A New Zealand Myth: Kupe, Toi And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

APPENDICES 6B Ron's Story

APPENDICES 6b Ron's Story NOTES ON RON'S INTERVIEW Ron and I had had no professional or personal contact prior to my contacting him by telephone to arrange the interview. When I arrived to see Ron, he took me through the building and introduced me to staff and whanau who were there. We shared a cup of tea and some cake before beginning the interview. Ron took the opportunity to gently interview me before I had the chance to interview him. He then introduced himself through his iwi affiliations and background. The interview with Ron was open and emotional at times. Ron made it clear that he had not articulated the basis of his philosophy, theory and practice of counselling as a whole before. He was clearly exploring and developing his own understandings, of himself and his practice of counselling, as we talked. I was interested in what Ron did in his counselling practice and why he did what he did. Ron told me this and frequently also went a step further, attempting to explain what he did and why he did it in terms of accepted Western theories and practices. That is, he drew parallels between his own practice as a Maori counsellor, and established Western practices. It may have been that Ron felt a need to justify his own theory and practice by linking it with recognised and published Western theory and practice of counselling. It may also have been that Ron was formulating his own bicultural models of counselling theory and practice. Alternatively, Ron may have been· better able to articulate Western theory in a cogent and coherent way, while he was still exploring the Maori basis of his practice, 413 6b Ron's Story and often did not have a Maori 'framework' within which to clearly . -

Program Draft.21

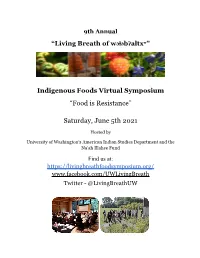

9th Annual “Living Breath of wǝɫǝbʔaltxʷ” Indigenous Foods Virtual Symposium “Food is Resistance” Saturday, June 5th 2021 Hosted by University of Washington’s American Indian Studies Department and the Na’ah Illahee Fund Find us at: https://livingbreathfoodsymposium.org/ www.facebook.com/UWLivingBreath Twitter - @LivingBreathUW Welcome from our Symposium Committee! First, we want to acknowledge and pay respect to the Coast Salish peoples whose traditional territory our event is normally held on at the University of Washington’s wǝɫǝbʔaltxʷ Intellectual House. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, we were unable to come together last year but we are so grateful to be able to reunite this year in a safe virtual format. We appreciate the patience of this community and our presenters’ collective understanding and we are thrilled to be back. We hope to be able to gather in person in 2022. We are also very pleased you can join us today for our 9th annual “Living Breath of wǝɫǝbʔaltxʷ” Indigenous Foods Symposium. This event brings together individuals to share their knowledge and expertise on topics such as Indigenous foodways and ecological knowledge, Tribal food sovereignty and security initiatives, traditional foods/medicines and health/wellness, environmental justice, treaty rights, and climate change. Our planning committee is composed of Indigenous women who represent interdisciplinary academic fields of study and philanthropy and we volunteer our time to host this annual symposium. We are committed to Indigenous food, environmental, and social justice and recognize the need to maintain a community-based event as we all carry on this important work. We host this event and will continue to utilize future symposia to better serve our Indigenous communities as we continue to foster dialogue and build collaborative networks to sustain our cultural food practices and preserve our healthy relationships with the land, water, and all living things. -

Te Runanga 0 Ngai Tahu Traditional Role of the Rona!Sa

:I: Mouru Pasco Maaka, who told him he was the last Maaka. In reply ::I: William told Aritaku that he had an unmerried sister Ani, m (nee Haberfield, also Metzger) in Murihiku. Ani and Aritaku met and went on to marry. m They established themselves in the area of Waimarama -0 and went on to have many children. -a o Mouru attended Greenhills Primary School and o ::D then moved on to Southland Girls' High School. She ::D showed academic ability and wanted to be a journalist, o but eventually ended up developing photographs. The o -a advantage of that was that today we have heaps of -a beautiful photos of our tlpuna which we regard as o priceless taolsa. o ::D Mouru went on to marry Nicholas James Metzger ::D in 1932. Nick's grandfather was German but was o educated in England before coming to New Zealand. o » Their first son, Nicholas Graham "Tiny" was born the year » they were married. Another child did not follow until 1943. -I , around home and relished the responsibility. She Mouru had had her hopes pinned on a dainty little girl 2S attended Raetihi School and later was a boarder at but instead she gave birth to a 13lb 40z boy called Gary " James. Turakina Maori Girls' College in Marton. She learnt the teachings of both the Ratana and Methodist churches. Mouru went to her family's tlU island Pikomamaku In 1944 Ruruhira took up a position at Te Rahui nui almost every season of her life. She excelled at Wahine Methodist Hostel for Maori girls in Hamilton cooking - the priest at her funeral remarked that "she founded by Princess Te Puea Herangi. -

Ngāti Hāmua Environmental Education Sheets

NGTI HMUA ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION SHEETS Produced by Rangitne o Wairarapa Inc in conjunction with Greater Wellington 2006 2 NGTI HMUA ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION SHEETS This education resource provides the reader with information about the environment from the perspective of the Ngti Hmua hap of Rangitne o Wairarapa iwi. There are 9 separate sheets with each one focussing on a different aspect of Mori customary belief. The first two sheets look at history relating to Ngti Hmua starting with the creation myth and the Maori gods (Nga Atua). The second sheet (Tupuna) looks at the Ngti Hmua ancestors that have some link to the Wairarapa including Maui – who fished up Aotearoa, Kupe – the first explorer to these shores, Whtonga aboard the Kurahaup waka and his descendants. The remaining sheets describe the values, practices or uses that Ngti Hmua applied to their environment in the Wairarapa valleys, plains, mountains, waterways and coastal areas. The recording of this information was undertaken so that people from all backgrounds can gain an appreciation of the awareness that the kaumtua of Ngti Hmua have of the natural world. Rangitne o Wairarapa and Greater Wellington Regional Council are pleased to present this information to the people of the Wairarapa and beyond. This resource was created as part of the regional council’s iwi project funding which helps iwi to engage in environmental matters. For further information please contact Rangitne o Wairarapa Runanga 06 370 0600 or Greater Wellington 06 378 2484 Na reira Nga mihi nui ki a koutou katoa 3 CONTENTS Page SHEET 1 Nga Atua –The Gods 4 2 Nga Tupuna – The Ancestors 8 3 Te Whenua – The Land 14 4 Nga Maunga – The Mountains 17 5 Te Moana – The Ocean 19 6 Nga Mokopuna o Tnemahuta – Flora 22 7 Nga Mokopuna o Tnemahuta – Fauna 29 8 Wai Tapu – Waterways 33 9 Kawa – Protocols 35 4 Ngti Hmua Environmental Education series - SHEET 1 of 9 NGA ATUA - THE GODS Introduction The Cosmic Genealogy The part that the gods play in the life of all M ori is hugely s ignificant. -

Portrayals of the Moriori People

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. i Portrayals of the Moriori People Historical, Ethnographical, Anthropological and Popular sources, c. 1791- 1989 By Read Wheeler A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History, Massey University, 2016 ii Abstract Michael King’s 1989 book, Moriori: A People Rediscovered, still stands as the definitive work on the Moriori, the Native people of the Chatham Islands. King wrote, ‘Nobody in New Zealand – and few elsewhere in the world- has been subjected to group slander as intense and as damaging as that heaped upon the Moriori.’ Since its publication, historians have denigrated earlier works dealing with the Moriori, arguing that the way in which they portrayed Moriori was almost entirely unfavourable. This thesis tests this conclusion. It explores the perspectives of European visitors to the Chatham Islands from 1791 to 1989, when King published Moriori. It does this through an examination of newspapers, Native Land Court minutes, and the writings of missionaries, settlers, and ethnographers. The thesis asks whether or not historians have been selective in their approach to the sources, or if, perhaps, they have ignored the intricacies that may have informed the views of early observers. The thesis argues that during the nineteenth century both Maori and European perspectives influenced the way in which Moriori were portrayed in European narrative. -

The Ngati Awa Raupatu Report

THE NGATI AWA RAUPATU REPORT THE NGAT I AWA RAUPATU REPORT WA I 46 WAITANGI TRIBUNAL REPORT 1999 The cover design by Cliä Whiting invokes the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi and the consequent interwoven development of Maori and Pakeha history in New Zealand as it continuously unfolds in a pattern not yet completely known A Waitangi Tribunal report isbn 1-86956-252-6 © Waitangi Tribunal 1999 Edited and produced by the Waitangi Tribunal Published by Legislation Direct, Wellington, New Zealand Printed by PrintLink, Wellington, New Zealand Text set in Adobe Minion Multiple Master Captions set in Adobe Cronos Multiple Master LIST OF CONTENTS Letter of transmittal. ix Chapter 1Chapter 1: ScopeScopeScope. 1 1.1 Introduction. 1 1.2 The raupatu claims . 2 1.3 Tribal overlaps . 3 1.4 Summary of main åndings . 4 1.5 Claims not covered in this report . 10 1.6 Hearings. 10 Chapter 2: Introduction to the Tribes. 13 2.1 Ngati Awa and Tuwharetoa . 13 2.2 Origins of Ngati Awa . 14 2.3 Ngati Awa today . 16 2.4 Origins of Tuwharetoa. 19 2.5 Tuwharetoa today . .20 2.6 Ngati Makino . 22 Chapter 3: Background . 23 3.1 Musket wars. 23 3.2 Traders . 24 3.3 Missionaries . 24 3.4 The signing of the Treaty of Waitangi . 25 3.5 Law . 26 3.6 Principles of the Treaty of Waitangi. 28 Chapter 4: The Central North Island Wars . 33 4.1 The relevance of the wars to Ngati Awa. 33 4.2 Conclusion . 39 Chapter 5: The Völkner And Fulloon Slayings . -

(Māori) Battalion

Fact sheet 5: The formation of the 28th (Māori) Battalion When the decision was made in October 1939 to form a Māori military unit one suggestion was to call it the ‘Treaty of Waitangi’ battalion. It was felt that this would draw the attention of both Māori and Pākehā to their respective obligations under the Treaty. Article Three of the Treaty spoke of the rights and obligations of British subjects, something Āpirana Ngata saw as ‘the price of citizenship’. He believed that if Māori were to have a say in shaping the future of the nation after the war, they needed to participate fully during it. It was also a matter of pride. As Ngata asked, ‘how can we ever hold up our heads, when the struggle is over, to the question, “Where were you when New Zealand was at war?”’ Officially called the New Zealand 28th (Māori) Battalion, the unit was part of the 2nd New Zealand Division, the fighting arm of the 2nd New Zealand Expeditionary Force (2NZEF). The NZ Division was made up of 15,000- 20,000 men, divided into three infantry brigades (the 4th, 5th and 6th Brigades) plus artillery, engineers, signals, medical and service units. Each brigade initially had three infantry battalions (numbered from 18th to 26th). The 28th (Māori) Battalion was at times attached to each of the Division's three brigades. Each battalion was commanded by a lieutenant-colonel. The Māori Battalion usually contained 700-750 men, divided into five companies. The Māori Battalion’s four rifle companies were organised on a tribal basis: • A Company was based on recruits from -

Kupe Press Release

MEDIA RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Image Credit: Pä-kanae (fish trap), Hokianga, Northland. Photograph by Michael Hall Kupe Sites Ngä tapuwae o Kupe Landmarks of the great voyager An exhibition developed by Te Papa that Wairarapa, the Wellington region, and the top of celebrates a great Polynesian voyager’s the South Island. connections with New Zealand opens at Whangarei Art Museum on 11th June. Kupe is The exhibition has its origin in research regarded by many iwi (tribes) as the ancestor who undertaken for the exhibition Voyagers: discovered this country. Kupe Sites, a touring Discovering the Pacific at Te Papa in 2002. Kupe exhibition from the Museum of New Zealand Te was one of four notable Pacific voyagers whose Papa Tongarewa, explores the stories of Kupe’s achievements were celebrated in that exhibition. encounter with New Zealand through names of Te Papa researchers, along with photographer various landmarks and places and even the name Michael Hall, visited the four areas and worked Aotearoa. with iwi there to capture this powerful images. Some iwi tell the story of Kupe setting out from Kupe Sites offers visitors a unique encounter with his homeland Hawaiki in pursuit of Te Wheke-a- New Zealand’s past and reveals the significance of Muturangi, a giant octopus. Others recount how landscape and memory in portraying a key figure Kupe, in love with his nephew’s wife, took her in the country’s history. husband fishing, left him out at sea to drown, then fled from the family’s vengeance. The exhibition runs until 27th August, 2018. -

And Taewa Māori (Solanum Tuberosum) to Aotearoa/New Zealand

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Traditional Knowledge Systems and Crops: Case Studies on the Introduction of Kūmara (Ipomoea batatas) and Taewa Māori (Solanum tuberosum) to Aotearoa/New Zealand A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Master of AgriScience in Horticultural Science at Massey University, Manawatū, New Zealand Rodrigo Estrada de la Cerda 2015 Kūmara and Taewa Māori, Ōhakea, New Zealand i Abstract Kūmara (Ipomoea batatas) and taewa Māori, or Māori potato (Solanum tuberosum), are arguably the most important Māori traditional crops. Over many centuries, Māori have developed a very intimate relationship to kūmara, and later with taewa, in order to ensure the survival of their people. There are extensive examples of traditional knowledge aligned to kūmara and taewa that strengthen the relationship to the people and acknowledge that relationship as central to the human and crop dispersal from different locations, eventually to Aotearoa / New Zealand. This project looked at the diverse knowledge systems that exist relative to the relationship of Māori to these two food crops; kūmara and taewa. A mixed methodology was applied and information gained from diverse sources including scientific publications, literature in Spanish and English, and Andean, Pacific and Māori traditional knowledge. The evidence on the introduction of kūmara to Aotearoa/New Zealand by Māori is indisputable. Mātauranga Māori confirms the association of kūmara as important cargo for the tribes involved, even detailing the purpose for some of the voyages. -

And Did She Cry in Māori?”

“ ... AND DID SHE CRY IN MĀORI?” RECOVERING, REASSEMBLING AND RESTORYING TAINUI ANCESTRESSES IN AOTEAROA NEW ZEALAND Diane Gordon-Burns Tainui Waka—Waikato Iwi A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History The University of Canterbury 2014 Preface Waikato taniwha rau, he piko he taniwha he piko he taniwha Waikato River, the ancestral river of Waikato iwi, imbued with its own mauri and life force through its sheer length and breadth, signifies the strength and power of Tainui people. The above proverb establishes the rights and authority of Tainui iwi to its history and future. Translated as “Waikato of a hundred chiefs, at every bend a chief, at every bend a chief”, it tells of the magnitude of the significant peoples on every bend of its great banks.1 Many of those peoples include Tainui women whose stories of leadership, strength, status and connection with the Waikato River have been diminished or written out of the histories that we currently hold of Tainui. Instead, Tainui men have often been valorised and their roles inflated at the expense of Tainui women, who have been politically, socially, sexually, and economically downplayed. In this study therefore I honour the traditional oral knowledges of a small selection of our tīpuna whaea. I make connections with Tainui born women and those women who married into Tainui. The recognition of traditional oral knowledges is important because without those histories, remembrances and reconnections of our pasts, the strengths and identities which are Tainui women will be lost. Stereotypical male narrative has enforced a female passivity where women’s strengths and importance have become lesser known. -

Rangi Above/Papa Below, Tangaroa Ascendant, Water All Around Us: Austronesian Creation Myths

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-2005 Rangi above/Papa below, Tangaroa ascendant, water all around us: Austronesian creation myths Amy M Green University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Green, Amy M, "Rangi above/Papa below, Tangaroa ascendant, water all around us: Austronesian creation myths" (2005). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 1938. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/b2px-g53a This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RANGI ABOVE/ PAPA BELOW, TANGAROA ASCENDANT, WATER ALL AROUND US: AUSTRONESIAN CREATION MYTHS By Amy M. Green Bachelor of Arts University of Nevada, Las Vegas 2004 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in English Department of English College of Liberal Arts Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas May 2006 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 1436751 Copyright 2006 by Green, Amy M. -

Hawaiki Cable Project Presentation

South Pacific region specificity L.os Angeles Hawaii q Huge distances Hawaii q Limited populaons Guam Kiribati Nauru q Isolaon issues Tuvalu Tokelau Papua New Guinea Solomon Wallis Samo a American Samoa q Need for cheaper Vanuatu French Polynesia and faster bandwidth New CaledoniaFiji Niue Tong Cook Island a q Satellite bandwidth Norfolk Sydney price over 1500 USD / Mbps Auckland 2 Existing systems in South Pacific region q Southern Cross : Sydney - Auckland - Hawaii - US west coast - Suva - Sydney ü Capacity: 6 Tb/s ü End of life: 2020 q Endeavour (Telstra) : Sydney - Hawaii HawaiiHawaii ü Capacity: 1,2 Tb/s ü End of life: 2034 Guam q Gondwana : Nouméa - Sydney ü Capacity: 640 Gb/s Madang Honiara Apia ü End of life: 2033 Wallis Port Vila Pago Pago Tahiti Suva q Honotua : Tahi - Hawaii Noumea Nuku’alofa ü Capacity: 640 Gb/s Norfolk Is. ü End of life: 2035 Sydney Auckland q ASH : Pago-Pago - Hawaii ü Capacity: 1 Gb/s ü End of life: 2014 / 2015 ? (no more spare parts) ü SAS cable : Apia - Pago Pago 3 Hawaiki cable project overview q Project summary ü Provide internaonal bandwidth to Australia + New Zealand + Pacific Islands ü Propose point to point capacity via 100 Gb/s wavelengths ü System design capacity : 20 Tbps ü 2 step project q Time schedule ü Q1 2013 : signature of supplier contract ü Service date : 2015 q Project development by Intelia (www.intelia.nc) ü Leading telecom integrator ü Partnership with Ericsson, ZTE, Telstra, Prysmian, etc… ü 2011 turnover > USD 40M Commercial references : ü Supply and installaon of 3G+ mobile network in NC ü IP transit service for Gondwana cable in Sydney Submarine cable experience - in partnership with ASN: ü New Caledonia cable : Gondwana in 2008 - 2 100 km ü French Polynesia cable : Honotua in 2010 - 4 500 km 4 Hawaiki Cable Step 1 Main backbone / Strategic route Hawaii California Hawaii Guam Madang Honiara Pago Pago Wallis Apia Tahiti Port Vila Suva Noumea Niue Nuku’alofa Rarotonga Norfolk Is.