Oral History Interview with Enrico Donati, 1968 September 9

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2 0 0 Jt COPYRIGHT This Is a Thesis Accepted for a Higher Degree of the University of London

REFERENCE ONLY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON THESIS Degree Year Name of Author 2 0 0 jT COPYRIGHT This is a thesis accepted for a Higher Degree of the University of London. It is an unpublished typescript and the copyright is held by the author. All persons consulting the thesis must read and abide by the Copyright Declaration below. COPYRIGHT DECLARATION I recognise that the copyright of the above-described thesis rests with the author and that no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. LOAN Theses may not be lent to individuals, but the University Library may lend a copy to approved libraries within the United Kingdom, for consultation solely on the premises of those libraries. Application should be made to: The Theses Section, University of London Library, Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU. REPRODUCTION University of London theses may not be reproduced without explicit written permission from the University of London Library. Enquiries should be addressed to the Theses Section of the Library. Regulations concerning reproduction vary according to the date of acceptance of the thesis and are listed below as guidelines. A. Before 1962. Permission granted only upon the prior written consent of the author. (The University Library will provide addresses where possible). B. 1962- 1974. In many cases the author has agreed to permit copying upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. C. 1975 - 1988. Most theses may be copied upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. D. 1989 onwards. Most theses may be copied. This thesis comes within category D. -

Not for the Uncommitted: the Alliance of Figurative Artists, 1969–1975 By

Not for the Uncommitted: The Alliance of Figurative Artists, 1969–1975 By Emily D. Markert Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Curatorial Practice California College of the Arts April 22, 2021 Not for the Uncommitted: The Alliance of Figurative Artists, 1969–1975 Emily Markert California College of the Arts 2021 From 1969 through the early 1980s, hundreds of working artists gathered on Manhattan’s Lower East Side every Friday at meetings of the Alliance of Figurative Artists. The art historical canon overlooks figurative art from this period by focusing on a linear progression of modernism towards medium specificity. However, figurative painters persisted on the periphery of the New York art world. The size and scope of the Alliance and the interests of the artists involved expose the popular narrative of these generative decades in American art history to be a partial one promulgated by a few powerful art critics and curators. This exploration of the early years of the Alliance is divided into three parts: examining the group’s structure and the varied yet cohesive interests of eleven key artists; situating the Alliance within the contemporary New York arts landscape; and highlighting the contributions women artists made to the Alliance. Keywords: Post-war American art, figurative painting, realism, artist-run galleries, exhibitions history, feminist art history, second-wave feminism Acknowledgments and Dedication I would foremost like to thank the members of my thesis committee for their support and guidance. I am grateful to Jez Flores-García, my thesis advisor, for encouraging rigorous and thoughtful research and for always making time to discuss my ideas and questions. -

The Gulf Stream

The Gulf Stream During those long war years, the cafeteria was our hangout evenings and nights. Sometimes though, we would just adjourn for a walk. Our walks would follow closely an itinerary of favorite streets. We started and ended always at the cafeteria. First we would walk east on Eighth Street passing the Hofmann School. On the corner of Eighth and Macdougal was the Jumble Shop restaurant. It was most active at lunchtime with art people from the Whitney Museum, which was in the middle of Eighth Street. [The building is now occupied by the New York Studio School.] The Whitney was an art group somewhat detached from us. Through the large windows of the Jumble Shop we would see on some evenings the cubist painter Stuart Davis talking away and Arshile Gorky waving his arms and stroking his long mustache. With them, especially when they were at the bar, were important-looking people. Maybe collectors. Very often they were Gorky’s own coterie—Raoul Hague, the sculptor, and Emanuel Navaretta, the poet. In later years, Emanuel and his wife Cynthia hosted a weekly open house for poets and writers, where Gorky was a regular. Or taking a left on Fifth Avenue to Fourteenth Street, then right on University Place and back to the park and Washington Square Arch, and across to Sullivan and MacDougal Streets, and another block further down on MacDougal Street we would go to the San Remo restaurant. Around this area in little Italy were various cafés and restaurants. Wandering here and there and stopping now and then, we zigzagged Sullivan and Thompson Streets, crossing and re-crossing. -

Postwar Abstraction in the Hamptons August 4 - September 23, 2018 Opening Reception: Saturday, August 4, 5-8Pm 4 Newtown Lane East Hampton, New York 11937

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Montauk Highway II: Postwar Abstraction in the Hamptons August 4 - September 23, 2018 Opening Reception: Saturday, August 4, 5-8pm 4 Newtown Lane East Hampton, New York 11937 Panel Discussion: Saturday, August 11th, 4 PM with Barbara Rose, Lana Jokel, and Gail Levin; moderated by Jennifer Samet Mary Abbott | Stephen Antonakos | Lee Bontecou | James Brooks | Nicolas Carone | Giorgio Cavallon Elaine de Kooning | Willem de Kooning | Fridel Dzubas | Herbert Ferber | Al Held | Perle Fine Paul Jenkins | Howard Kanovitz | Lee Krasner | Ibram Lassaw | Michael Lekakis | Conrad Marca-Relli Peter Moore |Robert Motherwell | Costantino Nivola | Alfonso Ossorio | Ray Parker | Philip Pavia Milton Resnick | James Rosati | Miriam Schapiro | Alan Shields | David Slivka | Saul Steinberg Jack Tworkov | Tony Vaccaro | Esteban Vicente | Wilfrid Zogbaum EAST HAMPTON, NY: Eric Firestone Gallery is pleased to announce the exhibition Montauk Highway II: Postwar Abstraction in the Hamptons, opening August 4th, and on view through September 23, 2018. In the 1950s and 1960s, the Hamptons became one of the most significant meeting grounds of like-minded artists, who gathered on the beach, in local bars, and at the artist-run Signa Gallery in East Hampton (active from 1957-60). It was an extension of the vanguard artistic activity happening in New York City around abstraction, which constituted a radical re-definition of art. But the East End was also a place where artists were freer to experiment. For the second time, Eric Firestone Gallery pays homage to this rich Lee Krasner, Present Conditional, 1976 collage on canvas, 72 x 108 inches and layered history in Montauk Highway II. -

PAVIA, PHILIP, 1915-2005. Philip Pavia and Natalie Edgar Archive of Abstract Expressionist Art, 1913-2005

PAVIA, PHILIP, 1915-2005. Philip Pavia and Natalie Edgar archive of abstract expressionist art, 1913-2005 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Descriptive Summary Creator: Pavia, Philip, 1915-2005. Title: Philip Pavia and Natalie Edgar archive of abstract expressionist art, 1913-2005 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 981 Extent: 38 linear feet (68 boxes), 5 oversized papers boxes and 5 oversized papers folders (OP), 1 extra oversized papers folder (XOP) and AV Masters: 1 linear foot (1 box) Abstract: Philip Pavia and Natalie Edgar archive of abstract expressionist art including writings, photographs, legal records, correspondence, and records of It Is, the 8th Street Club, and the 23rd Street Workshop Club. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Unrestricted access. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction All requests subject to limitations noted in departmental policies on reproduction. Source Purchase, 2004. Additions purchased from Natalie Edgar, 2018. Citation [after identification of item(s)], Philip Pavia and Natalie Edgar archive of abstract expressionist art, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University. Processing Processed by Elizabeth Russey and Elizabeth Stice, October 2009. Additions added to the collection in 2018 retain the original order in which they were received. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. Copies supplied may not be copied for others or otherwise distributed without prior consent of the holding repository. Philip Pavia and Natalie Edgar archive of abstract expressionist art, Manuscript Collection No. -

Enrico Donati on Marcel Duchamp

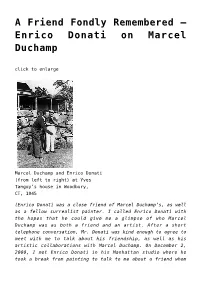

A Friend Fondly Remembered – Enrico Donati on Marcel Duchamp click to enlarge Marcel Duchamp and Enrico Donati (from left to right) at Yves Tanguy’s house in Woodbury, CT, 1945 (Enrico Donati was a close friend of Marcel Duchamp’s, as well as a fellow surrealist painter. I called Enrico Donati with the hopes that he could give me a glimpse of who Marcel Duchamp was as both a friend and an artist. After a short telephone conversation, Mr. Donati was kind enough to agree to meet with me to talk about his friendship, as well as his artistic collaborations with Marcel Duchamp. On December 2, 2000, I met Enrico Donati in his Manhattan studio where he took a break from painting to talk to me about a friend whom he fondly remembered.) 1942: Donati was sitting in the Larré Restaurant in New York City with about a dozen friends, when he saw a well-dressed gentleman approach the restaurant. The man came inside and headed towards their table as André Breton stood to greet him. To Donati’s surprise, Breton bowed to the man, expressing his reverence. Donati wondered who this great man must be that the founder of surrealism, or the “pope” as Donati calls him, would bow down at his feet. The gentleman soon satisfied Donati’s curiosity, saying “Call me Marcel. Who are you?” As Donati responded to his inquiry, simply by stating that he was “Enrico,” a great friendship began. This friendly discourse resulted in a life-long friendship that Donati fondly reflects upon. Their relationship was hardly dependent on their mutual love for art. -

Yayoi Kusama: Biography and Cultural Confrontation, 1945–1969

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects CUNY Graduate Center 2012 Yayoi Kusama: Biography and Cultural Confrontation, 1945–1969 Midori Yamamura The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/4328 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] YAYOI KUSAMA: BIOGRAPHY AND CULTURAL CONFRONTATION, 1945-1969 by MIDORI YAMAMURA A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2012 ©2012 MIDORI YAMAMURA All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Art History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Anna C. Chave Date Chair of Examining Committee Kevin Murphy Date Executive Officer Mona Hadler Claire Bishop Julie Nelson Davis Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract YAYOI KUSAMA: BIOGRAPHY AND CULTURAL CONFRONTATION, 1945-1969 by Midori Yamamura Adviser: Professor Anna C. Chave Yayoi Kusama (b.1929) was among the first Japanese artists to rise to international prominence after World War II. She emerged when wartime modern nation-state formations and national identity in the former Axis Alliance countries quickly lost ground to U.S.-led Allied control, enforcing a U.S.-centered model of democracy and capitalism. -

Surrealism, Occultism and Politics

Surrealism, Occultism and Politics This volume examines the relationship between occultism and Surrealism, specif- ically exploring the reception and appropriation of occult thought, motifs, tropes and techniques by surrealist artists and writers in Europe and the Americas from the 1920s through the 1960s. Its central focus is the specific use of occultism as a site of political and social resistance, ideological contestation, subversion and revolution. Additional focus is placed on the ways occultism was implicated in surrealist dis- courses on identity, gender, sexuality, utopianism and radicalism. Dr. Tessel M. Bauduin is a Postdoctoral Research Associate and Lecturer at the Uni- versity of Amsterdam. Dr. Victoria Ferentinou is an Assistant Professor at the University of Ioannina. Dr. Daniel Zamani is an Assistant Curator at the Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main. Cover image: Leonora Carrington, Are you really Syrious?, 1953. Oil on three-ply. Collection of Miguel S. Escobedo. © 2017 Estate of Leonora Carrington, c/o Pictoright Amsterdam 2017. This page intentionally left blank Surrealism, Occultism and Politics In Search of the Marvellous Edited by Tessel M. Bauduin, Victoria Ferentinou and Daniel Zamani First published 2018 by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 and by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2018 Taylor & Francis The right of Tessel M. Bauduin, Victoria Ferentinou and Daniel Zamani to be identified as the authors of the editorial material, and of the authors for their individual chapters, has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

The Waldorf Panels on Sculpture

THE WALDORF PANELS ON SCULPTURE (1965) NOTES ON USAGE In order to preserve the integrity of the stylistic emphasis placed upon particular movements and phrasings in the original, the capitalization from IT IS #6 is retained here. For the same reason, Phillip Pavia’s original hyphenation of the “Eighth-Street-Club” is also left unchanged. A t the end of Panel 1, several references are made to Marcel Duchamp’s “Urinal”; this is left as is, although the proper title of the work is Fountain (1917). Copyright © 2011 by Soberscove Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form, except for the inclusion of brief quotations and images in review, without prior permission from the publisher or copyright holders. The Waldorf Panel Transcripts (1 + 2) are reprinted here with the permission of Natalie Edgar. Photographs by John McMahon. Philip Pavia Papers, Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library (MARBL), Emory University. Access provided by MARBL. Used with the permission of Natalie Edgar. Selected unpublished excerpts from Waldorf Panel 2, Philip Pavia Papers, Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library (MARBL), Emory University. Access provided by MARBL. Used with the permission of Natalie Edgar. Soberscove Press is grateful to the following individuals for their helpful discussion and assistance in bringing this project to completion: Elizabeth Chase and Kathleen Shoemaker at MARBL, Michael Brenson, Rita Lascaro, Kristi McGuire, and Richard Squibbs. Soberscove especially wishes to thank both Natalie Edgar and Barbara McMahon for their generosity and interest in this project. Without Natalie Edgar’s support, this reprint would not have been possible. -

Listed Exhibitions (PDF)

G A G O S I A N G A L L E R Y Arshile Gorky Biography 1902 - 1948 Solo Gallery Exhibitions: 2011 *Arshile Gorky: 1947. Gagosian Gallery, New York. 2010 *Arshile Gorky: Virginia Summer 1946. Gagosian Gallery, London. 2006 Arshile Gorky: Early Drawings. CDS Gallery, New York. 2004 *Arshile Gorky: The Early Years. Jack Rutberg Fine Arts, Los Angeles. 2002 *Arshile Gorky. Galerie 1900-2000, Paris. *Arshile Gorky: Portraits. Gagosian Gallery, New York. 1998 *Arshile Gorky: Paintings and Drawings, 1929-1942 (through 1999). 1997 Arshile Gorky: Two Decades. Meyerson & Nowinski Art Associates, Seattle, WA. Arshile Gorky: Drawings. Manny Silverman Gallery, Los Angeles. 1994 *Arshile Gorky: Late Drawings. Marc de Montebello Fine Art, Inc., New York. *Arshile Gorky: Late Paintings. Gagosian Gallery, New York. 1993 *Arshile Gorky. Galerie Marwan Hoss, Paris. 1991 *Arshile Gorky: Drawings. Louis Newman Galleries, Beverly Hills, CA. 1990 *Arshile Gorky: Three Decades of Drawings. Gerald Peters Gallery, Santa Fe, NM; Gerald Peters Gallery, Dallas, TX; Gerald Peters Gallery, New York; Butler Institute of American Art, Youngstown, OH. 1979 *Arshile Gorky: Important Paintings and Drawings. Xavier Fourcade, Inc., New York. 1978 *Arshile Gorky, In Memory. Washburn Gallery, New York. 1975 Arshile Gorky: Works on Paper. M. Knoedler & Co., New York. 1973 Arshile Gorky: Drawings and Paintings from 1931-1946. Ruth Schaffner Gallery, Santa Barbara, CA. 1972 Arshile Gorky: Paintings and Drawings. Allan Stone Gallery, New York. *Arshile Gorky, 1904-1948. Dunkelman Gallery, Toronto. *Arshile Gorky. Galleria Galatea, Turin. 1971 ArshileGorky: Zeichnungen und Bilder aus der Collection von Julien Levy. Galerie Brusberg, Hannover. 1970 Arshile Gorky Drawings. -

A Finding Aid to the Robert Richenburg Papers, Circa 1910S-2008, Bulk 1950-2006, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Robert Richenburg Papers, circa 1910s-2008, bulk 1950-2006, in the Archives of American Art Catherine S. Gaines April 07, 2009 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical Note............................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Content Note................................................................................................. 3 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 4 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 5 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 6 Series 1: Biographical Material, circa 1910s-2006................................................... 6 Series 2: Correspondence, 1940-2007.................................................................... 8 Series 3: Subject Files, 1942-2008.......................................................................... 9 Series 4: Writings, circa -

Harriette Joffe

HARRIETTE JOFFE HARRIETTE JOFFE DAVENPORT AND SHAPIRO FINE ART Ocean, 1974. Oil on canvas, 72 x 72 in. Foreword Harriette Joffe: An American Painter By Michael McDonough Harriette Joffe is a bit of an enigma. Harriette Joffe is, in the end, an American artist of this new century and the last. Her touchstone Her body of work is simultaneously elusive and was the East End of Long Island during the coherent, formed initially during the 1960s and formative years of 20th-century American Art. still evolving today. She has conquered a wide Less introspective than the European-born First range of techniques—from color field to Generation Abstract Expressionists who she encaustic wax— employing them to relentlessly knew and worked with, her coming of age after explore the fissures between abstraction and World War II allowed her work an exuberance figuration, figuration and landscape: a that betrays her New World roots. Beyond that figurative painter with Abstract Expressionist fact, no one owns her. roots, perhaps. After New York, she traveled extensively in the But also: a feminist who had no truck with restless way of those born in the American conventional feminism—a post-feminist, Century: adventure under a beneficent Pax perhaps, 50 years before the word was coined; Americana. In New York she had rooted in and A painter of horses and sensual women discovered iconoclasm and experimentation, rendered on complex fields of Hebraic text and performance and landscape. In Italy, France, Spanish Catholic icons intertwined; and on the Iberian Peninsula she found the A watercolorist reworking dried surfaces with stubborn relevance of work done centuries ago.