Bridging the Gap Between Theory and Lived Experience in Formation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thesoutherncross

The SSoouutthheerrnnCCrroossss January 29 to February 4, 2014 Reg No. 1920/002058/06 No 4859 www.scross.co.za R7,00 (incl VAT RSA) Rabbi speaks New columnist Daswa & Pfanner: on his friend, on how The making Pope Francis faith grows of local saints Page 5 Page 7 Page 9 South Africa gives Palestinians hope BY CLAIRE MATHIESON Secretary of State John Kerry was meeting with key players to discuss a peace deal be - OUTH AFRICA’S experience of overcom - tween Israel and Palestine. ing apartheid is giving hope to Palestini - “The way forward has to be around nego - Sans in the occupied West Bank and Gaza, tiation. There needs to be some kind of level many of whom display posters of Nelson playing field between Israel and Palestine,” Mandela in their homes. Fr Pearson told The Southern Cross . Archbishop Stephen Brislin of Cape Town, The delegation spoke to diplomats and president of the Southern African Catholic key negotiators as well as people on the Bishops’ Conference, and Fr Peter-John Pear - ground and Church leaders working in the son, director of the Catholic Parliamentary Holy Land. Liaison Office, were part of a visit to the re - gion by the Co-ordination of Bishops’ Con - ather Pearson said the journey into ferences in support of the Church in the Gaza—“the world’s biggest open air Holy Land, which also included bishops F prison”—was “extremely moving and chal - from Europe and North America. lenging”. “Gaza is a man-made disaster, a shocking “It’s a desperate situation. There are 1,8 scandal, an injustice that cries out to the human community for a resolution,” the million people living in an entirely blocked bishops said in a statement after their visit off area. -

Women and Men Entering Religious Life: the Entrance Class of 2018

February 2019 Women and Men Entering Religious Life: The Entrance Class of 2018 Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate Georgetown University Washington, DC Women and Men Entering Religious Life: The Entrance Class of 2018 February 2019 Mary L. Gautier, Ph.D. Hellen A. Bandiho, STH, Ed.D. Thu T. Do, LHC, Ph.D. Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 1 Major Findings ................................................................................................................................ 2 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Part I: Characteristics of Responding Institutes and Their Entrants Institutes Reporting New Entrants in 2018 ..................................................................................... 7 Gender ............................................................................................................................................. 8 Age of the Entrance Class of 2018 ................................................................................................. 8 Country of Birth and Age at Entry to United States ....................................................................... 9 Race and Ethnic Background ........................................................................................................ 10 Religious Background .................................................................................................................. -

5211 SCHLUTER ROAD MONONA, WI 53716-2598 CITY HALL (608) 222-2525 FAX (608) 222-9225 for Immediate

5211 SCHLUTER ROAD MONONA, WI 53716-2598 CITY HALL (608) 222-2525 FAX (608) 222-9225 http://www.mymonona.com For Immediate Release Contact: Bryan Gadow, City Administrator [email protected] Monona Reaches Agreement with St. Norbert Abbey to Purchase nearly 10 Acres on Lake Monona The City of Monona has reached agreement with St. Norbert Abbey of De Pere to purchase the historic San Damiano property at 4123 Monona Drive. The purchase agreement, in the amount of $8.6M, was unanimously approved by the Monona City Council at the September 8th meeting. Pending approval by the Vatican as required by canon law, if all goes as planned Monona will take ownership of the property in June 2021. “We are very excited to have reached an agreement with St. Norbert Abbey to purchase the San Damiano property. This is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for Monona to significantly increase public access to the lakefront and waters of Lake Monona in addition to increasing our public open space. While Monona enjoys more than four miles of shoreline, over eighty percent of Monona residents would not have lake access were it not for our smaller parks and launches. It will be a tremendous asset for the City,” said Monona Mayor Mary O’Connor. At just under ten acres, San Damiano includes over 1,000 feet of frontage on Lake Monona. Much of the grounds are wooded. The house and property are part of the original farm developed by Allis-Chalmers heir Frank Allis in the 1880’s. The land, as is true of much of the area, was originally inhabited by Native Americans, including ancestors of the Ho- Chunk Nation. -

SECULAR CONSECRATION: Section Two - Chapter One

SECULAR CONSECRATION: Section Two - Chapter One We now come to the heart of what membership in a secular Institute entails, what distinguishes it from other associations of the faithful. It is the full profession of the evangelical councils of celibate chastity, poverty and obedience. Secular institutes are parallel to Religious institutes such as Jesuits and Franciscans in that both profess the evangelical counsels and are recognized by the Church. Other associations may live in the “spirit” of the counsels such as “Third Orders” (often now called “secular orders”) which often creates confusion between them and secular institutes but there are key differences. Third orders do not profess vows and do not commit themselves to lives of celibate chastity. It is the commitment to perpetual celibate chastity that distinguishes Religious or Secular Institutes from of groupings of Christians. Secular and Religious Institutes make vows or similar promises that are morally binding. They place themselves under the Superiors of these Institutes who have real authority over their members that are morally binding. The Code on Canon Law dealing with secular Institutes state that the profession of the counsels in a secular Institute may be made by vow, oath or another recognized expression of consecration. All members of secular institutes must make a binding profession by vow or oath to celibate chastity and make vows or binding promises of poverty and obedience. While not trying to appear excessively juridical it is important to understand that profession in a secular institute entails a full, total and complete consecration of self no less than in vowed Religious life. -

For a Better Understanding of Lasallian Association.” AXIS: Journal of Lasallian Higher Education 5, No

Sauvage, Michel. “For a Better Understanding of Lasallian Association.” AXIS: Journal of Lasallian Higher Education 5, no. 2 (Institute for Lasallian Studies at Saint Mary’s University of Minnesota: 2014). © Institute of the Brothers of the Christian Schools. Readers of this article have the copyright owner’s permission to reproduce it for educational, not-for-profit purposes, if the author and publisher are acknowledged in the copy. For a Better Understanding of Lasallian Association Michel Sauvage, FSC, S.T.D.1 I have been asked to introduce this formation session on Lasallian association. To do that, I must first recall what association meant at the beginning of the Institute of the Brothers of the Christian Schools. As a foreword to this talk, I would make three points on the parameters of my proposal with regard to the aim of these two days. For you, who are heads of establishments and responsible for educational institutions under a Lasallian trusteeship, this aim is to live out association better today. So, my first point is that I will stick to the meaning of the word association and the realities that it had in the founding experience of John Baptist de La Salle and his first Brothers. I will thus at least go some way to addressing the sub-titles given in the program: History, Origins, Characteristics. It is not possible, however, even to sketch out a development that would relate to another subtitle: “Experiences ‘in the course of history.’” Since I have not studied this question, I am not even certain of fully understanding what it means. -

Childlike Simplicity and Our Lady in the Congregation of The

INSTITUTE OF SPIRITUALITY AND RELIGIOUS FORMATION TANGAZA COLLEGE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF EAST AFRICA TITLE OF THE LONG ESSAY CHILDLIKE SIMPLICITY AND OUR LADY IN THE CONGREGATION OF THE LITTLE CHILDREN OF OUR BLESSED LADY Author: Sr. Florence Muchingami (L.C.B.L) Tutor : Rev. Fr. Aelred Lacomara (CP) April 2001 NAIROBI - KENYA INSTITUTE OF SPIRITUALITY AND RELIGIOUS FORMATION TANGAZA COLLEGE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF EAST AFRICA TITLE OF THE LONG ESSAY CHILDLIKE SIMPLICITY AND OUR LADY IN THE CONGREGATION OF THE LITTLE CHILDREN OF OUR BLESSED LADY Author: Sr. Florence Muchingami (L.C.B.L) Tutor : Rev. Fr. Aelred Lacomara (CP) This is a long essay submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a diploma in Religious Formation April 2001 NAIROBI - KENYA 11 S.. STUDENT'S DECLARATION I hereby declare that the material used herein has not been submitted for academic credit to any other institution. All sources have been cited in full. Signed:tnnL-filktin:Intri Lca; Sr. Florence Muchingami L.C.B.L Date : Tutor : Rev. Fr. Aelred Lacomara (CP) Date : 111 DEDICATION I dedicate this work to my family, congregation and all the little ones who reveal God's presence and hold the secrets of the Kingdom. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am very grateful to all who have helped me along the journey towards the completion of this work. Many thanks go to my supervisor Father Aelred Lacomara (CP), without whose encouragements, patience and directives this paper could not have been realised. I also thank Fr. Peter Edmonds (SJ) for proof reading my work and his constructive ideas and suggestions. -

A M D G Beaumont Union Review Summer 2018

A M D G BEAUMONT UNION REVIEW SUMMER 2018 Those of you who attended the lunch at St John‘s on Remembrance Sunday last year may recall, that in my words of thanks to the Headmaster and Staff, I said that we talk of this nebulous concept of the ―Spirit of Beaumont‖. I continued: ―Yet we have the living embodiment of that Spirit right here‖. Up until 1967 St John‘s was always considered part of Beaumont and its Old boys whether they continued to the College or not eligible for The Union. That year they were cast adrift and I think the feeling of the Committee was that it was now the Stonyhurst prep in the south of England and it would have a new allegiance. 50 years on and this is no longer the case. They wear our colours, harbour our traditions, sing the Carmen. They play cricket on our grounds and honour the dead at the War Memorial. It is long overdue to rectify the situation and bring the BU and the SJBOBA into closer alignment (sounds Brexit). In 1905, younger members of the Union founded the Beaumont Casuals whose activities were more in keeping with their generation. It lasted four years when the Club came to an end, yet it was written that ―the idea of younger members associating together for sports and social gatherings is a good one, and it is hoped that one day the Casuals will come to life again‖. I think that time has come. ANNOUNCEMENTS MUSEUM In February I met with Giles Delaney at St John’s and I know you will all be pleased to hear that our memorabilia will, where possible, soon go on display. -

Claimfordignity. Nr. 5

Magazine No. 5 / February 2018 € 7,00 sfr 9,00 Africa & South America free 0 iISBN 978-3-9815663-0-7 claim for dignity. Report of the German Non-Governmental Organisation Claim for Dignity e.V. Year XVI ebook Human and Social Affairs - Religion, Art and Culture - Nature, Sustainability, Environment and Technology Believe in the Experience of Life 0 Cover Picture: Benilda [2011 - Image CfD] Networking Networking AFBW – South-West Germany’s Network for Fibre-Based Materials [73] The Baden-Württemberg Alliance for Fiber- The work of the AFBW makes it a key player in Based Materials (Allianz Faserbasierter the world of fibers, and beyond. A core focus is Werkstoffe Baden-Württemberg, AFBW) is a promoting the use of fiber-based materials in a multi-industry technology network. It encour- wide variety of applications, including smart ages exchange across the value chain for fi- textiles, architecture and construction, aero- bers – connecting manufacturers, users, and space and automotive engineering, environ- researchers. mental technology, medicine, and lightweight AFBW provides a platform for dialog and construction. knowledge transfer, and is a committed driver of innovation. In collaboration with its mem- bers and partners, AFBW identifies and pro- motes novel solutions, and supports the ‘re- naissance of fibers’. Added value through networking AFBW: provides early access to information and new markets enables networking, and helps people and organizations to connect provides knowledge and encourages knowledge transfer supports collaborative projects with the aim of putting pioneering ideas into practice pools expertise and encourages technology transfer – strengthening strengths connects members to multipliers, opinion leaders and networks AFBW promotes the development and use of Image AFBW fiber-based materials across multiple indus- tries, and provides fresh impetus for innova- tion. -

The Adrian Dominican Sisters in the Us and Dominican Republic, 1933-61

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ NOVICES, NUNS, AND COLEGIO GIRLS: THE ADRIAN DOMINICAN SISTERS IN THE U.S. AND DOMINICAN REPUBLIC, 1933-61. A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in HISTORY with an emphasis in FEMINIST STUDIES by Elizabeth Dilkes Mullins March 2014 The dissertation of Elizabeth Dilkes Mullins is approved: ___________________________ Professor Marilyn J. Westerkamp ___________________________ Professor Susan Harding ___________________________ Professor Emily Honig ___________________________ Professor Alice Yang ________________________________ Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Table of Contents Introduction: Novices, Nuns, and Colegio Girls. ...................................................... i Chapter 1: Adrian Dominican Sisters in Context: The Adrian Congregation and Pre-War Catholic America ...................................................................................... 23 Chapter 2: “In the world but not of it”: Adrian Dominican Sisters Negotiating Modernity Through Body, 1933-39 ........................................................................... 46 Chapter 3: “This is a peculiar place, Mother”: The Post WWII Dominican Republic and the Foundation of Colegio Santo Domingo. .................................... 85 Chapter 4: Colegio Girls – The Colegio’s Two Curriculums ............................. 129 Chapter 5: Body Politics ........................................................................................ -

S T . T H E R E S a P a R I

ST. THERESA CATHOLIC CHURCH SEPTEMBER 20, 2015 TWENTY-FIFTH SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME SS TT .. TTHERESAHERESA PP ARISHARISH A RCHDIOCESE OF G ALVESTON— H OUSTON ST. THERESA CATHOLIC CHURCH 705 ST. THERESA BOULEVARD SUGAR LAND, TX 77498 281-494-1156 WWW.SUGARLANDCATHOLIC.COM ST. THERESA CATHOLIC CHURCH SEPTEMBER 20, 2015 CONTENTS FAITH FORMATION - CCE Families can now register online. Just go to Pope Francis………………..…...…….………….….. 3 www.SugarLandCatholic.com The registration link is on the top of the main page. Ministerios en Español…….…..……….…...……….. 4 Papa Francisco…....……….…...….….…………...… 5 Avisos en Español……….. .…..……….…...……….. 6 News and Announcements………...………….…... 7 School/ Religious Ed/ CCE…………....……………… 8 Mass Intentions……………………………………… 9 Weekly Schedule of Events………………………... 9 Study Program: Priest, Prophet , King …......……… 10 We are always looking for volunteers! RCIA Q & A…….…………………………………….. 11 Call the CCE office for more details: 281-494-1156 Daily Scripture Readings……………...…..………… 12 O NLINE GIVING More Announcements………...……………………... 13 The parish website has instructions on how to register Parish contact information……………….............. 15 for convenient on-line giving. You will have full con- trol of your contribution account and scheduling. This option can be a great way to support your church and honor the Lord with your resources. If you would like www.SugarLandCatholic.com to begin online giving, either visit the link on our web- site or call Diane Senger 281-494-1156. www.SugarLandCatholic.com MASS AND CONFESSION SCHEDULE WEEKDAYS ENTRE SEMANA CONFESSION SATURDAY SÁBADO Monday—Friday Saturday Sábado 8:30 a.m. 6:45 a.m., 8:30 a.m. 3:15 p.m. – 4:15 p.m. 5:00 p.m. Anticipated Mass Sunday Domingo SUNDAY DOMINGO 4:00 p.m. -

An Introduction to Christian Mysticism Initiation Into the Monastic Tradition 3 Monastic Wisdom Series

monastic wisdom series: number thirteen Thomas Merton An Introduction to Christian Mysticism Initiation into the Monastic Tradition 3 monastic wisdom series Patrick Hart, ocso, General Editor Advisory Board Michael Casey, ocso Terrence Kardong, osb Lawrence S. Cunningham Kathleen Norris Bonnie Thurston Miriam Pollard, ocso MW1 Cassian and the Fathers: Initiation into the Monastic Tradition Thomas Merton, OCSO MW2 Secret of the Heart: Spiritual Being Jean-Marie Howe, OCSO MW3 Inside the Psalms: Reflections for Novices Maureen F. McCabe, OCSO MW4 Thomas Merton: Prophet of Renewal John Eudes Bamberger, OCSO MW5 Centered on Christ: A Guide to Monastic Profession Augustine Roberts, OCSO MW6 Passing from Self to God: A Cistercian Retreat Robert Thomas, OCSO MW7 Dom Gabriel Sortais: An Amazing Abbot in Turbulent Times Guy Oury, OSB MW8 A Monastic Vision for the 21st Century: Where Do We Go from Here? Patrick Hart, OCSO, editor MW9 Pre-Benedictine Monasticism: Initiation into the Monastic Tradition 2 Thomas Merton, OCSO MW10 Charles Dumont Monk-Poet: A Spiritual Biography Elizabeth Connor, OCSO MW11 The Way of Humility André Louf, OCSO MW12 Four Ways of Holiness for the Universal Church: Drawn from the Monastic Tradition Francis Kline, OCSO MW13 An Introduction to Christian Mysticism: Initiation into the Monastic Tradition 3 Thomas Merton, OCSO monastic wisdom series: number thirteen An Introduction to Christian Mysticism Initiation into the Monastic Tradition 3 by Thomas Merton Edited with an Introduction by Patrick F. O’Connell Preface by Lawrence S. Cunningham CISTERCIAN PUblications Kalamazoo, Michigan © The Merton Legacy Trust, 2008 All rights reserved Cistercian Publications Editorial Offices The Institute of Cistercian Studies Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan 49008-5415 [email protected] The work of Cistercian Publications is made possible in part by support from Western Michigan University to The Institute of Cistercian Studies. -

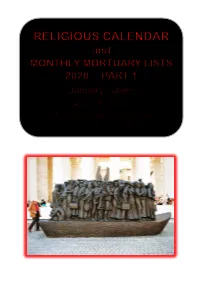

Marist Rel Calendar 2020 Part 1 .Pdf

On Sunday 29 September 2019, Pope Francis unveiled a monument to migration to mark the 105th World Day of Migrants and Refugees ANGELS UNAWARE by Canadian artist Timothy P. Schmalz depicts 140 migrants and refugees travelling on a boat and includes indigenous people, the Virgin Mary and Joseph, Jews fleeing Nazi Germany and those from war-torn lands. JANUARY RELIGIOUS CALENDAR 2020 LECTIONARY: Sundays - Cycle A Weekdays - Year 2 JANUARY 1. WEDNESDAY SOLEMNITY OF MARY, MOTHER OF GOD World Day of Peace POPE’S INTENTION: We pray that Christians, followers of other religions, and all people of goodwill may promote peace and justice in the world. MARIST HISTORY: 1818, Antoine Couturier, joined the La Valla community, becoming the fourth brother in the Institute. MORTUARY LIST: 1993 - Br Anacleti Kanyumbu, Malawi; 2006 - Br Abdon Nkhuwa, Zambia. BIRTHDAY: 1925 - Paul Nkhoma; 1986 - Sábado Valia 2. THURSDAY FOUNDATION DAY OF THE INSTITUTE (Suggested - “Marist Office”) Saints Basil the Great 379 and Gregory Nazianzen 390. Memorial Ps Week 1 MORTUARY LIST: All those in the list for January. MARIST HISTORY: 1817: On this day, Father Marcellin Champagnat took Jean-Marie Granjon and Jean-Baptiste Audras, two young men who had agreed to help him teach children, to live in the little house in Lavalla that became the “cradle” of the Institute. 1923 - Foundation in El Salvador. 2002 - The formal incorporation of the Sector of Angola into the Province of Southern Africa during a ceremony in Luanda. 3. FRIDAY Christmas Weekday 4. SATURDAY Christmas Weekday. 5. SUNDAY EPIPHANY OF THE LORD Solemnity MARIST HISTORY: 1970 - Foundation in Nicaragua.