With Nicotine Replacement Therapies in Smoking Cessation Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

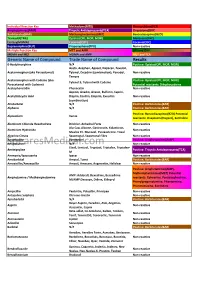

Cross Reaction Guide

Individual Reaction Key Methadone(MTD) Phencyclidine(PCP) Amphetamines(AMP) Tricyclic Antidepressants(TCA) Oxycodone(OXY) Barbiturates(BAR) Methamphetamines(MET) Benzodiazepines(BZO) Tramadol(TML) Opiates(OPI, MOP, MOR) Marijuana(THC) Ecstasy(MDMA) Cotinine(COT) Cocaine(COC) Buprenorphine(BUP) Propoxyphene(PPX) Non-reactive Multiple Reaction Key MET and AMP OPI and OXY MDMA and MET MDMA and AMP MET and TCA Generic Name of Compound Trade Name of Compound Results 6-Acetylmorphine N/A Positive: Opiates(OPI, MOP, MOR) Aceta, Acephen, Apacet, Dapacen, Feverall, Acetaminophen (aka Paracetamol) Tylenol, Excedrin (combination), Panadol, Non-reactive Tempra Acetaminophen with Codeine (aka Positive: Opiates(OPI, MOP, MOR) Tylenol 3, Tylenol with Codeine Paracetamol with Codeine) Potential reactants: Dihydrocodeine Acetophenetidin Phenacetin Non-reactive Aspirin, Anadin, Anasin, Bufferin, Caprin, Acetylsalicyclic Acid Disprin, Ecotrin, Empirin, Excedrin Non-reactive (combination) Allobarbital N/A Positive: Barbiturates(BAR) Alphenol N/A Positive: Barbiturates(BAR) Positive: Benzodiazepines(BZO) Potential Alprazolam Xanax reactants: Oxaprozin (Daypro), Sertraline Aluminum Chloride Hexahydrate Drichlor, Anhydrol Forte Non-reactive Alu-Cap, Alisone, Gastrocote, Kolanticon, Aluminum Hydroxide Non-reactive Maalox TC, Mucogel, Pyrogastrone, Topal Alverine Citrate Spasmonal, Spasmonal Fibre Non-reactive Amantadine Symmetrel Positive: Amphetamines(AMP) SpearesMedical.comAminopyrine N/A Non-reactive Elavil, Lentizol, Tryptizol, Triptafen, Triptafen- Amitriptyline -

In This Section

Strategic report In this section Chairman’s statement 2 CEO’s review 4 Business overview 6 The global context 8 Our business model 12 Our strategic priorities 14 How we performed 16 Risk management 18 Grow 20 Deliver 32 Simplify 44 Our financial architecture 48 Responsible business 50 Financial review 58 Strategic report Chairman’s statement Chairman’s statement To shareholders The value of the significant changes that have been made in recent years is evidenced in our performance this year “ Since Sir Andrew became It is clear from the following pages that Through the Audit & Risk Committee, we the Group made good progress against oversee the issues and challenges faced by CEO, the company has its strategy in 2013. management, and encourage the creation of an environment in which GSK can achieve The Board believes the business is seeing returned £30 billion its strategic ambitions in a responsible and the benefits of the significant changes the sustainable manner. to shareholders.” management team has driven over recent years to deliver sustainable growth, reduce risk and I have no doubt that commercial success is enhance returns to shareholders. directly linked to operating in a responsible way and which meets the changing expectations of The notably strong performance from the society. In this respect, the company continues R&D organisation in 2013 – with six major to adopt industry-leading positions on a range new product approvals in areas including of issues. respiratory disease, HIV and cancer – is critical to the longer-term prospects of the The announcement of plans during 2013 to Group. -

PDF (Irish Pharmacist January 2020)

EXCLUSIVE COVERAGE FROM THE RECENT IRISH MEDICATION SAFETY NETWORK ANNUAL CONFERENCE ABOUT-TURN WE LOOK AT WHAT MIGHT BE NEXT FOR PHARMACISTS FOLLOWING THE REVERSAL IN PROPOSED FEE CUTS DUMB AND DUMBER? ARE PHARMACISTS A LITTLE LACKING IN GREY MATTER WHEN IT COMES TO PRICING, ASKS FINTAN MOORE PLUS CLINICAL CONTENT: ASTHMA ❋ COPD ❋ EYE CARE ❋ SMOKING CESSATION TENDER CARE AT Every Change For topical use only. Cleanse and dry the affected area before applying. A copy of the summary of product characteristics is available upon request. The active ingredient in Caldesene Medicated Powder is Calcium Undecylenate 10% w/w, 20g, 55g, 100g pack size. For supply through general sale. PA 126/152/1 PA Holder: Clonmel Healthcare Ltd., Waterford Road, Clonmel, Co. Tipperary. Date Prepared: October 2019. 2019/ADV/CAL/150H NEW TREATS HEARTBURN AND ACID REFLUX. ONE TABLET PER DAY. LASTS 24 HOURS. AVAILABLE IN PACKS OF 7s AND 14s. Marketed by CCF:22656 Date of preparation: (10-19) ABBREVIATED PRESCRIBING INFORMATION Product Name: Emazole Control 20 mg Gastro-Resistant Tablets Composition: Each tablet contains 20 mg esomeprazole (as magnesium dihydrate). Description: Light pink oval film coated tablet. Indication(s): Proton Pump Inhibitor (PPI): Short-term treatment of reflux symptoms (e.g. heartburn and acid regurgitation) in adults. Dosage: Swallow tablets whole with liquid, do not chew or crush. Disperse in half a glass of non-carbonated water if difficulty in swallowing. Stir until tablets disintegrate, drink liquid with pellets immediately or within 15 min, or administer through a gastric tube. Do not chew or crush pellets. Adults: The recommended dose is 20 mg esomeprazole (one tablet) per day. -

Paul M Mahan Matthews

17 April 2015 PAUL McMAHAN MATTHEWS [email protected] PRIMARY APPOINTMENTS July, 2014- Edmond and Lily Safra Professor of Translational Neuroscience and Therapeutics, Division of Brain Sciences, Department of Medicine, Imperial College London Secured endowment for, and first holder of, new Chair associated with the Divisional Head and posts (Edmond and Lily Safra Scholars) accompanying its foundation. April, 2012- Professor and Head, Division of Brain Sciences, Department of Medicine, Imperial College London Leading a new integration of over 70 academics all clinical and basic neurosciences, neuropsychopharmacology, neurology and mental health within a Division of 200 staff in the Faculty of Medicine with senior management responsibilities across the three academic hospital sites of Imperial College, London. Additional responsibilities as Deputy Director (2008- ) of the Wellcome Trust- GSK Translational Medicine Training Programme, Deputy Director (2011- ) of the BRC Institute for Translational Medicine and Therapeutics, Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) Theme Lead for Neuroscience, co-Director of the Neurotechnology Network and the EPSRC Centre for Doctoral Training in Neurology and Research Advisory Board for the Data Science Institute. July, 2012- February 2014 Vice-President for Integrative Medicines Development, Neurosciences and Medicine Development Lead, GlaxoSmithKline (joint appointment with Imperial College) Leading late phase development programme. Senior advisor to the Head of Neurosciences and China R and D with specific -

Formulation of Novel Buccal Mucosal Drug Delivery Systems for Nicotine Replacement Therapy (Nrt)

FORMULATION OF NOVEL BUCCAL MUCOSAL DRUG DELIVERY SYSTEMS FOR NICOTINE REPLACEMENT THERAPY (NRT). OBINNA CHIKWADO OKEKE A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Greenwich for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2017 DECLARATION “I certify that this work has not been accepted in substance for any degree, and is not concurrently being submitted for any purpose. I also declare that this work is the result of my own investigations except where otherwise identified by references and that I have not plagiarised another’s work”. Mr. Obinna C. Okeke (Candidate) Dr J.S. Boateng (First supervisor) i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor, Dr Joshua Boateng, for his enormous support, encouragement and general guidance throughout my research. His constant support and encouragement has led me to believe in myself and give out my best. I also appreciate the University of Greenwich for providing the facilities and student support within this period. I would like to acknowledge Dr Ian Slipper for all SEM and XRPD techniques as well as Devyani Amin for HPLC analysis. Thanks to all University staff for supporting my program. I also want to extend my deepest gratitude to my family. Their support and encouragement have led me to the person I am today. I am grateful to Dr Sam and Samantha Owusu-Ware and family for their support. Finally, to all my roommates, officemates, library IT and assistance team, project students under my supervision and fellow postgraduate students, I want to say I big thank you for your support. -

Malta Medicines List April 08

Defined Daily Doses Pharmacological Dispensing Active Ingredients Trade Name Dosage strength Dosage form ATC Code Comments (WHO) Classification Class Glucobay 50 50mg Alpha Glucosidase Inhibitor - Blood Acarbose Tablet 300mg A10BF01 PoM Glucose Lowering Glucobay 100 100mg Medicine Rantudil® Forte 60mg Capsule hard Anti-inflammatory and Acemetacine 0.12g anti rheumatic, non M01AB11 PoM steroidal Rantudil® Retard 90mg Slow release capsule Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitor - Acetazolamide Diamox 250mg Tablet 750mg S01EC01 PoM Antiglaucoma Preparation Parasympatho- Powder and solvent for solution for mimetic - Acetylcholine Chloride Miovisin® 10mg/ml Refer to PIL S01EB09 PoM eye irrigation Antiglaucoma Preparation Acetylcysteine 200mg/ml Concentrate for solution for Acetylcysteine 200mg/ml Refer to PIL Antidote PoM Injection injection V03AB23 Zovirax™ Suspension 200mg/5ml Oral suspension Aciclovir Medovir 200 200mg Tablet Virucid 200 Zovirax® 200mg Dispersible film-coated tablets 4g Antiviral J05AB01 PoM Zovirax® 800mg Aciclovir Medovir 800 800mg Tablet Aciclovir Virucid 800 Virucid 400 400mg Tablet Aciclovir Merck 250mg Powder for solution for inj Immunovir® Zovirax® Cream PoM PoM Numark Cold Sore Cream 5% w/w (5g/100g)Cream Refer to PIL Antiviral D06BB03 Vitasorb Cold Sore OTC Cream Medovir PoM Neotigason® 10mg Acitretin Capsule 35mg Retinoid - Antipsoriatic D05BB02 PoM Neotigason® 25mg Acrivastine Benadryl® Allergy Relief 8mg Capsule 24mg Antihistamine R06AX18 OTC Carbomix 81.3%w/w Granules for oral suspension Antidiarrhoeal and Activated Charcoal -

TOX/See Drug Screen Test

LB0004363 TM TOX/See Drug Screen Test TOX/See TM Cross-Reactivity Table by Trade Name This document is for informational use only; it is not intended to replace confirmative testing. TOX/See TM Drug Screen Test CONCENTRATION COMPOUND (Generic Name) COMPOUND (Trade Name) RESULTS FOR POSITIVE Abacavir Ziagen Non-reactive ,, Acamprosate Campral Non-reactive Acetaminophen (See also Paracetamol) Aceta Non-reactive Acetaminophen (See also Paracetamol) Acephen Non-reactive Acetaminophen (See also Paracetamol) Apacet Non-reactive Acetaminophen (See also Paracetamol) Dapacen Non-reactive Acetaminophen (See also Paracetamol) Feverall Non-reactive ' ' ·,, Acetaminophen (See also Paracetamol) Tylenol Non-reactive ' Acetaminophen (See also Paracetamol) Excedrin (combination) Non-reactive ,, ' :· Acetaminophen (See also Paracetamol) Panadol Non-reactive f.,1· ··<!:•:•· •: '; ,.; .. ·,. Acetaminophen (See also Paracetamol) Tempra Non-reactive ):., '' ·.·~- with Codeine Positive for Opiates MOR= 300 ng/ml Acetaminophen Tylenol3 l<see also Paracetamol with codeine) I(OPI , MOR) OPI = 2,000 ng/ml Positive for Opiates MOR= 300 ng/ml Acetaminophen with Codeine Tylenol with codeine l(see also Paracetamol with codeine) I<OPI, MOR) OPI = 2,000 ng/ml Acetic Acid Ethanoic Acid Non-reactive ~:~w-~{'"·.:;; .. Acetophenetidin Phenacetin Non-reactive f<:;~·§;~j.,;:; ~::: Acetylsalicyclic acid Aspirin Non-reactive 'f.~;k;,';J~:,·; ';~rr. Acetylsalicyclic acid Anadin Non-reactive ' ;': ' f.i~:j~ :;f.: ~. '• Acetylsalicyclic acid Ana sin Non-reactive 1 ;.;:·.\~~·~:;:~, -

OUH Formulary Approved for Use in Breast Surgery

Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Formulary FORMULARY (Y): the medicine can be used as per its licence. RESTRICTED FORMULARY (R): the medicine can be used as per the agreed restriction. NON-FORMULARY (NF): the medicine is not on the formulary and should not be used unless exceptional approval has been obtained from MMTC. UNLICENSED MEDICINE – RESTRICTED FORMULARY (UNR): the medicine is unlicensed and can be used as per the agreed restriction. SPECIAL MEDICINE – RESTRICTED FORMULARY (SR): the medicine is a “special” (unlicensed) and can be used as per the agreed restriction. EXTEMPORANEOUS PREPARATION – RESTRICTED FORMULARY (EXTR): the extemporaneous preparation (unlicensed) can be prepared and used as per the agreed restriction. UNLICENSED MEDICINE – NON-FORMULARY (UNNF): the medicine is unlicensed and is not on the formulary. It should not be used unless exceptional approval has been obtained from MMTC. SPECIAL MEDICINE – NON-FORMULARY (SNF): the medicine is a “special” (unlicensed) and is not on the formulary. It should not be used unless exceptional approval has been obtained from MMTC. EXTEMPORANEOUS PREPARATION – NON-FORMULARY (EXTNF): the extemporaneous preparation (unlicensed) cannot be prepared and used unless exceptional approval has been obtained from MMTC. CLINICAL TRIALS (C): the medicine is clinical trial material and is not for clinical use. NICE TECHNOLOGY APPRAISAL (NICETA): the medicine has received a positive appraisal from NICE. It will be available on the formulary from the day the Technology Appraisal is published. Prescribers who wish to treat patients who meet NICE criteria, will have access to these medicines from this date. However, these medicines will not be part of routine practice until a NICE TA Implementation Plan has been presented and approved by MMTC (when the drug will be given a Restricted formulary status). -

GSK Annual Report 2002

The Impact of Medicines Do more, feel better, live longer Annual Report 2002 www.gsk.com Mission Our global quest is to improve the quality of human life by enabling people to do more, feel better and live longer. Our Spirit We undertake our quest with the enthusiasm of entrepreneurs, excited by the constant search for innovation. We value performance achieved with integrity. We will attain success as a world class global leader with each and every one of our people contributing with passion and an unmatched sense of urgency. Strategic Intent We want to become the indisputable leader in our industry. GlaxoSmithKline plc is an English public limited company. Its shares are listed on the London Stock Exchange and the New York Stock Exchange. GlaxoSmithKline plc acquired Glaxo Wellcome plc and SmithKline Beecham plc on 27th December 2000 by way of a scheme of arrangement for the merger of the two companies which became effective on 27th December 2000. This report is the Annual Report of GlaxoSmithKline plc for the year ended 31st December 2002. It comprises in a single document the Annual Report of the company in accordance with United Kingdom requirements and the Annual Report on Form 20-F to the Securities and Exchange Commission in the United States of America. A summary report on the year, the Annual Review 2002, intended for the investor not needing the full detail of the Annual Report, is produced as a separate document. The Annual Review includes the joint statement by the Chairman and the Chief Executive Officer, a summary review of operations, summary financial statements and a summary remuneration report. -

Formulary 12 Edition

Drug and Therapeutics Committee Formulary 12 th Edition Version14.3 July 2015 Compiled on behalf of the Drug and Therapeutics Committee by Eleanore Atkinson Medicines Information Pharmacist Formulary 12 th Edition [v14.3] Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 11 Purpose ............................................................................................................................................... 11 How to use this Formulary .................................................................................................................. 11 Prescribing Formulary drugs............................................................................................................... 11 Prescribing a non-Formulary drug ...................................................................................................... 11 Procedure for additions to and amendment of the Formulary ............................................................. 11 Prescribing information ....................................................................................................................... 12 Filling in prescription charts ............................................................................................................... 12 Intravenous antibiotics ........................................................................................................................ 12 Controlled drugs ................................................................................................................................ -

Copyright Notice

www.generics-bulletin.com Bulletin Publishing Group 4 Poplar Road, Dorridge, Solihull B93 8DB, UK Tel: +44 (0)1564 777550 Fax: +44 (0)1564 777524 E-mail: [email protected] COPYRIGHT NOTICE This publication must not be forwarded, exported, distributed or circulated by any means or in any format to persons including clients outside the direct employment of your Company. You may distribute the publication internally, but you may incorporate only insubstantial extracts, abstractsbulletin or summaries into presentations, providing Generics is identified as the source of the information. bulletin bulletin The publication/s, Generics and/or News@Generics , in PDF and/or HTML format, are supplied to you strictly under the terms and conditions of the Global Licence agreement between your Company and OTC Publications Ltd, the copyright holder of the publications. The publication/s are the intellectual property of the Publisher, OTC Publications Ltd and are protected by English copyright, trademark and other laws. Bulletin Publishing Group is a division of OTC Publications Ltd Registered Office: 4 Poplar Road, Dorridge, Solihull B93 8DB, UK. Registered in England No 2765878 Gen 21/3/14 Pg. 1_Gen 18/11/05 Pg. 1 17/03/2014 19:47 Page 1 21 March 2014 COMPANY NEWS 2 Council fits missing part Alvotech finesses its biotech production 2 Sun facility suffers an FDAimportalert 3 Lannett pursues buys as sales shoot ahead 4 Hikma commits to its US Generics unit 5 into patent courtpuzzle Aspen wants partner to push into Japan 6 legal compromise reached by the Council of the European Union (EU) is “the last ScinoPharm benefits from 7 focus on Japan Amissing part forthe establishment of Europe-wide patent protection” through aUnified Patent Court, the European Commissionhas claimed. -

Cross Reaction Book

Toxicology Services Master Cross-Reaction List Toxicology Services Immunoassay and Cross-Reactants Immunoassay-based screening methods provide high sensitivity but may be susceptible to specificity issues. Cross-reactivity of structurally similar substances may occur with immunoassay methodologies, potentially yielding false results. Immunoassay manufacturers test for common potential interfering substances and list those results in package inserts; however, testing every compound is not feasible. High doses of a single drug or concurrent dosing of multiple drugs may significantly influence urine immunoassay results. These clinical scenarios are difficult to replicate in a bench setting during the immunoassay development process and, as such, may only become known once the assay is introduced to the market. The attached contains potential reactants and cross-reactants with most immunoassay methodologies. This list is not all inclusive. Other substances and/or technical or procedural factors may interfere with the test and cause false results. For the most current information relative to the immunoassay testing methodology utilized at your facility, refer to the package insert provided by the manufacturer of your kits or contact your manufacturer directly. All positive results from onsite drug testing are presumptive and should be confirmed by a laboratory using an alternative methodology such as Liquid Chromatography / Mass Spectroscopy (LC/MS) or Gas Chromatography / Mass Spectrometry (GC/MS). Toxicology Services Potential Immunoassay