ANGKOR Exploring Cambodia's Sacred City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Along the Royal Roads to Angkor

Chapter Four The Royal Roads of King Jayavarman VII and its Architectural Remains 4.1 King Jayavarman VII’s Royal Roads 4.1.1 General Information Jayavarman VII’s Royal Roads was believed (by many scholars) to be built in the era of Jayavarman VII who ruled Khmer empire between AD 1812 – 1218. The road network not only cover the area of the modern-day Cambodia but also the large areas of the present Laos, Thailand and Vietnam that were under the control of the empire as well. As demonstrated by Ooi Keat Gin in Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopeida from Angkor Wat to East Timor Volume Two; highways were built—straight, stone-paved roads running across hundreds of kilometers, raised above the flood level, with stone bridges across rivers and lined with rest houses every 15 kilometers. Parts of some roads are still visible, even serving as the bed for modern roads. From the capital city, Angkor, there were at least two roads to the east and two to the west. One of the latter ran across the Dangrek Mountains to Phimai and another went due west toward Sisophon, which means toward the only lowland pass from Cambodia into eastern Thailand in the direction of Lopburi or Ayutthaya. Toward the east, one road has been traced almost to the Mekong, and according to an inscription in which these roads are described, it may continue as far as the capital of Champa1 1 Ooi. (2004). Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopeida from Angkor Wat to East Timor Volume Two, (California: ABC-CLIO.inc.) pg. -

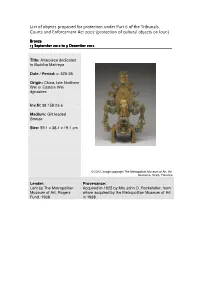

List of Objects Proposed for Protection Under Part 6 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (Protection of Cultural Objects on Loan)

List of objects proposed for protection under Part 6 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (protection of cultural objects on loan) Bronze 15 September 2012 to 9 December 2012 Title: Altarpiece dedicated to Buddha Maitreya Date / Period: c. 525-35 Origin: China, late Northern Wei or Eastern Wei dynasties Inv.N: 38.158.2a-e Medium: Gilt leaded Bronze Size: 59.1 x 38.1 x 19.1 cm © 2012. Image copyright The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Art Resource, Scala, Florence Lender: Provenance: Lent by The Metropolitan Acquired in 1925 by Mrs John D. Rockefeller, from Museum of Art, Rogers whom acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art Fund, 1938 in 1938. List of objects proposed for protection under Part 6 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (protection of cultural objects on loan) Bronze 15 September 2012 to 9 December 2012 Title: Apollo Fountain Date / Period: 1532 Artist: Peter Flötner Inv.N: PL 1206/PL 0024 Medium: Brass Size: H. Incl. Base: 100 cm Base: 55 x 55 cm Museen der Stadt Nürnberg, Gemälde- und Skulpturensammlung Lender: Provenance: Leihgabe der Museen der Commissioned by the archers’ company for their Stadt Nürnberg, Gemälde- shooting yard, Herrenschiesshaus am Sand, und Skulpturensammlung Nuremberg; courtyard of the Pellerhaus. City Museum Fembohaus, Nuremberg (on permanent loan from the city of Nuremberg). List of objects proposed for protection under Part 6 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (protection of cultural objects on loan) Bronze 15 September 2012 to 9 December 2012 Title: Avalokiteshvara Date / Period: 9th- 10th century Origin: Java Inv.N: 509 Medium: Silvered Bronze Size: sculpture: 101 x 49 x 28 cm Base: 140 x 47 cm Weight: 250-300kgs Jakarta, Museum Nasional Indonesia Collection/Photo Feri Latief Lender: Provenance: National Museum Discovered in Tekaran, in Surakarta, Indonesia Indonesia (Philip Rawson, The Art of Southeast Asia, London, 1967, pp. -

Claiming the Hydraulic Network of Angkor with Viṣṇu

Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 9 (2016) 275–292 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jasrep Claiming the hydraulic network of Angkor with Viṣṇu: A multidisciplinary approach including the analysis of archaeological remains, digital modelling and radiocarbon dating: With evidence for a 12th century renovation of the West Mebon Marnie Feneley a,⁎, Dan Penny b, Roland Fletcher b a University of Sydney and currently at University of NSW, Australia b University of Sydney, Australia article info abstract Article history: Prior to the investigations in 2004–2005 of the West Mebon and subsequent analysis of archaeological material in Received 23 April 2016 2015 it was presumed that the Mebon was built in the mid-11th century and consecrated only once. New data Received in revised form 8 June 2016 indicates a possible re-use of the water shrine and a refurbishment and reconsecration in the early 12th century, Accepted 14 June 2016 at which time a large sculpture of Viṣṇu was installed. Understanding the context of the West Mebon is vital to Available online 11 August 2016 understanding the complex hydraulic network of Angkor, which plays a crucial role in the history of the Empire. Keywords: © 2016 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license Archaeology (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). Angkor Digital visualisation 3D max Hydraulic network Bronze sculpture Viṣṇu West Mebon 14C dates Angkor Wat Contents 1. Introduction.............................................................. 276 2. The West Mebon — background.................................................... -

Temples Tour Final Lite

explore the ancient city of angkor Visiting the Angkor temples is of course a must. Whether you choose a Grand Circle tour or a lessdemanding visit, you will be treated to an unforgettable opportunity to witness the wonders of ancient Cambodian art and culture and to ponder the reasons for the rise and fall of this great Southeast Asian civili- zation. We have carefully created twelve itinearies to explore the wonders of Siem Reap Province including the must-do and also less famous but yet fascinating monuments and sites. + See the interactive map online : http://angkor.com.kh/ interactive-map/ 1. small circuit TOUR The “small tour” is a circuit to see the major tem- ples of the Ancient City of Angkor such as Angkor Wat, Ta Prohm and Bayon. We recommend you to be escorted by a tour guide to discover the story of this mysterious and fascinating civilization. For the most courageous, you can wake up early (depar- ture at 4:45am from the hotel) to see the sunrise. (It worth it!) Monuments & sites to visit MORNING: Prasats Kravan, Banteay Kdei, Ta Prohm, Takeo AFTERNOON: Prasats Elephant and Leper King Ter- race, Baphuon, Bayon, Angkor Thom South Gate, Angkor Wat Angkor Wat Banteay Srei 2. Grand circuit TOUR 3. phnom kulen The “grand tour” is also a circuit in the main Angkor The Phnom Kulen mountain range is located 48 km area but you will see further temples like Preah northwards from Angkor Wat. Its name means Khan, Preah Neak Pean to the Eastern Mebon and ‘mountain of the lychees’. -

Views of Angkor in French Colonial Cambodia (1863-1954)

“DISCOVERING” CAMBODIA: VIEWS OF ANGKOR IN FRENCH COLONIAL CAMBODIA (1863-1954) A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Jennifer Lee Foley January 2006 © 2006 Jennifer Lee Foley “DISCOVERING” CAMBODIA: VIEWS OF ANGKOR IN FRENCH COLONIAL CAMBODIA (1863-1954) Jennifer Lee Foley, Ph. D Cornell University 2006 This dissertation is an examination of descriptions, writings, and photographic and architectural reproductions of Angkor in Europe and the United States during Cambodia’s colonial period, which began in 1863 and lasted until 1953. Using the work of Mary Louise Pratt on colonial era narratives and Mieke Bal on the construction of narratives in museum exhibitions, this examination focuses on the narrative that came to represent Cambodia in Europe and the United States, and is conducted with an eye on what these works expose about their Western, and predominately French, producers. Angkor captured the imagination of readers in France even before the colonial period in Cambodia had officially begun. The posthumously published journals of the naturalist Henri Mouhot brought to the minds of many visions of lost civilizations disintegrating in the jungle. This initial view of Angkor proved to be surprisingly resilient, surviving not only throughout the colonial period, but even to the present day. This dissertation seeks to follow the evolution of the conflation of Cambodia and Angkor in the French “narrative” of Cambodia, from the initial exposures, such as Mouhot’s writing, through the close of colonial period. In addition, this dissertation will examine the resilience of this vision of Cambodia in the continued production of this narrative, to the exclusion of the numerous changes that were taking place in the country. -

Part 3. Discussion Chapter 1

Part 3. Discussion Chapter 1. The Ceramics Unearthed from Longvek and Krang Kor Yuni Sato Department of Planning and Coordination, Nara National Research Institute for Cultural Properties 1. Introduction Conventionally, archeological studies of Cambodia focused mainly on the prehistoric times and the Angkor period, and the post-Angkor period were virtually ignored. This “post-Angkor period” points to the approximately 430-year timeframe be- tween the fall of Angkor in 1431 until 1863 when the French colonial rule began. These 430 years had been cloaked in mystery for a long time. In has only been in recent years that first steps in archeological research of the said period was started mainly by the Nara National Research Institute for Cultural Properties (Nara 2008). Research was conducted at Longvek, the royal capital of the post-Angkor period, and Krang Kor, a site at which burials was discovered, and many artifacts were excavated there. The unearthed artifacts serve an important role in explaining Cambodia during the post-Angkor period. This chapter will look back on the ceramics, which were excavated at both of the sites, and discuss their characteristics and significance. 2. Ceramics Excavated at the Krang Kor Site As explained in Part 1, the archaeological research of the Krang Kor site can be considered an important case, as two burials were discovered in good condition and a large volume of assemblage that are highly likely connected with each other had been excavated. Of imported ceramics, Si Satchanalai celadon, Chinese celadon, and Jingdezhen blue and white porcelain were all given the general dates of mid-15th century to early 16th century (Chart 1). -

The Library of the Musée National Des Arts Asiatiques Guimet (National Museum of Asian Arts, Paris, France)

Submitted on: June 1, 2013 Museum library and intercultural networking : the library of the Musée national des arts asiatiques Guimet (National Museum of Asian Arts, Paris, France) Cristina Cramerotti Library and archives department, Musée national des arts asiatiques Guimet, Paris, France [email protected] Copyright © 2013 by Cristina Cramerotti. This work is made available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ Abstract: The Library and archives department of the musée Guimet possess a wide array of collections: besides books and periodicals, it houses manuscripts, scientific archives – both public and privates, photographic archives and sound archives. From the beginning in 1889, the library is at the core of research and communications with scholars, museums, and various cultural institutions all around the world, especially China, Japan, Korea and Taiwan. We exchange exhibition catalogues and publications dealing with the museum collections, engage in joint editions of its most valuable manuscripts (with China), bilingual editions of historical documents (French and Japanese) and joint databases of photographs (with Japan). Every exhibition, edition or database project requires the cooperation of the two parties, a curator of musée Guimet and a counterpart from the institution we deal with. The exchange is twofold and mutually enriching. Since some years we are engaged in various national databases in order to highlight our collection: a collective library catalogue, the French photographic platform Arago, and of course Joconde, central database maintained by the Ministry of culture which documents the collections of the main French museums. Other databases are available on our website in cooperation with Réunion des musées nationaux, a virtual exposition on early Meiji Japan, and a database of Chinese ceramics. -

![Bibliography [PDF] (97.67Kb)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4717/bibliography-pdf-97-67kb-824717.webp)

Bibliography [PDF] (97.67Kb)

WORKS CITED Atlas Colonial illustré Paris: Librarie Larousse, 1905. Bal, Mieke. Double Exposures The Subject of Cultural Analysis. New York: Routledge, 1996. Benjamin, Walter. “The Task of the Translator,” Illuminations Essays and Reflections New York: Schocken Books, 1969. Benoit, Pierre. Le Roi Lépreux. Paris: Kailash Éditions, 2000. Bingham, Robert. Lightening on the Sun. New York: Doubleday, 2000. Black, Jeremy. The British Abroad the Grand Tour in the Eighteenth Century. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1992. Bouillevaux, C. E. Ma visite aux ruines cambodgiennes en 1850 Sanit-Quentin: Imprimerie J. Monceau, 1874. ———. Voyage Dans L'indo-Chine 1848-1856. Paris: Librarie de Victor Palmé, 1858. Carné, Louis de. Travels on the Mekong : Cambodia, Laos and Yunnan, the Political and Trade Report of the Mekong Exploration Commission (June 1866-June 1868). Bangkok: White Lotus, 2000. David Chandler, “An Anti-Vietnamese Rebellion in Early Nineteenth Century Cambodia”, Facing the Cambodian Past, Bangkok, Silkworm Books, 1996b. ———. "Assassination of Résident Bardez." In Facing the Cambodian Past: Selected Essays 1971-1994. Chiang Mai: Silkworm, 1996b. ———. "Cambodian Royal Chronicles (Rajabangsavatar), 1927-1949: Kingship and Historiography at the End of the Colonial Era." In Facing the Cambodian Past : Selected Essays 1971-1994, vi, [1], 331. Chiang Mai: Silkworn Books, 1996b. ———. A History of Cambodia. Second ed. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books, 1996a. ———. "Seeing Red: Perceptions of Cambodian History in Democratic Kampuchea." In Facing the Cambodian Past Selected Essays 1971-1994. Chiang mai: Silkworm Books, 1996b. 216 217 ———. "Transformation in Cambodia." In Facing the Cambodian Past Selected Essays 1971-1994. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books, 1996b. Chimprabha, Marisa. "Anti-Thai Feelings Flare up in Cambodia." The Nation, May 10 2004. -

Gods of Angkor: Bronzes from the National Museum of Cambodia

Page 1 OBJECT LIST Gods of Angkor: Bronzes from the National Museum of Cambodia At the J. Paul Getty Museum, Getty Center February 22 — August 14, 2011 1. Maitreya 3. Buddha Cambodia, Angkor period, early Cambodia, pre Angkor period, 10th century second half of 7th century Bronze; 75.5 x 50 x 23 cm (29 3/4 x Bronze; figure and base, 39 x 11.5 x 19 11/16 x 9 1/16 in.) 10.5 cm (15 3/8 x 4 1/2 x 4 1/8 in.) Provenance: Kampong Chhnang Provenance: Kampong Cham province, Wat Ampil Tuek; acquired province, Cheung Prey district, 21 September 1926; transferred Sdaeung Chey village; acquired from Royal Library, Phnom Penh 2006 National Museum of Cambodia, National Museum of Cambodia, Phnom Penh, Ga2024 Phnom Penh, Ga6937 2. Buddha 4. Buddha Cambodia, pre Angkor period, 7th Cambodia, pre Angkor period, century second half of 7th century Bronze; 49 x 16 x 10 cm (19 5/16 x Bronze; 14 x 5 x 3 cm (5 1/2 x 1 6 5/16 x 3 15/16 in.) 15/16 x 1 3/16 in.) Provenance: Kampong Chhnang Provenance: Kampong Cham province, Kampong Leaeng district, province, Cheung Prey district, Sangkat Da; acquired 11 March Sdaeung Chey village; acquired 1967 2006 National Museum of Cambodia, National Museum of Cambodia, Phnom Penh, Ga5406 Phnom Penh, Ga6938 -more- -more- Page 2 5. Buddha 9. Vajra bearing Guardian Cambodia, pre Angkor period, China, Sui or Tang dynasty, late 6th second half of 7th century 7th century Bronze; figure and base, 25 x 8 x 5 Bronze with traces of gilding; 15 x 6 cm (9 13/16 x 3 1/8 x 1 15/16 in.) x 3 cm (5 7/8 x 2 3/8 x 1 3/16 in.) Provenance: Kampong Cham Provenance: Kampong Cham province, Cheung Prey district, province, Cheung Prey district, Sdaeung Chey village; acquired Sdaeung Chey village; acquired 2006 2006 National Museum of Cambodia, National Museum of Cambodia, Phnom Penh, Ga6939 Phnom Penh, Ga6943 6. -

Angkor Highlight (04 Nights / 05 Days)

(Approved By Ministry of Tourism, Govt. of India) Angkor Highlight (04 Nights / 05 Days) Routing: Arrival Siem Reap - Rolous Group – Small Circuit – Angkor Wat – Grand Circuit - Banteay Srei – Tonle Sap Lake - Siem Reap Day 01 : Arrival Siem Reap (D) Welcome to Siem Reap, Cambodia! Upon arrival at Siem Reap Airport, greeting by our friendly tour guide, then you will be transferred direct to check in at hotel (room may ready at noon). This afternoon, we drive to visit the Angkor National Museum, learn about “the Legend Revealed” and see how the Khmer Empire has been established during the golden period. Continue to visit the Killing Fields at Wat Thmey, get to know some information about Khmer Rouge Regime or called the year of Zero (1975 – 1979) where over 2 million of Khmer people has been killed. Next visit to Preah Ang Check Preah Angkor, the secret place where local people go praying for good luck or safe journey. Day 02 : Rolous Group – Small Circuit (B, L) In the morning – we drive to explore the Roluos group. The Roluos group lies 15km(10 miles) southwest of Siem Reap and includes three temples - Bakong, Prah Ko and Lolei - dating from the late 9th century and corresponding to the ancient capital of Hariharalaya, from which the name of Lolei is derived. Remains include 3 well-preserved early temples that venerated the Hindu gods. The bas-reliefs are some of the earliest surviving examples of Khmer art. Modern-day villages surround the temples. In the afternoon, we visit small circuit including the unique brick sculptures of Prasat Kravan, the jungle intertwined Ta Prohm, made famous in Angelina Jolie’s Tomb Raider movie. -

Post/Colonial Discourses on the Cambodian Court Dance

Kyoto University Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 42, No. 4, 東南アジア研究 March 2005 42巻 4 号 Post/colonial Discourses on the Cambodian Court Dance SASAGAWA Hideo* Abstract Under the reign of King Ang Duong in the middle of nineteenth century, Cambodia was under the influence of Siamese culture. Although Cambodia was colonized by France in 1863, the royal troupe of the dance still performed Siamese repertoires. It was not until the cession of the Angkor monuments from Siam in 1907 that Angkor began to play a central role in French colonial discourse. George Groslier’s works inter alia were instrumental in historicizing the court dance as a “tradition” handed down from the Angkorean era. Groslier appealed to the colonial authorities for the protection of this “tradition” which had allegedly been on the “decline” owing to the influence of French culture. In the latter half of the 1920s the Résident Supérieur au Cambodge temporarily succeeded in transferring the royal troupe to Groslier’s control. In the 1930s members of the royal family set out to reconstruct the troupe, and the Minister of Palace named Thiounn wrote a book in which he described the court dance as Angkorean “tradition.” His book can be considered to be an attempt to appropriate colonial discourse and to construct a new narrative for the Khmers. After independence in 1953 French colonial discourse on Angkor was incorporated into Cam- bodian nationalism. While new repertoires such as Apsara Dance, modeled on the relief of the monuments, were created, the Buddhist Institute in Phnom Penh reprinted Thiounn’s book. Though the civil war was prolonged for 20 years and the Pol Pot regime rejected Cambodian cul- ture with the exception of the Angkor monuments, French colonial discourse is still alive in Cam- bodia today. -

Culture & History Story of Cambodia

CHAM CULTURE & HISTORY STORY OF CAMBODIA FARINA SO, VANNARA ORN - DOCUMENTATION CENTER OF CAMBODIA R KILLEAN, R HICKEY, L MOFFETT, D VIEJO-ROSE CHAM CULTURE & HISTORY STORYﺷﻤﺲ ISBN-13: 978-99950-60-28-2 OF CAMBODIA R Killean, R Hickey, L Moffett, D Viejo-Rose Farina So, Vannara Orn - 1 - Documentation Center of Cambodia ζរចងាំ និង យុត្ិធម៌ Memory & Justice មជ䮈មណ䮌លឯក羶រកម្宻ᾶ DOCUMENTATION CENTER OF CAMBODIA (DC-CAM) Villa No. 66, Preah Sihanouk Boulevard Phnom Penh, 12000 Cambodia Tel.: + 855 (23) 211-875 Fax.: + 855 (23) 210-358 E-mail: [email protected] CHAM CULTURE AND HISTORY STORY R Killean, R Hickey, L Moffett, D Viejo-Rose Farina So, Vannara Orn 1. Cambodia—Law—Human Rights 2. Cambodia—Politics and Government 3. Cambodia—History Funding for this project was provided by the UK Arts & Humanities Research Council: ‘Restoring Cultural Property and Communities After Conflict’ (project reference AH/P007929/1). DC-Cam receives generous support from the US Agency for International Development (USAID). The views expressed in this book are the points of view of the authors only. Include here a copyright statement about the photos used in the booklet. The ones sent by Belfast were from Creative Commons, or were from the authors, except where indicated. Copyright © 2018 by R Killean, R Hickey, L Moffett, D Viejo-Rose & the Documentation Center of Cambodia. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.