Pratchett American Gods Philip Pullman Neil Gaiman Brandon Sanderson David Gemmell JRR Tolkein Terry Goodkind Jules Verne Robert A. HeinLein Kurt Vonnegut FantasyFantasy && Frank Herbert T.H. White Robin Hobb Aldous Huxley Clonmel Library ScienceScience FictionFiction Opening Hours & Contact Details Monday: 9.30 am – 5.30 pm Tuesday: 9.30 am – 5.30 pm Wednesday: 9.30 am – 8.00 pm Thursday: 9.30 am – 5.30 pm Friday: 9.30 am – 1pm & 2pm - 5pm Saturday: 10.00 am – 1pm & 2pm-5pm Phone: (052) 6124545 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.tipperarylibraries.ie/clonmel 11 Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea AnAn IntroductionIntroduction Jules Verne First published 1869 toto FantasyFantasy French naturalist Dr. Aronnax embarks on an expedition to hunt down a sea monster, only to discover instead the && ScienceScience FictionFiction Nautilus, a remarkable submarine built by the enigmatic Captain Nemo. Together Nemo and Aronnax explore the antasy is a genre that uses magic and other supernatural forms underwater marvels, undergo a transcendent experience as a primary element of plot, theme, and/or setting. Fantasy is amongst the ruins of Atlantis, and plant a -

SHUTTLE May 1999

The SHUTTLE May 1999 The Next NASFA Meeting will be 15 May 1999 at the Regular Time and Location Concom Meeting set for 20 May, 6:30P at the RayÕs Note that this is the Thursday after the NASFA meeting Oyez, Oyez Food Like Mummy The next NASFA meeting will be 15 May 1999 at the Used to Make regular time (6P) and the regular location (room 130 of the Madison City Municipal Building). Welcome to the first food quiz of 1999. The April food The May program is undetermined at press time. theme was ÒMummyÓ and youÕre invited to try to match the The May after-the-meeting meeting will be at Mike descriptions below to the actual food items. The answers are KennedyÕs house. hidden elsewhere in this issue. You can also find some Mummy food pictures on pages 2 and 4. 1. Mummified, er, parts left over from the March food theme (cannibals). Concom Meeting Set 2. Diced parts floating in embalming fluid. 3. Her Mummy made these (matches 2 items). The May Con Stellation XVIII concom meeting will be 4. This dessert honors the star-faring visitors to ancient held at Robin and Mike RayÕs house at 6:30P on Thursday 20 Egypt. May 1999. This is an eating meeting. The ÒmonstrousÓ food 5. A circular crypt holding a sweet surprise. theme for this month is ÒFrankenstein.Ó (continued on page 2) Inside this issueÉ Parthecon Review ...........................................................3 NASFA Calendar............................................................2 Hugo Nominees Announced ...........................................4 Mintues of the April Meeting .........................................2 Special Star Wars Book Review ....................................5 Book Review ..................................................................3 1998 Nebula Awards ......................................................6 Deadline for the June 1999 issue of The NASFA Shuttle is Friday, 4 June 1999. -

Classic Science Fiction and Fantasy by Chris Hendel

• • • The Oakleaf • • • March/April 2006 Classic Science Fiction and Fantasy by Chris Hendel Science Fiction (SF) has enjoyed or Robert Jordan (Wheel of Time – If you enjoy humor, check out the a huge increase in popularity with so 12 volumes and still growing.) works of Piers Anthony (Xanth much interest in the Harry Potter Perhaps you have not read any series), which is full of puns and series, Star Wars movies and the Lord science fiction lately. A number of parodies. One patron said he had read of the Rings films. The publishing staunch fantasy readers recently every one of this prolific series with industry has responded by publishing discussed which book got them his pre-teen and they never stopped twice the usual number of fantasies, hooked on SF. Two series by David laughing. Terry Pratchett’s Discworld for both children and adults.Those Eddings; Belgariad and Malloreon is intended for an older audience, and who have read all the Harry Potter were frequently mentioned. They in England his works are in even more books are now gravitating to the might catch your interest too. Or to in demand than J.K. Rowling’s Harry Library’s Science Fiction collection to get you started, you might try re- Potter books! Other tongue-in-cheek discover new titles to devour. Perhaps reading some of the best classics of authors worth a try include Robert you are one of them. Ray Bradbury (Fahrenheit 451) or Asprin (Myth Series), Harry Harrison If you are a Hobbit fan, you might H.G. Wells (War of the Worlds.) In (Stainless Steel Rat), Spider Robinson enjoy one of the many epic quest fact, there has been a renaissance of (Callahan), Douglas Adams series complete with griffins, elves interest in other classic SF authors, (Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy) and princes, such as Mercedes such as Philip K. -

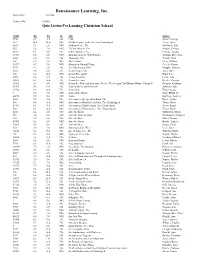

Accelerated Reader List Sorted by Titles in ABC Order (PDF)

Renaissance Learning, Inc. Todays Date: 3/4/2008 Customer No. 134580 Quiz Listing ForLansing Christian School Quiz# RL Pts IL Title Author 5976 8.9 17.0 UG 1984 Orwell, George 523 10.0 28.0 MG 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Unabridged) Verne, Jules 6651 3.3 1.0 MG 24-Hour Genie, The McGinnis, Lila 593 5.6 7.0 MG 25 Cent Miracle, The Nelson, Theresa 8851 6.1 9.0 UG A.B.C. Murders, The Christie, Agatha 11901 5.5 4.0 MG Abandoned on the Wild Frontier Jackson, Dave/Neta 6030 6.0 8.0 UG Abduction, The Newth, Mette 101 5.9 3.0 MG Abel's Island Steig, William 11577 4.7 7.0 MG Absolutely Normal Chaos Creech, Sharon 5252 4.2 6.0 UG Ace Hits the Big Time Murphy, Barbara 5253 5.6 2.0 UG Acorn People, The Jones, Ron 102 6.6 10.0 MG Across Five Aprils Hunt, Irene 6901 4.6 8.0 UG Across the Grain Ferris, Jean 18801 6.3 10.0 UG Across the Lines Reeder, Carolyn 17602 5.5 4.0 MG Across the Wide and Lonesome Prairie: The Oregon Trail Diary of Hattie Campbell Gregory, Kristiana 11701 4.8 8.0 UG Adam and Eve and Pinch-Me Johnston, Julie 16702 9.4 42.0 UG Adam Bede Eliot, George 1 6.5 9.0 MG Adam of the Road Gray, Elizabeth 64976 5.9 5.0 MG Adara Gormley, Beatrice 8601 7.7 2.0 UG Adventure of the Speckled Band, The Doyle, Arthur 501 6.6 18.0 MG Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, The (Unabridged) Twain, Mark 52301 8.1 11.0 MG Adventures of Robin Hood, The (Unabridged) Green, Roger 502 8.1 12.0 MG Adventures of Tom Sawyer, The (Unabridged) Twain, Mark 8551 4.4 5.0 UG After the Bomb Miklowitz, Gloria 351 3.8 8.0 MG After the Dancing Days Rostkowski, Margaret 352 -

SF COMMENTARY 81 40Th Anniversary Edition, Part 2

SF COMMENTARY 81 40th Anniversary Edition, Part 2 June 2011 IN THIS ISSUE: THE COLIN STEELE SPECIAL COLIN STEELE REVIEWS THE FIELD OTHER CONTRIBUTORS: DITMAR (DICK JENSSEN) THE EDITOR PAUL ANDERSON LENNY BAILES DOUG BARBOUR WM BREIDING DAMIEN BRODERICK NED BROOKS HARRY BUERKETT STEPHEN CAMPBELL CY CHAUVIN BRAD FOSTER LEIGH EDMONDS TERRY GREEN JEFF HAMILL STEVE JEFFERY JERRY KAUFMAN PETER KERANS DAVID LAKE PATRICK MCGUIRE MURRAY MOORE JOSEPH NICHOLAS LLOYD PENNEY YVONNE ROUSSEAU GUY SALVIDGE STEVE SNEYD SUE THOMASON GEORGE ZEBROWSKI and many others SF COMMENTARY 81 40th Anniversary Edition, Part 2 CONTENTS 3 THIS ISSUE’S COVER 66 PINLIGHTERS Binary exploration Ditmar (Dick Jenssen) Stephen Campbell Damien Broderick 5 EDITORIAL Leigh Edmonds I must be talking to my friends Patrick McGuire The Editor Peter Kerans Jerry Kaufman 7 THE COLIN STEELE EDITION Jeff Hamill Harry Buerkett Yvonne Rousseau 7 IN HONOUR OF SIR TERRY Steve Jeffery PRATCHETT Steve Sneyd Lloyd Penney 7 Terry Pratchett: A (disc) world of Cy Chauvin collecting Lenny Bailes Colin Steele Guy Salvidge Terry Green 12 Sir Terry at the Sydney Opera House, Brad Foster 2011 Sue Thomason Colin Steele Paul Anderson Wm Breiding 13 Colin Steele reviews some recent Doug Barbour Pratchett publications George Zebrowski Joseph Nicholas David Lake 16 THE FIELD Ned Brooks Colin Steele Murray Moore Includes: 16 Reference and non-fiction 81 Terry Green reviews A Scanner Darkly 21 Science fiction 40 Horror, dark fantasy, and gothic 51 Fantasy 60 Ghost stories 63 Alternative history 2 SF COMMENTARY No. 81, June 2011, 88 pages, is edited and published by Bruce Gillespie, 5 Howard Street, Greensborough VIC 3088, Australia. -

III. Adopt the Agenda of the Regular Meeting of June 20. 2018 VIII

BOARD MEETING: Regular DATE: Wednesday, June 20,2018 TIME: 6:30 p.m. PLACE: Naples High School Cafeteria I. Meeting Called to Order II. Roll Call III. Adopt the Agenda of the Regular Meeting of June 20. 2018 (Board Action) IV. Executive Session (Board Action) V. Pledge of Allegiance VI. Public Comments: The Board of Education invites you, the residents of our school community, to feel comfortable in sharing matters of interest or concern that you might have with us. The Board President will be happy to recognize those of you who wish to speak. We would ask that you come forward and please identity yourself before presenting your thoughts. Those items brought to the attention of the Board during this time may be taken under consideration for future response or action. {Individual comments will be limited to three minutes.) As a matter of courtesy, we ask that issues related to specific School District personnel or students be brought to the attention of the Superintendent of Schools privately. Thank you for this consideration. Board Response: The Board of Education is committed to keeping communication open and transparent. The Board of Education President will be working with the Board and the Superintendent to make every effort to respond to public comments directed to the Board of Education at previous meetings, during the next scheduled meeting. VII. Points of Interest VIII. Superintendent Recognitions & Updates • Welcome Owen Keimedy Have a Great Summer • Handbook for Coaches IX. Administrative Reports • Elementary Principal Director of Pupil Personnel Services • Secondary Principal X. Contractual Agreement • Superintendent's Contract (Board Action) . -

Urban Fantasy Secret Societies and Shady Characters Fairy Tales And

Urban Fantasy Magical Realism —Ninth House by Leigh Bardugo —The House of the Spirits by Isabel Allende —Storm Front by Jim Butcher —Summerlong by Peter S. Beagle —Highfire by Eoin Colfer —Ficciones by Jorge Luis Borges —The City We Became by N.K. Jemisin —The Book of Hidden Things by Francesco Dimitri —Darkfever by Karen Marie Moning —A Green and Ancient Light by Frederic S. Durbin —Witchmark by C.L. Polk —Like Water for Chocolate by Laura Esquivel —One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Secret Societies and Márquez Shady Characters —Exit West by Mohsin Hamid —The Shape of Water by Guillermo del Toro —The Invisible Library by Genevieve Cogman —The Binding by Bridget Collins —Lent by Jo Walton —The House in the Cerulean Sea by TJ Klune Graphic Novels —The Lies of Locke Lamora by Scott Lynch —American Gods by Neil Gaiman —The Night Circus by Erin Morgenstern —Neverwhere by Neil Gaiman —The Starless Sea by Erin Morgenstern —Monstress by Marjorie Liu —A Darker Shade of Magic by V.E. Schwab —The Complete ElfQuest by Wendy Pini Fairy Tales and —Nimona by Noelle Stevenson Mythology —Rat Queens by Kurtis J. Wiebe —The Bear and the Nightingale by Katherine Short Stories Arden —The People in the Castle by Joan Aiken —The Blue Salt Road by Joanne M. Harris —The Bloody Chamber by Angela Carter —A Pocketful of Crows by Joanne M. Harris Explore the amazing worlds of —Norse Mythology by Neil Gaiman —The Snow Child by Eowyn Ivey Fantasy! From far off lands full of —Confessions of an Ugly Stepsister by Gregory —Get in Trouble by Kelly Link magic and wonder to the Maguire —Dreams of Distant Shores by Patricia A. -

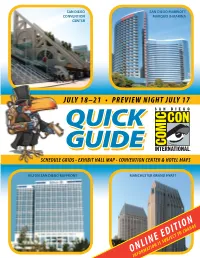

Quick Guide Is Online

SAN DIEGO SAN DIEGO MARRIOTT CONVENTION MARQUIS & MARINA CENTER JULY 18–21 • PREVIEW NIGHT JULY 17 QUICKQUICK GUIDEGUIDE SCHEDULE GRIDS • EXHIBIT HALL MAP • CONVENTION CENTER & HOTEL MAPS HILTON SAN DIEGO BAYFRONT MANCHESTER GRAND HYATT ONLINE EDITION INFORMATION IS SUBJECT TO CHANGE MAPu HOTELS AND SHUTTLE STOPS MAP 1 28 10 24 47 48 33 2 4 42 34 16 20 21 9 59 3 50 56 31 14 38 58 52 6 54 53 11 LYCEUM 57 THEATER 1 19 40 41 THANK YOU TO OUR GENEROUS SHUTTLE 36 30 SPONSOR FOR COMIC-CON 2013: 32 38 43 44 45 THANK YOU TO OUR GENEROUS SHUTTLE SPONSOR OF COMIC‐CON 2013 26 23 60 37 51 61 25 46 18 49 55 27 35 8 13 22 5 17 15 7 12 Shuttle Information ©2013 S�E�A�T Planners Incorporated® Subject to change ℡619‐921‐0173 www.seatplanners.com and traffic conditions MAP KEY • MAP #, LOCATION, ROUTE COLOR 1. Andaz San Diego GREEN 18. DoubleTree San Diego Mission Valley PURPLE 35. La Quinta Inn Mission Valley PURPLE 50. Sheraton Suites San Diego Symphony Hall GREEN 2. Bay Club Hotel and Marina TEALl 19. Embassy Suites San Diego Bay PINK 36. Manchester Grand Hyatt PINK 51. uTailgate–MTS Parking Lot ORANGE 3. Best Western Bayside Inn GREEN 20. Four Points by Sheraton SD Downtown GREEN 37. uOmni San Diego Hotel ORANGE 52. The Sofia Hotel BLUE 4. Best Western Island Palms Hotel and Marina TEAL 21. Hampton Inn San Diego Downtown PINK 38. One America Plaza | Amtrak BLUE 53. The US Grant San Diego BLUE 5. -

TOP RUSSIAN AUTHOR ARKADY STRUGATSKY DIES INSIDE January 28Th Is the ISFA Annual General EDITORIAL 2 Meeting

NEWSLETTER OF THE IRISH SCIENCE FICTION ASSOCIATION ISSUE NO 69_________________ JANUARY 1992_______________ISSN 0791-3966 TOP RUSSIAN AUTHOR ARKADY STRUGATSKY DIES INSIDE January 28th is the ISFA Annual General EDITORIAL 2 Meeting. It’s in the Horse and Tram on Eden Quay, at 8 p.rn. This is a necessary evil - it’s a WRITERS & WRITING 2 forum for airing views, electing a new committee, and discussing the future of the FANS 4 Association. Over the past year the CONVENTIONS 5 Association has succeeded in its aims of bringing science fiction to die attention of die CLUBS 5 public in many ways: SfEx had an attendance of over 700, and featured excellent and varied FANZINES 6 artwork and sculpture by both professional FIRST CONTACT 7 and amateur artists; FTL has progressed from a photocopied fanzine to a fully-printed ROBERT HOLDSTOCK magazine which promises a lot for the future; INTERVIEWED 8 the Aisling Gheal Short Story Competition was sponsored by Harry Harrison, won by REVIEWS 12 Brendan Farrell (who is now head of distribution for Fl'Ll) and attracted over 60 FIVE BOOKS 18 entries; our meetings ranged from a simple THE COMIC COLUMN 19 book auction to ‘An Evening With Clive Barker’ and ‘An Evening Widi Terry Brooks’; UPCOMING ISFA EVENTS 20 we also had celebrations of Blake’s 7 and Star Trek; the Newsletter expanded from eight pages to twenty-four, and the topics covered PRODUCTION widiin it likewise broadened; Octocon, run by ISFA members, had over 600 attendees and EDITOR: Brendan Ryder was a huge success. The future for the ISFA DESIGN: Mark Smullen & Dave McKane looks bright - come to the AGM and tell us DESIGN FACILITIES: VisArt Advertising where you want to see it goingl PUBLISHED BY the I1USH SCIENCE FICTION ASSOCIATION, 30 Beverly Downs, KnoMyon Road, Templeogue, WRITERS & Dublin 16, Telephone 934712, Fax 61.1166. -

Fantasy Series

Fantasy Series Albert, Susan Wittig 41. Ghost Writer in the Sky 5. Mirror Sight Cottages Tales of Beatrix Potter 42. Fire Sail 6. Firebrand 1. The Tale of Hill Top Farm 43. Jest Right Brooks, Terry 2. The Tale of Holly How 44. Skeleton Key Magic Kingdom of Landover 3. The Tale of Cuckoo Brow Baker, Mishell 1. Magic Kingdom for Sale Wood Arcadia Project Sold! 4. The Tale of Hawthorn 1. Borderline 2. The Black Unicorn House 2. Phantom Pains 3. Wizard at Large 5. The Tale of Briar Bank 3. Impostor Syndrome 4. The Tangle Box 6. The Tale of Applebeck Bradbury, Ray 5. Witches’ Brew Orchard Douglas Spaulding 6. A Princess of Landover 7. The Tale of Oat Cake Crag 1. Dandelion Wine Word And Void Trilogy 8. The Tale of Castle Cottage 2. Something Wicked This 1. Running with the Demon Anthony, Piers Way Comes 2. A Knight of the Word Mode 3. Farewell Summer 3. Angel Fire East 1. Virtual Mode Bradley, Marion Zimmer Shannara (series publication order) 2. Fractal Mode Avalon Shannara 3. Chaos Mode 1. The Mists of Avalon First King of Shannara 4. Dooon Mode 2. The Forest House 1. The Sword of Xanth 3. Lady of Avalon Shannara 1. A Spell for Chameleon 4. Priestess of Avalon 2. The Elfstones of 2. The Source of Magic 5. Ancestors of Avalon Shannara 3. Castle Roogna 6. Ravens of Avalon 3. The Wishsong of 4. Centaur Aisle 7. Sword of Avalon Shannara 5. Ogre, Ogre Darkover (publication order) Heritage of Shannara 6. Night Mare 1. -

Fantasy Series

BRAILLE AND TALKING BOOK LIBRARY (800) 952-5666; btbl.ca.gov; [email protected] Fantasy Series Completed or on-going fantasy series by some of the biggest names in the genre. To order any of these titles, contact the library by email, phone, mail, in person, or order through our online catalog. Most titles can be downloaded from BARD. Dark Legacy of Shannara by Terry Brooks The first book is Wards of Faerie Next books in the series: Bloodfire Quest; Witch Wraith Read by Mary Kane 12 hours, 21 minutes Druid Aphenglow Elessedil has spent a year in the archives searching for a clue to the lost Elfstones. In the diary of a young Elven girl, Aphenglow finds the hint that launches her quest to recover the stones. Some violence. 2012. Download from BARD: Wards of Faerie Also available on digital cartridge DB075350 Shannara Series by Terry Brooks The first book is First King of Shannara Next books in the series: The Sword of Shannara; Elfstones of Shannara; Wishsong of Shannara Read by James DeLotel 19 hours, 51 minutes In this prequel to The Sword of Shannara (DB 11046), Bremen the Druid, who has been expelled from Paranor for studying the magical sciences, learns of an advancing army of trolls led by Brona, the Warlock Lord. Bremen now struggles to unite the peoples of the Four Lands and to find a new weapon that will foil Brona’s evil plans. Download from BARD: The First King Also available on digital cartridge DB043233 The Codex Alera by Jim Butcher The first book is Furies of Calderon Next books in the series: Academ’s Fury; Cursor’s Fury; Captain’s Fury; Princep’s Fury; First Lord’s Fury Read by Jack Fox 17 hours, 51 minutes To defend themselves against invaders, the people of Alera bond with the elemental furies of earth, wood, fire, water, air, and metal. -

Fantasy Series

Fantasy Series Albert, Susan Wittig 41. Ghost Writer in the Sky 3. The High King’s Tomb Cottages Tales of Beatrix Potter 42. Fire Sail 4. Blackveil 1. The Tale of Hill Top Farm Baker, Mishell 5. Mirror Sight 2. The Tale of Holly How Arcadia Project 6. Firebrand 3. The Tale of Cuckoo Brow 1. Borderline Brooks, Terry Wood 2. Phantom Pains Magic Kingdom of Landover 4. The Tale of Hawthorn 3. Impostor Syndrome 1. Magic Kingdom for Sale House Barron, T.A. Sold! 5. The Tale of Briar Bank The Lost Years of Merlin 2. The Black Unicorn 6. The Tale of Applebeck 1. The Lost Years of Merlin 3. Wizard at Large Orchard 2. The Seven Songs of Merlin 4. The Tangle Box 7. The Tale of Oat Cake Crag 3. The Fires of Merlin 5. Witches’ Brew 8. The Tale of Castle Cottage 4. The Mirror of Merlin 6. A Princess of Landover Anthony, Piers 5. The Wings of Merlin Shannara Mode Bradbury, Ray First King of Shannara 1. Virtual Mode Douglas Spaulding (Prequel) 2. Fractal Mode 1. Dandelion Wine 1. The Sword of Shannara 3. Chaos Mode 2. Farewell Summer 2. The Elfstones of Shannara 4. Dooon Mode Bradley, Marion Zimmer 3. The Wishsong of Shannara Xanth Avalon The Heritage of Shannara 1. A Spell for Chameleon 1. The Mists of Avalon 1. The Scions of Shannara 2. The Source of Magic 2. The Forest House 2. The Druid of Shannara 3. Castle Roogna 3. Lady of Avalon 3. The Elf Queen of 4. Centaur Aisle 4.