Arxiv:1604.01764V2 [Astro-Ph.GA] 26 Jul 2016 Star-Formation Rates, Typically Orders of Magnitude Be- (E.G., Mitchell Et Al

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Molecular Gas in the Elliptical Galaxy NGC 759 Cessfully Reproduce the Observed Properties (Hernquist & Barnes 1991)

A&A manuscript no. (will be inserted by hand later) ASTRONOMY AND Your thesaurus codes are: ASTROPHYSICS 09.13.2; 11.05.1; 11.09.1; 11.09.4; 11.11.1; 6.8.2018 Molecular gas in the elliptical galaxy NGC 759 Interferometric CO observations T. Wiklind1, F. Combes2, C. Henkel3, F. Wyrowski3,4 1 Onsala Space Observatory, S–43992 Onsala, Sweden 2 DEMIRM Observatoire de Paris, 61 Avenue de l’Observatoire, F–75014 Paris, France 3 Max-Planck-Institut f¨ur Radioastronomie, Auf dem H¨ugel 69, D–53121 Bonn, Germany 4 Physikalisches Institut der Universit¨at zu K¨oln, Z¨ulpicher Strasse 77, D–50937 K¨oln, Germany Received date; Accepted date Abstract. We present interferometric observations of CO(1–0) emission in the elliptical galaxy NGC 759 with an angular resolution of 3 ′′. 1 2 ′′. 3 (990 735pc at a distance × × 9 1. Introduction of 66Mpc). NGC759 contains 2.4 10 M⊙ of molecular × gas. Most of the gas is confined to a small circumnuclear Faber & Gallagher (1976) found the apparent absence of ◦ ring with a radius of 650 pc with an inclination of 40 . The an interstellar medium (ISM) in elliptical galaxies surpris- −2 maximum gas surface density in the ring is 750 M⊙ pc . ing since mass loss from evolved stars should contribute as 9 10 Although this value is very high, it is always less than much as 10 10 M⊙ of gas to the ISM during a Hubble or comparable to the critical gas surface density for large time. Today− we know that ellipticals do contain an ISM, scale gravitational instabilities. -

The MASSIVE Survey-VIII. Stellar Velocity Dispersion Profiles And

MNRAS 000,1{17 (2017) Preprint 26 October 2017 Compiled using MNRAS LATEX style file v3.0 The MASSIVE Survey - VIII. Stellar Velocity Dispersion Profiles and Environmental Dependence of Early-Type Galaxies Melanie Veale,1;2? Chung-Pei Ma,1;2? Jenny E. Greene,3 Jens Thomas,4 John P. Blakeslee,5 Jonelle L. Walsh,6 Jennifer Ito1 1Department of Astronomy, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA 2Department of Physics, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA 3Department of Astrophysical Sciences, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544, USA 4Max Plank-Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics, Giessenbachstr. 1, D-85741 Garching, Germany 5Dominion Astrophysical Observatory, NRC Herzberg Astronomy & Astrophysics, Victoria BC V9E2E7, Canada 6George P. and Cynthia Woods Mitchell Institute for Fundamental Physics and Astronomy, and Department of Physics and Astronomy, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843, USA Accepted XXX. Received YYY; in original form ZZZ ABSTRACT We measure the radial profiles of the stellar velocity dispersions, σ¹Rº, for 90 early-type galaxies (ETGs) in the MASSIVE survey, a volume-limited integral-field spectroscopic (IFS) galaxy survey targeting all northern-sky ETGs with absolute K-band magnitude > 11 MK < −25:3 mag, or stellar mass M∗ ∼ 4 × 10 M , within 108 Mpc. Our wide-field 10700×10700 IFS data cover radii as large as 40 kpc, for which we quantify separately the inner (2 kpc) and outer (20 kpc) logarithmic slopes γinner and γouter of σ¹Rº. While γinner is mostly negative, of the 56 galaxies with sufficient radial coverage to determine γouter we find 36% to have rising outer dispersion profiles, 30% to be flat within the uncertainties, and 34% to be falling. -

Download (1MB)

This is an Open Access document downloaded from ORCA, Cardiff University's institutional repository: http://orca.cf.ac.uk/136213/ This is the author’s version of a work that was submitted to / accepted for publication. Citation for final published version: Smith, Mark D., Bureau, Martin, Davis, Timothy A., Cappellari, Michele, Liu, Lijie, Onishi, Kyoko, Iguchi, Satoru, North, Eve V. and Sarzi, Marc 2021. WISDOM project - VI. Exploring the relation between supermassive black hole mass and galaxy rotation with molecular gas. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 500 , pp. 1933-1952. 10.1093/mnras/staa3274 file Publishers page: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/mnras/staa3274 <http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/mnras/staa3274> Please note: Changes made as a result of publishing processes such as copy-editing, formatting and page numbers may not be reflected in this version. For the definitive version of this publication, please refer to the published source. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite this paper. This version is being made available in accordance with publisher policies. See http://orca.cf.ac.uk/policies.html for usage policies. Copyright and moral rights for publications made available in ORCA are retained by the copyright holders. MNRAS 500, 1933–1952 (2021) doi:10.1093/mnras/staa3274 Advance Access publication 2020 October 22 WISDOM project – VI. Exploring the relation between supermassive black hole mass and galaxy rotation with molecular gas Mark D. Smith ,1‹ Martin Bureau,1,2 Timothy A. Davis ,3 Michele Cappellari ,1 Lijie Liu,1 Kyoko Onishi ,4,5,6 Satoru Iguchi ,5,6 Eve V. -

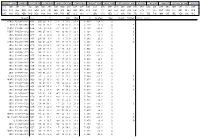

Bright Star Double Variable Globular Open Cluster Planetary Bright Neb Dark Neb Reflection Neb Galaxy Int:Pec Compact Galaxy Gr

bright star double variable globular open cluster planetary bright neb dark neb reflection neb galaxy int:pec compact galaxy group quasar ALL AND ANT APS AQL AQR ARA ARI AUR BOO CAE CAM CAP CAR CAS CEN CEP CET CHA CIR CMA CMI CNC COL COM CRA CRB CRT CRU CRV CVN CYG DEL DOR DRA EQU ERI FOR GEM GRU HER HOR HYA HYI IND LAC LEO LEP LIB LMI LUP LYN LYR MEN MIC MON MUS NOR OCT OPH ORI PAV PEG PER PHE PIC PSA PSC PUP PYX RET SCL SCO SCT SER1 SER2 SEX SGE SGR TAU TEL TRA TRI TUC UMA UMI VEL VIR VOL VUL Object ConRA Dec Mag z AbsMag Type Spect Filter Other names CFHQS J23291-0301 PSC 23h 29 8.3 - 3° 1 59.2 21.6 6.430 -29.5 Q ULAS J1319+0950 VIR 13h 19 11.3 + 9° 50 51.0 22.8 6.127 -24.4 Q I CFHQS J15096-1749 LIB 15h 9 41.8 -17° 49 27.1 23.1 6.120 -24.1 Q I FIRST J14276+3312 BOO 14h 27 38.5 +33° 12 41.0 22.1 6.120 -25.1 Q I SDSS J03035-0019 CET 3h 3 31.4 - 0° 19 12.0 23.9 6.070 -23.3 Q I SDSS J20541-0005 AQR 20h 54 6.4 - 0° 5 13.9 23.3 6.062 -23.9 Q I CFHQS J16413+3755 HER 16h 41 21.7 +37° 55 19.9 23.7 6.040 -23.3 Q I SDSS J11309+1824 LEO 11h 30 56.5 +18° 24 13.0 21.6 5.995 -28.2 Q SDSS J20567-0059 AQR 20h 56 44.5 - 0° 59 3.8 21.7 5.989 -27.9 Q SDSS J14102+1019 CET 14h 10 15.5 +10° 19 27.1 19.9 5.971 -30.6 Q SDSS J12497+0806 VIR 12h 49 42.9 + 8° 6 13.0 19.3 5.959 -31.3 Q SDSS J14111+1217 BOO 14h 11 11.3 +12° 17 37.0 23.8 5.930 -26.1 Q SDSS J13358+3533 CVN 13h 35 50.8 +35° 33 15.8 22.2 5.930 -27.6 Q SDSS J12485+2846 COM 12h 48 33.6 +28° 46 8.0 19.6 5.906 -30.7 Q SDSS J13199+1922 COM 13h 19 57.8 +19° 22 37.9 21.8 5.903 -27.5 Q SDSS J14484+1031 BOO -

October 2006

OCTOBER 2 0 0 6 �������������� http://www.universetoday.com �������������� TAMMY PLOTNER WITH JEFF BARBOUR 283 SUNDAY, OCTOBER 1 In 1897, the world’s largest refractor (40”) debuted at the University of Chica- go’s Yerkes Observatory. Also today in 1958, NASA was established by an act of Congress. More? In 1962, the 300-foot radio telescope of the National Ra- dio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) went live at Green Bank, West Virginia. It held place as the world’s second largest radio scope until it collapsed in 1988. Tonight let’s visit with an old lunar favorite. Easily seen in binoculars, the hexagonal walled plain of Albategnius ap- pears near the terminator about one-third the way north of the south limb. Look north of Albategnius for even larger and more ancient Hipparchus giving an almost “figure 8” view in binoculars. Between Hipparchus and Albategnius to the east are mid-sized craters Halley and Hind. Note the curious ALBATEGNIUS AND HIPPARCHUS ON THE relationship between impact crater Klein on Albategnius’ southwestern wall and TERMINATOR CREDIT: ROGER WARNER that of crater Horrocks on the northeastern wall of Hipparchus. Now let’s power up and “crater hop”... Just northwest of Hipparchus’ wall are the beginnings of the Sinus Medii area. Look for the deep imprint of Seeliger - named for a Dutch astronomer. Due north of Hipparchus is Rhaeticus, and here’s where things really get interesting. If the terminator has progressed far enough, you might spot tiny Blagg and Bruce to its west, the rough location of the Surveyor 4 and Surveyor 6 landing area. -

![Arxiv:1801.08245V2 [Astro-Ph.GA] 14 Feb 2018](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0220/arxiv-1801-08245v2-astro-ph-ga-14-feb-2018-1300220.webp)

Arxiv:1801.08245V2 [Astro-Ph.GA] 14 Feb 2018

Draft version June 21, 2021 Preprint typeset using LATEX style emulateapj v. 12/16/11 THE MASSIVE SURVEY IX: PHOTOMETRIC ANALYSIS OF 35 HIGH MASS EARLY-TYPE GALAXIES WITH HST WFC3/IR1 Charles F. Goullaud Department of Physics, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA; [email protected] Joseph B. Jensen Utah Valley University, Orem, UT, USA John P. Blakeslee Herzberg Astrophysics, Victoria, BC, Canada Chung-Pei Ma Department of Astronomy, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA Jenny E. Greene Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, USA Jens Thomas Max Planck-Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics, Garching, Germany. Draft version June 21, 2021 ABSTRACT We present near-infrared observations of 35 of the most massive early-type galaxies in the local universe. The observations were made using the infrared channel of the Hubble Space Telescope (HST ) Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3) in the F110W (1.1 µm) filter. We measured surface brightness profiles and elliptical isophotal fit parameters from the nuclear regions out to a radius of ∼10 kpc in most cases. We find that 37% (13) of the galaxies in our sample have isophotal position angle rotations greater than 20◦ over the radial range imaged by WFC3/IR, which is often due to the presence of neighbors or multiple nuclei. Most galaxies in our sample are significantly rounder near the center than in the outer regions. This sample contains six fast rotators and 28 slow rotators. We find that all fast rotators are either disky or show no measurable deviation from purely elliptical isophotes. Among slow rotators, significantly disky and boxy galaxies occur with nearly equal frequency. -

X-Ray Luminosities for a Magnitude-Limited Sample of Early-Type Galaxies from the ROSAT All-Sky Survey

Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 302, 209±221 (1999) X-ray luminosities for a magnitude-limited sample of early-type galaxies from the ROSAT All-Sky Survey J. Beuing,1* S. DoÈbereiner,2 H. BoÈhringer2 and R. Bender1 1UniversitaÈts-Sternwarte MuÈnchen, Scheinerstrasse 1, D-81679 MuÈnchen, Germany 2Max-Planck-Institut fuÈr Extraterrestrische Physik, D-85740 Garching bei MuÈnchen, Germany Accepted 1998 August 3. Received 1998 June 1; in original form 1997 December 30 Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article/302/2/209/968033 by guest on 30 September 2021 ABSTRACT For a magnitude-limited optical sample (BT # 13:5 mag) of early-type galaxies, we have derived X-ray luminosities from the ROSATAll-Sky Survey. The results are 101 detections and 192 useful upper limits in the range from 1036 to 1044 erg s1. For most of the galaxies no X-ray data have been available until now. On the basis of this sample with its full sky coverage, we ®nd no galaxy with an unusually low ¯ux from discrete emitters. Below log LB < 9:2L( the X-ray emission is compatible with being entirely due to discrete sources. Above log LB < 11:2L( no galaxy with only discrete emission is found. We further con®rm earlier ®ndings that Lx is strongly correlated with LB. Over the entire data range the slope is found to be 2:23 60:12. We also ®nd a luminosity dependence of this correlation. Below 1 log Lx 40:5 erg s it is consistent with a slope of 1, as expected from discrete emission. -

7.5 X 11.5.Threelines.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-19267-5 - Observing and Cataloguing Nebulae and Star Clusters: From Herschel to Dreyer’s New General Catalogue Wolfgang Steinicke Index More information Name index The dates of birth and death, if available, for all 545 people (astronomers, telescope makers etc.) listed here are given. The data are mainly taken from the standard work Biographischer Index der Astronomie (Dick, Brüggenthies 2005). Some information has been added by the author (this especially concerns living twentieth-century astronomers). Members of the families of Dreyer, Lord Rosse and other astronomers (as mentioned in the text) are not listed. For obituaries see the references; compare also the compilations presented by Newcomb–Engelmann (Kempf 1911), Mädler (1873), Bode (1813) and Rudolf Wolf (1890). Markings: bold = portrait; underline = short biography. Abbe, Cleveland (1838–1916), 222–23, As-Sufi, Abd-al-Rahman (903–986), 164, 183, 229, 256, 271, 295, 338–42, 466 15–16, 167, 441–42, 446, 449–50, 455, 344, 346, 348, 360, 364, 367, 369, 393, Abell, George Ogden (1927–1983), 47, 475, 516 395, 395, 396–404, 406, 410, 415, 248 Austin, Edward P. (1843–1906), 6, 82, 423–24, 436, 441, 446, 448, 450, 455, Abbott, Francis Preserved (1799–1883), 335, 337, 446, 450 458–59, 461–63, 470, 477, 481, 483, 517–19 Auwers, Georg Friedrich Julius Arthur v. 505–11, 513–14, 517, 520, 526, 533, Abney, William (1843–1920), 360 (1838–1915), 7, 10, 12, 14–15, 26–27, 540–42, 548–61 Adams, John Couch (1819–1892), 122, 47, 50–51, 61, 65, 68–69, 88, 92–93, -

The MASSIVE Survey – X

MNRAS 479, 2810–2826 (2018) doi:10.1093/mnras/sty1649 Advance Access publication 2018 June 22 The MASSIVE Survey – X. Misalignment between kinematic and photometric axes and intrinsic shapes of massive early-type galaxies Irina Ene,1,2‹ Chung-Pei Ma,1,2 Melanie Veale,1,2 Jenny E. Greene,3 Jens Thomas,4 5 6,7 8 9 John P. Blakeslee, Caroline Foster, Jonelle L. Walsh, Jennifer Ito and Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article-abstract/479/2/2810/5042947 by Princeton University user on 27 June 2019 Andy D. Goulding3 1Department of Astronomy, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA 2Department of Physics, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA 3Department of Astrophysical Sciences, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544, USA 4Max Plank-Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics, Giessenbachstr. 1, D-85741 Garching, Germany 5Dominion Astrophysical Observatory, NRC Herzberg Astronomy and Astrophysics, Victoria, BC V9E 2E7, Canada 6Sydney Institute for Astronomy, School of Physics A28, The University of Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia 7ARC Centre of Excellence for All Sky Astrophysics in 3 Dimensions (ASTRO 3D), Australia 8George P. and Cynthia Woods Mitchell Institute for Fundamental Physics and Astronomy, and Department of Physics and Astronomy, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843, USA 9Department of Physics, University of California, San Diego, CA 92093, USA Accepted 2018 June 19. Received 2018 June 19; in original form 2018 January 30 ABSTRACT We use spatially resolved two-dimensional stellar velocity maps over a 107 × 107 arcsec2 field of view to investigate the kinematic features of 90 early-type galaxies above stellar mass 1011.5 M in the MASSIVE survey. -

Making a Sky Atlas

Appendix A Making a Sky Atlas Although a number of very advanced sky atlases are now available in print, none is likely to be ideal for any given task. Published atlases will probably have too few or too many guide stars, too few or too many deep-sky objects plotted in them, wrong- size charts, etc. I found that with MegaStar I could design and make, specifically for my survey, a “just right” personalized atlas. My atlas consists of 108 charts, each about twenty square degrees in size, with guide stars down to magnitude 8.9. I used only the northernmost 78 charts, since I observed the sky only down to –35°. On the charts I plotted only the objects I wanted to observe. In addition I made enlargements of small, overcrowded areas (“quad charts”) as well as separate large-scale charts for the Virgo Galaxy Cluster, the latter with guide stars down to magnitude 11.4. I put the charts in plastic sheet protectors in a three-ring binder, taking them out and plac- ing them on my telescope mount’s clipboard as needed. To find an object I would use the 35 mm finder (except in the Virgo Cluster, where I used the 60 mm as the finder) to point the ensemble of telescopes at the indicated spot among the guide stars. If the object was not seen in the 35 mm, as it usually was not, I would then look in the larger telescopes. If the object was not immediately visible even in the primary telescope – a not uncommon occur- rence due to inexact initial pointing – I would then scan around for it. -

Ngc Catalogue Ngc Catalogue

NGC CATALOGUE NGC CATALOGUE 1 NGC CATALOGUE Object # Common Name Type Constellation Magnitude RA Dec NGC 1 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.9 00:07:16 27:42:32 NGC 2 - Galaxy Pegasus 14.2 00:07:17 27:40:43 NGC 3 - Galaxy Pisces 13.3 00:07:17 08:18:05 NGC 4 - Galaxy Pisces 15.8 00:07:24 08:22:26 NGC 5 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.3 00:07:49 35:21:46 NGC 6 NGC 20 Galaxy Andromeda 13.1 00:09:33 33:18:32 NGC 7 - Galaxy Sculptor 13.9 00:08:21 -29:54:59 NGC 8 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:08:45 23:50:19 NGC 9 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.5 00:08:54 23:49:04 NGC 10 - Galaxy Sculptor 12.5 00:08:34 -33:51:28 NGC 11 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.7 00:08:42 37:26:53 NGC 12 - Galaxy Pisces 13.1 00:08:45 04:36:44 NGC 13 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.2 00:08:48 33:25:59 NGC 14 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.1 00:08:46 15:48:57 NGC 15 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.8 00:09:02 21:37:30 NGC 16 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.0 00:09:04 27:43:48 NGC 17 NGC 34 Galaxy Cetus 14.4 00:11:07 -12:06:28 NGC 18 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:09:23 27:43:56 NGC 19 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.3 00:10:41 32:58:58 NGC 20 See NGC 6 Galaxy Andromeda 13.1 00:09:33 33:18:32 NGC 21 NGC 29 Galaxy Andromeda 12.7 00:10:47 33:21:07 NGC 22 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.6 00:09:48 27:49:58 NGC 23 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.0 00:09:53 25:55:26 NGC 24 - Galaxy Sculptor 11.6 00:09:56 -24:57:52 NGC 25 - Galaxy Phoenix 13.0 00:09:59 -57:01:13 NGC 26 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.9 00:10:26 25:49:56 NGC 27 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.5 00:10:33 28:59:49 NGC 28 - Galaxy Phoenix 13.8 00:10:25 -56:59:20 NGC 29 See NGC 21 Galaxy Andromeda 12.7 00:10:47 33:21:07 NGC 30 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:10:51 21:58:39 -

Deep Surface Photometry of Edge-On Spirals in Abell Galaxy Clusters

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. 9281 c ESO 2018 December 11, 2018 Deep surface photometry of edge-on spirals in Abell galaxy clusters: constraining environmental effects B. X. Santiago1 and T. B. Vale1 Instituto de F´ısica, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Av. Bento Gonc¸alves, 9500, CP 15051, Porto Alegre e-mail: [email protected] Received September 15, 1996; accepted March 16, 1997 ABSTRACT Context. There is a clear scarcity of structural parameters for stellar thick discs, especially for spiral galaxies located in high-density regions, such as galaxy clusters and compact groups. Aims. We have modelled the thin and thick discs of 4 edge-on spirals located in Abell clusters: NGC 705, ESO243G49, ESO187G19, LCSBS0496P. Deep I band images of NGC 705 were taken from the HST archive, whereas the remaining images were obtained with the Southern Telescope for Astrophysical Research (SOAR) in Gunn r filter. They reached surface brightness levels of µI ≃ 26.0 mag −2 −2 arcsec and µr ≃ 26.5 mag arcsec , respectively. Methods. Profiles were extracted from the deep images, in directions both parallel and perpendicular to the major axis. Profile fits were carried out at several positions, yielding horizontal and vertical scale parameters for both thin and thick disc components. Results. The extracted profiles and fitted disc parameters vary from galaxy to galaxy. Two galaxies have a horizontal profile with a strong down-turn at outer radii, preventing a simple exponential from fitting the entire range. For the 2 early-type spirals, the thick discs have larger scalelengths than the thin discs, whereas no trend is seen for the later types .