Legislative Council

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Merchants of Menace: the True Story of the Nugan Hand Bank Scandal Pdf, Epub, Ebook

MERCHANTS OF MENACE: THE TRUE STORY OF THE NUGAN HAND BANK SCANDAL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Peter Butt | 298 pages | 01 Nov 2015 | Peter Butt | 9780992325220 | English | Australia Merchants of Menace: The True Story of the Nugan Hand Bank Scandal PDF Book You They would then put it up for sale through a Panama-registered company at full market value. We get a close-up of his fearsome Vietnam exploits in interviews with Douglas Sapper, a combat buddy from the days of Special Forces training. Take it, smoke it, give yourself a shot, just get rid of it. No trivia or quizzes yet. With every sale Mike and Bud earned a tidy 25 per cent commission. In fact, throughout military training the thing you noticed about Michael was that he was driven. But he dropped out and took a position 22 2 Jurisprudence is crap with the Canadian public service, giving him an income with which he could feed his penchant for fast cars, girls and gliding lessons. Sapper had contacts all the way up and down the Thai food chain; he warned Hand of the obvious perils of setting up business in that part of the world: Chiang Mai is the Wild West, the hub of good and evil, but mostly evil. It was evident that the embryonic bank had been outlaying far more money than it was earning: It became very clear to me that Nugan Hand had the trappings of a bank, but it was so much window dressing. During the Vietnam War, he dished out drugs, legal and illegal, to his military colleagues and friends, including Rolling Stone journalist Hunter S Thompson. -

Obama-C.I.A. Links

o CO Dispatch "The issue is not issues; the issue is the system" —Ronnie Dugger Newsletter of the January-February Boston-Cambridge Alliance for Democracy 2011 Barack Obama is neither weak nor is he stupid. He knows exactly what he is doing. He is cynically carrying out the pre- cise bidding of his corporate/military masters, while rhetorically faking-out everyday Black, White, Brown, Red, and Yellow people with his endless bait and switch tactics. —Larry Pinkney, Black Commentator Barack Obama (right) with his mother Ann Dunham, step-father Lolo Soetoro, and infant half-sister Maya. Dunham worked in several CIA COMMUNITY NOTES front groups in Hawai'i and Indonesia, and Colonel Soetoro helped Don't be left out! Join the BCA/NorthBridge planning group! overthrow Indonesia's president Sukarno in a CIA-sponsored coup. Our next meeting will be Tuesday, 4 January, 7:30, in the AfD After graduating from Columbia University, Obama worked for a CIA- office at 760 Main St., Waltham MA. Info: 781-894-1179. sponsored international business seminar group. Current projects: "bottled water ban in Concord "supporting ousted city councilor Chuck Turner "building support for Move Obama-C.I.A. Links to Amend (anti-corporate-personhood) and progressive Self and Principal Relatives All Involved campaign finance legislation "participatory budgeting by Sherwood Ross, grantlawrence.blogspot.com, 2 Sep 2010 conference in April "developing a trade advisory committee to seed and bird-dog the new MA citizen trade commission. RESIDENT OBAMA—AS WELL AS HIS MOTHER, FATHER, STEP- Turn to Page 16 for notes on these and other local matters.. -

Nugan Hand Bank

Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Search Nugan Hand Bank From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from Nugan hand bank) Main page Contents Nugan Hand Bank was an Australian merchant bank that collapsed in 1980 in sensational Featured content circumstances amidst rumours of involvement by the Central Intelligence Agency and organized Current events crime. The bank was co-founded in 1973 by Australian lawyer Francis John Nugan and US ex- Random article Green Beret Michael Jon Hand, and had connections to a range of US military and intelligence Donate to Wikipedia figures, including William Colby, who was CIA director from 1973 to 1976. Nugan's apparent Wikimedia Shop suicide in January 1980 precipitated the collapse of the bank, which regulators later judged never Interaction to have been solvent. Hand disappeared in mid-1980. Help About Wikipedia Contents [hide] Community portal 1 Founding Recent changes 2 Scandal and collapse Contact page 3 Investigations Tools 4 References What links here 5 Sources Related changes 6 External links Upload file Special pages Permanent link Founding [edit] open in browser PRO version Are you a developer? Try out the HTML to PDF API pdfcrowd.com [edit] Page information Founding Wikidata item Nugan Hand Ltd. was founded in Sydney in 1973 by Australian lawyer Francis John "Frank" Nugan Cite this page (who was reputedly associated with the Mafia in Griffith, New South Wales) and former U.S. Green Print/export Beret Michael Jon "Mike" Hand who had experience in the Vietnam War (after which he began Create a book training Hmong guerillas in Northern Laos under CIA aegis, an experience alleged to account for Download as PDF his ties to the "Golden Triangle" heroin trade). -

Legislative Council 8/06/88 INDEPENDENT COMMISSION AGAINST CORRUPTION BILL (NO

Legislative Council 8/06/88 INDEPENDENT COMMISSION AGAINST CORRUPTION BILL (NO. 2) Second Reading Extract The Hon. 1. M. MACDONALD [11.49]: I rise on this bill because I believe passionately in its need but deplore many of its means. In the late 1970s while working in the Attorney General's Department I concentrated my research on the issues of organized crime, the illicit drug industry, and their hideous results. Of particular concern and interest to me was the Nugan Hand Bank and its sinister links with many sections of our society. As a result of this intensive research into the dark side of Australian life, I have for years advocated a State crimes commission and supported numerous initiatives to curtail organized crime and corruption. These have included the internal affairs branch of the Police Department, strong powers of the Ombudsman, the State Drug Crimes Commission, and the Judicial Conduct Division. Running parallel to the emergence of effective anti-crime and corruption measures has been my deep-seated concern at the consistent erosion of civil liberties that seem part and parcel of our fight against crime. Legislators, in their enthusiasm, are adopting laws in many countries which undermine hundreds of years of natural justice. While this is done in an eagerness to stamp out the illicit drug industry, in many instances its effects can be unacceptable to society. This bill, as I will endeavour to demonstrate, does just that: it continues a trend into dangerous directions which challenge the very concept of democracy and freedom that Australians have fought and died for. -

Marijuana Australiana

Marijuana Australiana Marijuana Australiana: Cannabis Use, Popular Culture, and the Americanisation of Drugs Policy in Australia, 1938 - 1988 John Lawrence Jiggens, BA Centre for Social Change Research Carseldine Campus QUT Submitted in requirement for the degree, Doctor of Philosophy, April 2004 1 Marijuana Australiana KEY WORDS: Narcotics, Control of—Australia, Narcotics and crime—Australia, Cannabis use— Australia, Popular Culture—Australia, Drugs policy—Australia, Organised crime— Queensland, New South Wales, Cannabis prohibition—Australia, Police corruption—Queensland, New South Wales, the counter-culture—Australia, Reefer Madness—Australia, the War on Drugs—Australia, Woodward Royal Commission (the Royal Commission into Drug Trafficking), the Williams Royal Commission (Australian Royal Commission into Drugs), the Fitzgerald Inquiry, the Stewart Royal Commission (Royal Commission into Nugan Hand), Chlorodyne, Cannabis— medical use, cannabis indica, cannabis sativa, Gough Whitlam, Richard Nixon, Donald Mackay, Johannes Bjelke- Petersen, Terry Lewis, Ray Whitrod, Fast Buck$, Chris Masters, John Wesley Egan, the Corset Gang, Murray Stewart Riley, Bela Csidei, Maurice Bernard 'Bernie' Houghton, Frank Nugan, Michael Jon Hand, Sir Peter Abeles, Merv Wood, Sir Robert Askin, Theodore (Ted) Shackley, Fred Krahe, James (Jimmy) Bazley, Gianfranco Tizzoni, Ken Nugan, Brian Alexander. 2 Marijuana Australiana ABSTRACT The word ‘marijuana’ was introduced to Australia by the US Bureau of Narcotics via the Diggers newspaper, Smith’s Weekly, in 1938. Marijuana was said to be ‘a new drug that maddens victims’ and it was sensationally described as an ‘evil sex drug’. The resulting tabloid furore saw the plant cannabis sativa banned in Australia, even though cannabis had been a well-known and widely used drug in Australia for many decades. -

13 March 1986 ASSEMBLY 167

Questions without Notice 13 March 1986 ASSEMBLY 167 Thursday, 13 March 1986 The SPEAKER (the Hon. C. T. Edmunds) took the chair at 10.35 a.m. and read the prayer. QUESTIONS WITHOUT NOTICE TRAVEL ENTITLEMENTS Mr PESCOTT (Bennettswood)-I refer the Premier to his approval for official overseas travel last November of the Victorian Tourism Commission's senior project development consultant, Mr David Faggetter, and ask: why did the Premier approve of Mr Faggetter using a free airline ticket on that trip, given the Premier's own standards on overseas travel, and what does he intend to do about information provided to his department that unauthorized expenditure on this trip may have exceeded $40001 Mr CAIN (Premier)-The letter to which the honourable member refers has come to my notice and it has also come to the notice of the Deputy Premier, the Minister responsible, and it is presently under consideration by him. I am aware of the intense interest that has been taken by the honourable member in these matters and I just hope that when he is looking into them he takes some time to compare the sets of guidelines and requirements that presently exist with those that existed under the previous Government, because we have imposed standards on members of Parliament and on public office holders who claim travel and other expenses from the public purse. That has not been easy after the rorts that went on under the previous Government. It has been very difficult indeed, as honourable members would appreciate, and, although I will not cite instances chapter and verse today, I could cite a whole range of rorts, such as Parliamentary committees which, under the previous Government, contrived trips. -

NSW Local Government Investment in Cdos

NSW Local Government Investment in CDOs: A Corporate Governance Perspective A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Gregory Evan Jones. Bachelor of Commerce (Accounting and Business Management) University of Tasmania Masters of Accountancy-Research University of Wollongong From University of Western Sydney School of Business 2013 Dedication For my wonderful wife Hazel; In recognition of her generous love, support and encouragement (and forbearance). i Acknowledgements Page I wish to thank my supervisors Associate Professor Anne Abraham and Associate Professor Phil Ross for their generous assistance and allocation of time. Anne’s enthusiasm and interest provided me with the impetus to continue when things became difficult, and the direction when events began to overwhelm me. Our working relationship has developed into a friendship that I hope will continue. Phil’s support and assistance throughout the process, particularly in relation to contacts within the Local Government community is greatly appreciated I also wish to thank Dr Graham Bowrey and Dr Ciorstan Smark for their advice and assistance and for being willing to listen to my complaints (and plying me with coffee). It is with an enormous amount of gratitude and appreciation that I would like to acknowledge the love, support, patience and encouragement given to me by my wife Hazel and my children, Lachlan, Rachel and Amy. Their generosity in allowing me to devote time to this research is greatly appreciated and highly valued. Additionally I would like to thank the individuals who generously gave of their time and consented to be interviewed for this research. -

The True Story of the Nugan Hand Bank Scandal Pdf

FREE MERCHANTS OF MENACE: THE TRUE STORY OF THE NUGAN HAND BANK SCANDAL PDF Peter Butt | 298 pages | 01 Nov 2015 | Peter Butt | 9780992325220 | English | Australia Merchants of Menace | Book The only new Peter Butt has spent three decades as a documentary filmmaker specialising in history. Peter Butt. Guns, drug money and the CIA These were not your average bankers. This was not your average bank. Infollowing the mysterious death of Australian merchant banker, Frank Nugan, his New York-born partner, Michael Hand, brazenly ordered the destruction of the bank's records. Hand then disappeared from Sydney and hasn't been seen since. Among the ruins of the Nugan Hand global financial empire, investigators uncovered astonishing evidence of gunrunning, money laundering for drug traffickers and connections to the CIA. When the FBI and Merchants of Menace: The True Story of the Nugan Hand Bank Scandal Royal Commission failed to join the dots, those intimately involved with the case suspected a cover up. Brimming with chilling new evidence and powerful testimonies, Merchants of Menace cracks open the sensational Nugan Hand story and goes on the hunt for the world's most elusive corporate fugitive I said 'I don't know. But whatever it was, it was the lynchpin that started everything crumbling. Merchants of Menace - The True Story of the Nugan Hand Bank Scandal (preview) by cracker - Issuu Peter Butt is an Australian investigative filmmaker. Over the last three decades he has produced and directed major history series and dozens of documentary specials for local and international broadcasters. First Published in Blackwattle Press Sydney www. -

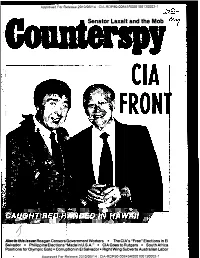

Counterspy: Cia Front

Approved For Release 2010/06/14: CIA-RDP90-00845R000100130002-1 SenatorLaxalt and the Mob 1 Alsolnthis Issue: Reagan Censors Government Workers • The CIA's "Free"Elections in El Salvador • Philippine Elections "Made in U.S.A." • CIA Goesto Rutgers • South Africa Positions for Olympic Gold• Corruption in El Salvador• Right Wing Subverts Australian Labor Approved For Release 2010/06/14: CIA-RDP90-00845R000100_1�0002-1 Approved For Release 2010/06/14: CIA-RDP90-00845R000100130002-1 2 June-August 1984 Counterspy Approved For Release 2010/06/14: CIA-RDP90-00845R000100130002-1 Editor COUNTERSPY JUNE-AUGUST 1984 John Kelly FEATURES Board of Advisors Cover to Cover: Rewald's CIA Story Dr. Walden Bello by John Kelly Congressional Lobby When Rewald's investment company went bankrupt, furious In Director, Philippine 8 vestors filed suit against Rewald-and the CIA- to recover Support Committee their money. For Rewald claims his company was a CIA front, John Cavanagh cultivating wealthy individuals as CIA contacts through money Economist making schemes. Dr. Noam Chomsky Paul Laxalt's Debt to the Mob Professor at MIT by Murray Waas Peace Activist Paul Laxalt-U.S. Senator, close friend and personal confidant 18 of the President, and Chairman of the Republican national Com Dr. Joshua Cohen Assistant Professor, MIT mittee-accepted a $950,000 loan arranged by organized crime friends. Joan Coxsedge Member of Parliament World Bank State of Victoria, Australia A poem by Arjun Makhijani Konrad Ege 27 Journalist Ruth Fitzpatrick ... And Lifetime Censorship for All Member, Steering Committee by Angus MacKenzie of the Religious Task Force Congress thought it had stopped a new rule subjecting govern on Central America 28 ment workers to censorship for life. -

CHAPTER 3 Are Concerned, They Act As Criminal Actors Themselves

Transnational crime and the interface between legal and illegal actors : the case of the illicit art and antiquities trade Tijhuis, A.J.G. Citation Tijhuis, A. J. G. (2006, September 6). Transnational crime and the interface between legal and illegal actors : the case of the illicit art and antiquities trade. Wolf Legal Publishers. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/4551 Version: Corrected Publisher’s Version Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/4551 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). CHAPTER3 INDIVIDUALS AND LEGITIMATE ORGANIZATIONS AS INTERFACE In the previous chapter a new the typology of interfaces was developed based on the analyses of the interface typology of Passas with which chapter two started. Many concrete examples of a number of different interfaces between legal and illegal were given. On both sides of the line between legal and illegal, the actors involved are usually ‘organizations’ in one way or another. To be sure, organizations are not meant in a traditional sense here. They also include loose networks of criminals. These criminal organizations or networks usually consist of groups of people who are engaged in some transnational crime together, that does not consist of only a one-off collaboration. In addition to the fact that actors are usually seen as organizations, the interfaces are thought to be between legal and illegal actors. They are thus interpreted as a relationship, for example, the interface between arms producers and rebel groups in some far away country. -

13 September 1988

2648 Tuesday, 13 September 1988 THE SPEAKER (Mr Bamnett) took the Chair at 2. 15 pm, and read prayers. PETITION Crime - Vandalism MR WATT (Albany) (2.17 pm]: In accordance with the right of every citizen to petition the Parliament, I have two interesting petitions. The first is worded as follows - To the Honourable, the Speaker and Members of the Legislative Assembly of the Parliament of Western Australia in Parliament assembled. We, the undersigned request that second offender vandals be confined to "the stocks" and paraded for specific periods near their homes or supermarkets in the vicinity of their crimes. They will at all timres be supervised by a prison officer. No tomatoes, eggs or anything else may be thrown. Your petitioners therefore humbly pray that you will give this matter your earnest consideration and your petitioners, as in duty bound, will ever pray. Mr Peter Dowding: Is this the Liberal Party's crime platform? Mr WATT: No, it is not, but it has a message. The SPEAKER: Did the member manage to obtain sufficient signatures for that petition? Mr WAIT: I did not collect any signatures. Mr Speaker, but the author collected 97 signatures. I certify that it conforms to the Standing Orders of the Legislative Assembly. The SPEAKER: I direct that the petition be brought to the Table of the House. [See petition No 61 .] PETITION Property Owners - Powers MR WATT (Albany) [2.19 pm]: The second petition by the same author reads as follows - To the Honourable, the Speaker and Members of the Legislative Assembly of the Parliament of Western Australia in Parliament assembled. -

PROJECT ICONE/MANILA: an Evaluation PROJECT ICONE/MANILA: an Evaluation

PROJECT ICONE/MANILA: An Evaluation PROJECT ICONE/MANILA: An Evaluation Contract Number LAC-0044-C-00-1021-00 Project Number 598-0044/936-1406 Amount Obligated: $15,000 By William B. Miller President, TransTech Services USA Alexandria, Virginia June 8, 1981 PROJECT ICONE/MANILA: An Evaluation TABLE OF CONTENTS I. SUMMARY .. .... 1 II. THE BACKGROUND OF PROJECT ICONE/MANILA. 5 III. THE COSTS OF PROJECT ICONE/MANILA . 8 IV. THE RESULTS OF PROJECT ICONE/MANILA . 11 A. General. ... ... ... ... ... 11 B. Business Possibilities . ... ... 12 C. Overall Comment...... .. ... .. 14 D. Philippine Government Reactions. .. .. 18 V. AN EVALUATION OF PROJECT ICONE/MANILA: CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS . 22 A. Conclusions. ... .. ... ... .. 22 B. Recommendations. ... .. ... ... 27 APPENDICES A. Listing of Participants at Project ICONE/Manila B. Conference Agenda, Project ICONE/Manila C. A Note on Methodology D. Tabular Summary, Responses of Participants Interviewed PROJECT ICONE/MANILA: An Evaluation I. Summary An International Congress on New Enterprise (ICONE) was presented in Manila, Philippines, June 24-29, 1979. The Con gress was part of what was designed as an international cooper ative effort to establish more small and medium-scale enter prises (SME) in the developing countries, enhancing their proven role in creating jobs rapidly and at low cost. The Congress was Phase II of what was conceived as a three phase effort involving identification of potentially promising joint venture projects in a host country or countries and the recruitment of interested developed/developing country entre preneurs (Phase I), the assembling of these entrepreneurs at an international working forum to consider the identified projects and to share interests and experiences (Phase II), and (Phase III) the provision of ongoing project development support as well as small business management and entrepreneurial training services in cooperation with in-country institutions.