The Art of Enrico Donati

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PAVIA, PHILIP, 1915-2005. Philip Pavia and Natalie Edgar Archive of Abstract Expressionist Art, 1913-2005

PAVIA, PHILIP, 1915-2005. Philip Pavia and Natalie Edgar archive of abstract expressionist art, 1913-2005 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Descriptive Summary Creator: Pavia, Philip, 1915-2005. Title: Philip Pavia and Natalie Edgar archive of abstract expressionist art, 1913-2005 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 981 Extent: 38 linear feet (68 boxes), 5 oversized papers boxes and 5 oversized papers folders (OP), 1 extra oversized papers folder (XOP) and AV Masters: 1 linear foot (1 box) Abstract: Philip Pavia and Natalie Edgar archive of abstract expressionist art including writings, photographs, legal records, correspondence, and records of It Is, the 8th Street Club, and the 23rd Street Workshop Club. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Unrestricted access. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction All requests subject to limitations noted in departmental policies on reproduction. Source Purchase, 2004. Additions purchased from Natalie Edgar, 2018. Citation [after identification of item(s)], Philip Pavia and Natalie Edgar archive of abstract expressionist art, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University. Processing Processed by Elizabeth Russey and Elizabeth Stice, October 2009. Additions added to the collection in 2018 retain the original order in which they were received. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. Copies supplied may not be copied for others or otherwise distributed without prior consent of the holding repository. Philip Pavia and Natalie Edgar archive of abstract expressionist art, Manuscript Collection No. -

Enrico Donati on Marcel Duchamp

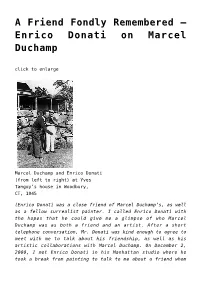

A Friend Fondly Remembered – Enrico Donati on Marcel Duchamp click to enlarge Marcel Duchamp and Enrico Donati (from left to right) at Yves Tanguy’s house in Woodbury, CT, 1945 (Enrico Donati was a close friend of Marcel Duchamp’s, as well as a fellow surrealist painter. I called Enrico Donati with the hopes that he could give me a glimpse of who Marcel Duchamp was as both a friend and an artist. After a short telephone conversation, Mr. Donati was kind enough to agree to meet with me to talk about his friendship, as well as his artistic collaborations with Marcel Duchamp. On December 2, 2000, I met Enrico Donati in his Manhattan studio where he took a break from painting to talk to me about a friend whom he fondly remembered.) 1942: Donati was sitting in the Larré Restaurant in New York City with about a dozen friends, when he saw a well-dressed gentleman approach the restaurant. The man came inside and headed towards their table as André Breton stood to greet him. To Donati’s surprise, Breton bowed to the man, expressing his reverence. Donati wondered who this great man must be that the founder of surrealism, or the “pope” as Donati calls him, would bow down at his feet. The gentleman soon satisfied Donati’s curiosity, saying “Call me Marcel. Who are you?” As Donati responded to his inquiry, simply by stating that he was “Enrico,” a great friendship began. This friendly discourse resulted in a life-long friendship that Donati fondly reflects upon. Their relationship was hardly dependent on their mutual love for art. -

Surrealism, Occultism and Politics

Surrealism, Occultism and Politics This volume examines the relationship between occultism and Surrealism, specif- ically exploring the reception and appropriation of occult thought, motifs, tropes and techniques by surrealist artists and writers in Europe and the Americas from the 1920s through the 1960s. Its central focus is the specific use of occultism as a site of political and social resistance, ideological contestation, subversion and revolution. Additional focus is placed on the ways occultism was implicated in surrealist dis- courses on identity, gender, sexuality, utopianism and radicalism. Dr. Tessel M. Bauduin is a Postdoctoral Research Associate and Lecturer at the Uni- versity of Amsterdam. Dr. Victoria Ferentinou is an Assistant Professor at the University of Ioannina. Dr. Daniel Zamani is an Assistant Curator at the Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main. Cover image: Leonora Carrington, Are you really Syrious?, 1953. Oil on three-ply. Collection of Miguel S. Escobedo. © 2017 Estate of Leonora Carrington, c/o Pictoright Amsterdam 2017. This page intentionally left blank Surrealism, Occultism and Politics In Search of the Marvellous Edited by Tessel M. Bauduin, Victoria Ferentinou and Daniel Zamani First published 2018 by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 and by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2018 Taylor & Francis The right of Tessel M. Bauduin, Victoria Ferentinou and Daniel Zamani to be identified as the authors of the editorial material, and of the authors for their individual chapters, has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

Oral History Interview with Enrico Donati, 1968 September 9

Oral history interview with Enrico Donati, 1968 September 9 Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Enrico Donati on September 9, 1968. The interview was conducted in the artist's studio in New York City by Forest Selvig for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Interview FS: FORREST SELVIG ED: ENRICO DONATI FS: This is the first tape of an interview with Enrico Donati in his New York studio on Monday, the 9th of September, 1968. The interviewer is Forrest Selvig. We're sitting in Mr. Donati's studio overlooking Central Park. Now we can just converse as though this tape somehow doesn't exist. Mr. Donati, you told me that you came here for the first time when you were 27. ED: No. I came in 1934. I was 25. And I spent three months visiting the country, particularly I came because I was interested in Indian art. So when I landed in New York by boat naturally I went directly to New Mexico and Arizona. And I started to visit the different Indian villages and tried to get acquainted with their ways of living, their habits, their art, their tools. I spent about a month with them. And I collected already at that time . I exchanged all sorts of gadgets that I had brought from Europe to try to collect some Hopi Indian cachina dolls and other Indian objects. -

Listed Exhibitions (PDF)

G A G O S I A N G A L L E R Y Arshile Gorky Biography 1902 - 1948 Solo Gallery Exhibitions: 2011 *Arshile Gorky: 1947. Gagosian Gallery, New York. 2010 *Arshile Gorky: Virginia Summer 1946. Gagosian Gallery, London. 2006 Arshile Gorky: Early Drawings. CDS Gallery, New York. 2004 *Arshile Gorky: The Early Years. Jack Rutberg Fine Arts, Los Angeles. 2002 *Arshile Gorky. Galerie 1900-2000, Paris. *Arshile Gorky: Portraits. Gagosian Gallery, New York. 1998 *Arshile Gorky: Paintings and Drawings, 1929-1942 (through 1999). 1997 Arshile Gorky: Two Decades. Meyerson & Nowinski Art Associates, Seattle, WA. Arshile Gorky: Drawings. Manny Silverman Gallery, Los Angeles. 1994 *Arshile Gorky: Late Drawings. Marc de Montebello Fine Art, Inc., New York. *Arshile Gorky: Late Paintings. Gagosian Gallery, New York. 1993 *Arshile Gorky. Galerie Marwan Hoss, Paris. 1991 *Arshile Gorky: Drawings. Louis Newman Galleries, Beverly Hills, CA. 1990 *Arshile Gorky: Three Decades of Drawings. Gerald Peters Gallery, Santa Fe, NM; Gerald Peters Gallery, Dallas, TX; Gerald Peters Gallery, New York; Butler Institute of American Art, Youngstown, OH. 1979 *Arshile Gorky: Important Paintings and Drawings. Xavier Fourcade, Inc., New York. 1978 *Arshile Gorky, In Memory. Washburn Gallery, New York. 1975 Arshile Gorky: Works on Paper. M. Knoedler & Co., New York. 1973 Arshile Gorky: Drawings and Paintings from 1931-1946. Ruth Schaffner Gallery, Santa Barbara, CA. 1972 Arshile Gorky: Paintings and Drawings. Allan Stone Gallery, New York. *Arshile Gorky, 1904-1948. Dunkelman Gallery, Toronto. *Arshile Gorky. Galleria Galatea, Turin. 1971 ArshileGorky: Zeichnungen und Bilder aus der Collection von Julien Levy. Galerie Brusberg, Hannover. 1970 Arshile Gorky Drawings. -

Guggenheim Museum Archives Reel-To-Reel Collection Antoni Tàpies with Lawrence Alloway

Guggenheim Museum Archives Reel-to-Reel collection Antoni Tàpies with Lawrence Alloway THOMAS M. MESSER Ladies and gentlemen, can you hear me? Let me welcome you and congratulate you to your courage to brave the weather and to come in on a cold day like this. I shall take a minute for a few announcements which have to do with the resumption of our staff lecture program during weekdays. Beginning with February 15th, we shall have a regular Thursday and Friday lecture at 4:00 in the afternoon given by members of the staff. Mr. Daniel Robbins, our assistant curator, and Dr. Louise Svendsen, our curator of education, will hold alternate lectures [01:00] on Thursday. And a new member of our staff, Mr. Maurice Tuchman, will be Friday lecturer. This afternoon staff lecture program, which is oriented toward the public in general, and which deals with broader subjects not necessarily connected with the exhibition program, will be reinforced by our vice president, Mr. Anderson, who will also join this group. The Sunday lectures, of course, will continue. But we shall take a brief break between the lecture today and the next one, skip from the usual two weeks to a four-weeks pause, and resume again on March 11th when I’ll have the privilege of starting a lecture sequence which will [02:00] address itself to problems of cubism and in particular to Fernand Leger, whose exhibition is scheduled to start at the museum on February 28th. My lecture on Sunday, March 11th, will be followed in two-weeks intervals by lectures given on the same subject, on Leger and cubism. -

Exhibition History 1919-1998

Exhibitions at The Phillips Collection, 1919-1998 [Excerpted from: Passantino, Erika D. and David W. Scott, eds. The Eye of Duncan Phillips: a collection in the making. Washington D.C.: The Phillips Collection, 1999.] This document includes names and dates of exhibitions created by and/or shown at The Phillips Collection. Most entries also include the number of works in each show and brief description of related published materials. 1919 DP.1919.1* "A Group of Paintings From the Collection of our Fellow Member Duncan Phillips. Century, New York. May 18-June 5. 30 works. Partially reconstructed chklst. 1920 DP.1920.1* "Exhibition of Selected Paintings from the Collections of Mrs. D. C. Phillips and Mr. Duncan Phillips of Washington." Corcoran, Washington, D.C. Mar. 3-31. 62 works. Cat. DP.1920.2* "A Loan Exhibition from the Duncan Phillips Collection." Knoedler, New York. Summer. 36 works. Chklst. PMAG.1920.3* "Selected Paintings from the Phillips Memorial Art Gallery." Century, New York. Nov. 20, 1920-Jan. 5, 1921. 43 works (enlarged to 45 by Dec. 20). Cat. 1921 Phillips organized no exhibitions in 1921, spending most of his time preparing for the opening of his gallery. He showed his collection by scheduled appointment only. 1922 PMAG.1922. [Opening Exhibition]. Main Gallery. Feb. 1-opening June 1, 1922. Partially reconstructed chklst. PMAG.1922.1* "Exhibition of Oil Paintings by American Artists Loaned by the Phillips Memorial Art Gallery, Washington, D.C." L.D.M. Sweat Memorial Art Museum, Portland, Maine. Feb. 4-15. 22 works. Cat. PMAG.1922.2 "Second Exhibition of the Phillips Memorial Art Gallery." Main Gallery. -

Jean-Noel Archive.Qxp.Qxp

THE JEAN-NOËL HERLIN ARCHIVE PROJECT Jean-Noël Herlin New York City 2005 Table of Contents Introduction i Individual artists and performers, collaborators, and groups 1 Individual artists and performers, collaborators, and groups. Selections A-D 77 Group events and clippings by title 109 Group events without title / Organizations 129 Periodicals 149 Introduction In the context of my activity as an antiquarian bookseller I began in 1973 to acquire exhibition invitations/announcements and poster/mailers on painting, sculpture, drawing and prints, performance, and video. I was motivated by the quasi-neglect in which these ephemeral primary sources in art history were held by American commercial channels, and the project to create a database towards the bibliographic recording of largely ignored material. Documentary value and thinness were my only criteria of inclusion. Sources of material were random. Material was acquired as funds could be diverted from my bookshop. With the rapid increase in number and diversity of sources, my initial concept evolved from a documentary to a study archive project on international visual and performing arts, reflecting the appearance of new media and art making/producing practices, globalization, the blurring of lines between high and low, and the challenges to originality and quality as authoritative criteria of classification and appreciation. In addition to painting, sculpture, drawing and prints, performance and video, the Jean-Noël Herlin Archive Project includes material on architecture, design, caricature, comics, animation, mail art, music, dance, theater, photography, film, textiles and the arts of fire. It also contains material on galleries, collectors, museums, foundations, alternative spaces, and clubs. -

ITALIAN MODERN ART | ISSUE 3: ISSN 2640-8511 Introduction

ITALIAN MODERN ART | ISSUE 3: ISSN 2640-8511 Introduction ITALIAN MODERN ART - ISSUE 3 | INTRODUCTION italianmodernart.org/journal/articles/introduction-3 Raffaele Bedarida | Silvia Bignami | Davide Colombo Methodologies of Exchange: MoMA’s “Twentieth-Century Italian Art” (1949), Issue 3, January 2020 https://www.italianmodernart.org/journal/issues/methodologies-of- exchange-momas-twentieth-century-italian-art-1949/ ABSTRACT A brief overview of the third issue of Italian Modern Art dedicated to the MoMA 1949 exhibition Twentieth-Century Italian Art, including a literature review, methodological framework, and acknowledgments. If the study of artistic exchange across national boundaries has grown exponentially over the past decade as art historians have interrogated historical patterns, cultural dynamics, and the historical consequences of globalization, within such study the exchange between Italy and the United States in the twentieth-century has emerged as an exemplary case.1 A major reason for this is the history of significant migration from the former to the latter, contributing to the establishment of transatlantic networks and avenues for cultural exchange. Waves of migration due to economic necessity in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries gave way to the smaller in size but culturally impactful arrival in the U.S. of exiled Jews and political dissidents who left Fascist Italy during Benito Mussolini’s regime. In reverse, the presence in Italy of Americans – often participants in the Grand Tour or, in the 1950s, the so-called “Roman Holiday” phenomenon – helped to making Italian art, past and present, an important component in the formation of American artists and intellectuals.2 This history of exchange between Italy and the U.S. -

How Native Alaskan Culture in Uenced Surrealist Masters

(http://www.galeriemagazine.com) (http://www.galeriemagazine.com/wp- NEWSLETTER content/uploads/2018/02/Spring- Sign up to receive the best in art, design, and culture 2018-cover_Web.jpg) from Galerie Enter email SUBSCRIBE (HTTPS://WWW.PUBSERVICE.COM/S0/DEFAULT.ASPX?PC=GA&PK) ART + CULTURE (HTTP://WWW.GALERIEMAGAZINE.COM/CATEGORY/ART/) INTERIORS (HTTP://WWW.GALERIEMAGAZINE.COM/CATEGORY/HOME-ARCHITECTURE/) PEOPLE (HT (http://www.galeriemagazine.com/how-the-native-americans-from-alaska-in�uenced-surrealist-art/) Publication: Galerie Magazine (http://www.galeriemagazine.com) Date: May 3, 2018 (http://www.galeriemagazine.com) Author: Margaret Carrigan (http://www.galeriemagazine.com/wp- NEWSLETTER (http://www.galeriemagazine.com/wp- content/uploads/2018/02/Spring- Sign up to receive the best in art, design, and culture 2018-cover_Web.jpg) from Galerie NEWSLETTER Enter email content/uploads/2018/02/Spring- SUBSCRIBE (HTTPS://WWW.PUBSERVICE.COM/S0/DEFAULT.ASPX?PC=GA&PK) ART + CULTURE (HTTP://WWW.GALERIEMAGAZINE.COM/CATEGORY/ART/) INTERIORS (HTTP://WWW.GALERIEMAGAZINE.COM/CATEGORY/HOME-ARCHITECTURE/) PSEOigPLnE u(HpT to receive the best (http://www.galeriemagazine.com/how-the-native-americans-from-alaska-in�uenced-surrealist-art/) in art, design, and culture 2H018-coovewr_We bN.jpg) ative Alaskan Culture from Galerie Enter email ISnUBSC�RIBE (uHTTPSe://WnWW.PcUBSEeRVICEd.COM/ S0S/DEFuAULT.ArSPXr?PCe=GA&aPK) lisART t + C UMLTURE (HaTTP:/s/WWtW.eGALERrIEMsAGAZINE.COM/CATEGORY/ART/) INTERIORS (HTTP://WWW.GALERIEMAGAZINE.COM/CATEGORY/HOME-ARCHITECTURE/) PEOPLE (HT (http://www.galeriemagazine.com/how-the-native-americans-from-alaska-in�uenced-surrealist-art/) A fascinating exhibition at New York’s Di Donna Galleries sheds light on a long overlooked cultural exchange Joan Miró, Personnage dans la nuit, 1944. -

Abstract Expressionism 1 Abstract Expressionism

Abstract expressionism 1 Abstract expressionism Abstract expressionism was an American post–World War II art movement. It was the first specifically American movement to achieve worldwide influence and put New York City at the center of the western art world, a role formerly filled by Paris. Although the term "abstract expressionism" was first applied to American art in 1946 by the art critic Robert Coates, it had been first used in Germany in 1919 in the magazine Der Sturm, regarding German Expressionism. In the USA, Alfred Barr was the first to use this term in 1929 in relation to works by Wassily Kandinsky.[1] The movement's name is derived from the combination of the emotional intensity and self-denial of the German Expressionists with the anti-figurative aesthetic of the European abstract schools such as Futurism, the Bauhaus and Synthetic Cubism. Additionally, it has an image of being rebellious, anarchic, highly idiosyncratic and, some feel, nihilistic.[2] Jackson Pollock, No. 5, 1948, oil on fiberboard, 244 x 122 cm. (96 x 48 in.), private collection. Style Technically, an important predecessor is surrealism, with its emphasis on spontaneous, automatic or subconscious creation. Jackson Pollock's dripping paint onto a canvas laid on the floor is a technique that has its roots in the work of André Masson, Max Ernst and David Alfaro Siqueiros. Another important early manifestation of what came to be abstract expressionism is the work of American Northwest artist Mark Tobey, especially his "white writing" canvases, which, though generally not large in scale, anticipate the "all-over" look of Pollock's drip paintings. -

Contemporary American Painting and Sculpture

^^" J LIBRA R.Y OF THt U N I VER5ITY or ILLINOIS 759.1 1950 cop.3 i'T ^ el --^» lAiiirirnH NOTICE: Return or renew all Library Materialsl The Minimum Fee for each Lost Book is $50.00. The person charging this material is responsible for its return to the library from which it was withdrawn on or before the Latest Date stamped below. Theft, mutilation, and underlining of books are reasons for discipli- nary action and may result in dismissal from the University. To renew call Telephone Center, 333-8400 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN ^/iy ^^CH, ''recr.% L161—O-1096 ''::*mHlf. «t.«t- ARCrirk'C'lOKE t\^ff. I'KiURE AND MASK Abraham Rattiicr UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS EXHIBITION OF CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN PAINTING College of Fine and Applied Arts Urbana, Illinois Architecture Building .,£ ,^,^ ^,jv^_y pp Sunday, February 26 throueh Sunday, April 2, 1950 FES'- 7 1950 l)N!VFR';iT-f or I' MNCIS UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS EXHIBITION OF CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN PAINTING GEORGE D. STODDARD President of the University DEAN REXFORD NEWCOMB Chairman, Festival of Contemporary Arts OPERATING COMMITTEE N. Britsky M, B. Martin C. A. Dietemann M. A. Sprague C. V. Donovan A. S. Weller, Chairman I D. Hogan J. \ STAFF COMMITTEE MEMBERS L. F. Bailey R. Perlman J. Betts A. J. Pulos C. E. Bradbury E. C. Rae C. W. Briggs J. W. Raushenberger W. F. Doolittle F. J. Roos R. L. Drummond H. A. Schultz R. E. Eckerstrom J. R. Shipley G. N. Foster B. R. Stepner R. E. Hult L. M. Woodroofe J.