Arxiv:1801.08245V2 [Astro-Ph.GA] 14 Feb 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Local Radio-Galaxy Population at 20

Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 000, 1–?? (2013) Printed 2 December 2013 (MN LATEX style file v2.2) The local radio-galaxy population at 20GHz Elaine M. Sadler1⋆, Ronald D. Ekers2, Elizabeth K. Mahony3, Tom Mauch4,5, Tara Murphy1,6 1Sydney Institute for Astronomy, School of Physics, The University of Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia 2Australia Telescope National Facility, CSIRO, PO Box 76, Epping, NSW 1710, Australia 3ASTRON, the Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy, Postbus 2, 7990 AA, Dwingeloo, The Netherlands 4Oxford Astrophysics, Department of Physics, Keble Road, Oxford OX1 3RH 5SKA Africa, 3rd Floor, The Park, Park Road, Pinelands, 7405, South Africa 6School of Information Technologies, The University of Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia Accepted 0000 December 08. Received 0000 December 08; in original form 0000 December 08 ABSTRACT We have made the first detailed study of the high-frequency radio-source population in the local universe, using a sample of 202 radio sources from the Australia Telescope 20GHz (AT20G) survey identified with galaxies from the 6dF Galaxy Survey (6dFGS). The AT20G- 6dFGS galaxies have a median redshift of z=0.058 and span a wide range in radio luminosity, allowing us to make the first measurement of the local radio luminosity function at 20GHz. Our sample includes some classical FR-1 and FR-2 radio galaxies, but most of the AT20G-6dFGS galaxies host compact (FR-0) radio AGN which appear lack extended radio emission even at lower frequencies. Most of these FR-0 sources show no evidence for rela- tivistic beaming, and the FR-0 class appears to be a mixed population which includes young Compact Steep-Spectrum (CSS) and Gigahertz-Peaked Spectrum (GPS) radio galaxies. -

Molecular Gas in the Elliptical Galaxy NGC 759 Cessfully Reproduce the Observed Properties (Hernquist & Barnes 1991)

A&A manuscript no. (will be inserted by hand later) ASTRONOMY AND Your thesaurus codes are: ASTROPHYSICS 09.13.2; 11.05.1; 11.09.1; 11.09.4; 11.11.1; 6.8.2018 Molecular gas in the elliptical galaxy NGC 759 Interferometric CO observations T. Wiklind1, F. Combes2, C. Henkel3, F. Wyrowski3,4 1 Onsala Space Observatory, S–43992 Onsala, Sweden 2 DEMIRM Observatoire de Paris, 61 Avenue de l’Observatoire, F–75014 Paris, France 3 Max-Planck-Institut f¨ur Radioastronomie, Auf dem H¨ugel 69, D–53121 Bonn, Germany 4 Physikalisches Institut der Universit¨at zu K¨oln, Z¨ulpicher Strasse 77, D–50937 K¨oln, Germany Received date; Accepted date Abstract. We present interferometric observations of CO(1–0) emission in the elliptical galaxy NGC 759 with an angular resolution of 3 ′′. 1 2 ′′. 3 (990 735pc at a distance × × 9 1. Introduction of 66Mpc). NGC759 contains 2.4 10 M⊙ of molecular × gas. Most of the gas is confined to a small circumnuclear Faber & Gallagher (1976) found the apparent absence of ◦ ring with a radius of 650 pc with an inclination of 40 . The an interstellar medium (ISM) in elliptical galaxies surpris- −2 maximum gas surface density in the ring is 750 M⊙ pc . ing since mass loss from evolved stars should contribute as 9 10 Although this value is very high, it is always less than much as 10 10 M⊙ of gas to the ISM during a Hubble or comparable to the critical gas surface density for large time. Today− we know that ellipticals do contain an ISM, scale gravitational instabilities. -

Infrared Spectroscopy of Nearby Radio Active Elliptical Galaxies

The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, 203:14 (11pp), 2012 November doi:10.1088/0067-0049/203/1/14 C 2012. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. INFRARED SPECTROSCOPY OF NEARBY RADIO ACTIVE ELLIPTICAL GALAXIES Jeremy Mould1,2,9, Tristan Reynolds3, Tony Readhead4, David Floyd5, Buell Jannuzi6, Garret Cotter7, Laura Ferrarese8, Keith Matthews4, David Atlee6, and Michael Brown5 1 Centre for Astrophysics and Supercomputing Swinburne University, Hawthorn, Vic 3122, Australia; [email protected] 2 ARC Centre of Excellence for All-sky Astrophysics (CAASTRO) 3 School of Physics, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Vic 3100, Australia 4 Palomar Observatory, California Institute of Technology 249-17, Pasadena, CA 91125 5 School of Physics, Monash University, Clayton, Vic 3800, Australia 6 Steward Observatory, University of Arizona (formerly at NOAO), Tucson, AZ 85719 7 Department of Physics, University of Oxford, Denys, Oxford, Keble Road, OX13RH, UK 8 Herzberg Institute of Astrophysics Herzberg, Saanich Road, Victoria V8X4M6, Canada Received 2012 June 6; accepted 2012 September 26; published 2012 November 1 ABSTRACT In preparation for a study of their circumnuclear gas we have surveyed 60% of a complete sample of elliptical galaxies within 75 Mpc that are radio sources. Some 20% of our nuclear spectra have infrared emission lines, mostly Paschen lines, Brackett γ , and [Fe ii]. We consider the influence of radio power and black hole mass in relation to the spectra. Access to the spectra is provided here as a community resource. Key words: galaxies: elliptical and lenticular, cD – galaxies: nuclei – infrared: general – radio continuum: galaxies ∼ 1. INTRODUCTION 30% of the most massive galaxies are radio continuum sources (e.g., Fabbiano et al. -

V. Spatially-Resolved Stellar Angular Momentum, Velocity Dispersion, and Higher Moments of the 41 Most Massive Local Early-Type Galaxies

MNRAS 000,1{20 (2016) Preprint 9 September 2016 Compiled using MNRAS LATEX style file v3.0 The MASSIVE Survey - V. Spatially-Resolved Stellar Angular Momentum, Velocity Dispersion, and Higher Moments of the 41 Most Massive Local Early-Type Galaxies Melanie Veale,1;2 Chung-Pei Ma,1 Jens Thomas,3 Jenny E. Greene,4 Nicholas J. McConnell,5 Jonelle Walsh,6 Jennifer Ito,1 John P. Blakeslee,5 Ryan Janish2 1Department of Astronomy, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA 2Department of Physics, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA 3Max Plank-Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics, Giessenbachstr. 1, D-85741 Garching, Germany 4Department of Astrophysical Sciences, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544, USA 5Dominion Astrophysical Observatory, NRC Herzberg Institute of Astrophysics, Victoria BC V9E2E7, Canada 6George P. and Cynthia Woods Mitchell Institute for Fundamental Physics and Astronomy, and Department of Physics and Astronomy, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843, USA Accepted XXX. Received YYY; in original form ZZZ ABSTRACT We present spatially-resolved two-dimensional stellar kinematics for the 41 most mas- ∗ 11:8 sive early-type galaxies (MK . −25:7 mag, stellar mass M & 10 M ) of the volume-limited (D < 108 Mpc) MASSIVE survey. For each galaxy, we obtain high- quality spectra in the wavelength range of 3650 to 5850 A˚ from the 246-fiber Mitchell integral-field spectrograph (IFS) at McDonald Observatory, covering a 10700 × 10700 field of view (often reaching 2 to 3 effective radii). We measure the 2-D spatial distri- bution of each galaxy's angular momentum (λ and fast or slow rotator status), velocity dispersion (σ), and higher-order non-Gaussian velocity features (Gauss-Hermite mo- ments h3 to h6). -

Jet-Induced Star Formation in 3C 285 and Minkowski's Object⋆

A&A 574, A34 (2015) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201424932 & c ESO 2015 Astrophysics Jet-induced star formation in 3C 285 and Minkowski’s Object? Q. Salomé, P. Salomé, and F. Combes LERMA, Observatoire de Paris, CNRS UMR 8112, 61 avenue de l’Observatoire, 75014 Paris, France e-mail: [email protected] Received 5 September 2014 / Accepted 6 November 2014 ABSTRACT How efficiently star formation proceeds in galaxies is still an open question. Recent studies suggest that active galactic nucleus (AGN) can regulate the gas accretion and thus slow down star formation (negative feedback). However, evidence of AGN positive feedback has also been observed in a few radio galaxies (e.g. Centaurus A, Minkowski’s Object, 3C 285, and the higher redshift 4C 41.17). Here we present CO observations of 3C 285 and Minkowski’s Object, which are examples of jet-induced star formation. A spot (named 3C 285/09.6 in the present paper) aligned with the 3C 285 radio jet at a projected distance of ∼70 kpc from the galaxy centre shows star formation that is detected in optical emission. Minkowski’s Object is located along the jet of NGC 541 and also shows star formation. Knowing the distribution of molecular gas along the jets is a way to study the physical processes at play in the AGN interaction with the intergalactic medium. We observed CO lines in 3C 285, NGC 541, 3C 285/09.6, and Minkowski’s Object with the IRAM 30 m telescope. In the central galaxies, the spectra present a double-horn profile, typical of a rotation pattern, from which we are able to estimate the molecular gas density profile of the galaxy. -

October 2006

OCTOBER 2 0 0 6 �������������� http://www.universetoday.com �������������� TAMMY PLOTNER WITH JEFF BARBOUR 283 SUNDAY, OCTOBER 1 In 1897, the world’s largest refractor (40”) debuted at the University of Chica- go’s Yerkes Observatory. Also today in 1958, NASA was established by an act of Congress. More? In 1962, the 300-foot radio telescope of the National Ra- dio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) went live at Green Bank, West Virginia. It held place as the world’s second largest radio scope until it collapsed in 1988. Tonight let’s visit with an old lunar favorite. Easily seen in binoculars, the hexagonal walled plain of Albategnius ap- pears near the terminator about one-third the way north of the south limb. Look north of Albategnius for even larger and more ancient Hipparchus giving an almost “figure 8” view in binoculars. Between Hipparchus and Albategnius to the east are mid-sized craters Halley and Hind. Note the curious ALBATEGNIUS AND HIPPARCHUS ON THE relationship between impact crater Klein on Albategnius’ southwestern wall and TERMINATOR CREDIT: ROGER WARNER that of crater Horrocks on the northeastern wall of Hipparchus. Now let’s power up and “crater hop”... Just northwest of Hipparchus’ wall are the beginnings of the Sinus Medii area. Look for the deep imprint of Seeliger - named for a Dutch astronomer. Due north of Hipparchus is Rhaeticus, and here’s where things really get interesting. If the terminator has progressed far enough, you might spot tiny Blagg and Bruce to its west, the rough location of the Surveyor 4 and Surveyor 6 landing area. -

Durham Research Online

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Durham Research Online Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 22 January 2020 Version of attached le: Published Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Babyk, Iu. V. and McNamara, B. R. and Tamhane, P. D. and Nulsen, P. E. J. and Russell, H. R. and Edge, A. C. (2019) 'Origins of molecular clouds in early-type galaxies.', Astrophysical journal., 887 (2). p. 149. Further information on publisher's website: https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/ab54ce Publisher's copyright statement: c 2019. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 http://dro.dur.ac.uk The Astrophysical Journal, 887:149 (17pp), 2019 December 20 https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/ab54ce © 2019. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. -

A Chandra Observation of the X-Ray Environment and Jet of 3C31

Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 000, 000–000 (0000) Printed 2 November 2018 (MN LATEX style file v2.2) A Chandra observation of the X-ray environment and jet of 3C31 M.J. Hardcastle1, D.M. Worrall1, M. Birkinshaw1, R.A. Laing2,3 and A.H. Bridle4 1 Department of Physics, University of Bristol, Tyndall Avenue, Bristol BS8 1TL 2 Space Science and Technology Department, CLRC, Rutherford Appleton Laboratory, Chilton, Didcot, Oxfordshire OX11 0QX 3 University of Oxford, Department of Astrophysics, Nuclear and Astrophysics Laboratory, Keble Road, Oxford OX1 3RH 4 National Radio Astronomy Observatory, 520 Edgemont Road, Charlottesville, VA 22903-2475, U.S.A 2 November 2018 ABSTRACT We have used a deep Chandra observation of the central regions of the twin-jet FRI radio galaxy 3C31 to resolve the thermal X-ray emission in the central few kiloparsecs of the host galaxy, NGC 383, where the jets are thought to be decelerating rapidly. This allows us to make high-precision measurements of the density, temperature and pressure distributions in this region, and to show that the X-ray emitting gas in the centre of the galaxy has a cooling time of only 5 × 107 years. In a companion paper these measurements are used to place constraints on models of the jet dynamics. A previously unknown one-sided X-ray jet in 3C31, extending up to 8 arcsec from the nucleus, is detected and resolved. Its structure and steep X-ray spectrum are similar to those of X-ray jets known in other FRI sources, and we attribute the radiation to synchrotron emission from a high-energy population of electrons. -

An X-Ray View of the Cores of Galaxy Groups

An X-ray view of the cores of galaxy groups Ewan O’Sullivan Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics with credit to Jan Vrtilek & Larry David (C.f.A.) Trevor Ponman & Alastair Sanderson (Uni. of Birmingham) Josh Kempner (Bowdoin College) John Houck (MIT) Groups of Galaxies in the Nearby Universe Santiago, December 2005 X-ray halos of galaxy groups . Many (elliptical dominated) groups have X-ray halos which can contain a large fraction of the baryonic mass of the system. Can be a record of the history of the system (metal enrichment, mergers, cooling in undisturbed systems, etc) . Hot gas halos often used to study total mass profile - probably the best available tool for studying the dark matter content & structure (cosmology, group structure, properties of central galaxy) Groups of Galaxies in the Nearby Universe Santiago, December 2005 X-ray halos of galaxy groups: Questions . Scientific . The central cooling time of this gas is generally short (~108 yr), but we don’t see runaway cooling. What stops it? . Mechanism for metal enrichment of group halos still unclear. Lots of metals in central ellipticals, how do we get them out? . Technical . X-ray mass analysis of groups relies on assumptions of Hydrostatic Equilibrium, relaxed halos, spherical symmetry, etc. In clusters, a disturbed or cooling core can often be excluded because halo is visible to large radius - nearby groups often too faint to allow this. Groups of Galaxies in the Nearby Universe Santiago, December 2005 Sample of X-ray bright groups • 23 Groups from XMM-Newton, 16 -

MASSIVE Galaxies with Supermassive Black Holes

Hubble Space Telescope Cycle 23 GO Proposal 750 Homogeneous Distances and Central Profiles for MASSIVE Survey Galaxies with Supermassive Black Holes Scientific Category: UNRESOLVED STELLAR POPULATIONS AND GALAXY STRUCTURE Scientific Keywords: Black Holes, Cosmological Parameters And Distance Scale, Galaxy Centers, Galaxy Morphology And Structure Instruments: WFC3 Proprietary Period: 12 Proposal Size: Small Orbit Request Prime Parallel Cycle 23 34 0 Abstract Massive early-type galaxies are the subject of intense interest: they exhibit the most massive black holes (BHs), most extreme stellar IMFs, and most dramatic size evolution over cosmic time. Yet, their complex formation histories remain obscure. Enter MASSIVE: a volume-limited survey of the structure and dynamics of the 100 most massive early-type galaxies within ~100 Mpc. We use integral-field spectroscopy (IFS) on sub-arcsecond (with AO) and large scales for simultaneous dynamical modeling of the supermassive BH, stars, and dark matter. The goals of MASSIVE include precise constraints on BH-galaxy scaling relations, the stellar IMF, and late-time assembly of ellipticals. We have already obtained much of the needed IFS and wide-field imaging for this project; here, we propose to add the one missing ingredient: high-resolution imaging with HST. This will nail down the central profiles, greatly reducing the degeneracy between M/L and BH masses in our dynamical orbit modeling. Further, we will measure efficient, high-quality WFC3/IR SBF distances for all targets, thereby removing potentially large errors from peculiar velocities (especially in the high-density regions occupied by massive early-types) or heterogeneous distance methods. Distance errors are insidious: they affect BH masses and galaxy properties in dissimilar ways, and thus can bias both the scatter and slopes of the scaling relations. -

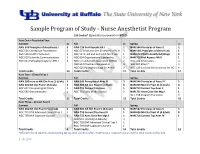

Sample Program of Study

Sample Program of Study - Nurse Anesthetist Program 126 Credits* (Specialty coursework in BOLD) Year One – Preclinical Year Summer Cr Fall Cr Spring Cr NAN 543 Principles of Anesthesia I 3 NAN 718 Prof Aspects NA I 1 NAN 544 Principles of Anes II 2 NGC 501 Conceptual Foundations 3 NGC 527 Eval and Gen Evidence for HC II 3 NAN 544L Principles of Anes II Lab 1 NGC 518 Health Promotion 3 NGC 527L Eval and Gen Evidence II Lab 1 NAN 672 Pharm Anesth/Adj Drugs 3 NGC 520 Scientific Communications 2 NGC 634 Organizational Leadership 3 NAN 719 Prof Aspects NA II 1 NGC 625 Pathophysiology for APN I 3 NGC 575 Adv Helth Assessmnt (CRNA) 2 NGC 502 Informatics 3 NGC 612 Pharmacotherapeutics 4 NGC 509 Ethics* 3 NGC 626 Pathophysiology for APN II 3 NGC 526 Eval and Gen Evidence for HC I 4 Total Credits 14 Total Credits 17 Total Credits 17 Year Two – Clinical Year I Summer Fall Spring NAN 598 Intro to NA Clin Prac (1 d/wk) 2 NAN 545 Principles of Anes III 3 NAN 546 Principles of Anes IV 3 NAN 601 NA Clin Pract I (3 d/wk) 6 NAN 602 NA Clin Pract II (4 d/wk) 8 NAN 603 NA Clin Pract III (4 d/wk) 8 NGC 632 Interpreting HC Policy 3 NAN 711 Current Top Anes 1 NAN 712 Current Top Anes II 1 NGC 692 Grantsmanship 1 NGC 701 State of the Science 3 NAN 721 Anes Crisis Res Mgt I 1 NGC 638 Program Evaluation 3 Total Credits 12 Total Credits 15 Total Credits 16 Year Three – Clinical Year II Summer Fall Spring NAN 604 NA Clin Pract IV (4 d/wk) 6 NAN 605 NA Clin Pract V (4 d/wk) 6 NAN 547 Principles of Anes V 3 NGC 725 DNP Advanced Clinical Prac I 2 NAN 713 Current Top Anes III 1 NAN 606 NA Clin Pract VI (4 d/wk) 8 NGC 798 DNP Capstone Course I 1 NAN 722 Anes Crisis Res Mgt II 1 NAN 714 Current Top Anes IV 1 NGC 533 Teaching in Nursing 3 NGC 726 DNP Advanced Clinical Prac II 2 NGC 799 DNP Capstone Course II 1 Total Credits 9 Total Credits 14 Total Credits 12 *Effective for all students matriculating Spring 2015 and thereafter, N509 is not a required course and the total credits will be 123. -

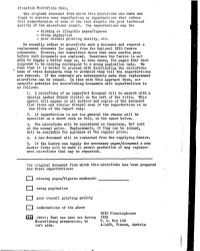

Structure in Radio Galaxies

Atxention Microfiche User, The original document from which this microfiche was made was found to contain some imperfection or imperfections that reduce full comprehension of some of the text despite the good technical quality of the microfiche itself. The imperfections may "be: — missing or illegible pages/figures — wrong pagination — poor overall printing quality, etc. We normally refuse to microfiche such a document and request a replacement document (or pages) from the National INIS Centre concerned. However, our experience shows that many months pass before such documents are replaced. Sometimes the Centre is not able to supply a "better copy or, in some cases, the pages that were supposed to be missing correspond to a wrong pagination only. We feel that it is better to proceed with distributing the microfiche made of these documents than to withhold them till the imperfections are removed. If the removals are subsequestly made then replacement microfiche can be issued. In line with this approach then, our specific practice for microfiching documents with imperfections is as follows: i. A microfiche of an imperfect document will be marked with a special symbol (black circle) on the left of the title. This symbol will appear on all masters and copies of the document (1st fiche and trailer fiches) even if the imperfection is on one fiche of the report only. 2» If imperfection is not too general the reason will be specified on a sheet such as this, in the space below. 3» The microfiche will be considered as temporary, but sold at the normal price. Replacements, if they can be issued, will be available for purchase at the regular price.