CARREIRO-DISSERTATION.Pdf (619.2Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

German Jewish Refugees in the United States and Relationships to Germany, 1938-1988

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO “Germany on Their Minds”? German Jewish Refugees in the United States and Relationships to Germany, 1938-1988 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Anne Clara Schenderlein Committee in charge: Professor Frank Biess, Co-Chair Professor Deborah Hertz, Co-Chair Professor Luis Alvarez Professor Hasia Diner Professor Amelia Glaser Professor Patrick H. Patterson 2014 Copyright Anne Clara Schenderlein, 2014 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Anne Clara Schenderlein is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically. _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ Co-Chair _____________________________________________________________________ Co-Chair University of California, San Diego 2014 iii Dedication To my Mother and the Memory of my Father iv Table of Contents Signature Page ..................................................................................................................iii Dedication ..........................................................................................................................iv Table of Contents ...............................................................................................................v -

The Eddie Awards Issue

THE MAGAZINE FOR FILM & TELEVISION EDITORS, ASSISTANTS & POST- PRODUCTION PROFESSIONALS THE EDDIE AWARDS ISSUE IN THIS ISSUE Golden Eddie Honoree GUILLERMO DEL TORO Career Achievement Honorees JERROLD L. LUDWIG, ACE and CRAIG MCKAY, ACE PLUS ALL THE WINNERS... FEATURING DUMBO HOW TO TRAIN YOUR DRAGON: THE HIDDEN WORLD AND MUCH MORE! US $8.95 / Canada $8.95 QTR 1 / 2019 / VOL 69 Veteran editor Lisa Zeno Churgin switched to Adobe Premiere Pro CC to cut Why this pro chose to switch e Old Man & the Gun. See how Adobe tools were crucial to her work ow and to Premiere Pro. how integration with other Adobe apps like A er E ects CC helped post-production go o without a hitch. adobe.com/go/stories © 2019 Adobe. All rights reserved. Adobe, the Adobe logo, Adobe Premiere, and A er E ects are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Adobe in the United States and/or other countries. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. Veteran editor Lisa Zeno Churgin switched to Adobe Premiere Pro CC to cut Why this pro chose to switch e Old Man & the Gun. See how Adobe tools were crucial to her work ow and to Premiere Pro. how integration with other Adobe apps like A er E ects CC helped post-production go o without a hitch. adobe.com/go/stories © 2019 Adobe. All rights reserved. Adobe, the Adobe logo, Adobe Premiere, and A er E ects are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Adobe in the United States and/or other countries. -

Dean Tavoularis

DEAN TAVOULARIS Né aux États-Unis Il vit et travaille à Paris. Directeur artistique de films et artiste- peintre, il compte plus de 50 ans de carrière aux côtés de metteurs en scène de légende … Arthur Penn, Michelangelo Antonioni, Wim Wenders, Francis Ford on les nomme à Hollywood –, ils ont Coppola, Roman Polanski. posé les jalons d’un corps essentiel du cinéma : donner une matière aux visions L’artiste, né en 1932 à Lowell dans le d’un cinéaste. Parmi leurs successeurs, Massachusetts, de parents grecs originaires Dean Tavoularis s’est imposé comme du Péloponnèse, arrive à l’âge de 4 ans à le plus précieux, précis et inventif. Son Long Beach en Californie. regard sidérant n’est pas étranger à la Son père travaille dans la compagnie de réussite de Coppola : nous lui devons café familiale. Son environnement familial les salons opaques du Parrain, les néons encourage les goûts du jeune Dean pour le luminescents de Coup de cœur, la folie dessin et les beaux-arts et à 17 ans il intègre sauvage du labyrinthe où les personnages une des premières Film School des Etats- d’Apocalypse Now s’égarent – ainsi que les Unis et rejoint les studios Disney, qui font costumes des bunnies Playboy. Sa vision ne véritablement office d’école de cinéma. En se limite pas à son domaine, elle englobe parallèle il suit des cours d’architecture, de le projet dans sa totalité. » écrit Léonard dessin et d’art. Son apprentissage au sein Bloom dans un article de Numéro consacré des studios Disney lui permet de mettre à Dean Tavoularis (avril 2019). -

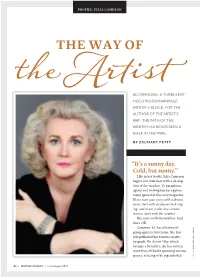

THE WAY of PROFILE: JULIA CAMERON “It’S Asunny Day

PROFILE: JULIA CAMERON THE WAY OF ALCOHOLISM. A TURBULENT HOLLYWOOD MARRIAGE. WRITER’S BLOCK. FOR THE AUTHOR OF THE ARTIST’S WAY, THE PATH OF THE WRITER HAS NEVER BEEN A WALK IN THE PARK. BY ZACHARY PETIT “It’s a sunny day. Cold, but sunny.” Like in her books, Julia Cameron begins our interview with a descrip- tion of the weather. To paraphrase agents and writing teachers galore, many quoted in this very magazine: Never start your story with a dream; never start with an alarm clock ring- ing; and never, under any circum- stances, start with the weather. She starts with the weather. And that’s OK. Cameron, 63, has a history of going against convention: She first self-published her famous creativ- ity guide The Artist’s Way, which became a bestseller; she has written MARK STEPHEN KORNBLUTH more than 30 books spanning various genres, refusing to be pigeonholed PHOTO © 46 I WRITER’S DIGEST I July/August 2011 into any one; she battled mental ill- of many she’d face in her journey to “It was probably perfect,” she says. ness and alcoholism without letting become a writer. Cameron had come “Because if you’re trying to write and her struggles define her; and, despite in as an Italian major, but she wanted you have unlimited time, you can being one of the most lauded, read to switch to English—and when procrastinate an unlimited account, and respected writing and creativ- she consulted one of the people in but if you have limited time, you ity self-help gurus, she’s occasionally charge, she didn’t exactly get the help rush to the page trying to get some- haunted by self-doubt and bur- she was looking for. -

Scorses by Ebert

Scorsese by Ebert other books by An Illini Century roger ebert A Kiss Is Still a Kiss Two Weeks in the Midday Sun: A Cannes Notebook Behind the Phantom’s Mask Roger Ebert’s Little Movie Glossary Roger Ebert’s Movie Home Companion annually 1986–1993 Roger Ebert’s Video Companion annually 1994–1998 Roger Ebert’s Movie Yearbook annually 1999– Questions for the Movie Answer Man Roger Ebert’s Book of Film: An Anthology Ebert’s Bigger Little Movie Glossary I Hated, Hated, Hated This Movie The Great Movies The Great Movies II Awake in the Dark: The Best of Roger Ebert Your Movie Sucks Roger Ebert’s Four-Star Reviews 1967–2007 With Daniel Curley The Perfect London Walk With Gene Siskel The Future of the Movies: Interviews with Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, and George Lucas DVD Commentary Tracks Beyond the Valley of the Dolls Casablanca Citizen Kane Crumb Dark City Floating Weeds Roger Ebert Scorsese by Ebert foreword by Martin Scorsese the university of chicago press Chicago and London Roger Ebert is the Pulitzer The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 Prize–winning film critic of the Chicago The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London Sun-Times. Starting in 1975, he cohosted © 2008 by The Ebert Company, Ltd. a long-running weekly movie-review Foreword © 2008 by The University of Chicago Press program on television, first with Gene All rights reserved. Published 2008 Siskel and then with Richard Roeper. He Printed in the United States of America is the author of numerous books on film, including The Great Movies, The Great 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 1 2 3 4 5 Movies II, and Awake in the Dark: The Best of Roger Ebert, the last published by the ISBN-13: 978-0-226-18202-5 (cloth) University of Chicago Press. -

Oscar®-Nominated Production Designer Jim Bissell to Receive Lifetime Achievement Award at 19Th Annual Art Directors Guild Awards on January 31, 2015

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE OSCAR®-NOMINATED PRODUCTION DESIGNER JIM BISSELL TO RECEIVE LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT AWARD AT 19TH ANNUAL ART DIRECTORS GUILD AWARDS ON JANUARY 31, 2015 LOS ANGELES, July 15, 2014 — Emmy®-winning and Oscar®-nominated Production Designer Jim Bissell will receive the Art Directors Guild’s Lifetime Achievement Award at the 19th Annual Excellence in Production Design Awards on January 31, 2015 at a black- tie ceremony at the Beverly Hilton Hotel. The announcement was made today by John Shaffner, ADG Council Chairman, and ADG Award Producers Dave Blass and James Pearse Connelly. “Jim Bissell’s work as a Production Designer is legendary and we are proud to rank him among the best in the history of our profession. He is an extraordinary artist and accomplished leader in the industry and it is our pleasure to name him as this year’s Lifetime Achievement Award recipient,” said Shaffner. A veteran leader of the ADG, Bissell was a past Vice President and a Board member for more than 15 years. He also chaired the Guild’s Awards Committee for the first three years of its existence. Bissell’s distinguished work can be seen on such notable films as E.T. the Extra- Terrestrial (1982), which took home four Oscars® with an additional five Oscar® nominations in 1983; The Rocketeer (1991), Jumanji (1995), 300 (2006), Mission: Impossible – Ghost Protocol (2011) and most recently The Monuments Men (2014), directed by and starring George Clooney. Monuments Men is Jim’s fourth collaboration with Clooney, which began with Confessions of a Dangerous Mind (2002), followed with Oscar®-nominated Good Night, and Good Luck (2005) and continuing with Leatherheads (2007). -

Bamcinématek Presents Joe Dante at the Movies, 18 Days of 40 Genre-Busting Films, Aug 5—24

BAMcinématek presents Joe Dante at the Movies, 18 days of 40 genre-busting films, Aug 5—24 “One of the undisputed masters of modern genre cinema.” —Tom Huddleston, Time Out London Dante to appear in person at select screenings Aug 5—Aug 7 The Wall Street Journal is the title sponsor for BAMcinématek and BAM Rose Cinemas. Jul 18, 2016/Brooklyn, NY—From Friday, August 5, through Wednesday, August 24, BAMcinématek presents Joe Dante at the Movies, a sprawling collection of Dante’s essential film and television work along with offbeat favorites hand-picked by the director. Additionally, Dante will appear in person at the August 5 screening of Gremlins (1984), August 6 screening of Matinee (1990), and the August 7 free screening of rarely seen The Movie Orgy (1968). Original and unapologetically entertaining, the films of Joe Dante both celebrate and skewer American culture. Dante got his start working for Roger Corman, and an appreciation for unpretentious, low-budget ingenuity runs throughout his films. The series kicks off with the essential box-office sensation Gremlins (1984—Aug 5, 8 & 20), with Zach Galligan and Phoebe Cates. Billy (Galligan) finds out the hard way what happens when you feed a Mogwai after midnight and mini terrors take over his all-American town. Continuing the necessary viewing is the “uninhibited and uproarious monster bash,” (Michael Sragow, New Yorker) Gremlins 2: The New Batch (1990—Aug 6 & 20). Dante’s sequel to his commercial hit plays like a spoof of the original, with occasional bursts of horror and celebrity cameos. In The Howling (1981), a news anchor finds herself the target of a shape-shifting serial killer in Dante’s take on the werewolf genre. -

Wmc Investigation: 10-Year Analysis of Gender & Oscar

WMC INVESTIGATION: 10-YEAR ANALYSIS OF GENDER & OSCAR NOMINATIONS womensmediacenter.com @womensmediacntr WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER ABOUT THE WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER In 2005, Jane Fonda, Robin Morgan, and Gloria Steinem founded the Women’s Media Center (WMC), a progressive, nonpartisan, nonproft organization endeav- oring to raise the visibility, viability, and decision-making power of women and girls in media and thereby ensuring that their stories get told and their voices are heard. To reach those necessary goals, we strategically use an array of interconnected channels and platforms to transform not only the media landscape but also a cul- ture in which women’s and girls’ voices, stories, experiences, and images are nei- ther suffciently amplifed nor placed on par with the voices, stories, experiences, and images of men and boys. Our strategic tools include monitoring the media; commissioning and conducting research; and undertaking other special initiatives to spotlight gender and racial bias in news coverage, entertainment flm and television, social media, and other key sectors. Our publications include the book “Unspinning the Spin: The Women’s Media Center Guide to Fair and Accurate Language”; “The Women’s Media Center’s Media Guide to Gender Neutral Coverage of Women Candidates + Politicians”; “The Women’s Media Center Media Guide to Covering Reproductive Issues”; “WMC Media Watch: The Gender Gap in Coverage of Reproductive Issues”; “Writing Rape: How U.S. Media Cover Campus Rape and Sexual Assault”; “WMC Investigation: 10-Year Review of Gender & Emmy Nominations”; and the Women’s Media Center’s annual WMC Status of Women in the U.S. -

Avid Customers Stand out Among 2005 Academy Award Nominees

Avid Customers Stand Out Among 2005 Academy Award Nominees TEWKSBURY, Mass.--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Feb. 1, 2005-- Creators use one or more Avid solutions on films nominated in the Best Picture, Directing, Film Editing, Sound Editing, Sound Mixing, Visual Effects, and Best Animated Feature categories Avid Technology, Inc. (NASDAQ: AVID) today announced that solutions from its Avid®, Digidesign®, and Softimage® product families were used in the creation of every film nominated in the Best Picture, Directing, Film Editing, Sound Editing, Sound Mixing, Visual Effects, and Best Animated Feature categories of the 77th Annual Academy Awards®. The widespread use of Avid's systems among films nominated for Academy Awards this year confirms the company's continuing leadership position in the digital content creation industry. "We're delighted that our products continue to be the preferred postproduction tools for the creative storytellers behind so many of this year's Academy Award nominees," said David Krall, president and chief executive officer of Avid. "Because many of our engineers and product designers are filmmakers themselves, we're able to innovate new products - and entire production workflows - that address the complex needs of the filmmaking process. Our product development scope not only includes building world-class nonlinear editing systems, but encompasses audio editing, sound design, visual effects creation, finishing, and asset management capabilities into a powerful workflow. We then make all these capabilities transparent - so our -

RETROSPECTIVA SCORSESE 24 De Janeiro a 20 De Fevereiro De 2020 Programação 24/01 SEX 15H CURTAS | 57'| What's a Nice Girl L

RETROSPECTIVA SCORSESE 24 de janeiro a 20 de fevereiro de 2020 Programação 24/01 SEX 15h CURTAS | 57’| What's a Nice Girl Like You Doing in a Place Like This?, de Martin Scorsese (EUA, 1963) | | 9’ It's Not Just You, Murray!, de Martin Scorsese (EUA, 1964) | 15’ The Big Shave, de Martin Scorsese (EUA, 1968) | 6’ Michael Jackson: Bad, de Martin Scorsese (EUA, 1987) | 17’ The Key to Reserva, de Martin Scorsese (EUA, 2007) | 10’ 16h15 Quem Bate à Minha Porta?, de Martin Scorsese (I Call First, EUA, 1967) | 16 anos | 90’ 18h Sexy e Marginal, de Martin Scorsese (Boxcar Bertha, EUA, 1972) | 14 anos | 88’ 20h Caminhos Perigosos, de Martin Scorsese (Mean Streets, EUA, 1973) | 112’ 25/01 SÁB 15h Alice Não Mora Mais Aqui, de Martin Scorsese (Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore, EUA, 1974) | 14 anos | 112’ 17h15 Taxi Driver, de Martin Scorsese (EUA, 1976) | 16 anos | 113’ 19h30 New York, New York, de Martin Scorsese (EUA, 1977) | 10 anos | 155’ 26/01 DOM 18h O Último Concerto de Rock, de Martin Scorsese (The Last Waltz, EUA, 1978) | Livre | 117’ 20h15 Touro Indomável, de Martin Scorsese (Raging Bull, EUA, 1980) | 16 anos| 129’ 27/01 SEG 15h A Cor do Dinheiro, de Martin Scorsese (The Color of Money, EUA, 1986) | 12 anos | 119’ 17h15 O Rei da Comédia, de Martin Scorsese (The King of Comedy, EUA, 1982) | 12 anos | 109’ 19h15 Depois de Horas, de Martin Scorsese (After Hours, EUA, 1985) | 16 anos | 97’ 21h Contos de Nova York, de Martin Scorsese; Francis Ford Coppola; Woody Allen (New York Stories, EUA, 1989) | 14 anos | 124’ 28/01 TER 15h A Última Tentação -

The Field Guide to Sponsored Films

THE FIELD GUIDE TO SPONSORED FILMS by Rick Prelinger National Film Preservation Foundation San Francisco, California Rick Prelinger is the founder of the Prelinger Archives, a collection of 51,000 advertising, educational, industrial, and amateur films that was acquired by the Library of Congress in 2002. He has partnered with the Internet Archive (www.archive.org) to make 2,000 films from his collection available online and worked with the Voyager Company to produce 14 laser discs and CD-ROMs of films drawn from his collection, including Ephemeral Films, the series Our Secret Century, and Call It Home: The House That Private Enterprise Built. In 2004, Rick and Megan Shaw Prelinger established the Prelinger Library in San Francisco. National Film Preservation Foundation 870 Market Street, Suite 1113 San Francisco, CA 94102 © 2006 by the National Film Preservation Foundation Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Prelinger, Rick, 1953– The field guide to sponsored films / Rick Prelinger. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN 0-9747099-3-X (alk. paper) 1. Industrial films—Catalogs. 2. Business—Film catalogs. 3. Motion pictures in adver- tising. 4. Business in motion pictures. I. Title. HF1007.P863 2006 011´.372—dc22 2006029038 CIP This publication was made possible through a grant from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. It may be downloaded as a PDF file from the National Film Preservation Foundation Web site: www.filmpreservation.org. Photo credits Cover and title page (from left): Admiral Cigarette (1897), courtesy of Library of Congress; Now You’re Talking (1927), courtesy of Library of Congress; Highlights and Shadows (1938), courtesy of George Eastman House. -

October 11, 2011 (XXIII:7) Arthur Penn, BONNIE and CLYDE (1967, 112 Min)

October 11, 2011 (XXIII:7) Arthur Penn, BONNIE AND CLYDE (1967, 112 min) Directed by Arthur Penn Writing credits David Newman & Robert Benton and Robert Towne (uncredited) Produced by Warren Beatty Original Music by Charles Strouse Cinematography by Burnett Guffey Film Editing by Dede Allen Art Direction by Dean Tavoularis Costume Design by Theadora Van Runkle Earl Scruggs....composer: Foggy Mountain Breakdown Alan Hawkshaw....musician: "The Ballad of Bonnie and Clyde" Warren Beatty...Clyde Barrow Faye Dunaway...Bonnie Parker Michael J. Pollard...C.W. Moss Gene Hackman...Buck Barrow Estelle Parsons...Blanche Denver Pyle...Frank Hamer DAVID NEWMAN (February 4, 1937, New York City, New York Dub Taylor...Ivan Moss – June 27, 2003, New York City, New York) has 18 writing Evans Evans...Velma Davis credits: 2000 Takedown, 1997 “Michael Jackson: His Story on Gene Wilder...Eugene Grizzard Film - Volume II”, 1985 Santa Claus, 1984 Sheena: Queen of the Jungle, 1983 Superman II, 1982 Still of the Night, 1982 Jinxed!, Oscars for Best Actress in a Supporting Role (Estelle 1980 Superman II, 1978 Superman, 1975 “Superman”, 1972 Bad Parsons)and Best Cinematography (Burnett Guffey). Selected for Company, 1972 Oh! Calcutta!, 1972 What's Up, Doc?, 1970 National Film Registry – 1992 There Was a Crooked Man..., and 1967 Bonnie and Clyde. BONNIE PARKER (October 1, 1910-May 23, 1934). ROBERT BENTON (September 28, 1932, Waxahachie, Texas – ) won Best Writing Oscars for Places in the Heart (1984) and (March 24, 1909-May 23-1934). Kramer v. Kramer (1979); he also